The Famous Writers’ School, Silly Putty, “Attack of the Puppet People,” empty Schlitz cans, a Pontiac Chieftain, the Conrad Veidt Fan Club, Vogue, Debbie Reynolds, Kierkegaard, John Hawkes, Batman, the New York Times Sunday Magazine—the list is a sampling (one per story) of the ingredients of Donald Barthelme’s first book, Come Back, Dr. Caligari, and in 1964 it was surprising and delightful to find serious literary intentions being pursued with indifference to the distinction between “high” and “popular” culture.

But the radical quality of Barthelme’s early stories was often blunted by the nature of his materials and his audience. If he was writing studies in a dying culture, they were also—like The New Yorker, where most of his work appeared—meant to seem amusing and unthreatening to the creatures of that culture, living or at least imagining cosmopolitan lives while keeping up with the charming vulgarity outside.

Here is a party scene from an early story, “Up, Aloft in the Air”:

A Ray Charles record spun in the gigantic salad bowl. Buck danced the frisson with the painter’s wife Perpetua…. “I am named,” Perpetua said, “after the famous type-face designed by the famous English designer, Eric Gill, in an earlier part of our century.” “Yes,” Buck said calmly, “I know that face.” She told him softly the history of her affair with her husband, Saul Senior. Sensuously, they covered the ground. And then two ruly police gentlemen entered the room, with the guests blanching, and lettuce and romaine and radishes too flying for the exits, which were choked with grass.

The story’s Last-Days-of-Pompeii implications are covered over with Perel-man-like whimsy, and the confrontation between the licentious and the “ruly” seems less a point than an embellishment. The details are the point—Perpetua’s assumption that only the “famous” matters and that history slips away unless you keep it pinned down (“in an earlier part of our century”), Buck’s pun, the wild mixing of people and salad greens triggered by “blanched” and leading to what in 1964 would have been virtually an in-joke about “grass.” The touch is delicate, the play of associations uncannily supple, but the governing mood remains unshakably chic.

That mood was shaken in Unspeakable Practices, Unnatural Acts (1968). These stories consider with surprising directness the pressure of political and social turmoil upon the static, ahistorical world that the culture of affluence represents as life. Barthelme’s collages begin to include strong images of ethnic vengeance (“The Indian Uprising”), crisis politics (“Robert Kennedy Saved From Drowning,” “The President”), the law-and-order mentality (“The Police Band”), the purposeless technology of modern war (“Report,” “Game”). But this overtly political mood moves into more generalized forms of anxiety in City Life (1970), as if Barthelme had answered no to the question he posed in “Kierkegaard Unfair to Schlegel”: “Do you think your irony could be useful in changing the government?”

The first story in Sadness (1972) begins with a man reading the Journal of Sensory Deprivation while his wife Wanda reads Elle, and the book continues the absorption of radical energy into aesthetic or domestic meditation (though Wanda ends up studying Marxist sociology at Nanterre). We find stories about Paul Klee, psychiatry, film-making, the theory of capitalism, St. Anthony, the failure of love and youth. An occasional image of Vietnam, busing, or racial violence intrudes, but these now seem scarcely more menacing than the appearance of King Kong at a party—he turns out to be an adjunct professor of art history at Rutgers who’s as easily subdued by pleasure as anyone else. ” ‘It is hard to make the revolution with a bassoon,’ the bassoon player said” (“Perpetua”), and whether he said it with regret or secret relief, he was of course quite right.

No condemnation is intended here. For all its alertness to realities beyond the media, Unspeakable Practices, Unnatural Acts seems to me (except for Snow White, a tedious countercultural soap opera) Barthelme’s thinnest book, just as Come Back, Dr. Caligari and Sadness, which in their different ways are the least concerned with social and political matters, are probably his best. The terms of Barthelme’s art don’t easily accommodate the most difficult terms of life, and a distant and grave sense of absurdity, not feeling close-up, is what he has to give us.

But even in the subdued moods of his recent work something recalcitrant remains alive. At one point in his new book, The Dead Father, the title character responds to an invitation to be emasculated with a Skilsaw by reasonably remarking, “I would prefer not to,” and in that voice I hear the voice of Barthelme the Scrivener, enclosed in his own intransigent purposes and still saying no. The Dead Father is stripped down—the Skilsaw is one of its very few allusions to the culture of “products” and personalities—and its economy of means seems to suit our recent discovery that material possibilities which used to seem limitless are terribly small after all.

Advertisement

The Dead Father is described by its publishers as “a novel,” and although that’s not quite right, still it is a more connected work of fiction than anything Barthelme has yet written. The connections are admittedly rudimentary: a recurring set of characters with ordinary names like Thomas, Julie, and Emma, who embark on a quest, broad comedy alternating with pathos, intimations of “larger” significances that are decently obscured by some attention to what’s human and social. There is even, in the best eighteenth-century practice, a digressive book-within-a-book as well as continuing exchanges of anecdotes and personal histories. The methods, that is, are ones that Fielding or Dickens would be easy with.

They would have been less easy with the substance of Barthelme’s book. The Dead Father (“dead only in a sense”), in one of his aspects a colossal Gulliverian figure, has always been the reality of his children:

No one can remember when he was not here in our city positioned like a sleeper in troubled sleep, the whole great expanse of him running from the Avenue Pommard to the Boulevard Grist. Overall length, 3,200 cubits. Half buried in the ground, half not. At work ceaselessly night and day through all the hours for the good of all. He controls the hussars. Controls the rise, fall, and flutter of the market. Controls what Thomas is thinking, what Thomas has always thought, what Thomas will ever think, with exceptions. The left leg, entirely mechanical, said to be the administrative center of his operations, working ceaselessly night and day through all the hours for the good of all. In the left leg, in sudden tucks or niches, we find things we need. Facilities for confession, small booths with sliding doors….

He is God, machine technology, civil and economic law, an idea of the world as ordered, equitable, and perhaps benign, an embodiment of collective selfhood and its history like Joyce’s Finn or Blake’s Albion.

He is also, dead or not, the Father, the terrible possessor of the power that was here before we were, the continual reminder of how little power and freedom we can negotiate for ourselves. The book describes a small band of his resentful children leading (or dragging) him—now aboveground, alive and sometimes kicking—toward the Golden Fleece which may, he hopes, rejuvenate him. But it turns out to be another kind of fleecing; after relieving him of his belt buckle, watch fob, sword, passport, and keys, his children reveal the object of the quest, a woman’s public hair which he’s not even allowed to touch, and they make him lie down in an enormous excavation while they bulldoze the earth over him.

Lest this simple parable of contemporary rejection seem unclear, Barthelme gives us sufficient evidence of the Dead Father’s possessiveness and vanity, his instincts for vindictive, murderous violence, and his theatrical self-pity, as well as a childishly written Manual for Sons condoning generational mistrust but taking a prudential view of killing the father:

Patricide is a bad idea, first because it is contrary to law and custom and second because it proves, beyond a doubt, that the father’s every fluted accusation against you was correct: you are a thoroughly bad individual, a patricide!—member of a class of persons universally ill-regarded. It is all right to feel this hot emotion, but not to act upon it. And it is not necessary. It is not necessary to slay your father, time will slay him, that is a virtual certainty. Your true task lies elsewhere.

The manual’s translator (“from the English”) is one Peter Scatterpatter. Because its advice is so convenient to fathers who would prefer not to be killed, and because some of its phrases later turn up in the Dead Father’s own thoughts about dying, we may suspect that the name signifies not scattering pater but pater scattered into other guises, at work ceaselessly for the good of all, and especially of himself. But his sons and daughters throw the book into the fire and go about their anti-authoritarian work.

The idea of “fatherhood as a substructure of the war of all against all” happily doesn’t completely overwhelm the novelist’s playful interest in his characters—the Dead Father can sometimes seem a lovable old rascal or a pathetic figure beset by rather priggish young enemies, and the book is unexpectedly sad, as if much of the fun had gone out of watching centers fail to hold. But they do fail, they are failing all around us, and in reading this new book I was struck by this sophisticated writer’s attaching to conventions of fictional order disintegrative devices that are more suggestive of Beckett than of Perelman. There are long passages of intricately contrapuntal dialogue in which “character” almost, but not quite, disappears into the random retrieval of cultural data, as in this conversation between the book’s two women:

Advertisement

He’s not bad-looking.

Haven’t made up my mind.

You must have studied English.

Take my word for it.

How did that make you feel?

Wasn’t the worst.

I queened it for a while in Yorkshire.

Did you know Lord Raglan?

I knew Lord Raglan.

He’s not bad-looking.

Handsome, clever, rich.

Yorkshire has no queen of its own, I believe.

Correct.

I suppose that Jane Austen (“Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich….”) gets into these idioms of social and phrase-book banality as a reminder of how the family novel began and how gravely it has declined. But such passages, in a book built out of the wreckage of a great literary form, seem to me to convey more affectingly than Barthelme’s earlier, more glossy work the mysterious power of language to perpetuate itself, if nothing else, even with the bleakest material. The Dead Father does not always succeed, but it suggests a hopeful future for a writer whose talent may not yet have found its most hospitable form of expression.

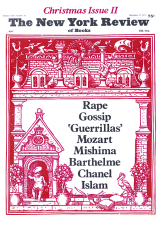

This Issue

December 11, 1975