In response to:

The Good Old Days from the June 14, 1973 issue

To the Editors:

“The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia is equal in authority to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.”

Mr. Steel is rightly indignant for being reminded of the discovery he made six years ago. His defense is curious—he was quoted out of context, for did he not add the words “over all questions which do not involve the security of the Soviet state”?

Either Mr. Steel does not know that everything of political, cultural, social, and economic importance that happens in Czechoslovakia involves the security of the Soviet state as the Soviet leaders interpret it, in which case he has no business to write about international affairs. Or he did know it, and deliberately misled his readers. There could be, however, a third, less Machiavellian explanation which I may have overlooked—that he was not aware then, and is not aware even now, that he wrote nonsense.

My apologies to Mr. Steel.

Walter Laqueur

Ronald Steel replies:

Mr. Maddox is correct in concluding that I did not look favorably upon his book. The reasons, however, are not that I was hostile to a critique of the so-called “New Left,” for in my review I amply observed that “revisionists have sometimes been inaccurate in their use of source material and unduly eager to jump at predetermined conclusions” some of which “seem to be based as much upon supposition and inference as upon incontrovertible evidence.” Rather, my objection to Mr. Maddox’s book is that he has failed to produce the serious, analytical, documented questioning of revisionist interpretations that is long overdue. Instead he has relied on innuendo, distortion, and partial quotation to undermine revisionist thesis, and has succeeded only in showing that his own interpretations of the evidence are just as questionable as those he attacks. Above all, he has conspicuously failed to address himself to the central issue that the revisionists—whether or not one agrees with their interpretation of the evidence—have confronted directly: the motivation of American policy-makers. It is about time that we dealt with these broader issues rather than nit-picking over what tone of voice Truman used to Molotov.

My complaint with Mr. Maddox is not that he attacks the revisionists, but that he duplicates their worst faults—using evidence selectively to sustain a predetermined thesis—without even dealing with their major premise: that US foreign policy is comprehensible only in terms of the role that American leaders believed the nation must play in the postwar world. To imply, as Mr. Maddox does, that a portrait tells a lie because the artist exaggerates some details and leaves out others is to miss the point.

As far as his specific objections to my review are concerned, Mr. Maddox knows very well that only a very small part of my criticism was rooted in the memoranda circulated by the revisionists he attacked. And in the two cases where I did so—Gardner and Kolko—I indicated that these were refutations by the authors concerned. My criticism of his discussion of Alperovitz, to take one example, covered considerably more space than the other direct refutations combined, and this certainly did not come from the author.

As for my observation that Mr. Maddox fails to make his case against Lloyd Gardner, one has only to read his chapter on Architects of Illusion and compare it with the original to realize that Mr. Maddox, whether deliberately or not, misconstrued Gardner’s argument. Having misrepresented Gardner’s thesis and selectively misquoted him, Mr. Maddox then goes on to take him to task for not proving what he, in fact, never postulated. Unfortunately, Mr. Maddox does indeed offer no sustained criticism, and one is left with the conclusion that while Gardner may or may not have misinterpreted the evidence, Maddox has certainly misinterpreted Gardner.

Mr. Maddox claims I am “dead wrong” on two matters. First, that I charge him with assuming that there is such a single thing as a New Left point of view. True Mr. Maddox did write that “revisionists disagree among themselves on a wide range of specific issues.” But, master of the selective quote that he is, he does not include the rest of that sentence, which includes, “they tend to divide into two recognizable groups.” These two groups, “hard” and “soft” revisionists, become virtually indistinguishable throughout his book, despite the mild disclaimer in the introduction. By page 7 the distinction between them has disappeared, for we are told that “revisionists almost always employ a double standard,” and on page 8 that “New Left authors exaggerate the importance of evidence which supports their themes,” and on page 10 that “New Left authors have revised evidence itself.” Not some “New Left” authors, mind you, or even the seven he has singled out for attack, but the so-called “New Left” in general. If Mr. Maddox does not assume that there is a single New Left point of view, why does he begin chapter 2 with the flat assertion that “Pinning labels on historians is a hazardous enterprise at best, but in general terms ‘New Left’ and ‘revisionist’ are synonymous when applied to interpretations of how the Cold War began.” Mr. Maddox may indeed realize that the revisionists often disagree wildly among themselves and that the search for a New Left “line” is an exercise in futility. But if so, he gives little evidence of this in his intemperate and unconvincing assault upon the historians with whom he disagrees.

Second, he is astounded that I should have thought that he was trying to prove not only distortion on the part of New Left historians, but collusion and conspiracy as well. Yet how else is one to construe his statement on page 161 that reviewers give favorable notices to some revisionist texts only because a) they themselves are ignorant of the distortions made, or b) “The second possibility—far more intriguing—is that reviewers who were perfectly aware of the procedures employed nevertheless concluded that it was unnecessary to share this information with their readers. Their motives, like those of the revisionists themselves, can only be surmised.”

Mr. Maddox’s motives, too, in writing this kind of attack can only be surmised. But if he did not mean to suggest collusion and conspiracy among the “New Left” historians and reviewers, he has certainly chosen a curious way to express himself.

As far as Mr. Laqueur is concerned, I accept his apologies for using half a quotation and thus distorting my meaning, and respectfully suggest that there is a fourth possibility: that the Soviets tolerated a considerable degree of cultural, social, and even political nonconformity in Czechoslovakia during, and even preceding, the famous “Prague spring” and that they intervened with brutal military force when they felt—like Lyndon Johnson in the Dominican Republic—that their satellite was about to slip out of their camp and thus pose a potential threat to their security. Surely a man of Mr. Laqueur’s demonstrated acumen should not find that so hard to concede. It is really the courageous Czechs, inside and outside the party, who prepared the way for the events of 1968 to whom Mr. Laqueur owes an apology; for he seems unaware that they existed, or, indeed, could have existed, during the 1960s.

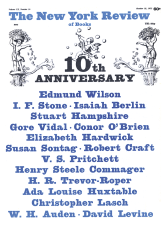

This Issue

October 18, 1973