The first volume of Pierre Goubert’s Ancien Régime, which was concerned with French society between roughly 1600 and 1750, was published in 1969 and reviewed in these columns in January, 1970. The second volume, which has just come out, covers, for the greater part, the same period as the first, and deals principally with the state and its relations with the main social groups.

These works are a landmark in French historical writing for two reasons. In the first place Pierre Goubert, a professor at the University of Paris who won for himself an international reputation in 1960 by his study of Beauvais and the Beauvaisis between 1600 and 1730, is the first Frenchman of repute in the last fifty years to have attempted a specific study of the ancien régime as distinct from devoting a chapter or so to it by way of introduction to a history of the Revolution. Indeed apart from one or two writers whose works are no longer read, he is the first Frenchman to undertake this task since Tocqueville published his Ancien Régime et la Révolution in 1856.

In the second place, though Professor Goubert is a member of the French academic establishment, he attacks the judgments on the ancien régime to which this establishment has subscribed in the last half century and has repeated ad nauseam in textbook after textbook, notwithstanding the mounting evidence against them.

It has long seemed that French historians were deaf to all arguments where the ancien régime was concerned. However incontrovertibly the facts spoke against them, nothing, it appeared, would stop them from reiterating that the Revolution was a bourgeois revolution, and from doing so not on the indisputable grounds that it made possible the emergence of bourgeois society, but on the untenable grounds that it was the culmination of a class struggle between an unprivileged bourgeoisie, which throughout the eighteenth century had been continually growing in wealth and self-consciousness, and a privileged nobility, which was becoming progressively more exclusive and impoverished.

These assertions were not only based on self-contradictory arguments; they were refuted seriatim by facts which the French themselves increasingly revealed in doctoral theses and other monographs. It was, however, American and British historians who first publicly expressed a sense of outrage at their continued repetition. For long these protests were ignored. As Professor Cobb once put it: what right had mere foreigners to challenge the judgments of such eminent native scholars as Georges Lefebvre and Albert Soboul?

Now, however, Professor Goubert, with all the prestige of an established reputation and a chair in Paris to back him up, has come out on the side of the foreign historians. His work is a deliberate protest against current historical beliefs and attitudes. He prefaces his second volume with a plea to bring to the study of the ancien régime the intuition and sympathy without which it cannot be understood, and to look at the facts with a fresh and unprejudiced mind. When he himself observes these principles he can achieve excellent results, as for example in his treatment of the peasant question, of the provincial estates, of the Crown’s desire for centralization on the one hand but reluctance to enforce it on the other. His work is both a mine of factual information—there are chapters which read like Marion’s Dictionnaire des Institutions de France—and a source of new interpretations and insights which dispose of many long-accepted opinions.

In his first volume he asserted, citing evidence to prove it, that the French Revolution cannot be explained as “the triumph of an unidentifiable capitalist bourgeoisie over an unidentifiable feudal aristocracy.” In his second volume he proceeds (and sometimes further than many who would agree with him about the above quotation may find warranted) with his work of demolishing the current orthodoxy.

He doubts whether one can accuse the nobility of sponsoring a reactionary policy in the last days of the regime, as all the works touching on this period maintain; the greater part of the bourgeoisie, he says, was integrated into the regime and thus not revolutionary. In an eloquent passage he disposes of the myth of an exclusive ruling class of hereditary aristocrats. High society, he shows, was a society in which wealth, power, and prestige were united; which was composed of people of many different origins—of men of talent, of financiers, of the luminaries of the civil and military establishments. It was a society in which members of the oldest noble families rubbed shoulders with members of the most recent; which drew its wealth from many different sources; which avidly pursued money, pleasure, and new ideas; which served the regime and yet continually criticized it; in which schools of thought and coteries grew up, dissolved, were formed anew, and, more or less unconsciously, worked toward the only “revolution” (the quotation marks are Professor Goubert’s) for which the best practical brains hoped—a liberal constitutional monarchy.

Advertisement

What Professor Goubert says in this passage and in many others has the ring of truth, but will he succeed in changing the accepted view of the ancien régime? If such a change were to occur it would no doubt do so principally because of changes in the political opinions of the French academic world. The interpretation he attacks, though unusual in the West because of its flagrant indifference to the facts, was, like all historical interpretations, a matter more of ideology than of scholarship—of an ideology which interpreted the French Revolution in the light of the Russian and saw it as a stage on the road to communism. As Professor Goubert himself observes: what French historians have written on this subject tells us more about themselves than about the situation they purported to describe.

It has happened in the past that when ideologies, and the historical interpretations they have inspired, have come to seem inadequate, a writer of talent has crystallized the inchoate dissatisfactions with them into some new explanation which has then exercised a great influence on public opinion. This is what Albert Mathiez (the founder of the school of thought which Professor Goubert is attacking) did in the 1920s when he published his work on the French Revolution.

One cannot, however, see Professor Goubert filling a similar role because he lacks a sufficiently clear vision. Though he analyzes many problems admirably his work is not a coherent whole. Indeed to judge by the medium of expression he has chosen and the terms of reference he has imposed on himself, he cannot seriously have intended that it should be.

His medium is the textbook “written to be useful,” presumably to university students. Though the order of facts he selects for discussion is to a large extent different from that commonly found in textbooks, the way he presents his material would be possible in no other kind of work. To start with there is the didactic manner. Though this is less obvious in the second than in the first volume, the voice of the professor instructing his class is still audible. Each chapter is divided into a number of sections; the words and phrases of which the student should take particular note are put in italics; there are no footnotes but, with one or two surprising exceptions, each chapter is followed by a short list of important works for further reading and by extracts from contemporary documents.

Such didacticism in a learned work is a substitute for thinking things out clearly enough to permit an argument that is self-explanatory. Professor Goubert, it would seem, has not allowed himself the time to produce this. He is an expert on some of the subjects with which his title requires him to deal but not on others. He has attempted to find a way out of this difficulty by assuming that the ancien régime began in 1600 and ended in the middle of the eighteenth century (the dates he chose for his doctoral thesis) and by deciding to concern himself only with those features of government and society that remained constant throughout this period. It was clear in his first volume and is even clearer in his second that these time-saving devices do not work satisfactorily.

The term ancien régime, like other descriptions of a particular way of life and government, is only a more or less convenient label. As Professor Goubert himself points out: it has meant many different things at different times and to different people. There is nevertheless one thing it has always meant since it first gained general currency in 1790. It has meant the regime which the Revolution destroyed. Tocqueville spoke of “l’ancien régime et la révolution” and this conjunction seems inescapable. Professor Goubert’s attempt to write about l’ancien régime sans la Révolution breaks down for the reason that all arguments break down that attempt to give a term a meaning different from that commonly ascribed to it. He cannot abide by his own terminology.

However much he may insist that he is not primarily concerned with anything that happened after 1750, the Revolution is continually present to his mind. In Volume I he begins with it. In Volume II he constantly refers to it. Indeed at the end of this volume he so far departs from his original intentions as to devote his last chapter to the features of the ancien régime which it left standing, and the three previous chapters to social and economic changes which preceded it.

These last four chapters account for one-third of his second volume. They are full of interesting pieces of information but they lead to no conclusions. Professor Goubert does not consider how far the changes between roughly 1750 and 1789 which he enumerates contributed to a revolutionary situation, and there are many changes he omits to mention. His references to the causes of the Revolution (not to mention the references to its consequences) are incomplete and arbitrary, since this is a question to which his scheme affords no place, though he is unable to leave it out of account.

Advertisement

His determination to deal only with the permanent aspects of government and society between 1600 and 1750 creates even greater difficulties for him, particularly in his second volume; for many things, as he himself admits, did in fact change during these one and a half centuries, and even in his earlier chapters he cannot avoid taking some of them into account. He does not, however, seem to have been guided by any principle in his choice of the changes he will mention and those he will omit. Sometimes, as for example in his account of the army, and of government expenditure, he carries his analyses up to 1789, but at other times he stops much earlier, on a number of occasions as early as 1715—for example in his description of the methods used by Louis XIV, but largely abandoned by his successors, to cheat the purchasers of office of their money. Often only the initiated will be in a position to know at what point he has chosen to stop (for dates are frequently lacking) and which of the situations he describes changed or remained the same during the last forty years before the Revolution.

Professor Goubert, in fact, proceeds after a fashion familiar to all people who have had to write lectures in a hurry and from material that does not entirely fit the title of the course. He sets out what he knows. He dilates on the points that interest him. He airs his prejudices (drawing parallels, for example, between the French administration in the eighteenth century and today to the latter’s detriment).

Sometimes he is excessively scrupulous about not going beyond the evidence—he will say nothing at all about the French navy, not because nothing is known about it, but because the subject is one on which scholars are now at work and have not yet reached conclusions. At other times, however, he takes familiar judgments at their face value, as when he suggests that no government in his period could survive if it spent approximately 50 percent of its revenue on servicing the debt. This, however, as Necker knew, was precisely what the British government did on more than one occasion in the eighteenth century. Often he makes difficulties just, it would seem, for the fun of it, as when he heads one section: “The (probable) root of the problem” of finance. Why “probable”? Professor Bosher, from whom the information in this section comes, appears to have been in no doubt about the answer.

In spite of the respect Professor Goubert professes, and often shows, for the facts, there are occasions when he makes sweeping assertions without attempt at proof or explanation. On page 210, for example, he maintains that “objectively speaking” there were practically no provincial nobles who were poor. Jean Meyer, he says, has “settled the question.” Jean Meyer, however (on page 35 of the shortened edition of his La Noblesse Bretonne au XVIIIième Siècle), points out that in Brittany there was “a veritable noble proletariat” and refers to one district where a third of the nobility was “reduced to beggary.”

It is to be feared that the irresponsible assertions of which Professor Goubert is guilty from time to time will deprive his valid theses of the respect they deserve. It will also not be difficult for the school of thought he attacks to point out that notwithstanding his services to scholarship his judgments are often naïve. In one passage, for example, he attributes the outcry against the taxes in his period, and the difficulty in collecting them, to an inherent aversion to paying taxes peculiar to the French nation. He does not seem to have considered that the French system of taxation, proverbially among contemporaries in the eighteenth century the most arbitrary in Europe, was calculated to produce this effect in any community. He continually suggests that the Revolution need not have happened, but gives no reasons for this opinion except by pointing out that Louis XV and Louis XVI lacked the energy and decisiveness of Louis XIV. This is an explanation long favored by the unsophisticated. It overlooks the fact that incompetent and indecisive kings were a natural consequence of absolute monarchy, which at a certain stage of social and political development commonly led to disaster.

Because in his epilogue he lists only those features of the ancien régime which the Revolution left standing, and says nothing about the ones it destroyed, it may even be brought against him that besides believing (or half believing, for he is not consistent on this point) that the Revolution could have been avoided, he also believes that it achieved nothing.

The mixture in Professor Goubert’s work of sophistication and naïveté, of scrupulous scholarship and carelessness, of excellent pieces of analysis on the one hand, and non sequiturs, misstatements, and arbitrary omissions on the other, may seem surprising in so eminent a scholar. Given the present climate of opinion, however, particularly in France, this is not so surprising a mixture as the uninitiated might suppose. Historians at the moment, and again particularly in France, are attracted to sociological investigations pursued in a narrow field—a predilection which is encouraged by the nature of the French doctoral thesis.

The large themes are falling out of fashion, partly no doubt because they demand a different kind of technique from that now required to make an academic reputation, and partly because they are not susceptible of explanations that can be proved, whereas in a narrow field of sociological inquiry it is possible to reach a comforting certainty. General works, in consequence, which can be read with pleasure and instruction both by the student and the educated layman, are being replaced by textbooks for students only. Textbooks, however, by definition, are a form of literature of no very high order which reputable scholars may be induced to write for various reasons, but which they can rarely bring themselves to take with the seriousness necessary to produce a coherent, illuminating explanation.

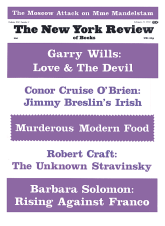

This Issue

February 21, 1974