In response to:

Getting Solzhenitsyn Straight from the May 17, 1973 issue

To the Editors:

Zhores Medvedev’s recent explanation (in the New York Times) of aspects of Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s personal life was quickly challenged by Natalya Reshetovskaya, the writer’s ex-wife. She felt—and apparently still does, despite Soviet exploitation of her resentment—that Medvedev’s selection of facts and interpretation of Solzhenitsyn’s motives and behavior was calculated to mislead the Western public. Whatever the rights and wrongs of this squabble, it established that ruptures have formed among Solzhenitsyn’s present and former close friends, and that Medvedev’s arguments, which shield Solzhenitsyn’s righteousness from any shadow of fallibility, are questionable. But in his review [NYR, May 17] of the biography of Solzhenitsyn by David Burg and me, Medvedev once again appears in the role of Solzhenitsyn’s advocate, telling a carefully chosen part of the truth and distorting the whole of the biography’s spirit while purporting to correct errors in parts.

My principal source for personal information about Solzhenitsyn was Veronika Turkina, who was related to the writer by marriage. When I saw her in Moscow in 1970 and 1971, she was very close to Solzhenitsyn, although this relationship subsequently suffered a reversal after searing recriminations by Solzhenitsyn and a terrible quarrel. Medvedev knows all this, knows that it was to protect Turkina (now living in the West) that she remained anonymous in the book, and knows that Turkina willingly gave me a mass of material which later—I had no way of guessing this—angered Solzhenitsyn because of its revelations and scope. Yet Medvedev’s way of presenting this complicated and unfortunate situation is to claim I did not interview any of Solzhenitsyn’s really close friends. This version has the advantage of simplicity, of avoiding mention or explanation of the Solzhenitsyn-Turkina estrangement and of shifting all blame for “prying” to me. Otherwise, it conceals more than it explains.

Shortly after arriving in London last winter, Medvedev telephoned me, and we agreed to meet in early March. I was delighted. Here was a chance to continue our discussion, previously carried on by letters from London to Moscow sent by a slow safe route, about all aspects of my research. Medvedev’s previous gracious help, and his association with Solzhenitsyn, convinced me to open all my notes to him. And I might learn what had caused Turkina and Solzhenitsyn to behave one way with me while I was in Moscow, but quite differently after I had left.

But Medvedev’s promised second call never came. Why? This was London, not Moscow: no need for precautions here. If Solzhenitsyn had asked him to sort out the controversy about the biography, what kept him from hearing my account of its preparation and from examining my materials? The only thing he had to lose was the one-sidedness which disturbed Reshetovskaya, and in which spirit his review is cast.

Medvedev’s methods seem extraordinary for a man of science and seeker of truth. Having kept himself from learning whom I interviewed, he declares that some of my information came from people other than Solzhenitsyn’s friends. Is this revealed knowledge? No, nonsense: in Moscow and elsewhere. I saw only people who knew Solzhenitsyn personally and were bursting with admiration and affection for him. But supposing I had seen someone whom Solzhenitsyn no longer considered a friend? Since when must a biographer limit himself to admiring sources? More than anything, Medvedev’s assumption that to see a non-friend would constitute a grave wrongdoing reveals what he expects from those writing about Solzhenitsyn: not biography but hagiography. The demand to follow guidelines falls into place with threats, intimidation, rumor, attempts to supress publication and Soviet-style standards in which terms our work has been discussed by Solzhenitsyn’s deputies.

Medvedev’s inexplicable reluctance to acquaint himself with my sources also permits him to write of “inventions” in the narrative of Solzhenitsyn’s life. When he is willing to investigate rather than pronounce, he will see that this is the invention; the book itself contains no word of it. He may also learn that on many matters his interpretation is highly questionable, and on others—the Presidium’s role in the publication of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, for example, and of Solzhenitsyn’s letter to the 1967 Soviet Writers’ Congress in the coming of the Prague Spring—it is simply wrong.

His review, in fact, abounds in errors, arbitrary judgments and false accusations. That he never heard a certain joke inspires two paragraphs of irrelevant de-bunking, based on the joke’s supposed non-existence. He dismisses our speculation that legal prosecution of Solzhenitsyn might perhaps have sparked off strikes as if we wrote in the present tense, whereas we were speaking of 1968, when—as we repeatedly emphasized—a distinctly less bleak political climate prevailed. In the crucial matter of Solzhenitsyn’s political impact, Medvedev uses the old device of refuting an argument put into an author’s mouth. We never wrote that Solzhenitsyn stands at the center of political opposition, but that he served as an inspiration for certain protestors and dissenters.

Still, these are secondary questions. The damage of Medvedev’s representations lies in his pretence that just these substantive issues are what caused the controversy about the biography. He knows that cliques have attacked it for allegedly endangering Solzhenitsyn’s position in Russia, and that some even say it was inspired by or “serves the interests of” the KGB. Although willing to dismiss these dangerous, Soviet-like allegations—the real spark of the uproar—as nonsense in private, Medvedev remains silent in print: something less than honorable as well as less than the whole truth.

In fact, while speaking of controversy, Medvedev avoids all its principal issues. Maybe I can guess why. Solzhenitsyn’s protest came in November 1971—ten months before the book’s publication, when it did not even exist as such. Although he fiercely condemns the odious Soviet practice of criticizing works of his which the Soviet public has not seen, Solzhenitsyn saw fit to vituperate, at a kind of international press conference, unpublished materials by Burg and me. And what incensed him was not chapters of the book, but an early draft. Is it accepted literary practice to denounce an author’s preliminary manuscripts? Moreover, these were brought into Russia by me at some risk precisely so that they could be read and corrected. And Solzhenitsyn never even saw the materials, but erupted on the basis of something he read about them, written by someone who also had not read them. Does anything more resemble the methods he abhors?

Although I wrote Medvedev over a year ago that the controversy could not be understood without taking this extraordinary lapse of literary ethics into account, he avoids all mention of it and of the morality involved. And, stretching and straining, writes a polemical review which tries, somehow, to justify Solzhenitsyn’s before-the-fact judgment.

I raise these matters not only to illustrate Medvedev’s bias, but because they lead to the heart of the controversy: should any biography of Solzhenitsyn be attempted at all? His denunciation of ours has been given wide publicity, but not his very different attitude while I was in Moscow. But although I asked Medvedev to look through Solzhenitsyn’s notes to me—notes he demanded be returned to him—for the words and answers which encouraged me to continue my unmistakably biographical (rather than literary) investigation, Medvedev says nothing too about this essential evidence. Yes, something angered Solzhenitsyn months after I left Moscow—but should we not have the story, once and for all, of who or what it really was?

I now doubt we will ever have these kinds of truths from Medvedev. Disturbed by a spate of forthcoming, unauthorized biographies of Solzhenitsyn, he is known to have written of ours, the first, as a warning to other “outsiders” bold enough to meddle. Not a word of his own writing about Solzhenitsyn goes beyond the narrow confines established by the subject himself. This raises the whole question of what limits and standards Westerners should adopt when writing about him. I believe we should maintain our own rather than accept Medvedev’s. It is not only that Solzhenitsyn, as a great writer, belongs to the world; he himself has made Solzhenitsyn a public figure. He has done this partly by making statements to the Western press when it served his interests—an entirely legitimate practice despite his scorn for journalism; but what of the limits he tries to set on what should be written about, and how? Newsmen who have felt the sting of Solzhenitsyn’s wrath will confirm that he does not fully understand the role and habits of a free press, but sees it in terms of how faithfully it transmits his will.

Solzhenitsyn’s appeals for free and open discussion—the evocative glasnost ringing from his letter after his expulsion from the Writers’ Union—are courageous and superb manifestoes. “Man’s salvation,” he wrote in his Nobel Prize lecture, “lies in everyone making it his business to know everything.” Yet his resentment of those who try to explain the phenomenon of Solzhenitsyn is powerful. Again in private, Medvedev has expressed an opinion about this puzzling contradiction—as well as Solzhenitsyn’s hot temper and rigid expectations of discipline from his friends. Perhaps it is time, as Solzhenitsyn wrote, to pull open some heavy curtains and allow the public to see for itself.

In a sense, all this is incidental (though not as much so as Medvedev’s quibbling). The main consideration is the wonderful gift of a writer of Solzhenitsyn’s stature in contemporary Russia. But we are mature enough to recognize his personal foibles without allowing this to tarnish his reputation as a writer and a public figure, or distort our perception of the authority which tries to suffocate him. Russia has given us enough saints, myths, and damage in this century not to make a new cult of Solzhenitsyn. Medvedev’s omissions—his attempts to make black-and-white of all the difficult questions—are to no one’s eventual benefit.

George Feifer

London, England

Zhores A Medvedev replies:

George Feifer’s letter, regarding my review of Solzhenitsyn by David Burg and George Feifer, does not constitute a reply to my critical comments. My main purpose in reviewing the book was to point out factual mistakes and misinterpretations, many of which were no doubt inevitable in the case of biographers who have never met their subject. I imagined that my rather mild review would be more gracefully received by the authors. I am therefore surprised by Feifer’s angry and purely speculative reply, in which he attacks not only me, but Solzhenitsyn himself—the latter for having criticized Feifer for the methods he used in gathering “personal information” about him.

Feifer now writes that his principal informant was Veronika Turkina (the cousin of Solzhenitsyn’s first wife) and that he refrained from identifying her as such, in order to “protect” her from possible reprisals at home in the USSR. The fact is, however, that Mrs. Turkina and her family had already emigrated to the West, and she was hence not in need of “protection” at the time when the Burg and Feifer book was still in galley proof; there was ample time for changes to be made in the book that would name her as a source. It seems more likely that Burg and Feifer neglected to mention Mrs. Turkina because she had vigorously and repeatedly objected to the substance of the book, and to the form that her frank talks with Feifer had assumed in print.

Yes, I did telephone Feifer in February, but not, as he says, to make arrangements with him to learn the identities of his confidential sources of information. There was indeed no need for this. The book had already been published and I regarded its authors, not their informants, as being responsible for its final content. My intention in phoning Feifer was to attempt to determine who had supplied a reviewer of the Burg and Feifer book with a lie about myself, which I later mentioned in my NYR review. I should add that Solzhenitsyn never asked me “to sort out the controversy about the biography.” He simply expressed the wish that I review the book, if I had the time and the inclination to read it. Since it is not available in the USSR, my unexpected trip to London offered me an opportunity to comply with his request.

It is evident that Feifer’s main objection to my review is that I did not reject as nonsense allegations that the biography “serves the interests of the KGB.” Feifer told me about such accusations on the phone, but he did not send me any articles or reviews wherein such views had actually been expressed. I can scarcely be expected to criticize statements which I have never read. Indeed, why should I discuss the matter of the KGB at all? Feifer would like me to be outspoken on this matter, but he fails to mention whose “interests” such a discussion on my part might serve.

Finally, Feifer criticizes Solzhenitsyn for his protest against the biography “ten months before the book’s publication, when it did not even exist as such.” In point of fact, Solzhenitsyn’s protest at the time did not single out Burg and Feifer by name. He protested only against the methods being used to gather information about him. He first identified Burg and Feifer by name, and as “rascals,” in an interview with American journalists, published April 3, 1972, when the book was most definitely in existence. Feifer suggests that he has notes from Solzhenitsyn purporting to approve his project. Actually, there was only one such note, written in 1970 and shown to Feifer by Mrs. Turkina. This asked Feifer to restrict the content of his book to literary analysis.

Solzhenitsyn’s concern about the biography in preparation was heightened when he learned of the identity of Feifer’s co-author, David Burg, from an ad that had appeared in a Western publication in 1971. Burg’s name was already known to Solzhenitsyn because of Burg’s active and public participation, together with the Slovak journalist, Pavel Licko, in the 1968 affair of the unauthorized publication of The Cancer Ward in the West. For Solzhenitsyn, the most troublesome event of his life in 1968 centered around the false authorization for the publication of his novel that had been furnished a British and an American publisher by licko. In their book, Burg and Feifer describe this episode in vague terms (“licko’s decision caused Solzhenitsyn anxiety and irritation at the time,” p. 272). But their assertion that Solzhenitsyn later reconsidered his view of licko (p. 273) is unequivocally wrong.

Feifer feels free in his letter to tell of a “terrible quarrel” between Solzhenitsyn and Mrs. Turkina. (Actually, it was not so “terrible.”) But he neglects to mention his quarrel with his own co-author which took place before the book was published, and even before Solzhenitsyn had singled out both authors for criticism. In a letter to me sent to the USSR in March, 1972, by what he calls “a slow, safe route” (safe for him, but not for me, I might add), Feifer expressed an opinion of Burg that hardly differs from Solzhenitsyn’s. I cannot make such judgments; I do not know either Feifer or Burg. But I have read their book and found it unsatisfactory. I was simply unhappy to read a bad, inaccurate biography of Solzhenitsyn. I am not, as Feifer claims, “disturbed by a spate of forthcoming, unauthorized biographies of Solzhenitsyn.” On the contrary, I welcome any future serious research about his work, his life, and his contribution to our culture. If Burg and Feifer should improve their book, in a subsequent revision, my own opinion of their work would improve.

Feifer asserts that I have privately said that Solzhenitsyn has a “hot temper and rigid expectations of discipline from his friends.” This is pure fabrication; I would never utter such nonsense. Solzhenitsyn is not hot-tempered and does not demand discipline. He has a kind temper and wants freedom. But above all, he wants the truth. And biographers cannot deny him this.

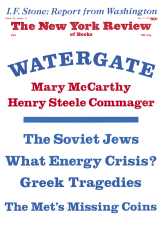

This Issue

July 19, 1973