It begins when a match is struck on a darkened hotel porch, and a soft voice rasps “th’ equivocations of the fiend.”

“Where the devil did you get her?”

“I beg your pardon?”

“I said: the weather is getting better.”

“Seems so.”

“Who’s the lassie?”

“My daughter.”

“You lie—she’s not.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“I said: July was hot. Where’s her mother?”

“Dead.”

Humbert Humbert knew, without knowing it, that McFate would speak in time—“Aubrey McFate,” the obscure thwarter hovering somewhere. Even when this private devil acquires a face (and endless cars), there is nothing to call him, for a long time, but McFate. Only when clues jumble near each other for a long time do they, clair-obscurely, finally spell out in patches this devil’s name: Clare Quilty.

Nabokov’s Lolita is (at last estimate) two thousand or so things—prominent among the rest, a detective story. (McFate is sometimes called Lieutenant Trapp.) As in Crime and Punishment, the detective is also the criminal; but Dostoyevsky makes Raskolnikov play this double role, back and forth, through a policeman essentially outside the crime: he must stalk the man who stalks him. Humbert and Quilty, by contrast, track in on each other as mutual accuser-criminals, growing toward each other’s destruction, Humbert in terror and Quilty with a leer. Not only Humbert, but Lolita herself, is possessed by Quilty, who can only be exorcised at last by murder. This detective story does not solve a crime, but is solved by one.

It is also, of course, a love story, as many have realized. All the clinical talk of girls half-nymphed into womanhood—time’s mermaids, amphibious, belonging fully to neither world—is in the long run misleading. Lolita does not fulfill Humbert’s obsession with nymphets she destroys it. His concern had been for a type, cocooned outside of time in a frozen moment of becoming. The mounted butterfly cannot decay, because it cannot (any longer) live. Humbert, with a thousand such butterfly slides to view, in his poise of remote satisfaction, meets Lolita at just her moment of chrysalus—loss and descent from nymphethood—and he follows her down. The two years of his life with her, and the two years after, are all post-nymphet years. He sees her last in a splayed and cowlike pregnancy, and never loved her more. By his own fastidious measure, cultivated half a lifeless lifetime, she represents his fall from an aesthetic state of grace. He dies into time with every sag of her flesh. Having flirted with her in his Eden of the mind, he loves her outside the fiery gates—now his and her flesh darken together back toward earth. He is redeemed by his fall, made capable of loving. And so capable of damning her.

She was only the faint violet whiff and dead leaf echo of the nymphet I had rolled myself upon with such cries in the past; an echo on the brink of a russet ravine, with a far wood under a white sky, and brown leaves choking the brook, and one last cricket in the crisp weeds…but thank God it was not that echo alone that I worshiped. What I used to pamper among the tangled vines of my heart, mon grand pêché radieux, had dwindled to its essence: sterile and selfish vice, all that I canceled and cursed.

Lolita is an even rarer thing than an honest love story. It is our best modern hate story. Unrequited love is, from the outset, half made up of hate. Self-hate for loving—or else, on the other side, for not loving; a shared intimacy of detesting, uncontrollable as love itself. To be the unwilling object of another’s love is embarrassing, oddly debilitating. What should be a reciprocal relationship is both interrupted and uninterruptible; an intensely “personing” energy pounds at the unresponding object, thrusting an Other in on a violated Self. It gives the loved an unwanted responsibility for the lover, victimizing the loved as an unwilling victor.

It is common to say that we become, in some measure, those we love. It is a circularly weird fact that we become, will we or not, those who love us. The very lack of reciprocation forges a bond. After all, no one cares as much for anyone as does that person’s lover—except each of us caring for himself. No matter what the division or barriers between a cold loved person and the lover, they agree on one crucial point—both do love the same person. There is a union achieved by reason of a common object, which is the one kind of union lacking in the true reciprocity of love, where the lovers have different objects—A’s being B, and B’s being A. In the case of the loved unlover (who is an unmoved mover), the secret tie lies in a barren uniformity under all the reversals: both A and B love A, and only A. Set apart in all things else, on this point they are undivided—and what was put apart in heaven cannot be sundered on earth. The broken circuit pours all its electrocuting force into the point of rupture, which is a unifying focus. Bound, by division.

Advertisement

This is the bond Humbert and Lolita share, wedded by her unresponsiveness. She accepts that burden, and even appeals to it, later, asking for financial support as a dark marriage right. But as they both loved the same object (“Lo”), they are also linked, in a camaraderie of plague victims, by hating the same object: the Humbert mirrored back on Humbert in her own revulsion or coarsening. Eve cannot hate the serpent near as well as the serpent does. The love that freed Humbert from Eden—and now binds him—crippled and distorted her. There is nothing crueler than love. He needs her, and diminishes her by the need; and despises himself for doing so. He preys on what he admires, destroying it with admiration. He is her tempter, but also—quite sincerely, as he assures Quilty at the end—her father. Both God and Satan to her, creating and undoing her. Romantic agony over his own deterioration he could stand, and even prettify. But love breaks him out from all such excuses into a larger prison—hers, the one he forged for her in darkness. His hell is the fact that he damned her. Listening from a hill to the play of children, he muses:

One could hear now and then, as if released, an almost articulate spurt of vivid laughter, or the crack of a bat, or the clatter of a toy wagon, but it was all really too far for the eye to distinguish any movement in the lightly etched streets. I stood listening to that musical vibration from my lofty slope, to those flashes of separate cries with a kind of demure murmur for background, and then I knew that the hopelessly poignant thing was not Lolita’s absence from my side, but the absence of her voice from that concord.

Love destroys. We all seduce and abuse one child, the one we once loved best, the one we were born as; and we mistreat all others in obscure revenge for what was done to us (mainly by us). Of course, Lolita’s fall—like Margaret’s—was “the blight she was born for.” It is, always, Margaret we mourn for. But woe to him by whom the scandal comes into the world. Humbert, fallen, can pay that price—this constitutes his superiority to the prelapsarian dandy of the book’s first pages. But he “rose” to moral responsibility by making her fall with him.

Why is Quilty needed? Humbert is quite sufficient to his own dis-Edening. We all glide as our own serpent into our own garden. Why blame this on any other? Humbert mirrors the answer back on Humbert: the hate in him mocking his love, growing with it, inseparable—until he kills it, hating his hatred out of existence, destroying himself for love. The intertwinedness of love and hate at their height does not correspond, as we dimly experience that clash, to neat metaphysical defenses of “all being as good.” By this account of things, evil is nonbeing (a defectus entis)—not something positive itself, but the failure of all being that is limited, the brink, the fall-off into nonbeing, the point where good ceases to be good because it ceases to be anything at all.

Whether that argument makes sense to philosophers, I do not know. But it hardly matters to the rest of us, persons involved in stories—it is the very essence of our grasp upon ourselves that we figure in various plots. And in stories, for many and deepest reasons, evil is always a villain. Evil comes at us personified because we grasp it in ourselves as a person’s act. We are at our worst, not where we tend not to be at all, but at the very peak of our powers. We get into “towering” rages, and are “beside ourselves” with an overflow of destructive indignation. We become something more just as we are making others less—Humberts feeding on our own Lolitas, our loved things marred. Evil is what Milton called it, “Heav’n ruining from Heav’n,” the highest things in us deliberately reaching down.

There is a Humbertian irony in the fact that William Blatty, author of The Exorcist, chose Teilhard de Chardin as his model for the book’s saint, for the practiced wrestler with embodied fiends. Teilhard, that anthropological mystic, believed in the defectus entis approach to evil. For him, evil was the mere lag that any temporal evolution must entail—and since evolution moves away from inert matter and on toward universal personhood, he must deny the existence of a Lucifer whose fall predates man’s rise. (What was there, before the omegaing of man and time, to “fall,” or to fall from?) Evil is, for him, the blind backward tug and brute reluctance of that marble from which evolution is sculpting the person. It is literally “low life,” falling away from the evolutionary mainstream toward no-life.

Advertisement

But everyone knows the devil is a toff. He is not low on the scale of being, but intimidatingly high—in art as well as doctrine; and, most important of all, in us. There is something in man that promotes treason at the top of his best efforts, that turns back and betrays—and grows by betraying, displaying new human powers. It is no good to talk, in this area, of man’s mere encasement in the flesh, or the world’s solicitings. Lucifer rebels in the clouds, and falls from them, in regions where mere hatred becomes selfless, rapt by an ideal of undoing.

And the barest branch is beautiful

One moment, when it breaks.

God, as Chesterton wrote, made the world and saw that it was good—mud and sky and flesh. But hell is all a work of the spirit. It is terrifyingly high, not low, on the evolutionary scale.

Real hatred, the staggering mysterious thing, has a kind of purity to it. Men surpass themselves, reach out, open windows of transcendence, by hatred as easily as love. All men are the same to Moby Dick. Only Ahab seeks the one thing consecrated by his hatred. Nature, red in tooth and claw, ravages mildly, with impartial voraciousness. Man alone reaches that height from which the real fall comes—the odd selflessness of hatred, trying to reverse creation. And as unrequited love intrudes without mercy on a man, so does apparently motiveless outside hate. The nut mail arrives, signaling one’s importance to a stranger, the heat of a total person radiated toward one in reverse devotion. It is like being cared for by a very solicitous nurse from hell. Love tries to absorb the other, and so does hate. The unwilling recipient of this attention has obviously inflicted an agony he was unaware of, just like the loved person who cannot respond.

In this way does the cool, intelligent malice of Quilty dog and disanimate Humbert till he turns at bay to hunt down his hunter. Everything doubled and palindromic in Humbert Humbert—the father who cradles, and rapist who tore—adds up to the need for exorcizing Quilty. In the hall of mirrors that is man, we always mean more (or less) than we mean to mean; and are more or less than we aimed to be, minute by minute. And each of our other selves—greater or lesser—born out of the shadowy “real” self, nags at and haunts us. That must explain Plato’s strong appeal to artists—the creative idea of oneself, pitted against the idea’s mere reflection, so much less than we fantasied. Yet where did the “greater” fantasy come from but this “lesser” actuality? An “ought” echoes mockingly our “is,” yet is the is, or comes from it. The prelapsarian I judges the fallen I—by permission of the fallen I’s mind and struggle to be truly “I” and a soul. We fell before we were.

Yet that “I” which is before the world began can tower into dark majesty as well as primordial light. Quilty has not descended into the flesh by loving Lolita. He represents the pure butterfly-collecting Humbert of the book’s first pages, living on untouched, playing in lepidopteral heaven—until boredom begins to twist the colored slides new perverse ways. Quilty uses and moves on, laughing. Of course, his amusements become more recondite, as his final temptations to Humbert indicate: he would have his chum with a gun join him in connoisseurship of “a young lady with three breasts, one a dandy.” He barely remembers the girl who gave Humbert a soul to be damned. He remains a Humbert not yet fallen down toward love, a truly angelic mocker.

And Lolita is still fascinated by that “higher” Humbert, to which the lower one introduced her, seducing her—as it turns out—for another. His other. So Quilty must be destroyed, to rescue her. In the novel’s mythic scheme, we never question the necessity of killing Quilty. Devils must be exorcised, destroyed even when this is self-destruction. Humbert therefore kills, like Ahab, trammeled up in his own act: “I rolled over him. We rolled over me. They rolled over him. We rolled over us.”

This fierce exorcism over, Humbert rests in his own hell. Destroying his image, he has stepped through the mirror, gone where his simius Dei dwelt, whence he looks out now, suspended in an eternity of upside-down, the last Orwellian state:

The road stretched across open country, and it occurred to me—not by way of protest, not as a symbol, or anything like that, but merely as a novel experience—that since I had disregarded all laws of humanity, I might as well disregard the rules of traffic. So I crossed to the left side of the highway and checked the feeling, and the feeling was good. It was a pleasant diaphragmal melting, with elements of diffused tactility, all this enhanced by the thought that nothing could be nearer to the elimination of basic physical laws than deliberately driving on the wrong side of the road. In a way, it was a very spiritual itch. Gently, dreamily, not exceeding twenty miles an hour, I drove on that queer mirror side.

The “wrong side” is now his natural condition. He has achieved his hell through love, and the entire book, written in retrospect, is a set of love letters from hell. Hell, that is, is not an absence of love (defectus amoris), but a conscious love that tortures itself for what it has done to the beloved:

Unless it can be proven to me—to me as I am now, today, with my heart and my beard, and my putrefaction—that in the infinite run it does not matter a jot that a North American girl-child named Dolores Haze had been deprived of her childhood by a maniac, unless that can be proven (and if it can, then life is a joke), I see nothing for the treatment of my misery, but the melancholy and very local palliative of articulate art.

So the hellish letters get written. By killing his devil-image in the mirror, Humbert has achieved his self-abdication, and can rest in hell.

Admittedly, Quilty is a fantasy within a fiction, Humbert Humbert’s endless humbertizing, the shadow of a shadow. Mere symbol. But to call the devil a symbol is not to answer much. A symbol of what? Is it a necessary symbol? Does it say something for which we have no better sign or language? Why do men resort to this symbol again and again, in fresh circumstances? Literature is haunted by the evil Doppelgänger—the huge dim image reflected back on man as he both stretches himself out and diminishes himself in the endless tug and self-rendings of trapped hate and love. Why, that is, does man so often come, at his best moments of discernment, to understand himself as an angel looking at the devil in a mirror?

Lolita would not be the masterpiece it is without Quilty. The devil is, at least, necessary in that sense. Humbert, however complexified internally, needs his “outside” devil to become himself—by destroying himself. There is no question, here, of shifting blame onto another. We come to be, after all, in and through others. The serpent is in Eden for the same reason that Adam and Eve are—they must have a dialogue to have a seduction; man falls as part of a story, and drops into history.

And if calling the devil a mere symbol does not truly lay that ghost whose strength has always been precisely as a symbol, what are we to make of the dismissal of our devils as mere “personifications”? What else can persons do but “personify” themselves and others, in the dialogue that gives them a story—i.e., a self? The mind—incapable of parthenogenesis, of being by simply thinking, of impregnating itself with an idea—does achieve mutual autogenesis with other minds, which mate themselves into existence, becoming their own and each other’s offspring. Each mind is, at its least, two “generations”—parenting and childed, simultaneously, in and on others. What will the offspring be? That depends on the entanglements of love and hate. Lolita, blossoming and blighted through Humbert, will reciprocally blight him in his blessed fall.

All our children are, in some measure, Rosemary’s babies—and are ourselves. We play Laius to our own Oedipus. The mind “personifies” itself in others. “Selves.” Throws off lesser or larger images of what it is—an image. Who is not a “personification”? We day by day create and uncreate each other in each other, suffering the gain-loss of our love-hates in endless chain reactions. We angel or ape on each other in half-conscious passing fits of mental coition, dealing and receiving life or death in a word or smile, filling the air with angels or devils that are our mental progeny; then driving off the devils, or beckoning them back. We all live by a mutual rescue, and die by a suicide pact. That is our shared original—and terminal—sin. History is a dialogue, of man with man, man with himself, each man with his own serpent. And as heart speaks to heart, our serpents, too, are whispering together.

Hell is others? Yes. And so is heaven. Just as hell is self, and so is heaven. We damn and redeem each other in a dialectic, by inextricable bindings and loosings. Others touch us, and strength flows from us, to help or hurt; cripple, or cure cripples, as we pass; exorcise, or possess. We blunder on, angeling in ape-form, falling from our angelhood just at the instant when we, at last, perceive it, living our death as we undo our lives. There is a doubleness to all we do, the balancing fall into love and rise into hate, the hovering and cloudy battle done over our heads by our best and worst at their alien height within us.

Is this devil enough, powers and principalities enough to prey in and on us; and, through us, in and on others? Perhaps—perhaps that is why we want to disentangle ourselves from such disturbing thoughts, and those works of art which lift us up where great men battle darkness. Better, it seems, to breathe free under a spiritless sky and in a dry vista. But at times that rasp and whisper can still be heard, behind us. Is it a person, an image, a symbol? Oneself, or a part of oneself—or that self “personed” in others? Part of me? Then which part? That which went out and reached others, mingled with them, grew large and came back at me as alien, unwanted? The corruption I bred absent-mindedly in others—the child come home for revenge on its parent? A person, a necessary aspect of personality; an inter-person, a “personing” where our spirit touches others?

One of these, or all of them? Whatever. It is Quilty. Deliver us from Him.

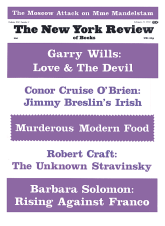

This Issue

February 21, 1974