RUSSIA

The recently convicted Russian worker and writer Anatoly Marchenko has arrived at his place of exile in Siberia. This news, which has just reached his wife Larissa Bogoraz, ends her fears that he might have died during the grueling deportation from Moscow to the small town of Chuna near Irkutsk. For six weeks after he was given a four-year sentence she had received no news of him. Before his dispatch he had declared that he would maintain indefinitely a hunger strike begun on February 26, the day of his arrest, and the prison authorities were already force feeding him.

But when the deportation started on April 12, the guards refused, contrary to law, to recognize his hunger strike, and so also refused to force feed him. His last reserves of strength quickly ebbed away and he collapsed unconscious. When revived, he realized that he would soon die if he continued his eight-week strike. On April 20 he broke his fast. A month later, on May 21, he arrived in Chuna.

The Marchenkos are pursuing their efforts to emigrate, despite the exile sentence. They have appealed to President Podgorny to facilitate this by quashing the sentence as illegal. A campaign in their support has been organized in the US, Britain, Holland, and elsewhere by humanitarian, trade union, cultural, and religious organizations. In Britain the miners’ leader Lawrence Daly has been especially active, and in America the union leader Albert Shanker last year personally invited the Marchenkos to come to the US.

At the same time that the news of Mr. Marchenko’s survival has reached the West, so too have a transcript of his trial and related samizdat documents. They reveal not only the long vendetta which the Soviet secret police, or KGB, have been conducting against Mr. Marchenko, but also the KGB’s remarkable obsession in forcing would-be emigrants among Soviet dissenters to apply for emigration not to Western countries but, exclusively, to Israel.

This practice has been attacked in a recent statement by Dr. Andrei Sakharov, who explains it by the authorities’ desire to make “anti-Zionist and anti-Semitic” propaganda by lumping Jews and dissenters together and presenting them as disloyal citizens who are concerned only to escape to Israel. Dr. Sakharov points out that because Mr. Marchenko received Invitations from the US he refused to apply for emigration to Israel. He praises Marchenko’s “consistent stand in not yielding to the KGB even when preparing to emigrate.”

The documents also reveal that Mr. Marchenko was first urged to emigrate by the authorities as long ago as 1967, when he was only twenty-nine. This was after he had spent eight years in forced labor camps and described them in a book, My Testimony, which was later translated into many languages. A KGB official told him then that if he did not emigrate he would be imprisoned, though not—formally—for writing the book. Marchenko ignored this threat, and took part instead in the incipient human rights movement. A month before the Warsaw Pact powers invaded Czechoslovakia he warned the Czechs, in an open letter, of their impending fate. Then, seven months after the KGB’s threat, he was arrested. He spent three more years in the camps.

Only in 1973 did Marchenko become active again in the human rights movement. The KGB’s response was to search his house in Tarusa, confiscate his writings, and, in May 1974, impose an “administrative surveillance” order on him. Since this order—the rough equivalent of a South African banning order—was not imposed by a court, it was, in the opinion of independent observers, probably illegal. In any case it meant that Marchenko could not be out of his house after 8 PM, could not visit public places or restaurants, could not leave town without permission (which was usually refused), and had to report weekly to the police.

In August the police methods of applying these restrictions became so severe that Marchenko regarded them as wholly illegal and announced that he would no longer observe them. In December he wrote to President Podgorny that he wished to renounce Soviet citizenship and emigrate to the US. Called to the visa office two weeks later, he was advised to apply for Israel: “If you insist on the US, you’ll end up being sentenced for violating the surveillance restrictions.”

On January 13 criminal proceedings were instituted on this basis. At the same time it was made clear to Marchenko that he would be allowed to leave for Israel at any time. On February 25 he submitted his final emigration papers, but his desired destination was still the US. The next day he was arrested. Declaring a hunger strike, he refused to give evidence on the grounds that he would be tried, formally, for violations of the surveillance restrictions, but, in reality, “for my civic actions and my intention to emigrate to the US.”

Advertisement

The trial—on the predicted charges—took place in Kaluga on March 31. Entrance to it was free, and twenty of Marchenko’s friends and relatives, including Dr. Sakharov, attended. When Marchenko was led in, “he looked in bad shape, his face was haggard and exhausted, his lips dry and swollen, his arms handcuffed behind his back.”

Marchenko asked to be defended by his wife. Judge Levteyev refused this request and imposed on him an official lawyer. In protest at this, and at the removal from him of the necessary materials with which to defend himself, Marchenko refused to participate in the proceedings. He only reserved the right to a final speech.

Police witnesses then gave evidence of Marchenko’s alleged violations of the surveillance restrictions. Some of this evidence, according to his relatives, was fabricated. But the court refused to call these people as witnesses, despite the fact that their evidence—even in the view of the defense lawyer—would have cleared Marchenko on one of the charges. On the other hand, a gas board official, his last employer, stood firm and gave him an excellent character reference.

During the interval, while plain-clothes men harassed them, Marchenko’s friends discussed—but rejected—the idea of a collective walkout to protest against what they regarded as “a kangaroo court.”

Marchenko then began his “final speech.” He pointed out that as his writings and “antisocial activity” figured in the case against him, even though irrelevant to it, he had the right to explain why he had written My Testimony and raised the issue of the forced labor camps: “I interceded for people interned in inhuman conditions, who had no possibility of interceding for themselves…. I appealed to the Soviet Red Cross. They replied: ‘That’s how it has been, and that’s how it will be.’ “

This theme annoyed Judge Levteyev: “Don’t use your speech to denigrate Soviet authority!”

Mr. Marchenko continued: “Although I considered the surveillance order illegal,…I thought of my family and didn’t, therefore, break its rules…. I stopped observing it only when finally convinced that the aim was severe harassment of me. From late summer all my requests connected with looking after my family were refused. I asked permission to collect my aged and also illiterate mother from the station in Moscow—refused. To visit my ill child in Moscow—refused.” The last straw was the refusal to allow him to take his son for urgent treatment for scarlet fever.

Mr. Marchenko said he regarded his decision to emigrate as “capitulation before the all-powerful KGB.” Now the KGB was “carrying out its threat” to sentence him if he refused to choose Israel.

For the last part of his speech, which was applauded by the audience, Mr. Marchenko was too weak to stand. “I regret nothing,” he said. “I do not regret that I was born in this country, and born a Russian. But, thinking of the fate of my two-year-old son, I appeal to people throughout the world, and ask all those who can do so to help me and my family to leave the USSR.”

KOREA

Kim Chi Ha, South Korea’s leading poet, was rearrested on March 14 for alleged violations of the anticommunist law and is now on trial. The charge of sedition against him carries the death penalty. Recent executions in Seoul and the current attempts by the regime to discredit Kim in Japan and the United States suggest that the government not only intends to convict this writer but to silence him.

Kim’s work has expressed the feelings of many who are suffering and being persecuted in Korea, whether they are impoverished peasants or dissident professors or Catholic protesters. His poetic imagery is gritty and drawn from ordinary Korean life. In his satire, which can be ribald and scathingly funny, he has not been afraid to call attention to corruption and repression. He is a poet with a rare power to reach a great many Koreans, and to alarm the regime.

Kim Chi Ha was born in 1941 in Mokp’o, a port city in the traditionally rebellious South Cholla province. He emerged as a student leader in 1964 and 1965 during the large demonstrations against normalizing relations between the Republic of Korea and Japan. Sick with tuberculosis in the late 1960s, Kim published his first major work, Five Bandits, in 1970. It is a satire about the robber baron leaders of the Park regime, “the Tycoon, the Assemblyman, the Government Official, the General,…each endowed with a robber’s sack as large as the balls of a bull.” Kim was arrested, detained without trial for several weeks, and subsequently released on bail.

Kim published his poem “Groundless Rumors” in April 1972. It included an account of a simple peasant victimized by confidence men in Seoul, as well as a riotous scene in the skyscraper hotel (owned by the director of the Korean Central Intelligence Agency) where a fire on Christmas Eve, 1971, caused many to die because there were no fire escapes. Such social comment was anathema to the regime. On April 12 the Korean CIA placed Kim under house arrest at a sanitorium in Masan; the authorities ruled that the poem violated the anticommunist law. However, an international campaign resulted in Kim’s release from detention in July 1972.

Advertisement

On October 17, 1972, Park Chung Hee declared martial law, suspended the constitution, and dissolved the national assembly. The new Yushin Constitution promulgated in November made Park president for life, curtailed civil rights, and allowed him to rule by fiat. Numerous emergency decrees followed in response to student and intellectual dissidence. The Mokp’o police arrested Kim at dawn on April 25, 1974, for helping to finance student demonstrations earlier that month. Kim described an episode with several old fish mongers as he was being led away:

Faces exhausted by life, burned black from the sun, the women stared at my handcuffed figure as at a thief or a burglar. Yet those very expressions were signs of deep sympathy, for they saw me as one of their own pathetic kind, crushed by the same poverty and bearing the same cruel fate. In those sympathetic looks I discovered for the first time the warm welcome of my native town.

In July 1974 a military tribunal sentenced Kim to death. He had admitted giving funds provided by Catholic bishop Daniel Chi-hak Soun and others to student demonstrators. After protests against the severity of the penalty by prominent intellectuals including Jean-Paul Sartre, Louis Malle, Noam Chomsky, and Oda Makoto, Kim’s sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.

During the trial Kim’s lawyer, Kang Sin-ok, had the temerity to compare the proceedings to those held in Nazi Germany. On July 15, before the trial ended, KCIA agents abducted Kang for interrogation. In September Kang was convicted of violating the very presidential decrees against which he had defended Kim Chi Ha. Kang was sentenced to ten years in prison and barred from practicing law until 1994.

In February 1975 Kim was released from prison under a conditional amnesty prompted largely by fears that the US Congress would cut aid. In spite of government threats to put him back in prison if he spoke out, Kim published a long three-part essay entitled “Asceticism 1974” in the Donga Ilbo (this was during the brief period, now ended, when that newspaper could publish freely). He wrote about the torture of prisoners, and described the KCIA interrogation center.

Section 6 of the CIA—those barbarous, rectangular, weird-colored rooms. Dismal rooms constructed so that upon waking from a bad dream and seeing the blindingly bright walls one is immediately dragged back into the world of nightmares. Rooms of terror inaccessible to a single pleasant memory or ray of hope. Strange rooms conjuring up visions to make your hair stand on end, visions of shriveled-up corpses, mouths agape, left hanging for hundreds of years on the walls to rot, bit by bit. Empty rooms all the same size with light bulbs always left burning so there is no telling day from night.

More important, Kim charged, on the basis of information obtained in prison, that the regime’s case against twenty-two alleged members of a People’s Revolutionary Party (PRP) was a total fabrication. The Rev. George E. Ogle, a methodist missionary, was deported from South Korea on December 14, 1974, because his inquiry into the case, at the request of the prisoners’ wives, showed it to be a KCIA frame-up. James Sinnott, a Catholic priest, was also forced to leave South Korea in April for protesting the PRP case. On March 14 KCIA agents again arrested Kim for violations of the anticommunist law. The authorities charged—quite incoherently, and with no evidence—that his essay had supported a “subversive organization,” the PRP, and had benefited North Korea.

Eight alleged members of the PRP were hanged at dawn on April 9, less than twenty-four hours after the supreme court had upheld their convictions. Under South Korean custom and law the men were entitled to appeal for clemency. But the Park regime, anxious to prevent further revelations and protests about the case, violated these traditional rights and summarily executed the prisoners. Even the US State Department stirred from its normal torpor on human rights matters in South Korea to condemn this act.

After the hangings, the Seoul prosecutor applied Article 9 of the anticommunist law to Kim Chi Ha’s case, ruling that as a second offender he was liable to the death penalty, although Kim has no prior conviction. On May 13, Emergency Decree No. 9 banned all forms of criticism or dissent under penalty of long prison terms.

The South Korean government has launched a vicious propaganda campaign abroad to portray Kim Chi Ha as a communist. The KCIA is distributing to the press in the US an English-language pamphlet entitled “The Case Against Kim Chi Ha.” It purports to contain Kim’s own writings which prove “beyond doubt” that he is “a Communist deeply influenced by the Marxist ideology and strategy.”

According to the pamphlet, “a routine investigation,” described as “a regular practice of any state’s enforcement activities,” uncovered “unexpected new facts” about Kim which showed he violated the anticommunist law. Although the law is supposedly aimed at communist subversion, the government uses it against any dissenters. South Korean authorities told an Amnesty International mission that the following would be considered violations of the law:

1) Publishing an essay arguing that capital punishment is morally indefensible;

2) alleging that the present government in South Korea neglects the rights of the poor and underprivileged;

3) stating publicly that the KCIA uses torture to extract false confessions.

The KCIA pamphlet claims to present the truth about Kim as “admitted freely in his own words and writings.” The Amnesty International mission, however, found that “torture is frequently used by law-enforcement agencies, both in an attempt to extract false confessions and as a tactic of intimidation.” It deemed “political-criminal” trials in South Korea to be “a wretched mockery.”* Methods of torture, according to the report and Kim’s article, include water torture (cold water forced into the nostrils); electrical torture (usually applied to the toes and genitalia); hanging prisoners upside down with ropes (known as “the airplane,” or as “Genghis Khan” if the victim is lowered over a fire); and burning with flames and cigarettes (a prominent political prisoner, So Song, has been hideously disfigured by such means). The medical effects of torture include ruptured eardrums, abscessed lungs, and prolapsed anuses. One must consider in this context the KCIA’s claims that Kim “freely admitted” the charges in this pamphlet.

The KCIA is correct, however, when it says that Kim presents them with “a clear and present danger” (they shamelessly quote the words of Oliver Wendell Holmes). Anyone courageous enough to stand up to the, Park administration and speak out is a threat. Kim Chi Ha is one of the handful of men and women in South Korea who can be called free because, in spite of KCIA harassment, surveillance, torture, and imprisonment, they do not fear death. As Kim said in “Asceticism 1974,”

Nineteen seventy-four was a year of moments of death one after another; for everyone connected with the struggle it was a succession of confrontations with death.

But, as we are in a position to choose death, we can win. Our task lies in developing the asceticism necessary to grasp this mysterious paradox.

In this death cell, in this cage the CIA opened for me to meet with death, I learned of the birth of my first child—a boy.

I went down on my knees God, I have comprehended your will.

At his first trial session on May 19, 1975, Kim Chi Ha repudiated the so-called “confession” and challenged the court on grounds of prejudice. One of the judges was a member of the tribunal that condemned him to death in 1974. The court recently rejected Kim’s challenge. There will be no justice for Kim Chi Ha in any court under the Park regime. Only international protest will save his life. The Park regime charges against Kim are fabricated and ludicrous, but the threat of his execution is unmistakably real.

We urge all concerned persons to write to the Embassy of the Republic of Korea, Washington, DC; to the US State Department; and to their congressional representatives.

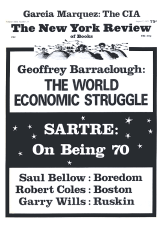

This Issue

August 7, 1975

-

*

Report on an Amnesty International Mission to the Republic of Korea, March 27-April 9, 1975, by Brian Wrobel. This report and an earlier one, Political Repression in South Korea: Report of the Commission to South Korea for Amnesty International, October 1974, by William J. Butler, are available from AI USA, 200 West 72nd Street, New York City 10023 at $.50 each.

↩