Jan Kott’s new book is addressed to those who believe that plays are meant to be played: to the director, armchair or practicing, rather than to the literary critic. At the same time The Eating of the Gods can profitably be read against the ambiguous state of classical antiquity today. Are the classics still part of our “heritage,” something the educated person is supposed to know about, and if so in what sense? A field of force that, however forbidding, must even now be reckoned with? Or a chapter of Western intellectual history that is finally (thank heaven) drawing to a close?

Greek tragedy is one piece of ancient territory that we seem on the whole disposed to hold on to, and Kott’s claim, “the greatest dramatic cycle of all time,” can still just pass cultural muster. Yet if we do want to keep the Greek dramatists, it is far from clear how this is to be done: since so few people now know Greek. The approaches favored by present classical scholarship (especially in England) do not offer much help, nor is that any part of their purpose. This, the learned insist, is a difficult ancient convention that is wrenched out of kilter if we force it to satisfy modern interests.

In interpreting a Greek play, Geoffrey Kirk tells us, it is hazardous to follow our critical bent and assume “some complex and obscure personal intention by the playwright.” If we knew more of the myth he was dramatizing we would have a better answer. Another British scholar, Hugh Lloyd-Jones, a few years ago cautioned us against the kind of amateur incursion into classical affairs that Kott may be thought to have committed. Though full of errors, such a book is likely to go down well with the literary week-lies, “partly through the impression of up-to-dateness given by its invocation of various fashionable names, but partly because the modern-seeming travesty of its subject that it offers is more acceptable to some readers than a serious attempt at understanding would have been.”

One suspects that Professor Lloyd-Jones had this sort of thing in his sights, from Kott’s essay on Sophocles’ Trachiniae: “The naked Deianira, stomach slit [he has had her commit hara-kiri], lies on the nuptial bed in the house. Heracles is also naked.” If this is what the amateurs have to give us, some will prefer to settle for “a serious attempt at understanding” and as it happens Lloyd-Jones offers one himself in the book from which I quoted (The Greek World, 1962). He provides an account of the action which amply sustains his initial warning that the Trachiniae “by no means wholly conforms to modern notions of the dramatic” and then puts the question that should be uppermost in our minds: “Has the poet given us any insight into Zeus’ purposes?” The answer is yes. “Zeus has indeed brought about Heracles’ end, and so has given men one more reminder of his inexorable law of justice.” And? And nothing, that is what the play is about. After such knowledge, what forgiveness? It is enough to drive one back to Kott.

Scholarship, pursuing its own severe ends, will not preserve Greek drama as an active part of our culture. Perhaps we should look rather to translation, to those “many fine modern translations” that now supposedly exist. That Greek drama does somehow survive, despite translation, is a tribute to its own inherent vitality—or to human credulity. For of all great literary forms this is surely the most intractable. The “standard” versions, those in the Chicago series, incautiously overpraised by interested persons when they first appeared, are proving more deeply unreadable every year. Even the masters of modern verse translation met their match here. H.D., in the days of Imagism, marvelously suggested certain aspects of the Greek lyric but when she tried a whole play (Euripides’ Ion) she failed, though it is a failure from which there is much to learn. Pound himself, who found his way into Homer and Chinese and Latin elegiac and Old English, was defeated. His Women of Trachis, while at moments exhibiting more nobility of manner than anything in this field since Samson Agonistes, is a rag-bag of conflicting styles and does not come seriously to grips with Sophocles’ play.

Yet perhaps there is a way to recover what Artaud called the lost physics of this ancient theater that, in Greek, in the quiet of four walls, still keeps its first power. The way of production. Production can get round the greatest single obstacle, the untranslatable words; in the mouth of a good actor even the tamest diction may sound dramatically convincing. And production can deal with another obdurate feature of Greek drama, source of some of its greatest formal joys and most subtle effects, the lyric meters of the odes. They will not go into English; our poetry does not move to the cadence of consenting feet. They cannot be translated but they can be danced, as Kott has seen. Ajax, at the end of his second speech, tells the friendly chorus that he is going to a place where he will find “safety.” We know that he means death but they do not and a strange joy takes hold of them. Kott writes:

Advertisement

The soft boots beat faster and faster on the ground, the Chorus runs round the orchestra. “I would dance, I am bent upon dancing!”…[They] jump for joy between the scene of Ajax’s final reckoning with the world and that of his suicide. The frenetic dance of the Chorus, full of mirth and joyous shouts, is not only amazingly the-atrical, it has in it a sudden whiff of the absurd.

One could have done without that whiff of the absurd but the soft boots are attractive and Kott is on to something here. He has found his way into one of the great moments of Greek and especially Sophoclean tragedy, the moment just before disaster when the chorus, involuntarily caught up in the Dionysiac ecstasy, begin dancing: dancing immortal life against the onset of death.

Of course if the dance is Very Olde Greek, archeologically reconstructed from inadequate evidence, nothing will happen. But “if, instead of a stylized dance of the Chorus dressed in chitons,” Kott writes, “we imagine actors trained as in Grotowski’s theater, we will certainly be closer to the cruel theater of Sophocles.”

Kott’s aim, and certainly the aim is serious enough, is to do for Greek tragedy what he sought to do for Shakespeare. Shakespeare Our Contemporary did not please the scholarly community but it served to uncover a dimension of the plays concealed in those splendidly beknighted and bedamed English productions of a decade or two ago: splendid, but too cloistered. Mind in Shakespeare’s day walked dangerous streets and Kott’s background of contemporary European violence brought a needed danger back into Shakespeare. Above all, his essay on Lear fell into the right hands and set in motion a process that led to Peter Brook’s magnificent film.

The streets of fifth-century Athens were even more dangerous that those of Elizabethan London. Athens, Socrates said, was a place where anything could happen to anyone, a fact we would hardly guess from our tradition of interpretation. There has always been matter for ironic comedy in the contrast between the unshaded glare of ancient Greek life and literature and the umbratile paths of its practitioners. It is the glare, the “cruelty,” of Greek tragedy that Kott is everywhere in search of, and Deianira’s slit stomach is the price we must pay, the vicious extreme of a surely virtuous endeavor.

For at some level we have to read (and produce) Greek tragedy in the light of our own fullest sense of life—what other light do we have? This does not mean foisting our own preoccupations, on it, ideally quite the reverse. The paradox or fallacy of relevance is this: what we want from the literature and thought of the past must be something that we ourselves do not possess, a sound, as Stevens put it, “which is not part of the listener’s own sense.” The more we merely approximate the ancient experience to our own modes of understanding, softening it up for contemporary consumption, the less we can hope to receive. Major Greek poetry will, from the abyss of time, speak straight into your ear: but only if you keep the abyss. It is a fault of Kott’s approach that he too often fills in this necessary abyss with agitated allusions to Genet and Ionesco and Brecht.

The Greeks were very unlike ourselves; that is their value. Yet commerce with the past, to be worth anything, must be driven by cultural need. It seems likely that any past which is to command our attention now must offer some myth of the fall, and Greek tragedy meets this demand head on. That bare and essential stage exhibits the initial exhilarations of freedom; and the rapid discovery of its cost. Man, cut loose from his archetypes, no longer part of the enfolding whole, comes to know the terrors, and the pride, of isolation. Above all in Sophocles, whose most representative heroes, Ajax, Antigone, Oedipus, have in the end nothing to hold on to except the indestructible sense of their own greatness.

But the words I have just written are hardly part of modern reading and Kott finds a better or at least a more contemporary way into these distant plays. In his essay on the Ajax, for example, where he shows his hand in the first sentence. “My name is Ajax: agony is its meaning.” Supposedly the earliest of his surviving plays, the Ajax deals with Sophocles’ lifelong theme, heroism. Or rather, Kott would say, the difficulty of heroism in a post-heroic age. Deprived of the arms of Achilles that were his by right, Ajax tried to kill the Greek leaders but Athene darkened his mind and instead he butchered a herd of cattle. Returning to sanity, knowing that he has become “alien to men and alien to the world,” Ajax confronts the central of his being.

Advertisement

He is brought to that typically Sophoclean moment, Kott writes, when “the protagonist finally realizes that the ground is being cut from under his feet, and the gods are silent. Only then, in full awareness of the human condition, is a heroic choice possible: to commit suicide or to go on living, and…defy the absurd of the world through continuing in life.” Camus, yes, but also Sophocles, who faces Ajax with the heroic choice in its most rigorous form: “Either to live well [proudly, Nietzsche translated] or to die well befits the noble mind.” Ajax, very grandly, chooses death and kills himself. A heroic act? No, an act that, occurring in a post-heroic age, is necessarily meaningless, or cannot have the meaning that Ajax intends.

The play is only a little more than half way over when Ajax dies, and the second half wrestles with the sense, or non-sense, of his act. With the enormous corpse visibly on stage (Kott keeps a director’s eye on its imposing size), the Greek leaders acrimoniously debate what is to be done with this heroic encumbrance. The scene has puzzled and distressed critics but it plays into Kott’s Polish hands:

The bickerings bring no catharsis. It is not by chance that the bitterness of Ajax has been understood in times when people have come to know from their own experience about corpses thrown into a rubbish heap, hasty exhumations and invariably belated rehabilitations, connected with the cult of new leaders.

It is his old enemy Odysseus, “the pious politician,” who wins the day by securing for Ajax a decent burial and—a hero’s tomb. The last twist of the knife, and Ajax emerges as a properly defeated hero of our time, his fate grotesque rather than tragic and thus excluding any form of consolation.

This plainly is a contemporary reading, yet in a sense Kott’s approach is more traditional than that of scholars who would lock up Greek tragedy impenetrably, and uselessly, in the fifth century BC. The classic, we used to believe, shows a new face to each generation; that is why we call it classical. Kott takes his liberties, of course, but he does not throw caution, or Sophocles’ text, to the winds, and if, critically, he has nothing very new to say, he succeeds in opening up a stiff ancient play for modern reading—and modern performance.

Aeschylus receives only one essay, an unduly archetypal piece on the Prometheus Vinctus which draws so heavily on Eliade, Northrop Frye, Rousseau, Marx, Lévi-Strauss, Kafka, and other worthies that there is little space left to say much of value about Aeschylus’ play—which Kott for some reason regards as the second member of the Prometheus trilogy, rather than the first. Euripides, perhaps because he is not thought to need so many extraneous big guns to make him interesting, fares better and the essays on the Alcestis and the Bacchae are worth reading.

In “The Veiled Alcestis” Kott does nothing to impair the ambiguity of an already ambiguous play but—or perhaps and—he provides the materials for a stimulating performance. Or rather, two performances: a wry comedy or, if you prefer, a very dark pièce noire. The chorus have just finished an ode on the universal anagkê of death when Heracles comes in with a veiled woman. Admetus, the fable says, uniquely privileged by Apollo, can escape death on condition that his wife Alcestis will die for him.

Not looking very deeply into this singular exemption, he lets Alcestis die: to find that the life she has preserved is not worth living. So his guest-friend Heracles goes off and returns with a mysterious woman. Admetus’ dead wife brought back from the grave, we are invited to think, but there are several hints in the prolonged recognition scene that things are not what they seem and that the veiled figure may be, as the text at one point suggests, a “phantom from the dead.” She removes her veil and Admetus seems to recognize her. I’ve been lucky, he says, taking her with him into the palace. However, the opening scene of the play can be made to throw a disturbing light on its close. As Kott puts it: “In the prologue Death comes for Alcestis; in the epilogue Alcestis, raised from her grave, comes for Admetus.” I’ve been lucky, the unfortunate man says, taking her with him into the palace.

The Bacchae, a greater play, receives a more sober treatment. Issuing a welcome warning to directors “who think they can forget the discipline of tragedy when staging the Bacchae,” Kott refuses to go overboard into the beckoning Dionysiac deeps and rightly stresses what in the play is not ritual:

…two separate and contradictory structures co-exist. The eating of the god, the rite of death and renewal, becomes in the end a cruel killing of son by mother. The ritual turns into a ritual murder.

Sacred and profane here meet and collide. The sacred puts forth its awesome power, its beguiling promise of freedom from the principle of individuation. The sacred—Dionysus—wins, as it must, and the god’s enemy Pentheus is horribly punished, along with his whole family. But then poor shattered humanity regroups and reasserts, uselessly but very movingly, its own human standards, judged by which the divine punishment is seen as not merely inhuman but subhuman. As Kott rather finely says, “The profane…still retains its power of refusal.”

Lively and often suggestive, Kott for the most part does not work close enough to his texts to take us into the dark places of Greek tragedy. What he has done is to keep a number of plays in circulation and show that they belong not only to the study but to the stage: a modern stage that, having rediscovered ceremony and spectacle, the language of gesture and mime, and learned from the nondiscursive, symbolic drama of the East, may prove more hospitable to the Athenian masters than the traditional Western stage has been. And, with Brook’s film of King Lear in mind, one may see a future for them in the cinema. With its simplification of plot line and severely archaic setting, the filmed Lear was Greek as well as Shakespearian. Dare we look forward to a Brook film of the Oresteia or the Oedipus Rex, translated by Ted Hughes into Orghast and from there into some urdichterisch English…? One day, perhaps, reflecting on these scarcely imaginable masterpieces, we may say: Strange that the first seeds should have been in The Eating of the Gods.

This Issue

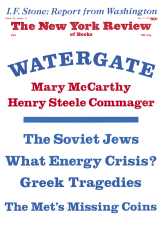

July 19, 1973