New York belongs to Beverly. She was given two nightingales as a souvenir of the occasion. The Brooklyn Nightingale. Opera’s Cinderella. She is currently taking the curse of Culture off opera. But she is being lifted into myth herself. After all, the Swedish Nightingale, Jenny Lind, ascended to Olympus to the puffings of P. T. Barnum.

Horace Tabor’s first task, having built an opry house, is to escape it—next door, to the saloon. There he meets Baby Doe—who is, in the most memorable production of Douglas Moore’s opera, Beverly Sills. In The Ballad of Baby Doe Beverly is presented as an alternative to Adelina Patti; she is the opera singer for the hater of opera—as every red-blooded Horace Tabor is required to be. “My God!” a woman gushed at the splashy Met debut, “she’s made opera popular!” Among the penguins and spangled ladies, it seemed a joke worthy of peasant Verdi or peasant Rossini.

Presidents of the United States are, almost by definition, Horace Tabors. Both our recent and our current ruler had Beverly in to sing at the White House. Nixon had obviously been well briefed by someone (Len Garment?) and he sailed through greetings of the Sills family very knowledgeably—though her accompanist for the evening, Roland Gagnon, a distinguished musicologist, was dismissed as the boy carrying the sheet music. (“I expected a little better treatment from a fellow pianist,” Gagnon said later). Then, as one man reached Nixon in the receiving line, the President foundered. Mr. Yenta-lay? He looked around for help, and only Beverly was there.

“Why, Mr. President, this is Goeran Gentele, director of the Metropolitan Opera.”

“Oh yes,” the President recovered, “we thought your boss should be here, to see how you do.” Wink, from Gentele. Wink, from Beverly. They did not know, at the White House, that Beverly was famous for not having sung at the Met—a Rudolph Bing accomplishment. Not having Beverly was as careful a gesture as having Marian Anderson sing Ulrica—a historical wrong to balance the “historical right” of bringing on a superannuated saint to be the Jackie Robinson of opera. Gentele was already planning to rectify the historical wrong when he went to the White House—he deserves credit for the Sills debut at last accomplished under his successor.

President Ford may have been briefed, too—but he does not let prompting get in his way. He introduced her as “Beverly Stills, who can sing everything from Verdi ballads to Strauss operations.” Old Horace never spent much time at the opry—but good old Bev, who doesn’t put on airs, will understand. (And, in fact, she does—she defends the President every time this story is recalled in front of her: “He just had operations on his mind, because of his wife.”)

Beverly doesn’t put on airs. She likes to present herself as the proof one can get to the top without the Met. But she proved it by, at last, getting there. Of course, she was finally doing the Met a favor—a fact she made clear in various of her sweet but unmistakable ways. Still, it was a historical night, for her as well as the house. It was not just Beverly singing—she had sung hundreds of times a few steps away from the Met. But when she took those few steps, over the threshold, scalpers got up to a thousand dollars for the most desired ticket within memory. Beverly had finally made it—and so had the Met.

The new Met has had distinguished productions—despite its opening-night flop, which is also part of Beverly’s story (she was scoring a triumph in her back lane near the Cathedral, Baby Doe outdoing “Patty”). But the new Met lacked what the old one had in abundance. James McCourt wisely centered his novel, Mawrdew Czgowchwz, around the old Met. That house had ghosts—memories out of scale with reality, legends and myths. The new house has hitherto lacked that. Its legends begin now, with her; with the biggest night in the town’s memory. “The Siege of Corinth should be easy,” Julius Rudel cabled her from Paris, “after the long siege of New York.” It was the length of the siege that added just the right touch of revenge to make the evening legendary.

Opera is legendary or it is nothing. It sings legends and is legend. Its divas are not ordinary mortals. Beverly pretends to be one, and that is part of her appeal—but the pretense would not win if it were not so obviously at odds with fact. Strauss operations are unnatural. Opera voices are as contrived as a space satellite—they orbit earth, un-earthly. “The whole radical task is salvaging the woman from her Fame,” one of the cultists says in Mawrdew Czgowchwz—and he is one of those inflicting the Fame he would save her from. Beverly is Mawrdew of the novel—she has her own Secret Seven, her prior incarnations, her shrines, and the keepers of the shrines.

Advertisement

I do not mean that Mawrdew Czgowchwz is a roman à clef written for her. Mawrdew is Every-Diva. But so is every diva Every-Diva. They all began as Cinderellas and turned pumpkins into carriages to get to the party. Beverly’s party was just bigger than anybody else’s. The most enduring myth of opera is that of the outsider who “demythologizes” the fancy world of opera, Baby Doe who is an anti-star—and, of course, the star of our own opera.

“My God! She is making opera popular!”—this, after Geraldine Farrar, who had “Gerry Flappers” line the streets for her processions. After Galli-Curci, whose fans drew her carriage in traces. Beverly is called exceptional because she comes from Brooklyn. But Callas only resented being called a Brooklyn girl because she almost was. The stamp of St. Louis was as heavy on Helen Traubel as that of Brooklyn on Beverly. Dream up the caricature Irish cop, and you will find him married to Eileen Farrell. And the greatest diva of our century began in vaudeville as one of the Ponzilla sisters from Meriden, Connecticut. Opera’s reigning line has always been a royalty of Cinderellas, as befits music written by peasants. Everybody begins as an outsider to opera, since it is such an artificial world.

McCourt’s novel perfectly captures this artificiality, the note of a parallel (better) world built as an in-joke on the universe. The heroine’s last name is pronounced Gorgeous (which, after all, means “throaty”). She comes to her first fame as a singing Czech, cashing checks on her checkered past—which is even more complex than she realizes. Only after her breakdown does she remember that she is an Irish girl, the daughter of an earlier Bernadette Devlin. The queen at last becomes Cinderella, completing the myth. The novel multiplies in-jokes maddeningly. It teases and infuriates as divas do. It puts on airs. It talks in-alt’s, in gloriously halting starts, congested with its own expertise (which is, nonetheless, an invention). It contrives its own continual breakdown—like that of the character Ralph, who staggers around saying “I can’t believe her. I can’t be-lieve her. So I won’t.” The novel minces, and minces words, and makes itself a mockery. It is to divadom what Myra Breckinridge was to Parker Tyler movie nuts. Mawrdew is Myra—a self-creation made out of all the legends of her art.

Every diva has her worshipers. “I don’t want my every belch recorded,” Beverly says, in her best imitation of Belle Silverman, that Irish-lass prior incarnation that is partly invented. But her own Secret Seven record everything of hers they can. They compare her laughs from this opera and from that, and from a party where they taped her. If they haven’t caught a Sills belch yet, they soon will—one of the goddess’s toenails. Cultists devour their saint, everything about her, in holy communings. They want to know where she is, each moment; what she ate; what she is practicing, and where; why she is not singing some role they have dreamed her in. They bring offerings, and take away relics. One makes tapestries of her in various roles. Another turns Easter eggs into her face. They live amid Beverly dolls; they deaden her with fame, and then try to resurrect her, rescuing her from themselves.

The only real parallel is the courtly love of the twelfth century. Germans called that Frauendienst, and McCourt has aptly described his subject as divadienst. It is the art of distant intimacy. In the new world opera creates, everyone is Adam to the mind’s Eve, who is too familiar to need ravishing, brought close by a voice that fills a house as easily as a head.

Opera is a parlor trick too big to be played in any but the largest house—which is why there is a magic to the Met one cannot get next door. Beverly makes fun of the idea that a voice should be judged by the place where one hears it. But magic takes props, and preparation—and lots of magician’s helpers. It takes hoopla and stars. Rossini knew that—he was a bigger god than any diva of his time, and got the full diva treatment. Siege of Corinth, which cannibalizes many of his earlier operas, went through three stages. The New York Times critic Peter Davis—a black object of hatred to Beverly fans, because he has refused, all these years, to fall down and worship her—damned the recording of Siege (with the same conductor and cast as the Met opening’s), because it sticks to no single one of the three Rossini versions. Thomas Schippers took the third version and reinserted some of the spectacular stuff that could not be sung by the third cast. This kept the pyrotechnics of the first version, the spectacle and politics of the second (which played on the Parisians’ Byronic sympathy for Greece), and the adaptability of the third version (which went back into Italian and was not geared to the special theatrics of Paris). The result is a knockout, which became the Bev and Shirley show on opening night (Beverly getting a five-minute ovation in act two, Shirley Verrett a fourminute one in act three).

Advertisement

I asked Beverly about the Davis review, and at first she would say nothing more than this: “I think Mr. Schippers is as good a musicologist as Mr. Davis.” Her husband said, “Peter Davis—who’s he?” (Like Evelyn Waugh’s question—“Edmund Wilson; is he an American or something?”) But opera lovers live on bickering; and even Beverly, who tries to keep clear of the battle, will finally, if one keeps at her, reveal the Goddess Scorned: “I think some so-called musicologists are like men who talk constantly of sex and never do anything about it.”

The funniest line in the Davis review is creatively wrong; it suggests a truth while it keeps itself innocent of truth. He says that putting the tough cabalettas back in Siege is “rather as if a conductor decided to insert a few arias from Verdi’s Ernani into his Falstaff to spruce up the evening.” Rossini never traveled the long distance from Ernani to Falstaff. His course of development from his mid-twenties to his mid-thirties—from, say, Tancredi to Siege—does not span the creative progress Verdi made from Nabucco to Aida. The later breakthrough to Otello and Falstaff is something Rossini never attempted—and that Verdi himself would not have tried but for the inspired heckling of Boito. Rossini stopped composing at age thirty-seven, a thing that has always puzzled scholars. They tend to forget Verdi’s similar retirement after Aida. Rossini simply had no Boito.

Rossini was the most natural musician ever. For him to stop composing struck contemporaries with amazement; it was as if he had stopped breathing. That is probably one reason why he did it. The magician must serve up ever bigger miracles, new tricks (as he knew—he privately called his late solemn mass “the monkey’s last trick”). By 1830 it must have seemed to Rossini that the only new trick left that would be bigger was no trick at all—a new puzzle for the cultists: the god become a sphinx. He had ended with a trick that made his silence all the more resonant: William Tell. By then Rossini’s melodic springs were not running dry—though he was asking new questions about his own tunes. His contemporaries heard a new interest in harmony and orchestration—a perception that seems misguided to us, who look back over and around and through Wagner.

The ensembles of Siege are impressive; but their trick is basically as simple as the “Fredda ed immobile” of the Barber. To a slow rhythmic pulse, within a clear harmonic frame, scraps of each person’s thoughts are run through parallel labyrinths. But a trick worked well enough will go beyond itself, the magic stunning the magician. And that is what is happening in the act one trio of Siege. The labyrinths are more complex, kept parallel but at a greater distance from each other. Three people are singing the same words, but they mean radically different things to them all, and the three never meet—they only blend on the very last (misleading) word: rigor. As they seem to converge but don’t, they also threaten to break out of the careful frame, but don’t.

The third version of Siege was performed the same year as William Tell—and the greatness Rossini was reaching for in Siege he laid hands on in Tell. To go beyond that trick would call for something drastic, for starting all over again—he had exhausted the forms he started with. In the future he would no longer be cannibalizing his own early work, but canceling it. He had to undo himself, build himself all over again, to a new plan. That meant a doubling of self-doubt—and then a tripling of self-confidence, to counter the doubt. Verdi (barely) made just that kind of withdrawal and return. Rossini simply withdrew—which takes its own kind of wisdom and self-knowledge. His later trifles and teasing private compositions prove that he would have been doing something very different if he had gone on. Instead of treating a new world, he retired as the largest deity in the old one.

What’s left?” I asked Beverly the day after her Met debut. She was very tired, and wondering what the hell to do with the nightingales (one from Barbara Walters, one from Danny Kaye).

“Nothing. I’ve done it all.”

“Any regrets?”

“That my father was not there.”

That day, all the challenges looked past her—but her cultists and her critics (the adorers of rival deities) will find some for her. She can only do impossible things now. The gods are captive to their own power. McCourt wafts Mawrdew off, at the end of his novel, to a timeless Watteau picnic; but cultists of the novel (it is a diva in its own right) are already whispering that he will bring her back. The only twilight for a Mawrdew is one haunted with legends of return. “Donne, donne, eterni Dei, chi v’ arriva a indovinar?“

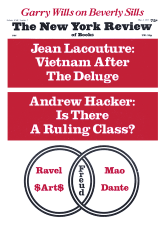

This Issue

May 1, 1975