In response to:

Can Congress Stop the President? from the April 19, 1973 issue

To the Editors:

I. F. Stone has given his usual captivating and comprehensive treatment to the war powers question in his article entitled “Can Congress Stop the President?” [NYR, April 19]. As should be obvious to those who read Mr. Stone’s piece, legislating a delineation of the war powers of Congress and the President is no easy task.

Some feel that to concede any unilateral war-making power whatsoever to the President is unacceptable. Others feel the same way about attempts to subjugate the President or interfere in any way with his current broad interpretation of the Commander-in-Chief clause of the Constitution. The War Powers Act, sponsored by Senators Javits, Stennis, and me, falls somewhere between these extremes, not because of a particular ideological bias, but because we tried as best we could to institutionalize the original intent of the Founders.

The records of the Constitutional Convention show that the Founders had a very restrictive view of the President’s right to conduct war without Congressional authorization. He would be able to “repel sudden attacks.” But the idea that he could somehow read that narrow delegation of power as authority to involve the United States in civil wars thousands of miles from our shores was completely alien to those who wrote the Constitution.

On these points Mr. Stone and I agree. We seem to go our separate ways, however, over the legislative formula by which we can return our system to its intended form.

The War Powers Act (S.440) describes three emergency conditions under which the President may use American Forces in the absence of Congressional authorization: 1) to repel an attack on the United States; 2) to repel an attack on American Forces; and 3) to protect while evacuating Americans endangered in foreign countries. The first two of these provisions are simply a reiteration of powers the President now possesses under the Commander-in-Chief clause. Legislation that attempted to interfere with that power would be clearly unconstitutional.

The third emergency provision—the evacuation of American citizens abroad—is, in effect, a statutory recognition of an historically accepted practice. While the practice was admittedly not considered at the Constitutional Convention, it has, over the years, been considered a reasonable delegation of Congress’s power. Problems have arisen, of course, when Presidents have expanded the rescue mission to encompass policy considerations far afield of the announced intention. We have carefully circumscribed the conditions of this delegated power in S. 440 by restricting the President to the rescue function.

Mr. Stone then takes issue with S. 440’s recognition of the President’s power to “forestall” an attack on the US or our Forces abroad. We have again simply reiterated what clearly is an extension of the President’s right to repel attacks. While the word “forestall” does permit a degree of discretion, it seems incongruous to recognize the President’s power to repel attacks and yet force him to wait until the first gun is fired before implementing adequate countermeasures. As Justice Storey pointed out in Martin v. Mott: “The power to provide for repelling invasions includes the power to provide against the attempt and danger of invasion as the necessary and proper means to effectuate the object.”

S. 440 carefully circumscribes the President’s discretion to “forestall” by placing the burden on him to prove that an attack is “direct and imminent.” If the President fails to demonstrate that his actions are in accordance with the provisions of our bill, his authority can be taken away by action of the Congress prior to thirty days, or, if Congress refuses to act, automatically, after thirty days.

I would also like to clarify my remarks before the House Foreign Affairs Committee concerning the 1965 Dominican Republic incident. As Mr. Stone correctly reported, I referred to President Johnson’s expansion of what he claimed to be a rescue operation as an “invasion”—hardly a word that would be used by one who supported the action. Mr. Stone has interpreted my statement that “the policy considerations that motivated President Johnson may have been correct” as a de facto endorsement of the action. I was, in reality, attempting to stress to a group of Congressmen (some of whom supported the 1965 action), that any policy consideration beyond the rescue action itself, is a matter for both Congress and the President to decide—not for the President to decide alone.

In addition, Mr. Stone alleges that the “doves” in the Senate split over the question of reinvolvement in Indochina and alleges that Senator Javits and I attempted to draw off support from the measure introduced by Senators Church and Case which attempts to force the President to seek. Congressional authorization for a reinvolvement of American forces in Indochina. This is an unfortunate distortion of the colloquy Senator Javits and I had on February 20.

After the January 27 signing of the Paris Agreement, numerous colleagues and members of the press had asked Senator Javits and me for an explanation of Section 9 of the War Powers Act. This section states that hostilities in which the United States is engaged as of the date of enactment will not be affected by the provisions of the bill.

The position that Senator Stennis took on Section 9, which he has since re-affirmed, was extremely important to our sixty cosponsors since he indicated that, even in the case of Indochina, the Senate should insist on its right to authorize a reinvolvement of American Forces (after the cease-fire).

Mr. Stone’s assertions that we were attempting to draw off support from Church-Case are therefore totally unfounded. I support the Church-Case amendment and deem that, under current conditions in Southeast Asia, its passage is imperative. I find nothing in Church-Case incompatible with the War Powers Act.

Thomas F. Eagleton

United States Senate

I.F Stone replies:

My article said that I found nothing incompatible between Church-Case and the War Powers Act and I am glad Senator Eagleton agrees. He made a strong statement supporting Church-Case just after we went to press, too late for inclusion in the article. I think Senators Eagleton, Javits, and Stennis performed a public service with S. 440 by precipitating a full debate on the question of war powers but I remain fearful of its thirty-day clause and still prefer the revised Zablocki Bill in the House. Though I must add—in justice to the senators—that the Zablocki Bill would not have been so improved without the stimulus of their measure. The first and most urgent task, as war widens in Cambodia, is to stop American intervention by passing the Church-Case bill as a rider to some other measure Nixon can hardly veto.

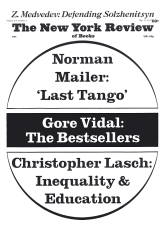

This Issue

May 17, 1973