Even before Nixon went into Bethesda Naval Hospital, the estimate in Washington was that he could not weather Watergate. Yet this came at a time when the Senate hearings were faltering. The caucus room all week had a new atmosphere, of disaffection, boredom, almost disgust. The performances of the Ervin panel senators, the quality of their staff work were reviewed by journalists with mounting impatience. The press tables stood partly empty, and the front-row VIP seats were denuded a good deal of the day. At one of the long, semideserted press tables Wednesday afternoon a small child sat drawing airplanes and what looked like big bombs in red crayon on a sheet of yellow paper, which he then folded into a glider, unfortunately aimless. Photostats of the Mitchell logs lay around collecting dust; many who got them as a handout did not bother to take them home.

The credit or responsibility for this devastation belongs to John Mitchell, whose sodden-voiced testimony occupied most of three days that came to resemble eternity in its hellish aspect. Outside, early in the week, an airpollution alert had been sounded, as if in sympathy: people with eye or respiratory problems were warned to make no exertion and/or to stay indoors; according to rumor, a radio broadcast had told the population to refrain from drinking tea and coffee, though not, apparently, alcohol. There can be no greater boredom, I think, than that engendered by a steady dosage of lies. As Mitchell testified, the occasional laughter of the first day that met his toneless disavowals, the hiss that susurrated once through the room were replaced by an almost total sound vacuum, which in some dulled helpless way matched the calculated void of his contribution.

It was true that the performances of the senators—with one exception—and of counsel were poor, but they had had him Monday in executive session and thus got a preview of the public charade. That they had come out of that wilted and blanched was understandable, for there was nothing human or responsive in the element they had been immersed in. Stone-walling, Senator Weicker, the only brave man of the week, called it, borrowing the phrase, in fact, from the sinister White House lexicon. Trying to get a direct answer from John Mitchell was like beating your head against a stone wall. Faced with two diametrically opposed statements given under oath by himself, he blandly declined to see any contradiction. Weicker, angry: “Is this your definition, by the way, this kind of testimony, of, what is the expression, of ‘stone-walling it’?” Mitchell, insolent: “I don’t know that term. Is that a Yankee term from Connecticut?”

The fear of another perjury indictment—he has been charged already in New York—might seem to be a rational explanation for his obtuseness to any trace of contradiction when shown two of his own statements one of which cannot be true. Yet to play blind to a contradiction does not prevent others from perceiving it. Moreover, the Senate panel, far from being out to “get” Mitchell, appeared bent merely on getting some truth out of him, using those discrepancies, finally, as a press to squeeze it out. But it was a case of trying to get blood from a turnip, and indeed there was something turnipy about Mitchell, the off-white (or tattletale gray) face with occasional mottlings of purplish pink, the watery, squelchy voice, the smooth bald pate.

He was educated, at Fordham University and Fordham Law School, by the Jesuits, though he is a Protestant, and vocally and visually he has that root-cellar quality of the Jesuitic world, at least as I knew it in my Catholic childhood—the small lifeless eyes, like those of a wintering potato, the voice sprouting insinuations. He is supposed to have been an athlete, a hockey player and golfer, but you would never guess it to look at his sedentary outline, sloping-headed, slope-shouldered, slope-nosed, without tone or elasticity. The mind is not supple, merely practical in weary equivocation.

When I started listening to Mitchell, I did the normal thing—tried to ask myself what elements of truth there were in the story he was telling. For instance, about the Liddy plan. All accounts agreed that it had been presented to him three times, and on a descending scale of grandiosity, the first two in his Attorney General’s office at the Justice Department, the last on March 30 at Key Biscayne. All accounts agreed that he had twice rejected it. Magruder said that the third time he had given a reluctant consent. Dean, who had not been present at Key Biscayne, was unable to testify on the point. Mitchell himself denied that he had ever given his approval. On the contrary. “We don’t need this. Out. Let’s not discuss it any further.” According to him, he assumed that the project had been killed then and there. When he heard of the Watergate break-in, it did “cross his mind” that this was the old Liddy plan, finally put into operation, but he dismissed the thought because “the players were different”—McCord and some Cubans. Not, seemingly, Liddy, whose involvement did not come to light until later.

Advertisement

Plausible, so far, though maybe not likely. Mitchell’s word against Magruder’s. The only backing for Magruder’s story came from Hugh Sloan and McCord, who said Magruder had told them that Mitchell had given his approval, and from another witness, Reisner, who said that the Gemstone material—the code name for Watergate—had been in a file marked “Mitchell.” But perhaps that could be explained.

In Mitchell’s favor was the fact that Magruder, a Haldeman boy, had seemed, at least to me, an untrustworthy witness bent on playing the White House loyalist game of fingering Mitchell and Dean. And if it did not seem possible that the quite junior Magruder could have okayed Watergate on his own, in defiance of Mitchell’s express order to drop it, it might be that Magruder had been acting on instructions from some higher authority. “In hindsight,” Mitchell now said (his own tough euphemism for some mixture of conscience and common sense), he thought there had been pressures on Magruder. When asked by the Majority counsel if these pressures could have come “from above,” Mitchell grew wary. They could have come from “collateral areas” not necessarily from above. He declined to “speculate,” but “collateral areas” meant Colson, as the initiate immediately understood.

Up to now, the story held up—just barely. But from that point on, all questions glanced off him. He denied having had the faintest awareness of any activity leading up to the break-in. Hadn’t he authorized a “substantial sum” to be paid to Liddy? No, that was Magruder. But Sloan said differently, Stans said differently.

Dash: Let me just read to you, Mr. Mitchell, Mr. Stans’s testimony: “I said, do you mean, John, that if Magruder tells Sloan to pay these amounts or any amounts to Gordon Liddy, that he should? And he said, ‘That is right.’ ”

Mitchell: Well, I would respectfully disagree with Mr. Stans.

No attempt was made to lend some minimal plausibility to his denials, to his repeated “I don’t recall” concerning crucial incidents. On a single occasion: “Must be a confusion of persons.” The weariness and boredom of his voice suggested that all this was ridiculous, preposterous, but also that he could not take the trouble to construct a lie that somebody might conceivably believe. He seemed rancorously determined to insult the intelligence of the committee, the press, the TV audience—everybody, the world at large. His testimony was held together not in the usual way, in terms of general likelihood and known facts outside itself, but by an inner wooden logic based on speaking for the record. When examined, it would contain nothing tending toward an admission. In other words pointing toward truth or reality.

Hence the interrogation grew so intolerably boring. There was no element of danger that can make clever lying, up to a point, exciting to the liar and to those who watch and listen, since clever lying always has large amounts of truth mixed into it, which both tend to support the fabrication and imperil it: even little bits of truth may undo you by hanging together in an unforeseen way.

With the ex-Attorney General, one did not feel oneself in the presence of even half- or quarter-truths, which one might start trying to piece together with other information to get a reasonable whole. To do that, one has to disregard every statement and non-statement about Watergate made by Mitchell under oath to the Senate committee. Except for the initial assertion: that he did not approve the third presentation of the Liddy plan at Key Biscayne. Accepting that provisionally as true, how can we interpret what followed? Suppose he soon sensed, when consulted about those large sums for Liddy, that someone else had approved it over his head, someone, singular or plural, who had been pushing it all along, someone who had sold the notion to the President (or hadn’t, whichever seems more likely). When the project came up the third time, over his double veto, Mitchell must already have known, and not by hindsight, that powerful forces were sanctioning it. So what did he decide to do? Play along and play possum. If the scheme succeeded, he was in the clear, having taken no further steps to block it. If it failed, he was in the clear, since his opposition was, he thought, on the record. If it succeeded, the team as a whole gained; if it failed, his enemies on the team would be discredited. Nothing would be lost by keeping a “low profile.”

Advertisement

He may not have rated the risks of the operation high enough and have thought more in terms of financial gamble, seeing the plan as a probable waste of campaign funds, than in terms of the burglars actually getting caught on the premises and with Committee money and a White House telephone number on them. Hitherto, in the various plumbers’ and dirty tricks forays, nobody had been caught, and one may assume (if one wants) that Mitchell knew about them, despite his denials to the Senate panel. Anyway he did not foresee that the burglars would let themselves be caught flat-footed, thus depriving the CRP of precious “deniability,” which it still would have had if they could have got away, leaving only the “bugs” and signs of forcible entry behind them.

The sequel can be outlined almost any way you like. After the break-in, Mitchell told Nixon what he knew. Or he did not tell him. Either because he knew Nixon knew already or because he was not sure whether Nixon knew or not and wanted to leave him that same deniability. It may be a literal fact that Nixon never asked him, although many people find that unbelievable. It is unbelievable if you assume Nixon knew nothing, but if you take the opposite assumption, there is no problem. The possibility offered by Mitchell—that Nixon did not know and never asked—would be believable only on one condition: Nixon is a psychopath who adhered throughout Watergate to his own paranoid certainty that everything disseminated by the media is false and hence of no interest, except as further evidence of a design to persecute him.

That, even so, his entourage did not seek to alert him appears strange, unless fear was the reason. Mitchell testified that he did not tell the President the horrors that had been going on for fear that he would “lower the boom,” meaning fire everybody concerned and thus create a noisome scandal. Yet, as Senator Inouye pointed out, if and when the President at last learned something approaching the truth, no boom was lowered: only Dean, who had been warning him, like the king’s messenger, about the spreading “cancer,” got the axe. So if there was general apprehension about Nixon’s conduct were the facts to reach him, it may not have been dread of a rational response, such as a strenuous housecleaning. Indeed, as was shown in Dean’s testimony and again, Friday, in that of the fatherly media expert Richard Moore, Nixon’s actual responses to Watergate disclosures were alarming in their dreamy inertia. Moore advised him forcefully on April 20 to get outside counsel. “And what did the President do?” “He went to Key Biscayne.”

Mitchell’s reason, as given by him, for shielding Nixon from the realities was not Watergate, which he dismissed as insignificant, but the knowledge he had gained from Liddy, via Dean and Mardian, of the “White House horror stories.” This, it transpired, was another of Mitchell’s private code names for Colson, the promoter of Hunt and Liddy. The horrors comprised the kidnapping of Dita Beard by Hunt wearing a red wig, the raid on the office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist, the forging of the Diem cables, the project for fire-bombing the Brookings Institute, “extra-curricular wiretapping,” the undercover spying at Chappaquiddick. He did not name any others, preferring cryptic innuendoes to what he called “specifics.”

He did not care for the words “cover-up” and “perjury.” “What is being referred to here as the cover-up,” he would repeat, and for lying under oath, “We were not volunteering information.” On the other hand, he was fond of “the Democrat National Committee,” “the Democrat party,” which raised the specter of the late Senator Joe McCarthy, who from policy never said “Democratic,” seeming to feel that clipping a syllable from the name was a magic exercise, like clipping bits of your enemy’s toenails to snip his vital forces. “Democrat,” in Joe McCarthy’s and Mitchell’s evil parlance (and also, by the way, in Senator Gurney’s), seemed to do double duty as a cipher for leftish, Commie-tainted.

Mitchell brought evil into the caucus room, and this was not unconnected with the boredom he was able to generate—many thought deliberately—turning spectators who had been constituting a sort of town meeting into a restless, anomic, apolitical crowd. After several days of him, nobody cared whether Nixon knew or not, whether Haldeman and Ehrlichman planned the cover-up, or even whether Mitchell’s own toneless and nonresponsive testimony was being motivated by the earlier threats from the White House implicit in the show of force of the Buzhardt memo, disavowed when Mitchell (perhaps?) agreed to play ball.

Curiosity revived when Richard Moore took the witness chair. Fifty-nine years old, pictured by himself as a “source of white-haired advice and experience” for the President (born a year earlier than he), a prominent Son of St. Patrick and former head of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, this White House Nestor restored the atmosphere to something resembling normal, even though he appeared to be in his dotage and had practically nothing to contribute—his testimony, which was supposed to controvert Dean’s, in fact corroborated it on almost every point. The forgetful old Republican may have seemed to be foolish, prosy, rather vain, but he also seemed to believe that he was telling the truth or something close to it. At least until Friday when Senator Weicker caught him in an obvious prevarication on one of the Watergate subsidiary matters and he too began to stone-wall, though with more agitation than Mitchell had shown. His main fault, though, was a sort of commercelaved innocence. He had thought (and probably still does) that the Watergate cancer could be cured by salesmanship: “Mr. President, why don’t we get the story out ourselves?”

There was a long moment, though, on Wednesday when Mitchell’s answers awakened sparks of interest. Senator Baker was interrogating, and the area he was covering, that of judgment and opinion, no doubt seemed safe to the witness. He could afford candor; nobody will slap a perjury indictment on you if you stick to ideas. Senator Baker: “What is your perception of the institution of the Presidency?” Mitchell allowed that that would take a long time to answer, but then answers started popping out of him like sulphurous firecrackers. His perception of the institution was that he was unable to contemplate anybody but Richard Nixon in it, as though the Presidency had become unique with Nixon’s incumbency, different from anything previous and requiring self-succession. He had already stated that, for him, the re-election of this particular President was paramount and justified the cover-up.

He now went on to say, with a brief touch of pious enthusiasm, that the President could not deal “with all the mundane problems that go on from day to day.” He himself had spared him knowledge of the “horror stories” and incidentally Watergate (how a horror story could be mundane was not clear) to relieve him of the need to decide what to do about them. “I had to keep his options open.” A decision, if taken, “would have impeded his potential for re-election.” “I was not about to countenance anything that would hinder that re-election.”

All this was said in tones of self-evidence: he was setting out propositions so axiomatic that they needed no demonstration. Nor did he seem to be aware of the enormity of what he was enunciating—a doctrine of a higher law transcending the Constitution, incarnate in the figure of our old friend Tricky Dick. He made not the slightest allusion to policies that might call for continuance but merely insisted on the person of Nixon (whom he also referred to as “the individual”) whose sole function seemed to be getting re-elected, like a perpetual-motion machine. This then, pulling at its pipe, was a sample of a protofascist mentality or its deposed Grand Vizier. We had half expected some revelation of the kind from the “Germans” Haldeman and Ehrlichman but hardly from an old-style, coarse, crony-type law-and-order politician and backroom mouthpiece.

The relations of the Nixon band among each other, shadowing forth the parallel structures of totalitarian organizations (see Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism), received—and not for the first time in these hearings—a little illumination from the Mitchell testimony, and this ray of light too was cast almost inadvertently, as if casually, when Mitchell “happened” to mention a detail of an interview with Ehrlichman that took place this last mid-April in Ehrlichman’s office. Mitchell was out of the power arena, his usefulness having ended when the lid started blowing off the cover-up; at earlier meetings the two had sat at a coffee table. Now they sat near the desk as Ehrlichman questioned him about the extent of his Watergate involvement. The shift in the seating arrangements, duly noted by Mitchell, was not just emblematic; he instantly surmised, as if it were the most natural thing in the world, that there was a listening-device hidden somewhere in the region of the desk.

We learned the following Monday what according to a witness Mitchell didn’t know and Ehrlichman didn’t know: the leader has listening devices that, turned on automatically by a sort of person- or President-sensor, record the merest whispers uttered in his ambience.

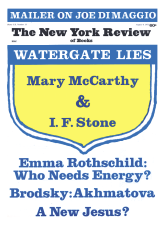

This Issue

August 9, 1973