Ever since Greek tragedy was rediscovered by the West in the early Renaissance, it has been more widely read in translation than in the original. Greek in the modern world has always been an elite accomplishment and the Renaissance editions of Greek tragedy, like many of their modern counterparts, were bilingual—Latin translation on the facing page. What is surprising is that when the time came for English translation, tragedy was so badly served: unlike Homer, it did not attract the poets—it has no interpreter even remotely comparable with Chapman or Pope. Dryden, the translator-general of his age, Englished all of Vergil, much of Lucretius, Ovid, Juvenal, and Persius, some of Horace, Theocritus, and Homer; he versified Boccaccio, modernized Chaucer, and even converted Paradise Lost into an opera “in Heroickal Verse,” but he never laid a finger on Aeschylus, Sophocles, or Euripides.

Shelley translated a play of Euripides but it was the satyr play Cyclops (bowdlerized at that), and Browning produced a sentimental travesty of the Alcestis and a typically eccentric version of the Agamemnon. But these two poet-translators are the exception: for the whole of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the Greekless reader saw Attic tragedy through the distorting spectacles of verse written by scholars whose acute perception of the nuances of ancient Greek was exactly matched by their crass insensitivity to the sound and sense patterns of English. Aeschylus paraded in the rococo trappings of Potter—“But you, my friends, amid these rites / Raise high your solemn warblings…”—or played the reluctant clown in the archaic shreds and patches of Morshead—“I rede ye well, beware!” “Speak now to me his name, this greybeard wise!”

By the early years of this century, those Greekless readers (a condescending Victorian equivalent of “deserving poor”) were no longer an embarrassed minority of the educated; they were now an important intellectual constituency to be won over for the classics. For tragedy this task was undertaken with enthusiasm and success by the Regius Professor at Oxford, Gilbert Murray, a great Hellenist and also a public figure whose impact on the life of his time, like that of Jowett before him, was not confined to Oxford—as Shaw’s affectionate caricature of him in Major Barbara testifies. Murray’s verse translations (of Euripides and Aeschylus) were intended for performance and were in fact extremely successful on stage: they were also accepted by the public at large and some of the critics as English poetry in their own right.

This is a judgment time has rescinded. Murray would occasionally in the choral passages rise to giddy Swinburnian heights (he could also sink to nameless bathetic depths), but for the dramatic dialogue he adopted a form which only Donne could handle successfully—rhymed couplets which are, for the most part, not closed. One can understand his recourse to rhyme as a protest against the lifeless blank verse of his predecessors (“Blanker verse ne’er was blunk,” to quote Walt Kelly) and in this he had the enthusiastic support of Granville Barker (who demanded for Greek tragedy “a formal decorative beauty, scarcely attainable in English without the aid of rhyme”) but, quite apart from the faintly spastic effect of rhymes which usually do not point up and sometimes work against the sense, the insistence on rhyme over hundreds of lines of dramatic dialogue exacts a heavy price in warped syntax, violent inversions, and, above all, fulsome padding. This was the target of one of Eliot’s lethal shots: he pointed out that Medea’s prosaic six (Greek) words—“I am a dead woman, have lost all joy in life”—were transformed by Murray into the rococo jewel, “I dazzle where I stand / The cup of all life shattered in my hand.”

Most of Murray’s translations predate World War I: as Western civilization plunged deeper into its own tragic age, the poets were drawn to Greek tragedy. Yeats made a stage version of Sophocles’ Oedipus (in prose—except for the choruses, which, though magnificent, recall the Liffey more than the Ilissus) and formulated the modern program: “The one thing I kept in mind was that a word unfitted for living speech, out of its natural order or unnecessary to our modern technique, would check emotion and tire attention.” In the next generation MacNeice (so great a poet that few realize he was also a professor of Greek) produced a spare, virile Agamemnon, Pound published (1954) a typically aggressive version of Trachiniae; in America, Fitzgerald turned out a memorable Oedipus at Colonus (1941) and Lattimore began, with a fine Agamemnon, the translations of Aeschylus and Euripides which became standard versions for their time.

Lattimore is of course a joint-editor, with David Grene, of the Complete Greek Tragedies published by Chicago; it contains the surviving Greek tragedies in versions made and commissioned by the editors (eight by Lattimore and five by Arrowsmith)—the earliest done in 1941, the most recent in 1958. Oxford has now begun to issue, under the general editorship of Arrowsmith, a series called The Greek Tragedy in New Translations, which is, presumably, going to translate the whole corpus of thirty-three plays over again.

Advertisement

Apart from the fact that poetic fashions change (more rapidly in the twentieth century than the nineteenth), there are good reasons for going back over the ground. The Chicago translations, though infinitely superior to anything else available in the immediate postwar decades, have their bad spots. Lattimore and Arrowsmith can be depended on to produce English verse that, while it does not always scale the heights of Parnassus, never stumbles into a pratfall, and they are both careful, accurate scholars. But their collaborators are in a different league. There are some real blunders in translation, some of them badly misleading in passages crucial to interpretation; there are passages of grotesque translationese which seem to have come from the hand of Potter’s ghost—“What will befall me? I swoon / Beholding the citizens agèd”; but worse than the occasional outrage is the steady bleat of dramatic verse doggedly penned by professors whose normal medium of self-expression is the footnote.

The aim of the Oxford series is, to quote its general editor, to produce “a re-creation of these plays—as though they had been written, freshly and greatly, by a master fully at home in the English of our own times” (so Fitzgerald in 1941 said of the Oedipus at Colonus: “it can be rendered only in what might be called the English of Sophocles”). Since there are few contemporary poets who know Greek well enough to bring over into their versions what Arrowsmith calls “that crucial otherness of Greek experience…its remoteness from us,” some of the plays are tackled by poet-scholar teams. The first three Aeschylus plays to appear in the series present us with one scholar-poet, Janet Lembke (Suppliants) and two teams: Helen Bacon-Anthony Hecht (Seven Against Thebes) and John Herington-James Scully (Prometheus Bound).

For a translator Aeschylus is of course the most formidable of the three tragedians. Even his own countrymen, in the next generation, blended admiration for his archaic grandeur with amused appreciation of what their more rhetorical taste thought crude and gigantic. The modern translator has to find an English equivalent for a dramatic idiom which, though distant enough from the talk of the street to serve as the language of gods and heroes, still preserved the contemporary resonance essential for popular drama. The problem is of course insoluble for many reasons, one of them the lamentable fact that since the early seventeenth century English has had no poetic drama worth the name, has developed no verse style suitable for the stage and acceptable to a mass audience. The Shakespearian achievement, dramatic poetry which possessed both high solemnity and a contemporary rasp, remains unique—and inimitable. The translator of Aeschylus has no pilot to help him steer a course between the Scylla of archaic silliness and the Charybdis of swiftly obsolescent colloquialism.

These two extremes once assumed for this reviewer a paradigmatic form which suggested a private terminology for judging translations of Greek tragedy. I was collaborating with a gifted actor-director on a prose translation of Sophocles’ Oedipus which was to be used by actors in an educational film. We were in a hurry: working directly from the Greek, I fed him the lines to test for their speakability. I was concerned to be swift, clear, and direct, no matter what other values might be lost, and when we came to the great scene in which Oedipus forces the truth out of the reluctant herdsman, I gave my collaborator the line: “Grab him! Tie his hands behind his back! Quick!” He looked at me malevolently, pulled an imaginary fedora down over his forehead, stuck a real cigar in the corner of his mouth and snarled the line back at me in what passes on the English stage for a Chicago accent. “What is this,” he asked, “a gangster epic?” Challenged to do better, he put down the cigar, waved a hand that transformed the fedora into the likeness of a kingly crown, rose to his full height, and, pointing a menacing finger down at me, bellowed: “Pinion him!”

We eventually compromised on “seize,” but I have ever since thought of the horns of the translator’s dilemma as Pinion and Grab. With Aeschylus the main danger is obviously Pinion: the characteristic blemishes of Aeschylus-in-translation are archaisms (Biblical preferred), complicated inversions, and distressing echoes of the fashionable poetic strains of yesteryear (if not of yestercentury). It is a pleasure to be able to say that the three translations under review are all written, for better or for worse, in twentieth-century English.

Advertisement

Lembke, the only scholar-poet of the three, has the most intractable of the plays. The Suppliants of the title are dark-hued Egyptian daughters (fifty of them) who, led by their father Danaos, seek the protection of the Greek city of Argos against the violent courtship of their fifty cousins, sons of Egyptus. Their claim on Argos is that their great-grandmother Io was a princess of that city before—loved by Zeus but persecuted by his wife Hera—she was transformed into a cow and driven, half-mad, round the eastern Mediterranean to Egypt. In the play the Argive king gives way before their passionate appeals and threats of suicide on the altars; he takes up their cause against their cousins. In the next play of the trilogy (now lost) he was defeated in battle; the Suppliants were forced to marry their cousins, but all of them (except one) cut their husbands’ throats on their wedding night. How the third, final play developed, we do not know; we have only a few lines of it, part of a speech by Aphrodite, which give divine justification to that sexual union the Suppliants so fiercely refused. The motivation of this fanatic hatred of marriage is not clear from the text of the play and the text itself is hideously corrupt (some passages are a mosaic of modern and Byzantine corrections and guesswork). The translator’s difficulties are compounded by the fact that this is of all the Aeschylean plays the most profuse and violent in its imagery.

Lembke has met these multiple challenges magnificently. Image and metaphor are translated with fidelity: “If Aeschylus implies that Zeus’ gaze is a bird, then the gaze is not like bird but is bird.” Greek meters are not reproduced, but replaced by “English…rhythms that seem affective equivalents.” And everywhere the verse moves with the energy and harmony, the language with the precision and opulence, of a poet speaking her own tongue. “But Aphrodite is not scanted here / nor do her rites lack eager celebrants. / …. And she is thanked, guile-dazzling / goddess, for her solemn games. / And in her motherlight soft daughters walk….”

There are of course occasional passages which will send scholars back to the Greek with raised eyebrows. For most of them she supplies a note explaining her interpretation (or reading) and provides a literal translation where she has taken “great liberties in order to make evocative English poetry.” Sometimes the liberties degenerate into license, as, for example, when “land of Argos” becomes “earth cupped in the day’s hand.” It is true that the name of the city is identical (except for accentuation) with an adjective that means (among other things) “bright”—but that cup and hand are pure Pinion. And by a weird coincidence they are the same extraneous objects Eliot shot down from Murray’s high-flying Medea. But such extravagances are rare. For page after page Lembke’s Suppliants creates the illusion that it is written in the English of Aeschylus.

The Seven (another play avoided by most translators) is the work of a team. Helen Bacon is a scholar well known as a sensitive critic of Greek tragic poetry; Anthony Hecht is of course an acknowledged master of his craft. The result of their teamwork is technically dazzling as well as deeply moving. Hecht, unlike Lembke, has used rhyme as the armature of the elaborate choral odes, but rhyme, the despotic master of the versifying professor, is here the vibrant but subtle instrument of a musician. “It is a bitter sight for the housewife / to see, spilled piecemeal from her cherished store, / the foison and wealth of the earth, the harvest riches, / grain, oil, and wine, dashed from their polished jars, / sluicing the filthy ditches. / And by the rule of strife, / the pale, unfamilied girl become the whore / and trophy of her captor….”

The shock effect of “ditches” and “whore” provides an English equivalent for the Greek’s re-creation, in relentlessly formal metrical patterns, of the waste and horror of the city’s fall. Hecht sustains this high level throughout; this is an English poem in its own right. At times, he seems to have left Aeschylus far behind; I can find, for example, little basis in the Greek for the splendid lines: “You were yourselves misfortune’s instruments, / the silenced theme infecting these laments.” And yet, on reflection, one sees what he is doing. Aeschylus, in this passage, was relying for his effect on music, dance, and the psychological tension, familiar to the audience, of the hysterical yet formal wailing over the dead; Hecht has only printed words to work with, so they must work three times as hard.

Translators may not be always traitors but they are, whether they like it or not, interpreters: both of these versions, as their authors candidly state, are new interpretations. Lembke sees the solution of the Suppliants’ motivation—their wild disgust for marriage—in a “refusal to assume adult-hood” which has its roots in the fact that they are “archetypal victims of a father fixation.” The villain of the piece is their father; “the play has a madman, and it is Danaos, author of his daughters’ lives and their…deepening insanity.” Those who know the play in the original will search it in vain for traces of this Egyptian Barrett of Wimpole Street; Danaos is a faceless tritagonist, a dramatic nonentity whose function is to report what happens off stage, a puppet ineffective in action and Polonian in speech. Unfortunately Lembke’s strange vision of Danaos has colored her translation: the very first reference to him—his daughters’ “Danaos, father”—becomes the brilliantly suggestive but quite unjustified “Our father on earth.”

Bacon and Hecht take similar liberties. One example will suffice. It is important for their staging of the central scene (and interpretation of the play) that the six Theban champions should appear on stage and that each one, like his Argive opponent, should have a symbolic blazon on his shield. The text mentions only one (Zeus on the shield of Hyperbios) but our translators assume that the others also carry images of the gods, the seven gods prayed to in the opening choral ode, whose statues are represented on stage. Except that Eteocles, who should have carried the image of Aphrodite, surprises us by revealing on his shield the Fury. This is already complicated and conjectural enough to raise the hackles on the critic’s back but there is worse to come. The chorus in the Greek text prays not to seven but to eight gods: this inconvenient fact is dealt with by the lordly expedient of leaving one of them, Hera, out of the translation. The technical reasons given for this omission in a note will not satisfy most scholars, who will await with interest the defense, promised “elsewhere,” of “such liberties as we may be thought to have taken.”

The third volume, Prometheus Bound, offers no such wayward interpretations: the scholar of the team is a recognized authority on the problems posed by this play and its lost successors (or successor). The illuminating introduction, informative notes, and valuable appendix are a distillation for the general reader, as well as the scholar, of original research and critical evaluation maturing over many years. The translation is, of the three, the closest to the Greek. It is also the least exciting. It is of course true that the language of this play shows so little of the metaphorical exuberance and complexity typical of Aeschylus that (for this and other reasons) many scholars have doubted its Aeschylean provenance—doubts finally laid to rest, in most scholars’ minds, by Herington’s work on the subject.

The style is direct and simple, even in the uncharacteristically short choral odes. Here the demon menacing the translator is not Pinion but Grab, and Scully seems to have had trouble fighting him off. His translation, he says, is “more idiomatic, yet more literal than other versions of the play.” More idiomatic it certainly is: “Clamp this troublemaking bastard to the rock…. MOVE damn it!… OK OK I’m doing my job…. I see this bastard getting what he deserves…. The boss checks everything out…. So be a bleeding heart!… You cocky bastard….” What is this, a gangster epic?

It is true that this colloquial banter occurs mainly (though not exclusively) in the prologue and is an attempt to re-create in contemporary terms the Aeschylean vision of intelligence crucified by brute power. But though Aeschylus assaults the audience’s sensitivity with all the pathos, terror, and savagery of the situation, he does so with language which for all its force never loses dignity. If naked Power itself could speak Greek, Aeschylus persuades us, it would sound like this. Can we believe that if it spoke English it would have to fall back on “bastard” three times in one short scene? Scully also has what seems now (so many years since the Cantos) an old-fashioned fondness for capitals and typographic pranks: what is gained by printing

MAJESTY OF MY MOTHER

and of

SKY SKy Sky sky

—the last line looking like a neon sign with circuits going out of phase? Unlike Hecht, he rarely uses rhyme; one passage in which he does leaves one wishing he hadn’t. “You’re all so young,” says his Prometheus to Hermes, “newly in power, you dream / you live in a tower / too high up for sorrow.” The similar rhythm and length of the two rhymed phrases leads the ear to connect them—and to recognize with dismay that their form is that of the two short lines of the limerick. Edith Hamilton did not claim to be a poet but her version of these remarkable lines is much better: “Young, young, your thrones just won / you think you live in citadels grief cannot reach.” But elsewhere Scully’s translation reads very well, especially in the long Io scenes:

Having crossed the stream between Europe and Asia

—towards that dawnworld where the sun walks, flare-eyed—

you’ll move on over swells of an unsurging sea.

These

are dunes, it’s desert!

And, taken as a whole, it is better than any other Prometheus now in print.

The Oxford series is off to a good start. Murray in his day built a bridge between the Greek text and the modern reader; in less than two decades, Eliot found it “a barrier more impenetrable than the Greek language.” All translations share this fate in the end; in the case of these versions of Aeschylus it can be confidently predicted that they will have many decades to run before they have to be replaced.

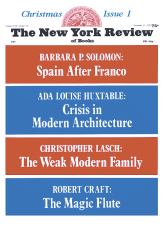

This Issue

November 27, 1975