Washington

1

Is Richard Nixon really in San Clemente? Or back in the White House? The Mayagüez affair was handled with that unforgettable Nixon touch. The overwhelming concern behind it was not the safe recovery of the ship’s crew but a fear that prolonged negotiations over it would be “humiliating,” would show us to be—in Nixon’s plaintive phrase—a “pitiful helpless giant.” This fear of impotence was the dominant Nixon neurosis in foreign policy, and its marks are so clear in the White House response to the ship seizure as to make one wonder who’s really in the Oval Office. Ford’s public relations men are trying to sell him as a second Truman, but he’s unmistakably vintage Nixon; the bottle may carry a new label but the content is from the same cru.

Ford’s main victory in the Mayagüez affair was not over Cambodia but over Congress. The most important casualty was the War Powers Act of 1973. Nixon’s bitterest defeat in foreign policy was the vote with which Congress overrode his veto of that act. What Nixon could not block, his successor—in one swift stroke—has emasculated. The act requires a president, before sending troops into action, to “consult” with Congress. The Mayagüez affair has reduced this salutary restraint on trigger-happy executives to a dead letter.

What does consult mean? The word may be imprecise, in that it leaves open the question of who will make the final decision, and how; but it is not without meaning. Webster’s defines it, “To seek the opinion or advice of another; to take counsel; to deliberate together; to confer.” In the Mayagüez affair congressional advice was neither invited nor taken.

A select handful of congressional leaders—mostly the old-boy network—were told; they were not consulted. With Ford’s version of consultation, the Imperial Presidency of Nixon is back, full blown. The constitutional war-declaring power of Congress is again in deep freeze. Once again, in Kissinger’s word for it, the executive can be “flexible” and once again the country may be plunged into military adventures in Asia or elsewhere without full debate or even full knowledge of the facts. The Cambodians may not have been frightened, but we had better be.

With the old Nixon-Kissinger finesse, Ford went through all the motions but reduced consultation to a sly caricature. The decision to engage in military action was arrived at in a National Security Council meeting on Tuesday morning, May 13. But “consultation” with congressional leaders did not begin until 5:55 PM when the troops were already in motion, and only an hour and thirty-five minutes before the first shots were fired.

When the act was passed, everyone assumed not only that “consultation” would be before decision but that it would involve direct contact with the president. But Ford did it with a series of telephone calls. The calls were made by White House staffers so far down the bureaucratic totem pole that few newsmen in this town had ever heard of them.* The form “consultation” took was the reading of a formal statement announcing the president’s decision; the procedure left as much room for discussion with the decision makers as if it were done by office boys or the White House telephone operators.

Even according to the official chronology the last call—to Senator Eastland—was at 8:20 PM, just ten minutes before we began our glorious little war. In fact both Eastland and House Minority Leader Rhodes said at one point that they weren’t notified until after gunboats had been sunk. This is an ominous precedent.

Congress raped as easily as it did in the Tonkin Gulf affair. This time there was no Morse and there was no Gruening to speak up sharply, clearly, and unequivocally. Johnson’s Tonkin Gulf resolution at least gave Congress a chance to vote. Ford’s selective phone calls—there were just eighteen of them—saved the Senate’s demoralized doves from having to stand up this time and be counted.

McGovern, however, on May 14 called the administration’s actions “not a policy but a spasm conducted by officials who want to prove their toughness.” The questions he raised were not only ignored, but he was wrongly quoted in The Washington Post two days later as saying, after the crew was released, “I’m glad he [Ford] did it.” He made no such statement. Nelson of Wisconsin was also clear and sharp in opposition. Kennedy was muted in his reaction, and Jackson first attacked the military moves as provocative and then, after the crew’s release, gave Ford “high marks.”

Among the outstanding casualties were senators like Javits, who had sponsored the War Powers Act and looked the other way when it was being destroyed. Senators Case of New Jersey and Church of Idaho, who had written into successive appropriations acts specific bars against the introduction of American military forces into Indochina, now felt that they did not apply!

Advertisement

Their position circumnavigated their own statute and came to rest at the same point as the White House, in the proposition that the president has inherent powers, irrespective of congressional prohibition, to protect American lives and property abroad. This was the classic excuse for American imperialism in Latin America before World War I and the seed from which the Imperial Presidency grew.

2

The softening-up process had begun before the seizure of the Mayagüez. The week before the incident somebody (and who but Kissinger?) had been directing a Nixon-era “con” job on the Hill. In the House the results surfaced by coincidence the day of the seizure in a statement from fifty-six congressmen hitherto regarded as unflappable critics of military and diplomatic nonsense. They released for publication a bit of Germanic military-Hegelian mysticism (very much à la Kissinger, on the day he wears his field marshal’s hat) saying, “Let no nation read the events in Indochina as the failure of American will.” Les Aspin of Wisconsin led this extraordinary procession of suckers; he has been making a reputation picking at million-dollar nits in the Pentagon budget yet he swallowed whole a line that State and Pentagon have been putting out to get us ready for a new Asian adventure, this time quite possibly in Korea again.

Among the liberal fall guys who joined him were Bingham of New York, Reuss of Wisconsin, Brademas of Indiana, Ron Dellums of California, Mrs. Sullivan of Missouri, Harrington of Massachusetts, Moorhead of Pennsylvania, Frank Thompson of New Jersey, Walter Fauntroy of Washington, DC, and Andrew Young of Georgia.

Implicit in the statement is a new revisionist history of Vietnam which will come in handy if and when we find ourselves once more bombing the Asian mainland, crossing the thirty-eighth parallel in Korea, or fighting guerrillas to keep Marcos in power in the Philippines. Can anyone believe that we learned the lesson of Indochina when fifty-six liberals sign a statement with a picture as bland as any Nixon ever painted of the prolonged agony that military and diplomatic folly imposed on the Indochinese and ourselves? “During the late 1950s and early 1960s,” their statement said, “we set out to help a government in Saigon. We did so with a high sense of national purpose, but tragedy followed.” And now, it added, that “the war in Indochina is removed as a reason for divisiveness in our society, we believe the US will be more likely, not less, to honor longstanding ties and treaty commitments.” That spells K-O-R-E-A. Are we to have no cause for reflection? Must they enlist so soon?

The real demonstration of national will was the awakened humanity and good sense that forced the retreat from Vietnam. Should America ever be attacked, its people will never lack the will to defend themselves. But they must also have the will to protect themselves and their resources and world stability from adventures motivated by considerations of military “face” and imperialist inertia. Peaceniks who do not see this are frauds, ready to fold up not only in any emergency but even before one happens.

A similar “con” and a similar flabbiness were on display in that supposed citadel of pacific good sense, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. On Wednesday afternoon, May 14, two days after the seizure, its members wrangled all afternoon and finally approved unanimously (where was McGovern?) a resolution of studied ambiguity if read closely, but a public relations plus for the White House. In the headlines next day and the news summaries it figured simply as an expression of support for the bombing attacks which had begun the night before.

It is an index of smart executive footwork that formally this expression of support was not a Senate resolution so that it would not have to be sent to the full Senate for a full debate and vote. So anxious was the Administration to avoid even another possible Tonkin Gulf twosome of dissent, ringing the alarms in full view of the country. The “resolution” was put forward by Sparkman, the toothless old tabby cat who succeeded Fulbright as chairman. Its prose style was his, but the hand behind it was Kissingerslick.

Sparkman opened the meeting by saying that he thought the committee should have been consulted under the War Powers Act “prior to the decision to take retaliatory action” and that telephone calls the night before to two members did not constitute consultation. Yet the affair ended with a resolution not of protest but of support! Mansfield, an occasional volcano which too often seems extinct, took part in the charade and then outdid himself in evasion on ABC’s “Issues and Answers” the following Sunday. If only the Pentagon could face such opponents in battle, our Asian “incursions” would never end in defeat.

Advertisement

Was the Mayagüez affair an accident, an “incident,” or a provocation? Who knows. But Freud would say that accidents tend to happen to those who unconsciously seek them. Like individuals, bureaucracies often seem to stumble into the “incidents” they secretly desire. Kissinger, who talks reason but acts out a Bismarckian logic, has been grumbling off the record ever since the Thieu debacle about the need for an occasion to prove US “toughness.” He has a way of standing outside himself with a self-depreciatory humor that deflates criticism by anticipating it. Thus at his press conference May 16 he said he was not turning the Mayagüez rescue “into an apocalyptic affair” or “looking for an opportunity to prove our manhood.” But this is exactly what he has been doing though he may deny it. One place in which this came out publicly in a direct quotation was after he told Tom Braden (see the latter’s Washington Post column April 12), “The US must carry out some act somewhere in the world which shows its determination to continue to be a world power.” Except for Liechtenstein or Luxembourg we couldn’t have picked a safer target on which to demonstrate our toughness.

Among the other indications of how little we have learned from recent experience is that nobody suggested that the CIA might very well have been carrying on “dirty tricks” in Cambodia after Lon Nol’s fall. Indeed there have been indications that agents had been dropped with transmitters for fake broadcasts to spread “disinformation.”

It should surprise no one, after the Pentagon Papers, if CIA sabotage squads had been landing in Cambodia. It should at least be said that a country which engages widely in such activities and even boasts of them must expect its shipping to be watched with suspicion. But from a Congress in which both houses have been reverberating with attacks on CIA practices there hasn’t been one astringent observation of this kind to temper US nationalistic resentment over the seizure with a little cooling reflection.

It is against this background that one must assess the failure of US intelligence to warn US shipping in an area where several other ships had been seized and examined. US agencies like NSA have been monitoring all Cambodia’s internal and external communications closely since Lon Nol fell. The CIA’s Foreign Broadcast Information Service, which circulates to a select list in the capital, monitored the seizure of a South Korean vessel May 5 in the same waters and next day reported that the South Korean government had warned its shipping to stay clear of the coastal zone. Yet despite a State Department regulation which required such warnings, none was issued by any US agency until after the Mayagüez got into trouble.

When Kissinger was asked about this at his May 16 press conference, he replied that “insurance companies had been notified.” But the New York Journal of Commerce, which specializes in shipping news, carried a front-page story May 19 rebutting Kissinger and quoting the head of the American Institute of Marine Underwriters as denying any such notification. Ford’s cry of “piracy” was overkill. The Mayagüez was eight miles off a Cambodian island. Just one week later we seized a Polish vessel off San Francisco only 1.2 miles inside our own twelve-mile fishing limit.

3

The Mayagüez affair grows murkier from day to day. A key question—the danger that we might have killed our own crewmen in sinking those Cambodian gunboats—was put to Kissinger at the very opening of his May 16 press conference. Kissinger acknowledged that our own men might have been on board but said, “We had to balance this…against the risk of their being taken to the mainland…. We wanted to avoid a situation in which the United States might have to negotiate over a very extensive period of time.” So we preferred the risk of killing our own men to the risk of a “humiliating” negotiation. That admission has yet to register on the national consciousness.

Why have the casualty figures been treated in true Tricky Dicky style? The Pentagon had been insisting that there was only one known dead. But the captain of the Mayagüez when he reached Singapore May 17 told the press there were seven dead marines “on ice” on board the Wilson Thursday morning when the operation still had twelve hours to go.

Next day on ABC’s “Issues and Answers” Secretary of Defense Schlesinger was asked about this. He said ‘he thought the captain was in error but he revised the casualty figures upward to five dead, sixteen missing, and seventy to eighty wounded for a grand total of close to 100. How long would we have had to wait for those revised figures if the captain had not put the Pentagon on the spot? A day later the Pentagon—perhaps under pressure from the White House—took the extraordinary step of overruling its own secretary and revising the number of wounded down to forty-nine. It now said some wounded were just “headache” and “band-aid” cases. But next day the Pentagon increased the number of those killed in action to fifteen, reduced the number of missing to three, and increased the number of wounded to fifty. That the Administration had been playing a self-serving numbers game with the casualty list all along became obvious on May 21, when it revealed that another twenty-three men had been killed in a helicopter crash while embarked for “possible use” in the Mayagüez operation.

What is the truth behind the leaks, apparently from the Pentagon, that Kissinger wanted B-52 raids on Cambodia in retaliation for the ship seizure, and proposed the Phnom Penh airport as one target? These surfaced in a column by Joseph Kraft on May 18 and one by Evans and Novak next day, and both gave the Pentagon credit for moderation.

The leaks found support in a Baltimore Sun dispatch May 19. It said an “official,” and one guess is enough to identify him, speaking on board the plane taking Kissinger to Vienna “expressed anger” over these reports. He protested that a president must be able to look at all options “without having someone reveal the alternatives in order to take credit for preventing them from being implemented.”

How close did we come to repeating the kind of bloodbath by bombing we imposed on Hanoi for Christmas 1973? In this readiness for overkill, this instinctive resort to terror, and the self-congratulatory jubilation in so puny a victory over so helpless a foe we see again the stance of Lyndon and Dicky. For a power which claims responsibility to maintain a balanced world, this is not a well-balanced way to act. If private persons acted out the silly ups and downs of the last few weeks in official Washington they would be regarded as manic-depressives.

Last time the war ended in Korea twenty-two years ago, Nixon rushed out to the Far East to keep the French war going in Indochina. Now that peace has come to Indochina we are “signaling” that we are ready if necessary for war again in Korea. The purpose of our “toughness” in Cambodia, the United States is being told, is to deter North Korea.

A headline in the Baltimore Sun May 20 reports, “North Korea says United States threatens nuclear war,” and that indeed is a logical conclusion from Secretary Schlesinger’s interviews in US News and World Report May 26 and on ABC’s “Issues and Answers” May 18. Schlesinger told US News that if the North invaded the South we would be more “vigorous” in attacking than we were last time in Korea or in Vietnam because a conflict that lasts too long “is bound to lose the support of the American public.” So Schlesinger wants less restraint this time. Last time our bombers leveled just about everything standing between the thirty-eighth parallel and the Yalu. The only restraint was not using the atom bomb.

This is dangerous talk. We are already suffering from a serious depression and inflation due to the Vietnam war. Another War in Asia could easily wreck the economy. Last time we went into Korea to “contain” China and Russia. Now the Pentagon line—believe it or not—is that we must be strong in the Far East to protect China!

“Do you mean,” Schlesinger was asked by US News, “that the Chinese, who for years have tried to drive the US out of the western Pacific, now are bent on keeping us there?” Schlesinger answered, “I think that is correct.”

But last time Chinese “volunteers” intervened when we reached the Manchurian border and pushed us back to the thirty-eighth parallel. It is hard to believe that China would not react again in a hostile manner if the North were occupied and US forces came up to the Yalu. China may—within limits—see the US as a counterweight to the Soviet Union, but a Korean war would again risk a war with China.

Do the American people want to drift—as we are beginning to—in this direction without full debate and understanding of what may be entailed? Almost all of the postwar conflicts have been bred by countries divided after World War II. Germany, China, Vietnam, and Korea have proven to be hotbeds of tension and war.

The problem is not just to deter the North from an invasion but by patient diplomacy to tackle the problem of this division and try to defuse the menace of a new Korean war. Two rigid regimes glower at each other across that border and can again threaten to draw the superpowers in. Washington, Peking, and Moscow, and above all Tokyo, have an equal interest in preventing the outbreak of a new Korean civil war.

The danger on our side lies not only in possible attack but in the internal situation in South Korea. The day that the Mayagüez was seized the Park regime used the danger from the North—real or fabricated—as an excuse to do what Syngman Rhee did a quarter of a century ago before the last Korean war. It clamped down completely on opposition of any kind and ended all democratic liberties. One of the lessons of Vietnam, where the Diem dictatorship and later Thieu’s followed much the same course, is that such moves undermine the regime they were intended to protect.

We still don’t know just how or why the other Korean war started and we should be on guard lest Park, in desperation, stumble into war in order to assure himself of American support if he fears that he might be overthrown. Thirty-eight thousand American troops in Korea are his hostages.

On both sides of the border, fanatical dictatorships, equally ready to exploit war alarms for domestic purposes, can drag their big power patrons to disaster without anyone ever knowing what really happened to set the peninsula ablaze. Do we want to get into another Korean war? Isn’t it as important to deter Park as to deter Kim II Sung?

It is time to recall that the terms of the US-South Korean Mutual Defense Treaty of 1953 are not automatic. They do not bind the Congress blindly to follow the executive into some new Korean “police action.” Article III provides that in the case of “armed attack” each signatory will “act to meet the common danger in accord with its constitutional processes.” This was drafted to assure Congress that it could not be sidetracked and would retain the final decision.

A quarter century ago, after the agony of the first Korean war, we said “never again” to war on the mainland of Asia. We forgot this in Indochina and we may be on the way to forgetting it again in Korea. The delusions of swift and surgical victory by air power are evident again in the Defense and State Departments. Let’s stop, look, and listen—debate and negotiate, and eschew bluster for diplomacy before it’s too late.

—May 21, 1975

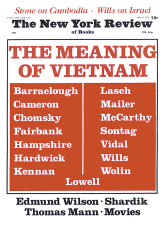

This Issue

June 12, 1975

-

*

Since their valiant efforts, according to Ron Nessen, produced “a strong consensus of support and no objections” (would the troops have been recalled if they hadn’t?), we give their names here for the future historian, since only one newspaper seems even to have printed them. The triumvirate of presidential stand-ins were Max Friedersdorf, Bill Kendall, and Pat O’Donnell. “The President,” the Washington Star reported from the White House Wednesday afternoon, May 14, “did not speak personally to any members of Congress but their [the eighteen congressional leaders’] comments were conveyed to the Oval Office by White House aides.” Thus all was constitutionally carried out à la rigueur. Even Nixon never staged better comedies.

↩