Those who know the Graham Greene of the critical essays he was writing in the Thirties will remember a sound thing he wrote about Sterne and Fielding, and his remarks on their “shell-shocked” Puritan predecessors in the revolutionary seventeenth century. (He was playing with an epithet he had taken from Trotsky in a very different context.) These readers will not be altogether surprised to hear that Greene had written a study of the most “shell-shocked” of all, John Wilmot, Second Earl of Rochester, a real example of the “burned out case.” The surprise is that the book was a substantial biography; that it has been lying for years unpublished in the library of the University of Texas.

This Life is, I believe, Greene’s only attempt at biography, and it has the originality, thoroughness, and alertness to affairs of conscience that one finds in his fictional manhunts. The manuscript had been rejected by his English publishers who feared the prosecutions for obscenity that angered writers in the Thirties: the vogue for the Restoration poets had begun, but the police and the customs officers were fouling it. He reminds us that John Hayward’s Nonesuch edition of Rochester’s verse had escaped only because it was issued to subscribers in a small limited edition; even so it was seized by the New York customs. Greene had enough trouble on his hands and lost heart.

Now he has looked again with some fondness at the manuscript and has not cared to make many revisions. He had admired the Life by Prinz (1927). He has since read Professor Pinto’s Enthusiast in Wit (1962) but has “no wish to rewrite my biography at Professor Pinto’s expense”—a scrupulous decision and a sound one, for Greene’s book has the tone of the Thirties. He had noted that the periods following violent upheavals in society have a common experience of disillusion and spleen. The writers of the Thirties, like those of the Restoration, knew what it was like to inherit the sins of their violent fathers and to be torn by conflicting tastes for the moral and the scabrous.

For Greene particularly, Rochester had the attraction of the gifted, tormented sinner, the man of split nature, divided between lust and love, familiar with remorse in his own self-sought ruin and unable to apply the salve of hypocrisy to a raw conscience. “Half devil, half angel,” a handsome dissipated charmer and fine poet, Rochester was a character of great complexity who offers dramatic guesses to any biographer. Greene saw a key in the conflicts of Rochester’s political inheritance. His Puritan mother had been married first to a Parliamentarian. He died. Her second husband, Rochester’s father, was in the other camp—a successful Royalist leader who had defeated the Roundheads in battle and was drinking hard in exile in Cromwell’s reign.

In anarchic times when the males are either killing one another or conspiring abroad, the preservation of family stability falls upon the women who become powerful in political long-headedness. Rochester’s mother was a shrewd, railing, domineering woman who kept her estate from destitution and boldly pushed the education and interests of her children. The young earl was precocious in intellect, and was brought up in the peace of the country and safe from the dangers of high politics. Because of his brains and title it was easy to push him into Wadham at Oxford at the age of thirteen. His father was an elusive conspirator in Paris who rarely saw his wife and family. When Puritan rule collapsed the boy was only fourteen. He was at once given a Master’s degree, gave up his studies, went on the Grand Tour, and in due time took up his father’s wild career with women and the bottle.

It is very likely a bad thing to allow the father one scarcely knows to become a myth; but if Rochester’s inheritance was bad there were other subtler influences. Greene has had the curiosity to look up an interesting note by Professor Pinto on the poet Sedley who was also at Wadham. The college, Pinto pointed out, was the seat of the famous scientific club that soon became the Royal Society and that would seem at first sight a guarantee of intellectual gravity and virtue. But in the Restoration science, as we know from Pepys and others, meant chiefly a passion for eccentric experiment, which the young men at Wadham genially distorted into experiments in wild behavior. The college produced a large number of the Restoration wits who felt they had a license to play with feats of sensibility and outrage.

At first the young man behaved well. He showed he was no coward by going to sea and taking his part in the scandalous disasters and almost accidental victories of the naval struggle with the Dutch. His bother was that it was no good being a spellbinding earl unless one had money. He was not rich. He was driven to the court, and at once captivated Charles II, and turned to the usual recourse of getting an heiress against the competition of richer men. A confident and reckless spirit of independence emerged in Rochester’s character. He had the cynicism of the Cavalier but also the idealism of the Roundhead; he was torn between the good sense of the countryman and the frenzy of the court.

Advertisement

In his pursuit of the heiress one sees Rochester as very much a postwar man playing hell with the established family system. First of all he organized a tactless “rape” in the Lovelace manner; she was rescued and he was sent to the Tower. But the heiress was something of a postwar girl. She fought her guardians and made up her own mind. It is almost impossible for us to grasp the special satisfactions of a marriage system unlike our own—for better or worse the girl settled for Rochester. He had at least attempted rape, a feat which had not occurred to the minds of more decorous or pompous suitors. Yet what she wanted was a quiet, solid country life even if for a lot of the time she was left on her own, while her husband made or lost his fortune playing boon companion and pander to the king whose mistresses he shared, and whom he flattered and insulted as the mood and the fumes of wine clouded his mind.

Rochester’s life was divided into three compartments. In London there was the court, the king, and the whores; in the country he had a house of his own for his horseplay and rake-hell life; for philosophy, poetry, repentance, his wife’s house not far off. (She had her own bolt-hole in another property she owned in Somerset.) Needless to say the rake adored his children.

Greene sees Rochester very much as the victim of his cronies who plied him with drink in order to enjoy his flights of wit and fantasy. The moral man was there, but in one sense—and especially in his poetry—he is a solitary. Talented men of his generation ignored the state and lived by literary wars of unexampled littleness and ferocity. His exquisite love poems rise from the sense of the evanescence of present love; its permanence, consolations (and its tortures) are in memory. He was capable of strangely appealing lines about the “kindness” or “sacredness” of jealousy—an idea that few have subscribed to—though to him kindness is the virtue of the faithless. In the experimental fashion of his time he exalted the “live-long minute,” sometimes known as the tenderness of lust.

Then talk not of inconstancy, False hearts and broken vows;

If I, by miracle, can be

This live-long minute true to thee, ‘Tis all that Heav’n allows.

Or

Dear, from thine arms then let me fly, That my fantastic mind may prove

The torments it deserves to try, That tears my fixt heart from my love.

At heart he has the poet’s arrogance.

Born to myself, I like my self alone,

And must conclude my judgment good or none…

Oh, but the world will take of- fence hereby!

Why then the world shall suffer for’t, not I.

That “fanatic heart” could be either Cavalier or Puritan. Or rather, as Greene says, the spoiled Puritan was self-tormented. Still the list of Rochester’s “frolics” is not pretty. He came close to murder in his rioting; he and his distinguished bravos—above all that ghastly rapist the Duke of Buckingham—behaved like vandals. Rochester was as savage as any moralist about the corruption of the court but he was part of it; and long before he died of drink, the pox, and goodness knows what else at the age of thirty-three, the angel had learned to hate and had become one of the most hated men in London. Greene, though in doubt, does not acquit him of a leading part in the famous beating up of Dryden: middle-class Dryden had the notorious weakness of wanting to be in with the aristocratic wits.

At the end of his short life Rochester seemed to repent under the ruthless interrogation of the eminent Dr. Burnet, though he put up a stiff atheistic defense against that divine and one cannot tell how far the repentance went. The poet who wrote the frightening poem “Upon Nothing” was a born actor and improviser. Still it is certain that he made very serious attempts to fit himself for the responsible public life to which many of the aristocratic blades were now turning at the end of the decade.

Advertisement

The Restoration scene comes to life in Greene’s hands, and while one is wondering why the self-tortured rogue should be so memorable as a poet and a satirist, Greene sees one or two of the reasons. Rochester was lashed into immorality because he was both an idealist and mountebank. (His pranks of disguise were notorious; with a sort of genius he learned the common tongue of London and could pass himself off, in brothel or market place, as beggar, huckster, astrologer, or quack.)

There is something new in his handling of language, as Greene points out, for he succeeded in the then original task of putting the easy speaking voice into verse usually glazed to the point of conceit. One hears the man not the school. From low life and from a court given to low life, or from his own peculiar isolation as a man, he learned to be pungently exact. There is violence yet the flash of a new precision in his handling of the lovehatred to which he was obstinately subject. See the lines in the poem on a passing fit of impotence in which the Puritan vilifies his organ:

When vice, disease and scandal led the way,

With what officious haste didst thou obey?

Like a rude, roaring hector in the streets

That scuffles, cuffs, and ruffles all he meets.

* * * But if great love the onset does command,

Base recreant to thy prince, thou dost not stand.

Worst part of me, and henceforth hated most,

Through all the town the common rubbing post,

On whom each wretch relieves her lustful ––

As hogs, on gates, do rub them- selves and grunt.

With this sinner Mr. Greene is a firm but charitable examiner. He has taken characteristic trouble with his sources and if it is a novelist’s book it is not novelized. It is a Rainbird production and has some good prints and portraits in color.

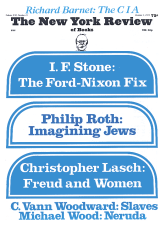

This Issue

October 3, 1974