Those who are alarmed by New York, as I am, must be alarmed also by John Hollander’s poems, which I register as New York poetry through and through. In the past Hollander has been explicit and defiant about this, as in his witty and accomplished imitation of Juvenal’s third satire, where New York is substituted for Juvenal’s Rome; or in the controlled octosyllabic garrulity of “Upon Apthorp House” (from Movie-Going, 1962), where he thankfully greets the Hudson recovered after years in the New England wilderness:

The wide black river, standing still,

Tilted against my windowsill,

Is still the same phenomenon

I met in nineteen fifty-one

Before I left New York to test

My boundaries by heading west

And, four years later, met at last

The eastern Charles, the Western Past.

Others have a better right than I to protest that Cambridge and New London and New Haven are not much of a wilderness, or very far west; and of course Hollander foresees this protest, and guards against it by writing with this deliberately jokey glibness.

All the same, it remains a characteristic of New York poetry (not just Hollander’s) that it may look north and south, and certainly east across the Atlantic, but very seldom west, into that continental hinterland on which it mostly turns its back. And that eloquently uninterested back turned upon Midwesterners and Westerners can make us—even an adopted and late-come Westerner like myself—not so much alarmed as daunted and irritated. Are we such hicks, so provincially incapable of keeping up with the speed and gloss of the metropolis? Near the end of Tales Told of the Fathers, for instance, there is a series of five poems called “Examples,” each one concerned with a philosopher’s dilemma about language; and a reader like me is divided between shamefaced awe at the thought of a society where particular passages of Descartes, Russell, J. L. Austin, G. E. Moore, and Immanuel Kant are part of the common change of party conversation and a mutinous suspicion that no such society exists, even in Manhattan, and that the whole illusion has been fabricated as a put-down for us country cousins.

The odd thing is that this terrifying knowledgeability in Hollander is something that he has seen, from time to time, not just as a block between himself and his potential public, but as a block between himself and his “best self.” Thus, in “Upon Apthorp House,” when he said goodbye to Harvard and thankfully returned to New York, he regarded it as a goodbye also to one sort of knowledgeability, specifically a literary sort:

Goodbye, Old Tunes! Old modes and feet

Were fine for singing in the street

When all New York was now, and when

Imagined history was then;

When styles one had to find could be

The ultimate morality,

I worked progressions on the lute.

Now I must learn to play the mute.

But knowledgeability or (why fool about?) sheer knowledge is not so easily abandoned or concealed. All Hollander’s later collections have betrayed this, as does Vision and Resonance, the collection of his critical essays that has appeared along with his latest collection of poems.

This is never a good idea, as those of us who are in some sort critic-poets or scholar-poets can mournfully testify; for criticism demands so much less of the reader than poetry that the temptation is all but irresistible for the reviewer to start with the criticism, and deal with the poems as a gloss upon it. If I can do nothing else for John Hollander, I will at least spare him that—I’ll deal with the criticism in short order, in order to get back to the poems.

As a critic, then, Hollander is very learned—and in a field where learning is in short supply, to just the degree that unwarrantedly confident assertion, and by serious characters like Williams, Pound, and Olson, is embarrassingly plentiful; that’s to say, in the area where poetry and music overlap, or seem to. From the twelve carefully interlinked essays that make up Vision and Resonance, one thing that emerges, even for such a musically obtuse reader as me, is the arresting and indeed momentous contention that in English, far more than in French, Italian, or German, the marriage of music with poetry—of chords or notes with verbal sounds—has been, for four centuries and for readily ascertainable reasons, exceptionally difficult; so that a potent notion like “the music of poetry” has been in English for several centuries, without English-speakers recognizing it, a merely metaphorical or figurative expression, as it has not been over the same period for French-speakers, Italian-speakers, German-speakers.

The implications of this are very far-reaching. But it must be said that in his essays Hollander doesn’t always wear his learning lightly. And this is lucky for him; since his writing is so much more sprightly in verse than in prose, at least he is spared the torment reserved for the doubly damned—of having his poems regarded as the spin-off from his criticism.

Advertisement

For those who want to get back to Hollander’s poems, one item in Vision and Resonance is especially interesting: an expansion of his program notes to his own monodrama for music, Philomel (1967-1968). He was working on this in 1962, at which time he recalls that he was

particularly involved in a struggle against wit in my poems, and against talkiness. The former had infected a lot of my contemporaries through the Modernist sanction given to the seventeenth century; the latter was carried to a smaller few by W. H. Auden, and I was trying to emerge from a region of ventriloquism with the ability to articulate something, at least.

My own memories tell me that this was indeed the way it was, for the serious characters among us on either side of the Atlantic, about 1962. And yet it’s just here that the issue of metropolitan-versus-provincial gets in the way once more. For “witty” and “talky” is what Hollander’s verse has remained, long after 1962 and after his return to New York; now, in Tales Told of the Fathers, his poems are still too witty and too talky to be generally liked.

The revealing name in this connection is the one that Hollander gives us: Auden, an adopted New Yorker who, just because he was an adopted outsider, applied himself with exceptional assiduity to articulating a poetic voice for Manhattan. Accordingly those readers who have difficulty with Tales Told of the Fathers—and I can’t readily envisage any who won’t—might usefully read it back to front, at least to the extent of starting, ten pages from the end, with a poem that Hollander addressed to Auden on his sixty-fifth birthday. Hollander’s ventriloquial gifts have never been employed so unerringly, or so gracefully; it is hard to believe that Auden will get another tribute to equal this one. Moreover, with this for keynote, we can turn back to earlier pages and hear harmonies that escaped us at first reading. For instance, not all of Auden was “talky”; and the five poems that Hollander presents specifically as “tales told of the fathers” fall into place with late Auden at his most terse and impassive, as in “The Shield of Achilles”—they are desolate dream images, as that was; and only the last of them fails, by being too witty about a sunset.

In the poem Auden is hailed as Der Dichter; and that’s significant too. For Hollander’s is a profoundly and self-consciously romantic sensibility; and yet he proceeds as if romanticism can not only comprehend elegance, but can feed upon it, be nourished by it—an assumption that we don’t readily take to if we know only Anglo-American late romanticism, with its sloppiness about spontaneity, about “letting it all hang out.” Hollander’s contempt for all that’s merely blurted out, and his determination that his poems on the contrary shall be shapely when they are most desolate and painful, will seem less odd if we remember, with Auden’s name to help us, German romantic music and poetry. Hollander’s romantic Hellenism, for instance, which shows up on several pages here, has more to do with Hölderlin than with John Keats.

As an elegant romantic Hollander has, of course, at least one distinguished American predecessor: Stevens. And Stevens’s idiom—even, sometimes, Stevens’s mannerisms—lie up closer below the surface of Hollander’s style than do even the idioms we might call “Audenesque.” Accordingly readers who have less trouble with Stevens than I have will respond without my querulous hesitations, for instance, to fifteen formally identical poems in a sequence called “The Head of the Bed.” That the inside is the outside, that dreaming is as true as waking, that daybreak and nightfall are therefore interchangeable, that imagination and reality switch places as soon as you think about it—these are propositions to which I give assent under the persuasion of nice diction and cadence, but reluctantly, because they don’t give me what I most hunger for: the fact (or the illusion, if that’s what I must settle for) of some fixed and stable points in the flux of living as I experience it day by day and night by night.

One may say of such a world that in it everything rhymes—inside with outside, night with day, sun with moon; and some people find a comfort in that. Strikingly, Hollander can sympathize with those of us who don’t, as in a poem which celebrates certain words, and by implication the concepts they signify, for which no rhymes can be found, either literally or metaphorically. One such word is “wisdom”:

Advertisement

These solitaries! whether bright or Dim, unconstellated words rain down through the Darkness: after youth has burned out

His tallow truth, and love, which above everything must Cling to word and body, drains, Wisdom remains full, Whole, unrhymable.

This is one of seven elaborately symmetrical stanzas in a poem which names in its title six words, of which “wisdom” is one: “Breadth. Circle. Desert. Monarch. Month. Wisdom. (for which there are no rhymes).” Reading that title, anyone might be forgiven a spasm of irritation at what promises to be only a sterile word game. But this is typical: very often, Hollander’s word games are played for the highest stakes. And so it is here. For Hollander’s romanticism differs from Stevens’s, I think, precisely in aching, in yearning (the corny word is the right one) for a region of nonnegotiable fixities which resist even the cleverest mind’s attempts to turn them into their opposites. And often enough—as in the admirable “Rotation of Crops,” for the moment my favorite Hollander poem—that region has an image for him, one that generations of romanticism have sanctified, as the region of the fixed stars.

But the tales he hears told of his fathers don’t often yield him such assurances. For Hollander, who in the past has been a gay and insouciant writer, is here on page after page experiencing a sort of desolation, at its bleakest in a series of nine poems called “Something About It,” where the central and indeed sole character is one Doctor Bergab. Bergab: gabber. The talkiness that Hollander was struggling to be rid of in 1962 is what enmeshes him still. He can see this as clearly as we can, and most of these poems are preoccupied with just that. Talkiness, mere gab; that’s to say, breath, that’s to say, air. And of the four archaic elements—earth, water, air, and fire—it’s the third dimension, air, whose terrors these poems especially explore, though one of the wittiest of them, “The Ziz,” tells us that the fourth element, fire, is comprehended also. The wit, in any case, is Prince Hamlet’s; deployed to keep terror at bay, it thereby witnesses how real the terror is. And the metaphysical terror is in the possibility that the air we incessantly expel as we incessantly articulate is never bounced back to us off any surface whatever; that there is no being—human or other—that listens, let alone responds:

Doctrinaire of huffa-puffa,

Madman of the emptied shell whose

Creature of meaning dried and died,

He scoops up wind in it, rushing

Out with wordfuls of dead echo

Into the sucking breathlessness,

The wind not pausing to listen.

It is not just “the Poet” who is “doctrinaire of huffa-puffa,” but Everyman.

In Vision and Resonance, at the end of an essay on Ben Jonson, Hollander distinguishes two directions that the modern poet can take “in a world where forms are not given, where style is not canonical”:

One of these is that of American Modernism, following the Emersonian injunction to “mount to Paradise / By the stairway of surprise”—in short, to seize early enough upon a poetic tessitura of one’s own, to frame a mode of singing, as it were, that would make any other formal style impossible. The effect is to dissolve genre: it is not that the poet wishes to make distinguishable, say, “a short, ironic meditation on landscape by Poet X,” but rather only “a Poet X poem.” The other tradition is best exemplified by Auden, and in this he was Ben Jonson’s heir in our age. His grasp of the competing necessities of the public and private realms were mirrored not only in his poetic morals but in his stylistic practice; using a vast array of forms, styles, systems, differentiating between private messages, songs, sermons, inscriptions, pronouncements, and so forth, he made of his technical brilliance more than merely a matter of his own delight. In craft began, for him as well as for his predecessor Jonson, responsibilities.

There is no doubt which direction Hollander has taken. Merely to turn the pages of Tales Told of the Fathers, seeing how—except for certain interlinked sequences—each page presents a new shape to the eye, is to realize that this is a poet for whom the idea of genre is meaningful and precious. Only the idea, of course; for the old system of once canonical genres has been dismantled and will not be put together again. What is held open by Auden or Hollander is the possibility of a different system of genres one day emerging. Hollander might prefer to “genres” the more flexible “modes”—a word that he uses with a musicologist’s unusual exactness. Whichever word we use, we are talking of something important; for discrimination between kinds of stylistic behavior in writing reflects and may even enforce discriminations in other kinds of behavior, and it is surely on discriminations of that kind that rests any idea of civility, of mutual consideration. There may or may not be a Being who listens to the little gouts of air, called words, that we expel toward him; but if there is, the least we can do is to address him not always in the same tone of voice, whether a manic shout or a querulous grumble or a precarious suavity.

And if this is what a New York poet like Auden, or Hollander in his more constricted way, is saying, then the rest of America—at whatever cost to its currently cherished preconceptions—needs to listen.

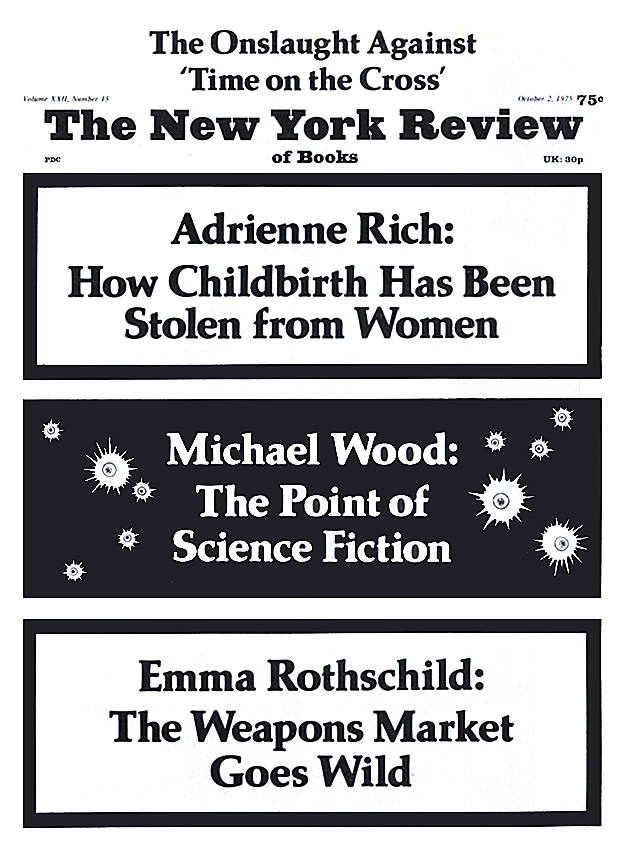

This Issue

October 2, 1975