Largeness, magnitude, quantity: it is commonplace to speak of Brazil as a “giant,” a phenomenon spectacular, propitiously born, outrageously favored, and yet marked by the sluggishness of the greatly outsized. And so the giant is not quite on his toes, but always thought of as rising from the thicket of sleep, the jungle of rest, coming forth from the slumbering dawn of undisturbed nature. This signaling, promissory vastness is the curse of the Brazilian imagination. Prophecies are like the fall of great trees in a distant forest. They tell of a fabulous presence still invisible, scarcely audible, and yet surely moving amid the waving silence of real possibility.

Brazil—remember the opening of Tess of the D’Urbervilles? The D’Urberville father with his rickety legs, his empty egg basket, his patched hat brim, is addressed on the road as “Sir John” because the parson has discovered that he is a lineal representative of the ancient, noble family of the D’Urbervilles. Brazil is a lineal representative of Paradise, the great, beckoning garden of delicious surfeit—a sweet place, always to be blessed. In Brazil the person stands surrounded by a mysterious ineffable plenitude. He lives in a grand immensity and he partakes of it as one partakes of thereness, of a magical placement in the scheme of nature. Small he may be, but the immensity is true. His own emptiness is close to the bone and yet the earth is filled with the precious and semi-precious in prodigious quantity, with unknown glitters and granites, with sleeping minerals—silvery- white, ductile. These confer from their deep and gorgeous burial a special destiny. This is the land of dreams.

Think of the words and their resonance—grande, grosso, Amazonia. Numbers enhance, glorify, impress: larger than the continental United States, excluding Alaska, and slightly larger than the great bulk of Europe lying east of France. Its borders flow and curve and scallop to the Guineas, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia, Argentina, Peru, Colombia, Venezuela. Out of this expanding, encroaching, bordering, nudging sovereignty, life reaches for a peculiar consolation and hope. Where there is isolation, loneliness, and back- wardness, where the tangle of life chokes with the complexity of blood and region, where torpor, negligence, and a strange historical lassitude simply and finally confuse—there even the worst is thought of as an unredeemed promise, not an implacable lack. Delay, not unalterable natural deprivation, is the worm in the heart of the rose.

Growth is mystical. The ignominious military rulers carry it as a banner. They kill, torture, repress in the name of the great, floating, swelling, primordial dream. The jungle, the historic, romantic coffee and sugar plantations, the crazy rubber Babylon of Manaus falling into ruin way up the Amazon, the marble shards of its opera house: all of that, the military seems to say, is folly, a siesta slump of some nodding mestizo, the old tropical slack.

A beggar, bereft, a leprous bundle of ancient Brazilian backwardness, a tatter of the rags, an eruption of the sores of underdevelopment: there he sits against an “old” 1920 wall of Sao Paulo. Without a doubt, he, shrunken as he is, salutes the punctured skyline, salutes the new buildings that from the air have the strange look of some vibrating necropolis of megalomaniac tombs and memorial shafts—all, like our own, enshrouded in a thick, inhuman vapor. Around the somnolent beggar the cars whir in a thick, migrating stream. And there it is, magic visible, vastness palpable, quantity realized, things delivered.

Yes, all will be filled, all will be new, tall, thrusting, collective, dominating, rapid, exhausting, outsized like the large, stalky watercress, the big, round tasteless tomatoes grown by the inward, enduring will of the Japanese farmers. It is an emanation, sacred; and yet, of course, a mean, mocking paradox, for this “growth” now seems an anachronistic mode—embracing late what has elsewhere been created early and has turned into a puzzle and challenge and menace. Poor Brazil: the beginning and the end meet in a tragic collusion and collision. Still it must be as it is. There is indeed no other way. No one will consent to turn back.

In Brazil the presence of a great, green density makes the soul long to create a gray, smooth highway. Thus Corbusier in 1929 saw Rio, radiant, and said, “I have a strong desire, a bit mad perhaps, to attempt here a human adventure—the desire to set up a duality, to create ‘the affirmation of man’ against or with ‘the presence of nature.’ ” The affirmation was to be a huge motor freeway. Underdevelopment, rest, nature turn the inspiration to engineering. Glory in Brazil is glory elsewhere, a vast junk heap of Volks-wagens, their horns stuck for eternity. The new world rises from the hole in the ground where once stood a mustard-colored, decorated stucco with its little garden. Buildings, offices, hotels: in the swimming pools beautiful butterflies float in their blue-tiled graves. The mellifluousness of the tropics—birds, hammers, the high hum of traffic.

Advertisement

The endless, aching shore lines. Life under the Great Southern Cross. Cruzero du Sul: under the blazing sky or the hanging humidity a resurrection of steel, stones; the transfiguration of metals, of dollars and yen. And death to students, to culture, to the young, the teacher, the writer, the priest, the radical, the democrat, the guerrilla, the humorous, the theatrical, the mocking, the generous, the reporter, the political past. The pastoral, romantic world of Gilberto Freyre, with the masters and slaves in a humid comingling, the old stately prints of the family and servants trailing, single file, in dramatic dresses and hairbands, to the plantation chapel. The land and its murky history are buried under the devastation of death squads with their motorized units, their electric prods, their “methods,” their Nordic interrogations, DOPS (Department of Public Order and Safety), decompression. Words fill a vacancy, the hole in the heart of the Brazilian government. No desire to heal, to warm, only to rule without pity.

I had been here for some months in 1962 and now in 1974 I returned—to see what? It was a time of celebration for the military regime. They had ruled for ten years and yes his time had come. Geisel, the new president, stands in the pictures; he is colorless, as ice is colorless, a white, still representative of the Will. No need to seduce, attract, or solicit; this Will has been chosen by the previous Will. He moves into his spot, as a large block of ice shifts in the floe. Glacial emptiness, oppressive, his wife and daughter, impenetrable, large, no claim to please. There only the arctic will, its white face shielded by dark glasses, as if to filter, darken, shadow the tropical light and the color of its multitudinous, chaotic, brazen hoard of persons, insects, slums,its alive sufferings. This country with its marvelous people, its mad cars, its noise, its insane building, its amorous languors, its sinuously rich chic, its longings, its poverty: before the dark glasses of Geisel all seems to pass as before the blind. Prosperity flows to the chosen and to those who have more shall be given.

For the rest, the huge remainder, their time has not yet come. History still will not consent to touch so many ignorant, hungry, dying-early persons of this land. Those who are moved to concern and pity glow in the white military coldness with menacing fire—they must be destroyed. But then it is not uncommon to hear that torture has become “boring.” One brave old lady predicted that it would be replaced by murder, disappearance, gun shots in the streets. So it has proved to be. The idea of human sacrifice—a profane and secular purification rite, practiced in the name of progress, investment, and the holy “Growth”—has left the country a ruin. The land is rich in heroes created by the military Will.

A small card sent out by the family of a young student killed by the police:

Consummatus in brevi,explecit tempora multa

Tendo vivido pouco, cumpriu a tarefa de una longa existencia. Profundamente sensibilizada, a familia de JOSE CARLOS NOVAIS DA MATA-MACHADO agradece a solidariedade recebida por ocasian da sua morta.

(Having lived little [1946-1973] he accomplished the task of a long existence.)

The beautiful Rio landscape: thick, jutting rocks, which Lévi-Strauss thought of as “stumps left at random in the four corners of a toothless mouth.” Tristes Tropiques is to me the second most interesting book about Brazil.* Like the first, Os Sertoes (Rebellion in the Backlands) by Euclides da Cunha, it is scientific, philosophical, personal, a quest for the past, the country, for oneself, for Brazil, a quest carried out with an intense and almost painful concentration. The late (Lévi-Strauss) surely learned from the early (da Cunha).

The pictorial in Brazil consumes the imagination; leaf and scrub, seaside and backlands long for their apotheosis as word. Otherwise it is as if a great part of the earth lay silent, unrealized. Your own sense of yourself is threatened here and, thus, speculative description seizes the mind and by surrender to it a sort of tranquility comes. Strange that the landscape should be so drenched in philosophical questions.

Speaking of the towns in the state of Paraná, Lévi-Strauss writes:

And then there was that strange element in the evolution of so many towns: the drive to the west which so often leaves the eastern part of the towns in poverty and dereliction. It may be merely the expression of that cosmic rhythm which has possessed mankind from the earliest times and springs from the unconscious realization that to move with the sun is positive, and to move against it is negative; the one stands for order, the other for disorder. It’s a long time since we ceased to worship the sun; and with our Euclidean turn of mind we jib at the notion of space as qualitative.

Naturally, the military government has laid waste to the freedom and distinction of the University of Sao Paulo and the University of Brasilia, places scarcely venerable in terms of age and yet the best the country had to offer. At a freer time, Lévi-Strauss left France in 1934 and went to teach in Sao Paulo and from there to travel into the interior of Brazil, to follow his anthropological studies of various Indian groups. A French mind, ambitious, abstract, learned and yet almost violently open, as one may speak of violence at the moment when a mind and spirit assault and engulf their subject—this mind met the obstinate, dazed fact of Brazil. And immediately Lévi-Strauss conveys to us that sense of things standing in an almost amorous stillness, so piercing and stirring is the way Brazil seduces the imagination. Standing still—or when moving some- how arduously turning in a circle that sets the foreign mind on edge, agitates thought of possibility, of meaning, of past and future.

Advertisement

And always Brazil lies before you, even now, demanding to be named, to have its prophecy explicated, its dream and memory honored. Tristes Tropiques is literally a memory, written fifteen years after Lévi-Strauss left Brazil for the last time. It is a work of Brazilian anthropology, with its strangely and grandly speculative intensity about the Caduveo, the Bororo, the Nambikwara. But it is anthropology that lives like a kernel in the shell of Brazil. The trembling search for metaphor and the pull, always downward, to despair, to a weight of doleful contradiction: these tell you exactly where you are.

The body painting, leather and pottery designs of the Caduveo seem to Lévi-Strauss to represent a profound and striking sophistication. This elaboration is a part of his quest, his spectacular journey of self-definition:

The dualism, to begin with, which recurs over and over again, like a hall of mirrors, men and women, painting and sculpture, abstraction and representation, angle and curve, border and centerpiece, figure and ground. But these antitheses are glimpsed after the creative process, and they have a static character.

The Caduveo and their style of representation—hierarchical, still, symbolic in the manner of playing cards—will inevitably call forth in Lévi-Strauss’s mind a sense of “structural” kinship with things far away in time and place. But in the beautiful and bitter isolation of Brazil, the configurations are not only united by longing or innate design in man’s mind to the plains of Asia or North Dakota, they are united and standing in their setting. Here it is the town of Nalike, on the grassy plateau of the Mato Grosso. And we feel, so unlike a merely investigative work are these remarkable chapters, everywhere among the Indians an absorbed, special French investigator, creating in a hut next to a witch doctor his youth, his exemplary personal history and intellectual voyage.

Great indeed is the fascination of this culture, whose dream-life was pictured on the faces and bodies of its queens, as if, in making themselves up, they figured a Golden Age they would never know in reality. And yet as they stand naked before us, it is as much the mysteries of that Golden Age as their own bodies that are unveiled.

The mysteries of the Golden Age. When Lévi-Strauss traveled to Brazil in 1934 and later, fleeing the Nazi occupation in 1941, he found, one might say, in Brazil this great autobiographical moment, found it as if it were an object hidden there, perhaps a rock with its ornate inscriptions and elaborate declamations waiting to be translated into personal style. The book is a deciphering, one of many kinds. In one way it is a magical and profound answering of the descriptive and explicatory demand this odd country has at certain times made upon complex talents like Lévi-Strauss and da Cunha.

What is created is a work of science, history, and a rational prose poetry, springing out of the multifariousness of the landscape, its mysterious adaption or maladaption to the human beings crowding along the coast or surviving in small clusters elsewhere. Lévi-Strauss was only twenty-six when he first went to Brazil. He is far from home but the conditions are brilliantly right. He is in the new world and it is ready to be his as Europe, Africa, or Asia could not be. This newness, freshness, the exhilaration of the blank pages are like the map of Brazil waiting to be filled—this brings with it an intense literary inspiration. He is deep, also, in his professional studies; everything is right, everything can be used. When the passage grates it is still material. The two French exiles in their decaying, sloppy fazienda on the edge of the Caduveo region, a glass of maté, the old European avenues of Rio, the town of Goiânia: he speculates, observes, places, re-creates with a sort of water- fall of beautiful images.

It is the brilliance of his writing at this period that is Lévi-Strauss’s greatest, deepest preparation for his journey through the Amazon basin and the upland jungles. He is pursuing his studies, but he is also creating literature. The pause before the actual writing was begun, when he was forty- seven, is a puzzle; somehow he had to become forty-seven before the real need for the inspiration of his youth presented itself once more. It was all stored away, clear, shining, utterly immediate. Often he quotes from the notes he made on the first trip and always, seem to have brought back the mode, the mood also, and to have carried the parts written later along on the same pure, uncluttered flow.

A luminous moment recorded by pocket-lamp as he sat near the fire with the dirty, diseased, miserable men and women of the Nambikwara tribe. He sees these people, lying naked on the bare earth, trying to still their hostility and fearfulness at the end of the day. They are a people “totally unprovided for” and a wave of sympathy flows through him as he sees them cling together in the only support they have against misery and against “their meditative melancholy.” The Nambikwara are suddenly transfigured by a pure, benign light:

In one and all there may be glimpsed a great sweetness of nature, a profound nonchalance, an animal satisfaction as ingenuous as it is charming, and beneath all this, something that came to be recognized as one of the most moving and authentic manifestations of human tenderness.

In one way Tristes Tropiques is a record, not a life. There is nothing of love, of family, of personal memory in it, and little of his roots in France. At the same time, the work is soaked in passionate remembrance and it does tell of a kind of love—the great projects of great man’s youth. It is the classical journey, taken at the happy moment. Every step has its trembling drama; all has meaning, beauty, and the mornings and evenings, the passage from one place to another, are fixed in a shimmering, vibrating present.

And it is no wonder that Tristes Tropiques begins: “Travel and travelers are two things I loathe…” and ends, “Farewell to savages, then, farewell to journeying!” The mood of the journey has been one of youth and yet, because it is Brazil, the composition is a nostalgic one. At the end there is a great sadness. The tropics are triste. “Why did he come to such a place? And to what end? What, in point of fact, is an anthropological investigation?” How poignant it is to remember that often in places “few had set eyes upon” and living among unknown people, how often he would feel his own past stab him with thoughts of the French countryside or of Chopin. This is the pain of the journey, the hurting knock of one place against another.

Lévi-Strauss was in his youth, moving swiftly in his first great exploration, and yet what looms up out of the dark savannahs is the suffocating knowledge that so much has already been lost. Even among the unrecorded, the irrecoverable and the lost are numbing. The wilderness, the swamps, the little encampments on the borders, the overgrown roads that once led to a mining camp: even this, primitive still and quiet, gives off its air of decline, deterioration, displacement. The traveler never gets there soon enough. The New World is rotting at its birth. In the remotest part, there, too, a human bond with the past has been shattered. Tristes Tropiques tells of the anguish the breakage may bring to a single heart.

Breakage—you think of it when the plane lets you down into the bitter fantasy called Brasilia. This is the saddest city in the world and the main interest of it lies in its being completely unnecessary. It testifies to the Brazilian wish to live without memory, to the fatigue every citizen of Rio and Sao Paulo must feel at having always to carry with him those implacable Brazilian others: the unknowable, accusing kin of the northeast, the back-lands, the favelas. If you send across, the miles and miles the stones and glass and steel, carry most of it by plane, and build a completely new place to stand naked, blind and blank for your country (Brasilia, diminutive of the whole place, sharing its designation), you are speaking of the unbearable burden of the past. Brazilians are always fleeing their past and those capitals that stand for the collective history; they move from Bahia to Rio and now to Brasilia. This new passage the crossing, is one of the starkest in history. It is a sloughing off, thinning out, abandoning, moving on like some restless settler in the veld seeking himself. At last, in Brasilia there is the void.

It is colder, drearier in 1974 than in 1962. Building, building everywhere, so that one feels new structures are as simply produced as Kleenex, In every direction, on the horizon, in the sky, the buildings stand, high, neat, blank. Each great place leads to a highway. There are strictly speaking no streets and thus no village or corner life. Utter boredom, something like a resort which has no real season. A soulless place, a prison, a barracks. Rigidity, boredom, nothing. Try to take a walk around the main hotel. Even if there were a place you wanted for pleasure to get to, you must drive. There are no streets, you tell yourself again, as if perhaps it was something in Portuguese you misunderstood. Around you are roadways, wide, smooth, full of cars.

The military likes Brasilia. It is their Brazil. Nothing to do with the sad tropics, with the heart of history. So here in the deadness, in the agitating quiet of this city without memory, you remind yourself that this is the dead center. Everything indeed comes from this clean, silent tomb. There is nothing without its consent: no killing, no deaths in the street of young people brought back from Chile, no maiming, no interrogation and torture in the nude of Catholic lay women, seized in their night classes for adult workers.

There is no place to go. You came to see if it had changed and it had not, except downward. So back to the hotel room, on a red-dirt, desert plain. Relief comes in reading once more the great prose work, Rebellion in the Backlands, by da Cunha. It is a peculiar epic, military, mournful, seized with the old idea that there is a Brazil somewhere; it must be described. Its flowers, leaves, scrub, its thirsting cows and its drinking tapirs. And a tragic battle between 1896 and 1898, when an ill-prepared military expedition went out from the capital of Bahia to subdue a band of ragged religious fanatics.

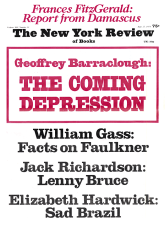

(This is the first of two articles on Brazil.)

This Issue

June 27, 1974

-

*

My quotations are from the 1961 (Atheneum) translation of Tristes Tropiques done by John Russell. A new edition based on the 1969 revised french edition and translated by John and Doreen Weightman was published by Atheneum in February, 1974.

↩