—Washington

Before Congress approves Agnew’s successor, it ought to find out what commitments he may have made to protect Mr. Nixon from the law when the latter leaves office.

Everybody has been asking whether, in choosing a successor, Mr. Nixon would be swayed by the good of the country or the good of the Republican party. An altogether different consideration may outweigh either, and that is the good of Richard Nixon as the central figure in several ongoing criminal investigations, among them Watergate, the Ellsberg break-in, and the ITT affair.

The good of the country called for a caretaker nomination of unimpeachable character—how the phrase has changed overnight from a cliché to a painful need! The good of the Republican party called for an appointee who could be built up into a winning candidate by 1976. But Mr. Nixon’s own interest is in a successor he can count on to use all the powers of the Presidency to protect him in any litigation or prosecution after Nixon leaves office. To put it plainly, Mr. Nixon needs to make sure that his successor will not treat him as he treated Agnew—as expendable.

There are at least three spheres in which the presidential powers of his successor can be exercised to Mr. Nixon’s benefit. One is that of the tapes.

Let us suppose that the Supreme Court eventually upholds the subpoenas of Special Prosecutor Cox or the Ervin Committee, or both, and that Mr. Nixon refuses to hand the tapes over on the excuse that the decision is not “definitive,” a word for which the Chief Executive refuses to supply a “definitive” definition.

These tapes are the property not of Mr. Nixon personally but of the White House. Their confidentiality, if any, is a function of the office and not of the man. When he leaves the White House, will his successor keep the tapes in custody or turn them over?

Mr. Nixon can decline to hand over the tapes even on trial by impeachment. Should he be removed by impeachment or resign or serve out his term he might still be prosecuted afterward for conspiracy to obstruct justice or for some other crime. Such prosecution might be facilitated if his successor decided that the Supreme Court had to be obeyed, and handed over the tapes.

The two other areas in which the new appointee could protect Mr. Nixon when he leaves office lie in the President’s power as the country’s chief law-enforcement officer and in his power of pardon. The former includes his control not only over the Department of Justice but also over the Internal Revenue Service. The latter is important because of the unexplained questions about Mr. Nixon’s income taxes and the public funds expended on his private homes.

Mr. Nixon’s view of these extensive powers can only be described as crass. This has just come to light in the Memorandum of Law which his solicitor general filed on October 5 with Judge Hoffman. This disputed the Vice President’s claim that his office gave him constitutional immunity from prosecution for any crime unless first impeached and removed from office. Agnew’s claim in this was exactly the same as Nixon’s. The solicitor general had to walk the tight rope of rebutting the Vice President’s argument without impairing the President’s.

This called for quite a feat. There is nothing in the Constitution or in the debates of the Framers and of the ratifying Conventions that draws any distinction whatsoever between the two offices in this respect or indeed between the President’s position and that of any other civil officer, including federal judges, several of whom have been convicted of crimes without first being impeached. The solicitor general did not cite a single specific authority for any such distinction.

What the solicitor general had to fall back upon can only be described as a naked cynicism. This finally appears as the culmination of a tortuous and tortured argument on page 20 of the twenty-three-page memorandum. Here is what it says:

The Framers could not have contemplated prosecution of an incumbent President because they vested in him complete power over the execution of the laws, which includes, of course, the power to control prosecutions. And they gave him “Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offenses against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment,” a power that is consistent only with the conclusion that the President must be removed by impeachment and so deprived of the power to pardon, before criminal process can be instituted against him. A Vice President, of course, has no power either to control prosecutions or to grant pardons.

What this says, in other words, is that it is impossible in practice to prosecute a President for any crime he commits in office because he controls the prosecuting agency, the Department of Justice, and even if convicted could pardon himself. This fits the Nixonian jurisprudence perfectly, but it misreads the letter and the spirit of the Constitution.

Advertisement

Article II, section 1, does not simply give the President “power to control prosecutions.” What it says is that “he [the President] shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed” (our italics). To use his power to prevent prosecution when he himself was accused would hardly be the faithful execution of the laws. Nor was “Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons” ever intended to be used by some future Chief Executive to pardon himself.

Three pages earlier the Memorandum of Law, in spelling out the awesome array of powers wielded by the President, included those of the commander in chief. The solicitor general might just as well have argued that it was impossible to remove a President even by impeachment since he could, if he chose, use his military force to dissolve Congress as Cromwell did Parliament, and rule by degree.

The solicitor general was talking not law but power; he was expounding Machiavelli not Madison. The only difference between the President and the Vice President in this respect is that the former, if he chooses to be unscrupulous, can get away with it. Get away with it, that is, as long as he remains in office and as long as he is firmly supported by his successor. This dictates a choice Nixon can not only control but hope to elect in 1976.

A President whose solicitor general bases his immunity from prosecution on doctrine so repugnant to constitutional government is a President who seems to be afraid of facing the normal processes of trial, as Agnew was when he resigned. Such a man in the White House must strive to be certain his successor will protect him when he leaves office, or at least stand by to pardon him if convicted. Governor Connally has already tried to qualify for the succession in a statement on September 10 launching a national speaking tour. He then declared even more baldly than Nixon that a President has the right to disobey the Supreme Court in such cases as that of the Watergate tapes.

It is the duty of Congress to question Nixon’s nominee about whether he has discussed these contingencies with Nixon and to explore the questions raised by Connally’s statement. Otherwise the new appointment may itself be another—and major—step in a continuing conspiracy to obstruct justice and to found a new line of presidents who like Nixon may feel free to place themselves above the law.

(October 11, 1973)

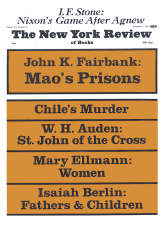

This Issue

November 1, 1973