John Dos Passos died in 1970, and it is startling to find him in our own world, deploring (in a letter to his daughter) “this hysteria about Cambodia” and praising Nixon for “the first rational military step in the whole war” taken “in face of overwhelming Communist-inspired propaganda.” For years it had been much easier not to think about his puzzling case, the conversion of the radical author of Three Soldiers, Manhattan Transfer, and U.S.A. into the anticommunist apologist for America.

The novels were still there, somewhere, of course, and he was still dutifully listed with Hemingway, Faulkner, and Fitzgerald as one of our modern masters who arose in the Twenties to connect us with what was going on in literary Europe. But I doubt that the novels have been much read, outside Modern American Lit. classrooms, for twenty or thirty years. At best you read U.S.A., as I did in the Fifties, because of its interesting and sometimes moving account of a political history you were born too late to take part in, not as a work of great literary distinction.

Professors Townsend Ludington and Melvin Landsberg seem in some doubt themselves about just what it is that they have devoted their impressive scholarly energies to. Landsberg calls U.S.A. “an outstanding and enduring literary achievement” but quickly adds, as if unwilling to argue about it, that it “yet…is biographically significant beyond its literary merit”; Ludington even more cautiously settles for saying that the letters and diaries he has collected “should enhance Dos Passos’ reputation” and help in “assessing his contributions to American literature.” Neither of these books helps directly with Dos Passos’s work—Landsberg’s chapter on U.S.A. contains rather pedestrian criticism, with lots of plot summary and character analysis, while Ludington doesn’t even attempt critical assessment. But Dos Passos was an appealing and interesting person whose life matters at least as much as his work. Both books suggest that the person seems more important than the novels, and make one want to know why.

It always helps a little in trying to understand a writer to know what he looked like, and the older Dos Passos obliged by contriving an amazing resemblance to Dwight D. Eisenhower, from the polished dome down to the big, winning grin—the marriage of Jeffersonian ideals and cold war realism is there to see. But what did the younger Dos Passos look like? On the dust jacket of The Fourteenth Chronicle is a photograph taken in the mid-1920s of Dos Passos sitting on a balcony in some Spanish town, looking smooth, well-groomed, and self-assured, like any young Harvard man with intellectual pretensions and a good family in the background. He looks like a promising young man of letters, that is, whose papers would be handsomely edited fifty years later by a serious scholar like Ludington.

Yet on the dust jacket of Landsberg’s book the photograph of Dos Passos is of someone else with the same name, in a wrinkled suit, hat crumpled in hand, the thin end of the necktie pulled down below the thick end, looking myopic, physically awkward, and a little truculent, striding along at a demonstration for Sacco and Vanzetti. He looks like someone about whom a serious scholar would write a political biography, like Landsberg’s. The other photographs in Landsberg’s book mostly show an unsmiling, bespectacled man, a primly committed, vaguely Jewish radical intellectual, while Ludington’s shows us pictures of a much handsomer fellow, usually smiling and often at play—on the beach with Sara and Gerald Murphy, skiing or fishing with Hemingway, looking distinctly Anglo-Saxon (though slightly Latin).

To be less frivolous about it, both books suggest a corresponding plasticity in Dos Passos’s attitudes and styles, even in his younger days. The letters in The Fourteenth Chronicle show a writer busy with self-invention, trying out personalities in his relations with other people. He evidently didn’t make friends easily (though he was good at keeping them), and he seems often to have been lonely:

Am wandering about the Boulevards in one of those moods of isolation where I seem utterly left out of the gaudy stream of life that throbs and thunders about my ears with a sound of kisses and fighting, a tenseness of muscles taut with love and hate.

It comes, I suppose, of expecting too much of life, of wanting to live more than ever man lived before. There is such an endless welter of experience to untangle, Beauty and misery are so unutterably manifold that there is no time for triviality. The strangest thing of all is how, in spite of the fury of my desires, I seem to remain for ever rigid in the straightjacket of my inhibitions…. M’en fous!

Written in 1919 (he was twenty-three and sounds it) to Walter Rumsey Marvin, a lifelong friend four years his junior, this letter, for all its romantic inflation, seems to reflect strong anxiety about sex and physical manliness (“kisses and fighting”) in his early life. Except for one to his mother and one to E. E. Cummings’s mother, there are no letters to women in Ludington’s collection until 1932, when he began to write occasionally and very tenderly to his first wife, whom he married when he was thirty-three, and the voluminous letters to Marvin are colored with the tones and imagery of a no doubt theoretical and literary homoeroticism.

Advertisement

But then most of the moods of the letters seem abstract and literary in some way. The role-playing is almost endearingly obvious. With Hemingway he became Hemingway:

Honestly—Hem—I think that publication is the honestest and easiest method of getting rid of bum writing—Unpublished stuff just festers and you get to be like a horse that’s pistol shy or whatever they call it when they are wonderful horses but can never start a race…. The thing is that one has got to have people to throw up red flags (like Gammer’s Goat) when one has produced a talented and daintily scented turd—which is the great danger with all us guys.

(March 27, 1927)

With Marvin, somewhat earlier, he played man of the world, pontificating about art and life to a younger and less experienced friend in the idiom of an already dated high culture:

Like you I believe in frugal living, unwasteful—Like you I abhor the puppyish lying about of college life, the basking in the sun with a full belly. Life is too gorgeous to waste a second of it in drabness or open-mouthed stupidity. One must work and riot and throw oneself into the whirl. Boredom and denseness are the two unforgivable sins. We’ll have plenty of time to be bored when the little white worms crawl about our bones in the crescent putrifying earth. While we live we must make the torch burn ever brighter until it flares out in the socket. Let’s have no smelly smouldering.

(December 29, 1918)

But even in the earlier letters these Paterisms, with their dismissal of such grossness as a full belly, clash amusingly with Dos Passos’s other selves. Writing in the same week to Dudley Poore, for example, Dos Passos found different uses for gastronomic metaphors:

Out of the dark that covers me etc I escaped for the day to Sens. I have tasted of the divine one of the movable mansion, I have eaten of escargots—great juicy squirming escargots. Therefore I am strengthened to write one more appeal for news. I don’t care if your mouth and both hands are constantly full of letters, or if you never have a moment in which you are not couriering after something—you must write with your toes or by telepathy or somehow.

Though the style is easier and more visibly playful with someone like Poore, his equal in age and sophistication, one still hears the lonely man’s demand for response, the worry of an ego somewhat smaller than those of most artists that in his absence people may be forgetting about him.

Unable to create a style and tone suitable for all-purpose use, the younger Dos Passos needed the stimulus of other minds and personalities to elicit and direct his own work. He used his friends in this way, and he also used books. “Was ever a creature more dependent on literature for life and stimulus [?],” he asked himself in his diary in 1918, and the letters in their very literariness reflect a range of reading that, except for Joyce, may be unmatched among novelists of this century. Ludington quotes a passage from Dos Passos’s preface to his translation of Blaise Cendrars, which, describing “the creative tidal wave” of European modernism, mentions Apollinaire, Picasso, Modigliani, Marinetti, Chagall, Mayakovsky, Meyerhold, Eisenstein, Joyce, Gertrude Stein, Eliot, Stravinsky, Diaghilev, Rivera, and others; Ludington remarks that the list reads “like a roll call of the people who influenced him.” So it does, and the idea of being open to “influences” on so vast a scale may indicate why U.S.A., for all its breadth of observation and technical resourcefulness, seems to lack a center, a governing idiosyncratic imagination or principle of order within its rather mechanical alternation of narrative, “Newsreel,” autobiography, and brief lives of great modern men.

Still, there are fine things in the novels, moments of acutely perceived human and social detail. The journal passages in The Fourteenth Chronicle unfortunately end after World War I—Ludington explains that the later entries are less interesting—but in them we see that there was another Dos Passos, not the aesthetic tourist or sensitive young romanticist but the would-be professional novelist, collecting scenes of war and peace that might turn out to be useful somewhere, learning to write without the props of personal charm so evident in the letters:

Advertisement

Captain Pietra at Borso shot himself in the head today. He was a curious man—the sort of man who crosses the back of the stage in a Dostoevski novel now and then. He was the only embusqué in his family, he would tell you. “Today I shall go within thirty meters of the Austrians” he would say, sono il solo emboscato de mia famiglia. He must have been a coward for he had a sort of nervous mania for taking risks—a hectic anxiety to show you he was not afraid. He had a certain nerve though—he must have had to shoot himself so cleanly. I can imagine him looking down the barrel of the revolver and saying to himself “I am the only embusqué in my family—I’m not a coward.

But maybe he did it out of spite—He always used to get into frightful tempers.

All the Americans hated him.

(April 17, 1918)

It is at such moments, when the only immediate audience is himself, and literature, though not absent, is kept off to the side, that one sees Dos Passos learning to be a novelist.

Yet neither Ludington’s letters and journals nor Landsberg’s thorough reconstruction of his political involvements quite succeeds in showing Dos Passos coming into his powers as a novelist. Neither scholar seems to have had free use of all the existing materials. Ludington tersely remarks that “publication restrictions” prevented him from including Dos Passos’s letters to Arthur McComb, a pacifist Harvard friend with whom he corresponded about public events and issues for some twenty years, while Landsberg, who quotes from the McComb letters very extensively, apparently could not use much of what Ludington prints, though he did have the benefit of retrospective comments by the older Dos Passos and many of his friends.

Whatever pettiness of scholars or publishers may lie behind this division of resources, its results are unfortunate. Landsberg’s Dos Passos, a strong and passionate political man whose libertarian feelings drew him far to the left and then far to the right, is only partly visible in Ludington’s volume, which includes surprisingly few letters from 1925-1927, when Dos Passos was deeply concerned with the Sacco-Vanzetti case and other radical causes, the New Playwright’s Theater, and the beginnings of U.S.A.. Ludington himself labels the period from 1922 to 1927 “The Great Days,” yet this section is far shorter than those devoted to 1917-1918 and 1918-1921. No doubt Dos Passos was too busy, and perhaps too happy, to write as many letters as he had earlier, but it seems odd to find no reference to Sacco and Vanzetti until May, 1927, just three months before their execution, and no mention at all of his involvement in the Passaic textile workers’ strike in 1926, which Landsberg makes much of.

Landsberg’s chapter “Class Warfare,” on Dos Passos’s political activities between 1926 and his visit to Russia late in 1928, is obviously right in stressing the importance of these experiences to the author of U.S.A., but one would never know it from the infrequent and sketchy indications in the letters Ludington prints from this period. Indeed, it would be hard to know from those or later letters that Dos Passos was even working on a novel.

It’s a pity that Landsberg’s Dos Passos, a not particularly original thinker but a serious political man, and Ludington’s Dos Passos, a cosmopolitan man of letters with only part of his mind on social justice, couldn’t have been introduced to each other within a single pair of covers, perhaps with a reprinting of the “Camera Eye” continuity from U.S.A., which turns out to be almost unveiled impressionist autobiography. (Landsberg uses sections of “Camera Eye” effectively, but there’s more in it than suits his theme.) Combining the strands of this divided life could make it easier to see why Dos Passos’s art, especially in U.S.A., turned out as it did.

For example, after reading both books one begins to feel that Dos Passos’s political positions were no more a response to objective political and social conditions than they were expressions of his own inner plights or satisfactions. Only in the 1930s did Dos Passos begin to feel at home in America, rather too much so for the health of his writing, and this might as plausibly be related to the psychological security he achieved through his first marriage (1929) as to the suspicion of “foreign” ideologies he acquired in his painful encounters with Stalinism. To make such a suggestion is not of course to explain political experience as simply a reflection of a man’s psychology, but (as Landsberg cautiously suggests from time to time) Dos Passos’s private experience does seem to have made him peculiarly open to political feeling.

One begins to suspect that both art and politics were for Dos Passos, whether he knew it or not, adjuncts to private life and feeling rather than vocations, in the strongest sense of that word. Certainly in the 1930s, as he began his dramatic withdrawal from his radical attachments, he remained on affectionate terms with friends like Edmund Wilson and John Howard Lawson, whose views didn’t keep pace with his own, and his quarrels, with Malcolm Cowley and Hemingway, for example, hinged more on supposed breaches of personal trust than on nominal political disagreements. “But dammit,” he wrote to Wilson of Cowley’s behavior in printing a private letter in the New Republic, “if people dont act straight in small things how are they going to act when a really important issue comes up [?]”

Politics was something that gentlemen might disagree about without ceasing to respect and like one another. Dos Passos seems to have known all along that no ideology could by itself satisfy his libertarian instincts, that positions and causes were to be taken up and put aside according to how well they advanced his own sense of progress toward social and individual justice. “Whether the Stalinist performances are intellectually justifiable or not,” he wrote to Wilson in 1935, “they are alienating the working class movement of the world.” The idealist, the man of principle uncommitted to particular ideologies, could be more practical and historically minded than the communists themselves, and it was a role he seems to have relished.

Certainly in U.S.A. Dos Passos is moved not so much by political causes as by the need of confused and victimized people to believe in them. It seems to me that the predicaments of his characters mainly concern him as they project displaced and simplified images of his own predicament, his sense that politics both served and ultimately disappointed his need to feel connected with other people. This was the need, I suspect, that not only produced his best novels but made it unnecessary for him to keep working at serious fiction after his personal and political sense of himself became firmer in the early 1930s.

Certainly the younger Dos Passos was virtually an encyclopedia of alienations. Born a bastard, he took the name Dos Passos only when he was fifteen, upon the marriage of his adored mother to the man whose mistress she had been for more than twenty years. That father was a physically vigorous self-made man with a splendid mustache, the son of an immigrant from the Madeira Islands, whose rise to prominence and wealth as a New York corporation lawyer turned him into an apostle of Anglo-Saxon supremacy—he advocated denying citizenship to the foreign born, among other things. Dos Passos came to admire his father, who was neither a fool nor a plain reactionary—in 1934 he prophetically remarked in a letter to Edmund Wilson that “it would be funny if I ended up an Anglo-Saxon chauvinist—Did you ever read my father’s Anglo Saxon Century? We are now getting to the age when papa’s shoes yawn wide.” But such a father has wide shoes indeed, especially for an only son like Dos Passos himself, with his weak eyes, incapacity for sports, foreign looks, and an accent and outlook formed by a childhood spent largely in Europe.

The sense of manhood, like other senses of being in the right place, came hard to Dos Passos, as scenes in “Camera Eye” make pretty clear:

you sat on the bed unlacing your shoes Hey Frenchie yelled Tylor in the door you’ve got to fight the Kid doan wanna fight him gotto fight him hasn’t he got to fight him fellers? Freddie pushed his face through the crack in the door and made a long nose Gotta fight him umpyaya and all the fellows on the top floor were there if you ‘re not a girlboy and I had on my pyjamas and they pushed in the Kid and the Kid hit Frenchie and Frenchie hit the Kid and your mouth tasted bloody and everybody yelled Go it Kid except Gummer and he yelled Bust his jaw Jack and Frenchie had the Kid down on the bed and everybody pulled him off and they all had Frenchie against the door and he was slamming right an’ left and he couldn’t see who was hitting him and everybody started to yell the Kid licked him and Tyler and Freddy held his arms and told the Kid to come and hit him but the Kid wouldn’t and the Kid was crying

Of course, worse things happened to boys like Dos Passos at schools like Choate, and he grew up into an outwardly easier relation with his environment. But his academic and social success at Harvard cost him something:

…four years under the ethercone breathe deep gently now that’s the way be a good boy one two three four five six get A’s in some courses but don’t be a grind be interested in literature but remain a gentleman don’t be seen with Jews or socialists

* * *

but tossed with eyes smarting all the spring night reading The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus and went mad listening to the street-carwheels screech grinding in a rattle of loose trucks round Harvard Square and the trains crying across the saltmarshes and the rumbling siren of a steamboat leaving dock and the blue peter flying and millworkers marching with a red brass band through the streets of Lawrence Massachusetts

It took him a long time to achieve anything even remotely like his father’s confident ease among confident people. Whatever else it is or isn’t, U.S.A. is an epic of modern American loneliness, of people in transit from somewhere that hasn’t worked out to somewhere else, where things may be better.

Dos Passos himself was a compulsive traveler all his life, and of course he had the advantage over his characters of being able to take positive pleasure in the destinations, geographical and intellectual, that his cultivation had prepared him for, particularly the European ones. But he tried to see both his life and theirs—from Mac the Wobbly at the beginning of U.S.A. to “Vag” at the end, the young Depression hobo trying to hitch a ride “a hundred miles down the road” from whatever it is he wants and can’t have—as victimized by an unjust social and economic order.

The effort was an important and honorable one, and if the perspective was only partly true, at least in his own case, it becomes all the more essential to get straight the connections between his public and private selves that give his politics more than an obvious “representative” significance. Whether such an understanding would make his novels seem better as literature is another question, though I suspect that it might; but in any case Dos Passos needs to be put together again, and for all the value of the two studies at hand, one hopes for a full biography, using all the materials, that can do the job.

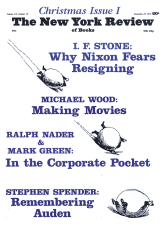

This Issue

November 29, 1973