Giraffes, how did they make Carmen? Well, you see, Carmen ate the prettiest rose in the world and then just then the great change of heaven occured and she became the prettiest girl in the world and because I love her.

Lions, why does your mane flame like fire of the devil? Because I have the speed of the wind and the strength of the earth at my command.

Oh Kiwi, why have you no wings? Because I have been born with the despair to walk the earth without the power of flight and am damned to do so.

Oh bird of flight, why have you been granted the power to fly? Because I was meant to sit upon the branch and to be with the wind.

Oh crocodile, why were you granted the power to slaughter your fellow animal? I do not answer.

—Chip Wareing, fifth grade, PS 61

I

Last year at PS 61 in New York City I taught my third-through-sixth-grade students poems by Blake, Donne, Shakespeare, Herrick, Whitman, William Carlos Williams, Wallace Stevens, John Ashbery, and Federico García Lorca. For several years before, I had been teaching poetry writing to many of these children, and they liked it so much that I thought there must be a way to help them read and enjoy great poetry by adults.

I found a way to do it, in conjunction with my students’ own writing, which enabled the children to get close to the adult poems and to understand and enjoy them. What I did, in fact, was to make these adult poems a part of their own writing. I taught reading poetry and writing poetry as one subject. I brought them together by means of “poetry ideas,” which were suggestions I would give to the children for writing poems of their own in some way like the poems they were studying. We would read the adult poem in class, discuss it, and then they would write. Afterward, they or I would read aloud the poems they had written.

When we read Blake’s “The Tyger” I asked my students to write a poem in which they were asking questions of a mysterious and beautiful creature. When we read Shakespeare’s “Come Unto These Yellow Sands,” I asked them to write a poem which was an invitation to a strange place full of colors and sounds. When we read Stevens’s “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” I asked them to write a poem in which they talked about the same thing in many different ways. The problem in teaching adult poetry to children is that for them it often seems difficult and remote; the poetry ideas, by making the adult poetry to some degree part of an activity of their own, brought it closer and made it more accessible to them. The excitement of writing carried over to their reading; and the excitement of the poem they read inspired them in their writing.

I had used poetry ideas in teaching my students to write poetry before, to help them find perceptions, ideas, feelings, and new ways of saying things, and to acquaint them with some of the subjects and techniques they could bring into their poetry; I had proposed poems about wishes, dreams, colors, differences between the present and the past, poems which included a number of Spanish words, poems in which everything was a lie.* I would often suggest ways of organizing the poem as well: for the Wish Poem, starting every line with “I wish”; to help them think about the difference between the present and the past, I suggested alternating line-beginnings of “I used to” and “But now”; for the Comparison Poem I suggested they put one comparison in every line, for a Color Poem the name of a color in every line. These formal suggestions were most often for some kind of repetition, which is natural to children’s speech and much easier for them to use in expressing their feelings than meter and rhyme.

With the help of these poetry ideas, along with as free and inspiring a classroom atmosphere as I could create (I said they could make some noise, read each other’s lines, walk around the room a little, and spell words as best they could, not to worry about it), and with a good deal of praise and encouragement from me and from each other, my students in grades one through six came to love writing poetry, as much as they liked drawing and painting, sometimes even more—

The way I feel about art is nothing compared to the way I feel about poetry.

Poetry has something that art doesn’t have and that’s feelings….

—Rafael Camacho, 61

My poetry ideas were good ideas as long as they helped the children make discoveries and express feelings, which is what made them happy about writing—

Advertisement

I like poetry because it puts me in places I like to be….

—Tommy Kennedy, 6

You can express feelings non-feelings trees anything from A to Z that’s why

IT’S GREAT STUFF!

—Tracy Lahab, 6

They wrote remarkably well. Sometimes my students wrote poems without my giving them an idea, but usually they wanted one to help them get started to find new things to say.

Teaching students who were enthusiastic about poetry, good at writing it, and eager to get ideas for writing new poems, I considered the kind of poetry that they were usually taught in school (and the way it was taught) and I felt that an opportunity was being missed. Why not introduce them to the great poetry of the present and the past? It was a logical next step in the development of their own writing: it could give them new ideas for their poems, and it would be good in other ways too. If they felt a close relationship to adult poetry now, they could go on enjoying it and learning from it for a long time.

This result seemed unlikely to be produced by the poetry children were being taught in school. The poems my students wrote were better than most of those in elementary-school textbooks. Their poems were serious, deep, honest, lyrical, and formally inventive. Those in the textbooks seemed comparatively empty and safe. They characteristically dealt with one small topic in an isolated way—clouds, teddybears, frogs, or a time of year—

…Asters, deep purple,

A grasshopper’s call,

Today it is summer,

Tomorrow is fall.2

Nothing was connected to any serious emotion or to any complex way of looking at things. Everything was reassuring and simplified, and also rather limited and dull. And there was frequently a lot of rhyme, as much as possible, as though the children had to be entertained by its chiming at every moment. When Ron Padgett at PS 61 asked our fifth-grade students to write poems about spring, they wrote lines like these—

Spring is sailing a boat

Spring is a flower waking up in the morning

Spring is like a plate falling out of a closet for joy

Spring is like a spatter of grease….

—Jeff Morley, 5

Jeff deserved “When daisies pied and violets blue” and “When as the rye reach to the chin” or William Carlos Williams’s “Daisy” or Robert Herrick’s “To Cherry Blossoms,” rather than “September.” If it was autumn that was wanted, I’m sure that with a little help he could have learned something from “Ode to the West Wind” too. There is a condescension toward children’s minds and abilities in regard to poetry in almost every elementary text I’ve seen:

Words are fun!… Some giggle like tickles, or pucker like pickles, or jingle like nickles, or tingle like prickles. And then…your poem is done!

And so is my letter. But not before I wish you good luck looking through your magic window…3

says one author to third graders; but my third graders could write like this:

I used to have a hat of hearts but now I have a hat of tears

I used to have a dress of buttons but now I have a name of bees….

—Ilona Baburka, 3

I had discovered that my students were capable of enjoying and also learning from good poetry while I was teaching them writing. In one sixth-grade class I had suggested to the students a poem on the difference between the way they seemed to be to others and the way they really felt deep inside themselves. Before they wrote, I read aloud three short poems by D. H. Lawrence on the theme of secrecy and silence—“Trees in the Garden,” “Nothing to Save,” and “The White Horse.” They liked the last one so much they asked me to read it three times:

The youth walks up to the white horse, to put its halter on

and the horse looks at him in silence.

They are so silent they are in another world.

The Lawrence poems seemed to help the whole class take the subject of their poems seriously, and one girl, Amy Levy, wrote a beautiful and original poem which owed a lot to the specific influence of “The White Horse.” She took from Lawrence the conception of another world coexistent with this one, which one can enter by means of secrecy and silence, and used it to write about her distance from her parents and the beauty and mystery of her own imaginings—

We go to the beach

I look at the sea

My mother thinks I stare

My father thinks I want to go in the water.

But I have my own little world….

In my new teaching my aim was to surround Amy, Ilona, Jeff, and the rest of my students with other fine poems, like Lawrence’s, that were worthy of their attention and that could give them good experiences and help them in their own writing. Some of the poems would be much more difficult than “The White Horse,” and all of them would probably be “too hard” for the children in some way, so I would not merely read the adult poems aloud but do all I could to make them clear and to bring the children close to them.

Advertisement

II

I began with the general notion of teaching my students the poems I liked best, but I soon saw that some of these were better to teach than others. Some poems came to me right away because of some element in them that I knew children would be excited by and connect with their own feelings. The fantasy situation in Blake, for example, of talking to an animal—or the more real-life situation in Williams’s “This Is Just to Say” of apologizing for something you’re really glad you’ve done. Certain tones, too—Whitman’s tone of boastful secret-telling. And strange, unexpected things, like Donne’s comparisons of tender feelings to compasses and astronomical shifts.

Sometimes a particular detail of a poem made it seem attractive: the names of all the rivers in John Ashbery’s “Into the Dusk-Charged Air”; the colors in Lorca’s “Arbole, Arbole” and “Romance Sonambulo”; the animal and thing noises in Shakespeare’s songs (bow-wow, ding-dong, and cock-a-doodle-doo).

Some poems had forms that suggested children’s verbal games and ways children like to talk, such as the lists in Herrick’s “Argument” and in Stevens’s “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” or the series of questions in “The Tyger.” Such forms would be a beginning for a poetry idea, since they were something the children could imitate easily when they wrote.

It was usually one of these appealing features that brought a poem into my mind as good to teach children. Of course, I wanted it to be a poem they could get a lot from. There are terrible poems about talking to animals and there are great ones. And the same for lists, strange comparisons, and the rest. I was looking for appealing themes and forms in the very best poems. “The Tyger,” speaking to children’s sense of strangeness and wonder, could heighten their awareness of nature and of their place in it. Herrick’s “Argument” would help them to think about their poems in a new way, somewhat as they might think of places they had been or of specific things they had seen and done. Donne’s poem could show them connections between supposedly disparate parts of their lives. Whitman could encourage them to trust their secret feelings about the world and how they were connected to it—it told them these feelings were more important than what they found in books. “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” showed the interest, the pleasure, and the intelligence of looking at the same thing in all kinds of ways. The Williams poems showed how poetry could be about very ordinary things. Ashbery’s poem, like Donne’s, could help them bring together a school subject—in this case, geography—in a playful and sensuous way with their feelings, and with poetry.

One thing they could learn from them all was the importance of feelings and of one’s secret imaginative life, which are so much what these poems are about. They were learning what great poetry had to do with them. Feelings they may have thought were silly or too private to be understood by anyone else were subjects that “great authors” wrote about. One reason I chose to teach Shakespeare was to show the children their connection to the poet they would be hearing about so often as the greatest who ever lived.

In deciding on poems, I wasn’t put off by some of the difficulties teachers are often bothered by. Unfamiliar words and difficult syntax, for example, and allusions to unfamiliar things. My students learned new words and new conceptions in order to play a new game, or to enable them to understand science fiction in comics or on TV, so why not for poetry, which they liked just as much? Furthermore, since they were going to write poems themselves, the lesson did have something of the atmosphere of a game; and if they didn’t find the poems as interesting as science fiction, I would have to figure out what was wrong with my teaching. In fact, in the excitement of reading the poems, the children were glad to learn the meanings of strange words, of old forms like thee and thine, and of strange conceptions like symmetry and sublunary.

I wasn’t put off, either, by passages in a poem that I knew would remain obscure to them. To reject every poem the children would not understand in all its detail would mean eliminating too many good things. I knew they would enjoy and get something fine from Stevens’s blackbird, even if the ironic allusiveness of “bawds of euphony” was going to escape them; and I was sure they would be inspired by Donne’s compass even though certain details about neo-Platonism and Ptolemaic astronomy would be too hard to explain.

Though it occurred to me, at first, to reject all poems with sex or religion as part of their subject, I decided it was all right to teach poems that dealt with these subjects in certain ways. The sexual theme in Donne’s “Valediction” is implicit but not the main theme of the poem; the real emphasis is on love, the pain of parting, and the hope for reunion, all of which children can respond to. Blake’s “The Tyger” is not sectarian in a way that might bother children, but touches on religious feelings of a more basic kind. Children can feel wonder and amazement and fear, and they are fascinated by superpowered beings; they can respond without difficulty to the Creator of the tyger.

Like its textural and thematic difficulties, a poem’s length can make it seem impossible to teach to children. I thought if something about the poem was just right for my students, however, that it was all right to teach them only a part of it, which is what I did with “Song of Myself.” I chose sections 1 and 2; in class I explained the relation of these parts to the rest of the poem. There was no short poem by Whitman that I thought would teach them as much. I felt free also to select poems in another language if they had something fine in them for my students, as I thought several poems of Lorca did. I gave the children the poems in Spanish and in English translations. Translations are imperfect, and only a few children understood all the Spanish, but the good things here (the dreaminess, the music, the use of color, the contrast of original and translation itself) seemed to outweigh these disadvantages.

Rhymed poems and poems written in the language of the past could have had bad effects on my students’ writing, but I didn’t want to omit such poems. I dealt with rhyme by showing my students the other kinds of form there were in the rhymed poem—the series of questions, for example, in “The Tyger,” and the repetition of words—and suggested they use that kind of form in the poems they wrote in the lesson. Along with the rhymed poems, I included some that didn’t rhyme—those by Whitman, Stevens, Williams, and Ashbery. I explained the present-day equivalents of all out-of-date words and phrases in the poems, and, while the children wrote, I urged them to use the words they really used when they spoke.

After five lessons on past poets, I did notice some conventional “literariness” in their language and in the subjects they wrote about. I didn’t wish to discourage all literary imitation, since sometimes it helped the children to express genuine moods and feelings, such as awe and grandeur, which they might not have been able to express without it. However, I didn’t want them to get lost in it. So I taught them Williams, who wrote in contemporary language about ordinary things. The example of a great poet who did this, I thought, would help the children do it for themselves.

What I saw in my students’ own poetry was helpful to me in choosing poems to teach them. The extravagance of their comparisons in earlier poems (“The cat is as striped as an airplane take-off…”) had something to do with my deciding on Donne. José Lopez’s poem about talking to a dog (“Oh dog, how do you feel with so much hair around you?”) was one thing that put Blake’s “The Tyger” in my mind. The tone of secrecy in the poems my students wrote inspired by Shakespeare’s songs made me think of teaching Whitman and of emphasizing a tone like that in his work. In writing for the Blake lesson, some children went backward in the history of English poetry to an earlier style of talking to nature, lamenting mortality and whimsically inquiring into origins. “Rose, where did you get that red?” and “Oh Daffodil I hope you never die but live forever!” showed me a connection I had never thought of and showed me, too, that my students might find it interesting to read Herrick.

The usual criteria for choosing poems to teach children are mistaken, if one wants poetry to be more than a singsong sort of Muzak in the background of their elementary education. It can be so much more. These criteria are total understandability, which stunts children’s poetic education by giving them nothing to understand they have not already understood; “childlikeness” of theme and treatment, which condescends to their feelings and to their intelligence; and “familiarity,” which obliges them to go on reading the same inappropriate poems their parents and grandparents had to read, such as “Thanatopsis” and “The Vision of Sir Launfal.”

One aspect of “childlikeness” which is particularly likely to work against children’s loving poetry and taking it seriously is a cloyingly sweet and trouble-free view of life. Even Blake’s “The Lamb,” alone or in context with other sweet poems, could be taken that way. Constant sweetness is probably the main thing that makes boys, by the time they are in fifth or sixth grade, dislike poetry as something sissified and silly.

I ended up teaching, in the first series of lessons, three twentieth-century poets who wrote in English and one who wrote in Spanish; two poets whom I suppose could be called Romantic—Blake and Whitman—one English, one American; two seventeenth-century poets; and Shakespeare. There was nothing of a survey about what I did. My point was to introduce my students to a variety of poetic experiences. Other teachers will doubtless want to try other poems. There are many poems children can learn from, and a teacher has a pleasantly wide choice.

III

When I became interested in teaching a particular poem, I would look for a poetry idea to go with it, such as, for the Blake class, “Imagine you are talking to a mysterious and beautiful creature and you can speak its secret language, and you can ask it anything you want.” The poetry idea, as I’ve said, was to give the students a way to experience, while writing, some of the main ideas and feelings in the poem we were studying.

Usually one of the same features that attracted me to a poem as a good one to teach would furnish me with the start of the poetry idea. The poetry idea for Herrick’s “Argument” would obviously include “Make a list of things you’ve written poems about”; that for Stevens would begin, “Talk about the same thing in a number of different ways.” The poetry idea for Whitman would have something to do with secrets. That for Shakespeare, with noises; for Lorca, with colors; for Ashbery, with the names of rivers. The poetry idea would also have to connect the poem to the children’s feelings and include suggestions for a form in which they would enjoy writing. So I would work out and elaborate my first conception for a poetry idea until I could give it to the children in a way that would immediately make it interesting and make them eager to write.

Some poems presented no problem. Once the children saw what they were about, they were eager to write poems like them of their own. This was the case with “This Is Just to Say.” Apologizing for something they were secretly glad they had done was so familiar and amusing an experience that in order to inspire them to write about it I had only to show them what the poem was about. Ashbery’s river poem had an equally obvious and immediate appeal just as it was, a poem with a different river in every line. In this case, however, I was a little afraid of a merely mechanical response, so I said, “Write a poem with a river in every line, and really imagine you are seeing the river or are floating on it, and say how it really looks and feels. If you want to, put in colors and sounds and times of year. Think what color each river is, what kind of sound it makes, what month of the year it reminds you of.” Ashbery’s poem doesn’t include such details about each river, but thinking about such details helped the children go from one real, sensuous experience of a river to another—“Delaware—green with April birds and flowers / Missouri—red January bugs and laughter…” (Mayra Morales, 5).

Herrick’s poem, like Ashbery’s, had something immediately appealing for the children to imitate: a list of subjects they had written poems about. However, to enjoy making such a list, as Herrick evidently did, a child would have to be in a similarly pleasantly expansive and satisfied state of mind. I could help to make children feel this way by reminding them of the poems they had written for me about colors, noises, wishes, lies, and dreams. I could suggest that they think, too, of their poems in more detail. Had they written, as Herrick says he has, of flowers? of girls? of love? of things to eat and drink? That was good as far as it went, but some of the children had written only a very few poems. To help them out, and to give to everyone’s poem more of the impetus of pleasure and desire, I made it part of the poetry idea that, along with writing of what they had already written about, they could say what they would like to write about in the future. This makes the poem more exciting.

Williams’s “Between Walls” had an appealing idea—something supposed to be ugly which really is beautiful—but the children would get more out of it if I could connect it to their feelings as well. I did that by using the words really and secretly, which I found as helpful here as, in other lessons, appealing to the children’s senses and asking them to think of colors and sounds. My suggestion was, “Write a poem about something that is supposed to be ugly, but which you really secretly think is beautiful, as Williams thinks the broken glass shining in back of the hospital is beautiful.” Secret was also a help in the Blake class, when, to make the children believe more in the reality of the situation (their talking to an animal or other creature), I said that they should pretend they could speak its secret language.

I saw right away that Shakespeare’s “Come Unto These Yellow Sands” was attractive to children for its gaiety and for its use of sounds, but I didn’t find a way to connect it to their feelings until I began to think about its being an invitation and how exciting the situations of inviting and being invited are for children. Invitations are connected with birthdays and all sorts of mysteries and surprises. My poetry idea, which helped the children get the genuine strangeness of this and other Shakespearean songs, was to write a poem inviting people to a strange and beautiful place, full of wonderful sounds.

Sometimes my students’ reactions would lead me to change the poetry idea. In the Blake class my poetry idea was to ask a creature questions. Several children asked me if they could put in the answers too. I said yes. Though including answers would make a poem less like Blake’s on the surface, it could make it more like his in a more important way if it helped the child believe in the human/animal conversation. Conversations are easier to believe in if someone answers. Another question in the Blake class was “Can we talk to a different creature in every line?” I agreed to this, too. It would make the poem easier for those children who that day didn’t feel up to sustaining a whole poem about one animal, bird, or insect and might help them refresh their inspiration in every line. And Blake himself had addressed a number of different creatures in Songs of Innocence and Experience.

These variations of the poetry ideas weren’t false to the poems except in insignificant ways. I didn’t want a poetry idea which commanded a child to imitate an adult poem closely. That would be pointless. I wanted my students to find and to re-create in themselves the main feelings of the adult poems. For this purpose, a lot of freedom in the poetry idea was necessary. They would need to be free, too, from demands of rhyme and meter, which at their age are restrictions on the imagination; and from the kinds of tone and subject matter which might oppress them. In relation to “The Tyger,” this meant suggesting they write a poem in the form of repeated questions rather than asking for five stanzas of couplet-rhymed tetrameter; and that they write about talking to a strange creature, rather than that they write about The Wonder of God’s Creation.

I could be fairly sure I had a good poetry idea worked out when examples of lines to illustrate it came easily to me. If I could think of lines inviting people to strange places or of ugly things that are really beautiful or of comparisons between geometry and magnetism and how I felt about someone, the children, with my help, would be able to as well. The final test of the idea, though, would be in class—if my suggestions for a poem weren’t exciting and clear to the children, then I would have to find a way to make them so.

There are, of course, different writing suggestions, different poetry ideas that one can use with a particular poem. I approached the wonder and amazement in Blake through the theme of talking to an animal. My own childhood had been colored by the fantastic hope that I would be able to speak to animals and birds and share my feelings with them and find out their secrets, and this was one thing that made me feel my students might respond well to this particular idea. But I could just as well have approached the wonder and amazement through the theme of origins, of thinking of all the strange things in the world and imagining how they were made. Or by the theme of marveling at the superpowered being who does everything that is done in the world. In such a poem, for example, each line might begin with “Who would dare…?” and the children could be helped to begin by a few examples like “Who would dare to make a tiger?”: Who would dare to lift the red-hot sun out of the street every morning? Who would dare to push the electricity through the subway tracks? Who would dare to go out into the middle of the ocean and push the waves to shore?

Writing suggestions have been used with teaching poetry before. Those I have seen in textbooks, however, are unhelpful either because they don’t give the child enough (Write a Poem of Your Own about a Tiger), or because they give him too much—often, for example, telling him what to feel (Write a Poem about How Beautiful You Think Some Animal Is). “Write a Poem in Which You Imagine Talking to an Animal” is in the right direction, but not dramatic enough. A writing suggestion should help a child to feel excited and to think of things he wants to write.

IV

I would go to my classes at PS 61 with copies of poems for everyone. I would pass them out and ask the children to read them. I would tell the children that I would explain what was unclear to them and that after talked about the adult poetry they would write poetry of their own that was like it in some way. Interested, as they always were, in anything connected with their writing, my students read the work to themselves, then listened to me read it aloud, and our discussion began.

When I talked about the poems, I tried to make the children feel close to them in every way I could. The fact that they were going to write a poem connected to the one we studied was a start. Beyond that, I wanted to make the poem as understandable as possible, and also as real, tangible, and dramatic as I could. I wanted to create excitement about it there in the classroom. When I could judge from what the children said and from their mood in general that they had understood the poem and its connection to themselves and to things they wanted to say themselves, I would have them write.

Many details of adult poetry are difficult for children, but they are glad to have them explained if they are interested in the poem, and if they aren’t made to feel that the poem is over their heads. I immediately made the dramatic situation of the poem clear, often by a few questions. Who is Blake talking to? Why does he think that the tiger is “burning”? I responded in a positive way to all their answers; even wrong answers would show them thinking about the poem and using their ingenuity, trying to understand. Once started on that path, with my help and that of their classmates, they eventually understood. As soon as I could, I would begin to associate the poem with their own experience. Have you ever talked with a cat or a dog? Have you ever seen its eyes in the dark? Did they shine like those of the tiger? Unfamiliar words, such as fearful and frame, and odd syntactical constructions, such as “What dread hand? and what dread feet?” I treated as small impediments in the way of enjoying the big experience of the poem, to be dealt with as quickly as possible. I explained them briefly and went on.

Along with doing all I could to make the poem available and easy, I did things in every class to dramatize the poem and make the children excited about it. When we came to Blake’s lines about the creation of the tiger’s heart, “And what shoulder, and what art / Could twist the sinews of thy heart?” I asked the children to close their eyes, be quiet, put their fingers in their ears, and listen hard: that strange, muffled thumping they heard was their heart—how must Blake have felt imagining the tiger’s heart, which was probably even stranger?

To dramatize Donne’s compass image and show the children how it really worked, I brought a big compass to school and showed them what his comparison was about in every detail. In the Lorca class, to help them feel the music and the magical use of colors, I had the children close their eyes and listen while I said words in English and in Spanish, such as “green” and “verde,” and asked questions such as “Which word is greener? Which is brighter?” To excite the children about William’s “The Locust Tree in Flower,” I began by having the whole class write a poem like it together, the children shouting out lines to me, which I wrote on the blackboard. In the Ashbery class I had the children call out to me the names of all the rivers they could think of. In the Herrick class, they named the things they had written about and the things they wanted to write about.

The discussion of some poems went more quickly than that of others. The discussion of the Williams poems, for example, was very brief. After a few readings and a few questions, the children seemed really to have a sense of the poems and to be ready to write. They were starting their own poems five minutes after the class began. I spent a good deal more time discussing “The Tyger.” I wanted to be sure to communicate to the children the main feelings in the poem—fear, amazement, and wonder—which seemed less accessible to them than the main feelings in “Between Walls” and “This Is Just to Say.” It seemed good to linger over particular parts of the poem to make them dramatic and real—the tiger’s burning, the forests of the night, the fire in the tiger’s eyes, the making of the tiger’s brain in a furnace. Even my explanation of symmetry, a word none of my students knew, helped to involve them in the poem. I showed them that they themselves were symmetrical, and—excitedly touching their own shoulders, elbows, ears, and knees—they could feel the strangeness of the tiger’s symmetry, too. I didn’t think it necessary to teach every detail of a poem, just those that would help give the children a true sense of its main feelings.

Once they had that sense, I would give them the poetry idea; sometimes I would have given them a suggestion of it earlier in the lesson, so they could think about it while going over the poem. Now I had to make sure that it was clear enough to help them write a poem. First I would explain the idea, then answer questions about it; then give the children a few examples of how it would work out, what kinds of subjects they might deal with, what kinds of lines they might write. When I had suggested a few possibilities, like “You can compare you and your girlfriend or boyfriend to magnets,” or “You can ask questions like ‘Lion, where did your terrible roar come from?,’ ” I would ask the children for ideas and sample lines of their own. When these came to them easily, and when a lot of hands were raised in the air to give me more and more of them, that is, when the children were obviously understanding the project and full of ideas, I would pass out paper and they would write.

This writing part of the lesson was the same as it had been in my classes on teaching poetry writing alone, without adult poetry. The children talked, laughed, looked at each other’s poems, called me to their desks to read and to admire, or, if they were “stuck,” to give them ideas. It was a happy, competitive, creative atmosphere, and I was there to praise them, encourage them, and inspire them. When a student finished a poem quickly, I would sometimes suggest he write another. Some sixth graders were so excited about Williams’s “This Is Just to Say” that they rapidly wrote three or four poems, apologizing to their dog, their fish, their parents, and their friends—to the dog, perhaps, for eating its biscuit, to the fish for forgetting to feed it, to their mother for breaking a dish, to a friend for eating the flowers off his head.

In the Lorca class, if they had finished quickly, I asked those children who had written their poems all in Spanish to take another sheet of paper and write a translation. Sometimes when a child felt seriously impeded, I’d suggest he write a poem in collaboration with somebody else, or I would write one with him myself, which is how Rosa Rosario and I wrote “Poem: At six o’clock….” My aim in general was to move around enough and respond enough to what the children were writing to keep things going happily all over the room.

I wanted to keep the free and pleasant atmosphere my students had always had in which to write poetry. There was no reason why the presence of great poems should interfere with that. I did everything I could in our discussion to make the poem seem easy and familiar to them. Now, while they wrote, I let the poetry idea take over from the adult poem, and their own ideas lead them in various directions. In the Blake class: Yes, you can talk to a stone if you wish, instead of an animal. Yes, Markus, you can write it in “octopus language.” Yes, you can, instead of asking the animal questions, tell it what to do. I would stress, all the while, the part of it I thought would most inspire them: But remember, whatever you do, that you are really talking to it—really. I said yes, too, to my Spanish-speaking students, in the Lorca class, who wanted to write their whole poems in Spanish instead of just using Spanish words for colors. And to Yuk, a Chinese girl in the same fifth-grade class, who asked if, instead of Spanish words, she could use Chinese color words in her poem.

When I praised the children’s lines, it was not for their resemblance to Blake or to Donne, but for what they were in themselves—sometimes very much like the work of the poet we started with and sometimes less so—

Giraffe! Giraffe!

What kicky, sticky legs you’ve got.

What a long neck you’ve got. It looks like a stick of fire….

—Hipolito Rivera, 6

The adult poem started them off, but this part was all their own, and had to be. Otherwise the lesson would come to nothing. Forced imitation could make them hate the adult poem rather than like it and wouldn’t bring them close to it. But the energy and volatility of their imagination were a different kind of educational force. Anything the poem started in their imagination, and wherever it took them I thought was fine.

To help them be free as they wrote, I urged them to write mainly in their own language rather than in that of the poem if it was from an earlier time. Rhyme, as I have said, I told them they needn’t use. And, as in all my poetry classes, I asked them not to worry about spelling (or punctuation or neatness). All that could be corrected later. De-emphasizing these mechanical aspects of writing makes it easier for everyone to write and makes it possible thereby for some children who would not otherwise have dared to write poetry to write it and to come to love it; I had children like this, in fact, terrible spellers, who developed into fine and enthusiastic poets, and into students with more confidence in themselves as well.

The children usually wrote for about fifteen minutes. I tried to give everybody time to finish, though if one or two children were still writing after everyone else was waiting to give me his poem, I collected all but theirs and let them go on writing. Sometimes I would read the poems aloud to the class. More often the children would read them themselves—they had come to enjoy doing that quite a lot. Afterward I would mimeograph their poems and include among them the adult work we had studied. Blake’s “The Tyger” would be there between Loraine Fedison’s “Oh Ants Oh Ants” and Hipolito Rivera’s “Giraffe! Giraffe!” and, I felt pretty sure, somewhere in everyone’s memory and imagination as a real and vivid experience.

To help children write well and enjoy it, perhaps the most important thing to do, I found, is to be positive about everything. I responded appreciatively to what they said and to what they wrote. Everything had some value, the very fact they could imagine talking to an animal, anything at all they found to say to it. So encouraged, they could go on to do more. Poetry writing is a talent that thrives, in children at any rate, on responsiveness and praise. If I preferred some lines or ideas to others, I responded more enthusiastically to those, rather than criticizing the ones I liked less.

V

I was assured the children were learning something by their continuing interest in class and by the poems they wrote. Sometimes a child wrote a poem that showed a remarkable mastery of a particular poet’s way of seeing and experiencing things—

Goldglass

In the backyard

Lies in the sun

White glass

Reflecting the sun

—Marion Mackles, 6

Marion’s poem, written in a class on William Carlos Williams, shows not only Williams’s attention to the beauty of small and supposedly unbeautiful things, but also his way of making the poem, as it goes along, a physical experience of discovery for the reader. Sometimes what the children wrote would be in many ways unlike the adult poetry we read, yet obviously inspired by it, as were a number of poems written in the Shakespeare class, poems about escaping into freedom: freedom from school; freedom from the powerlessness of childhood; freedom, even, from ordinary reality—

Oh come with me to see a Daisy….

And put a lion on the chair and let teacher sit on it…

…and let her give no homework for the rest of the year….

—Andrea Dockery, 5

We’ll fly away, over mountains and hills.

And then for us the world will stand still.

The world will be at our command….

—Maria Gutierrez, 5

We are free, free, come, come, I am inviting you to the land of freedom where dogs go quack quack instead of bow, wow, bark, bark….

—Rosa Rosario, 5

Of course, I didn’t give quizzes or tests of any kind on poetry. A few bad marks would have made poetry, for most of my students, an enemy. But though few had the critical skill to say much about the poems we read, they all could experience them. For the space of reading the Blake poems and writing Blake-like poems of their own, the children were confronting tigers; they were talking to nature; they were lifted out of their ordinary selves by the magic of what they were saying, the fresh power of their feelings and perceptions was, for a moment, a real power in the world.

One may feel, as a poet I know said to me, that “some things should be saved for later.” Some things inevitably will be, because there are aspects of Blake’s “The Tyger” and Donne’s “Valediction” which elementary-school children won’t respond to. But to save the whole poems for later means that some important things will be lost, permanently—the experience, for example, of responding to Blake’s poem when one is ten years old and can still half believe that one’s girlfriend was created by a magical transformation and that one can talk to a lion about its speed and its strength; or the experience of “Come Unto These Yellow Sands,” when one can believe in the magic of dancing oneself into oneness with nature; or reading John Donne when rocketry and desire can be thought of together in an unaffected way.

All these are good experiences to have. When a child has had a few of them, he may begin to anticipate finding more of them in poetry and want to read more of it, rather than being cut off from it, as so many schoolchildren now are. My students, of course, were also being helped as writers. The adult poems added good things to their own work. When they picked up their pencils to write, there were new tones they could take, more ways to organize a poem, new kinds of subject matter they could bring in.

Different children did their best work at different times. A few young poets suddenly came to life in the class on William Carlos Williams’s “This Is Just to Say”; I suspect it was the naughtiness theme (apologizing but really glad) that did it. Some Spanish-speaking students wrote their best work in the Lorca class, obviously delighted at the chance to read a poem in school in their language and to be able to use Spanish in their own poems. Some classes were altogether better than others. The children’s responses to Blake and Donne were especially strong and convincing, whereas I felt my students had not gotten as much as they might have from Stevens. I thought of a better way to teach Stevens only afterward.4

Sometimes even with the best of poems and poetry ideas, a poetry class would go badly; the children would be tired or out of sorts, or I would be, and the enthusiasm and excitement conducive to writing poems wouldn’t be there. Sometimes a class would start badly but pick up suddenly after some student or I had a good idea. In any case, a dull or difficult class doesn’t mean that children “aren’t really interested” in poetry, but only that something is interfering with their feeling that interest as strongly as they might.

The differences between grades were like those I had already noticed in teaching writing. Third- and fourth-graders tended to be more exuberant, bouncy, and buoyant than their more serious older schoolmates. One of their characteristic reactions was to write “joke poems,” which made fun of some aspect of the poem or of my poetry idea: of talking to an animal in its secret language, for example, in the lesson on Blake—“Glub blub, little squid. Glub blub, why blub do you glub have blub glubblub blub such glub inky stuff blubbb…?” (Markus Niebanck)—or in the same lesson, of the strangeness of creatures—“Little duck, little duck, how did you get those iron legs? / How did you get those steel eyes…?” (Edgar Guadeloupe).

These were fine responses to the poems and I showed my appreciation of them. Wildness and craziness and silliness were means for all my students to make contact with their own imaginations and through them with the adult poems, and they were especially important to the seven-to-nine-year-olds. The fifth-and sixth-graders were usually somewhat more responsive to the texture and detail of the poems, or at least better able to transfer certain qualities of phrasing and tone to their own work, as in these lines from the sixth-grade Blake poems: “Oh butterfly oh butterfly / Where did you get your burning red wings?…” (Lisa Smalley); “When the stars fall to the earth and the purple moon comes out no more…” (Andrew Vecchione). Third-and fourth-graders, however, showed they were quite able to get the essentials: “Oh, you must come from a hairy god!…” (from “Monkey” by Michelle Woods); “…Ant, the most precious, where did you get your body? / Beautiful butterfly, where did you get your wings?…” (Arlene Wong).

One thing I think all of my classes profited from was the fact that the children had written a number of their own poems before, independently of the study of the adult works. Some had as many as twenty classes in writing poetry, some only five or six. All had enough to make them feel like poets, however, and this was a great help to them in reading what other poets had written. They were close to poetry because it was something they created themselves. Adult poetry wasn’t so strange to them; they could come to it to some degree as equals.

A good teacher can bring poetry close to children anyway, but their already feeling easy and happy about it is a real advantage. When they took up their pencils to write works inspired by Blake, Donne, and the other poets, they already knew what it was like to write poetry. They had experience of using comparisons, noises, colors, dream materials, wishes, lies, and so on. This gave them a better chance to create something original in the presence of the adult poems, which might otherwise have been simply too intimidating. I suggest beginning the teaching of poetry with writing alone; then, after five or six lessons, introducing such adult poems as the children seem ready for. In these first classes a teacher can get a sense of what children like about poetry and how best to help them to write and to enjoy it.

In the first few lessons using adult poetry, it may be good to bring it in mainly as an inspiration for the children’s own work—that is, not discussing the adult poem at all, but merely using it as an example—as I did with the poems by Lawrence and Ashbery. In this way the children can get accustomed to a free and easy relationship with it. One may decide, too, to alternate the classes using adult poetry with some sessions of only writing. The important thing is to keep the atmosphere free, airy, and creative, never weighed down by the adult poems. Once they are too grand and remote, their grandeur and remoteness will be all they communicate; and children, in the classroom as elsewhere, thrive on familiarity, nearness, and affection, and on being able to do something themselves. What matters for the present is not that the children admire Blake and his achievement, but that each child be able to find a tyger of his own.

Of course they can learn more about poetry later, and they will do it better for having read poetry this way now. Even beginning this kind of study in high school, it is not too late to establish the necessary relation between what is in the poems and what is in the student’s own mind and feelings and in his capacity to create for himself. There are, of course, special problems with adolescent students—shyness, literariness of some who write, aggression and contempt of some who won’t—but a teacher who knows students that age and can be enthusiastic and at the same time free and easy with them about poetry should be able to teach it very well.

There are some extensions and embellishments of this way of teaching that can be tried in elementary school—spending a few weeks on Blake, for example, with every student writing several poems in some way suggested by him and putting together a book of them with illustrations, like Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience; or reading a number of poems which talk to nature in different ways; or reading the work of different poets who lived at the same time. The thing to aim for always, however, is the individual student responding to the individual poem in his own way.

PS 61 was not the only place poetry was taught this way. I corresponded with a few teachers elsewhere whom I knew to be teaching writing, and asked them to try out Blake or Stevens or Shakespeare on their classes. I received poems from schools in Providence and New Orleans and others from a missionary school in Swaziland, in Africa, where an American Peace Corps worker was teaching poetry to ninth-grade students. I also taught a few classes in secondary schools, including the Lycée Français in New York. The poems from all these schools show what the students found in the adult poems with the help of the discussion and of the poetry idea, and what they were able to do with what they found. The results of any combination of teacher, children, and adult poetry are not predictable. What the children write will vary according to all three, but a good and enthusiastic response to the adult poems does seem a common factor of all these works by children of different ages, in different schools, with different teachers, and even, in the case of the Swazi poems, from different cultures.

BIRDS

Mr. Robin, how did you ever get those beautiful red, yellow, blue

feathers?

Long ago Indians gave me the feathers from their heads.Dear Mr. Bluejay, where did you get those beautiful eyes of yours?

They came from the sky of yours.Bluebird, why were you named Bluebird? Please answer.

I got the name from an ancient god over ten thousand years ago.Mr. Tiger, where did you get your beautiful skin?

I guess I got it from blowing wind.

—Rosa Rosario, 5Come with me to the world of secrets.

Do you know how a mind grows? I do. If you don’t, you won’t find it on a piece of paper, you’ll find it on the dark blue sky.

Do you know how to get to the end of the universe? I do. If you don’t, you won’t find it in the almanac, you’ll find it in the number nine.

Do you know where fish came from? I do. If you don’t, you won’t find it in a book about fish, you’ll find it on the earth’s equator.

—Lisa Smalley, 6Hatred is like a pen drawing two lines far apart, and when they get to know each other, the pen connects them.

Fear is like the lines never connecting.

Love is like they were never apart.

Like is when they are a fourth of an inch apart.

—Bill Constant, 6A space capsule is like a man with two wives.

One part falls off because she finds out about the other wife.

The second part falls off when they get divorced and the third falls off when the man dies, and the lunar module floats to heaven like his soul.

—Andrew Vecchione, 6Oh Rose, where did you get your color?

Dog so beautiful, how do you learn how to bark? Will you teach me?

Ant, the most precious, where did you get your body?

Beautiful butterfly, where did you get your wings?Rose: there once was a red sea and I fell in.

Dog: my mother gave me lessons.

Ant: three rocks were stuck together, then lightning hit me.

Butterfly: one day a kid in Mrs. Fay’s class drew a butterfly, then it

got loose and it was raining, then it was alive the next day.

—Arlene Wong, 3-4

THE LOVE COMPARISON

Two people in love are like two rockets blasting off to the same planet.

Two people in love are like the two of them floating free of gravity.

Two people in love are like light against light, all becoming as one.

Two people in love are like two stars put together turning into one

planet.Love is like thunder and lightning going through one planet.

Love is like two planets turning into the size of stars, then becoming as one.

—Arnaldo Gomez, 6

THE LION

Oh, Majesty Lion, saluted I.

Who made you to be the king of animals?

Who made your eyes as fearful as the burning fires of the Usuthu

forests?Even your paws are as dangerous as the robbers at night.

Your voice is so big as thunderstorms in the hot summer seasons.

Who made your tail so fluffy that even flies don’t touch it?

Who made you so fearful that even the creatures of the world are

afraid of you?

—Author Unknown, Swaziland, 9

RIVERS

The Rhine River is red paint rushing down the rocks in Russia.

I see myself in a raft on the Don River hitting the rocks coming downstream.

There I can see below the top rocks the soft silent water swaying back and forth against the rocks.

The Yukon River with its light blue water rushes and roughs its water in the day and softens in the evening.

I can see the Amazon River with its violet water brushing at my face

and it feels so cool and creamy like I could stay there forever.

The Yangtze River is yellow with pretty glowing white rocks in the early morning and the empty bridge is strong and healthy.

—Ilona Baburka, 5

FORGIVE ME CHICKEN

Forgive me chicken

For taking your

Eggs but they

Taste so good.

—Tommy Kennedy, 6

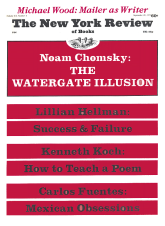

This Issue

September 20, 1973

-

*

See “Wishes, Lies, and Dreams: Teaching Children to Write Poetry,” NYR, April 9, 1970. Published in book form by Random House.

↩ -

1

Here as elsewhere in this article, the number following the child’s name indicates the grade he or she was in when the poem was written.

↩ -

2

From “September,” The World of Language, Book 5 (Follett Educational Corporation).

↩ -

3

“A Famous Author Speaks,” Our Language Today (American Book Company).

↩ -

4

Usually when I had ideas for improving a lesson, I’d have a chance to try it again. Often, when I taught two or three different classes (of different children) in succession, the later ones would profit from what I’d learned in the earlier.

↩