Early in his memoirs the great Victorian journalist Henri de Blowitz refers to his “uncontrollable desire to get at the bottom of sensational reports.” He was trying to explain why he became a journalist, instead of remaining a sober businessman in Marseilles. This was the best he could do. In a later chapter he discusses what was in “universal opinion, the greatest journalistic feat on record,…the publication, in the Times, of the Treaty of Berlin at the very hour it was being signed in Berlin.” Needless to say, de Blowitz was the person responsible for this triumph. But plainly he felt some puzzlement about exactly why it was such a feat.

To have published an important document before anybody else does not make you a great writer or even a great journalist…. Any journalist by profession might have done what I did if he had said, “I will do it,” and had thought over the ways of accomplishing his scheme. It was a feat in which neither talent nor science stood for anything. The story I am about to tell must not therefore be ascribed to vanity, but should merely be considered as the fulfilment of a duty to my journalistic profession, to which I am devoted.

Evidently de Blowitz could see that detached readers might well have asked what exactly was the point of a feat in which the Times of London managed to print a document on a Saturday only through prodigious efforts and enormous expense, whereas this same document was freely distributed to every journalist in Berlin shortly afterward.

At the heart of de Blowitz’s confusion was his difficulty in confronting the fact that his sense of pleasure and triumph was that of the gossip, the person first with the news, suffused with the satisfaction of having slaked that “uncontrollable desire to get to the bottom of sensational reports.” Such, in essence, was the duty he felt toward his profession.

Now journalism has always been fair game for abuse, and though they may have made a fuss about Spiro Agnew, most members of the profession readily concede the fact. Indeed the more seasoned of these members will invariably commend Evelyn Waugh’s novel Scoop to novices, explaining that this chronicle of mendacity, idleness, venality, and ignorance is a splendidly accurate distillation of their calling.

But “gossip” (or even “mere gossip”) is not one of the terms of abuse genially acknowledged. There are, to be sure, gossip writers enjoyed by the readers. Particularly in England a good gossip page is regarded as a sine qua non of such papers as the Daily Mail or the Daily Express or The Evening Standard. More avowedly serious newspapers such as the London Sunday Times or The Observer acknowledge the need, with gossip columns purged of excessive prurience or outrageous snobbery. These responsible efforts are of course extremely dull. In the United States prurient and snobbish gossip is reserved for the huge mass circulation papers like the National Enquirer and sanitized gossip enjoys a brisk renaissance in Suzy’s syndicated column, or in People magazine or in the ever-expanding column in The New York Times also called “People.”

But although gossip sells papers, the activity of gossip-mongering is still corralled off as an activity with which the “serious” journalist should not concern himself. The reason is surely that gossip-mongering is at the heart of the psychopathology of the trade, at the center of that “uncontrollable desire” de Blowitz was talking about. All journalists worthy of the name are gossips, but many of them find this simple urge, central to their calling, too distasteful to recognize. They often prefer to turn matters around and talk about “the public’s right to know” rather than the journalist’s need to tell. The gossip’s ambition is to discover a secret and the gossip’s triumph is to reveal that secret, whatever treachery in the broaching of the secret may be involved. Back in the nineteenth century John Delane, de Blowitz’s boss as editor of the Times, remarked that the duty of newspapers is to obtain the earliest intelligence of the news and instantly communicate this to the readers. Which is a nicer way of saying the same thing: “I’ve got a secret, and here it is.”

All the same the exact psychopathology of the journalist is hard to figure out. No foundation that I am aware of has hired ex-journalists to promote a thoroughgoing inquiry. Journalists themselves are notoriously repressed about the wellsprings of their conduct, merely recognizing that the occupational hazards of their chosen career include alcoholism and a meager and probably impoverished old age.

The repression may help to explain the commotion over Barney Collier’s little book Hope and Fear in Washington (The Early Seventies): The Story of the Washington Press Corps. The commotion is, to be sure, largely confined to the Washington press corps, but in such quarters it is fierce. And leafing through the book you can see why. Collier, formerly of the Herald Tribune, then of The New York Times, and now a free lance, has produced a work of such evidently cruel triviality that the reader constantly asks himself why on earth a grown man should have felt compelled to write it. The interest in the book lies precisely in this sense of compulsion, the fact that Collier’s intent seems to be to display himself in a gossip’s neurotic dance of death. From inside the book a bad novel about journalism is probably struggling to get out, but Collier cannot manage this, and presents a series of sadomasochistic encounters with some of the well-known journalists in Washington.

Advertisement

After a while the rhythm of the book becomes familiar. He visits, say, Dan Rather, or Rowland Evans, or Eric Sevareid, or James Reston and engages them in meandering conversation. They often ask him what exactly he is writing about. Collier answers vaguely, for he knows—and after a while the reader knows too—that his plan is usually to make them look ridiculous, to trap them into foolish remarks, to reveal some “secret.” The sort of journalism that these people actually put out does not concern him. It is usually enough that they are deemed to be successful. The reader knows after a while, as did surely Collier, that the book does not lead anywhere in the orthodox sense. There are no conclusions, no judgments. The point merely lies in the sadomasochistic exercise, whereby Collier presents himself visibly to the readers as a shit, but at the same time makes it plain that there will be hell to pay when the book is finally published.

The sadism is often rather routinely conveyed. Collier is deliberately discourteous in his description of women. “She has substantial hams and drumsticks” is his phrase for the wife of one journalist who is having him to dinner. Such a physique seems to interest him, because he describes Sally Quinn as having “a heavyset rump held up by thick, sturdy legs.” This is just before a startling burst of sadistic megalomania in which he announces that “I was angry at myself after seeing Sally Quinn for seeing her so harshly, snooping under the phoniness she hid in the medicine chest and the dresser drawers and the old purses of her mind. I had asked her merciless questions, never letting up, although she finally closed up and stopped moving, poor moth, toward the end.”

The masochism takes various forms: references to his ludicrous failure to obtain a job as a television news announcer; repeated mentions of his departure from The New York Times, for reasons which remain cloudy but seem to coagulate around problems over his expense account. Then there is the more covert masochism of his constant indications that he, Collier, finds it humiliating to be harrying all these important journalists for interviews. Above all, the pervasive masochistic pleasure that he is breaking the rules of normal journalistic behavior and will have to meet the eyes of his offended subjects once they have read his book.

Central to the whole project is the frisson of the gossip. Can he find out secrets? Will he dare publish them? Yes, Yes, Yes I will, Yes, he screeches to his readers in a kind of terminal autoerotic frenzy. And he does, for Collier performs the gossip’s ultimate obeisance to his calling, which is to spill the goods on himself.

There’s an amusing moment in his encounter with Sally Quinn where Collier says, “I let her know a few facts about me, as little as possible because I felt nothing I told her was safe from some eventual abuse.” It takes one to know one, as they say—but Collier’s expressed fear struck a bell and I turned to Sally Quinn’s own record of her brief and unpleasant spell of employment at CBS, We’re Going to Make You A Star. Like Collier’s book this is another useful addition to the literature of the psychopathology of journalism. It’s a revenge memoir, in which Miss Quinn, partly disguising her project as a rueful narration of failure, lets the reader know she is getting her own back.

Toward the end of her story Miss Quinn recounts a conversation with her agent Richard Leibner. She has decided to leave CBS and they are discussing the all-important matter of the contract. ” ‘There are an awful lot of people around here who are worried that you’re going to write a book,’ said Richard. ‘I’m sure they’d be much more lenient about letting you out of your contract if they could have some assurance that you weren’t going to write anything.’ ‘Richard,’ I said, ‘fuck ’em.’ ”

Advertisement

She’s telling the truth, as the reader well knows, because already Miss Quinn has narrated in some detail the abortive attempts of a CBS reporter to seduce her in the course of their trip to London to report the wedding of Princess Anne. The reader knows, because Miss Quinn has already told him, that this same producer called her after the London trip. “He wanted to apologize and could we be friends? He didn’t want to read about what happened in England in ‘any fucking book you might write.’ I said we could be friends. That’s all.” There’s the authentic journalistic bash at self-exoneration for you—the virtuous tones of the gossip under imagined assault, the slightly indignant yet satisfied stress that friendship definitely did not exclude a plan to ridicule this producer in print as soon as possible by publication of his secret.

Elsewhere Miss Quinn records her astonishment at a breach of the gossip’s code by the journalist Hunter Thompson. She tells of a brief exchange between herself and her colleague Hughes Rudd, and Thompson who was to appear on their morning show.

“At one point,” writes Miss Quinn, “Hughes gently reminded him that he was here as our guest and we just assumed he understood he was not to write about this experience. ‘Shit,’ said Hunter, looking bewildered. ‘I’ve got to. I’ve already sold this story to a magazine for several thousand dollars.’… ‘Hunter,’ I said, ‘The New York Times wanted to send a reporter and a photographer down here to spend the night with us and we refused. We can’t tell some people no and then let others in.’ ‘Okay,’ said Hunter. ‘I promise.’ I don’t know why, but I believed him. So did Hughes. So far he hasn’t written anything.”

I don’t know why, but I believed him….”—it’s such a charming and revealing phrase, written with all the amazement of a gossip who spends much of her working life persuading people that she is not seeing them with the intent of making them look foolish or persuading them to utter statements that might look ridiculous in print. This, by the way, should not be construed as a specific sneer at Miss Quinn. The great de Blowitz was just as interested in the tricky business of extracting gossip without being explicitly forced into a relationship where publication of the secret would be interpreted as a direct act of treachery and betrayal.

“I am going,” he said, “for the benefit of younger journalists, to give a hint which a good many of them which I know would do well to bear in mind. When a man gives a correspondent an important piece of news, the latter should continue to remain with him for some time, but change the conversation and not leave him until it has turned to something quite insignificant. If the correspondent takes his departure abruptly, a flash of caution will burst upon his informant. He will reflect rapidly and will beg the journalist not to repeat what he has said till he sees him again. The information would be lost, and the correspondent would suffer annoyance that might have been avoided if he had heard nothing. A newspaper has no use for confidential communications it cannot transmit to its readers.”

Only the last sentence of de Blowitz’s admirable advice rings oddly. It is after all plain that newspapers constantly find use for confidential communications they feel they cannot transmit. They sit on them, glorying in the possession of knowledge but deterred by reasons of libel or taste or genuflections to national security from letting the readers in on the secret.

There are other reasons why the gossip-monger’s excited babble is suppressed. The editors or proprietors may simply feel he is wrong. Official censorship may interrupt the confidential communication. This constant tension between primal gossip and eventual publication is the theme of Phillip Knightley’s book on war correspondence, The First Casualty. On the whole it is an interesting, if slightly dogged account of how newspaper reports of almost every conflict since the Crimean war turn out, upon examination, to be unrelievedly mendacious. There are varying patterns of distortion. Either, as was often the case during the Russian Revolution, the journalist’s own powers of observation were so contaminated by class prejudice that he was literally incapable of understanding what was going on around him. Or, as was famously the case in the Spanish-American war, the proprietor simply wanted a war, whether one existed or not. Or, in almost all cases, the military authorities and the civil government back home did not wish to have the population acquainted with perturbing information. Against such alliances of interest, the triumph of truth—as Knightley tells it—has been rare.

The only problem about the book is what exactly Knightley considers “truth” to be. This is most conspicuously evident in his examination of the bombing of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War. Knightley starts with the proposition, originally advanced by George Steer in the London Times, that, in Steer’s words, “The object of the bombardment was seemingly the demoralisation of the civil population and the destruction of the cradle of the Basque race.” Knightley shows how such an interpretation of the bombing became a potent weapon in the hands of propagandists and sympathizers of the Republican cause. Then he quotes supporters of the Nationalists who claim that the bombing of Guernica was a brilliant propaganda coup by the Republicans.

Finally he calls up two authorities, Professor Hugh Thomas and Professor Herbert Southworth, to give their interpretations. He quotes Thomas as saying that “the town was bombed by the Germans…probably not as a shock attack on a specially prized city, but as one on a town where the Republican-Basque forces could regroup….” He quotes Southworth as agreeing that the Germans did the bombing and then as asking “Why was it done? This is more speculative. There is nothing to show that the Germans wanted to test civilian morale. German documents tend to show that it was a tactical operation.”

Knightley now mops up: “So Steer’s original accusations, the birth of the legend of Guernica…now stand contradicted…. Thus it is clear that the correspondents made Guernica. If Steer, and, to a lesser extent, Holme, Monks, and Corman, had not been there to write about it, Guernica would have passed unnoticed, just another incident in a brutal civil war….”

There seem to be several problems with this triumphant conclusion. First, the quotations from Thomas and Southworth seem much more tentative than Knightley’s comment would warrant. Second, Knightley seems to demand some ethereal definition of objectivity and restraint from correspondents like Steer. They would presumably have been allowed by Knightley to report that Guernica had been bombed; that the war factory outside the town had not been attacked, that it was market day and the civilian population had been machine-gunned as it fled to the fields, that the town had been laid open with high explosives and saturated by incendiary bombs.

But there they would had to have stopped, prevented by hindsight from saying that it was a shock attack or that the Germans were trying to test civilian morale. In sum, they should have concluded with the sedate observation that “this is just another incident in a brutal civil war” and, presumably, “a war in which many atrocities have been committed on both sides.” The heart of the matter is that the psychopathology of journalism has no place for untoward ideological enthusiasm, and untoward ideological enthusiasm is exactly what Knightley feels he is sniffing in the Spanish Civil War.*

The true journalistic gossip tells his secret, heedless of the consequences. But Knightley’s book makes it dismally clear how easily this small pure urge to communicate is extinguished, and how easily it is compromised. The My Lai massacre was not exposed by one of the hundreds of journalists who had worked in Vietnam, but by Seymour Hersh, working for a small news service in the United States. Military obstruction may have impeded the efforts of journalists in Vietnam, but it seems dubious that this was the reason why My Lai took so long to be uncovered.

Journalists may start with the pure urge to tell all but their working lives are spent in environments profoundly hostile to this primal desire to tell all. Knightley has chosen the most conspicuous environment—that of war, where it may simply be absolutely impossible for the truth to be communicated. Readers may come away with the comforting illusion that things are better in peacetime. But it does not take too long to see that then too the gossip stands in permanent danger of blunting his edge. Can he truly say what he knows about business, about law enforcement, about government? As a gossip, he has to have sources who can and will deceive him, use him for their own ends, reproach him for indiscretions, cut him off from fresh material.

Social gossip is all very well, because the subjects like to read their names in the newspapers, even attached to vaguely disobliging remarks. What about powerful people who do not wish to see their names printed in the newspapers? The gossip moves about his village, but each day faces the neighbors too. He modifies and inflects his news accordingly. I.F. Stone chose, in compiling his own splendid newsletter, a slightly different method, less amenable to contamination. He did not move along the usual gossip circuits, but preferred rather only to read source material, congressional reports, budgetary statements. And in that way he remained immune from the compromises to which his colleagues almost invariably fell prey. Many of them had inside stories, embargoed, off the record, on “deep background,” too heavy with “advocacy.” They had the wherewithal to satisfy that basic lust to be first out with the secret, but lacked the freedom, or eventually the inclination, or indeed the moral passion, to satisfy it. Such disappointments do not make journalists cynics, as is popularly believed. It makes them despair.

Despair is a central part of the psychopathology, as Collier’s horrible book makes quite clear. For the hand-maiden of gossip is treachery: the record is never off; the tape recorder is always on. Usually the macho of the trade precludes self-awareness, as did the general feeling of journalists that they were a rough, low lot without the leisure for introspection. But journalism seems to be becoming a more respected or rather self-respecting profession. Perhaps more self-analysis is on the way. One hint of this can be found in a book edited by a journalist and his wife, called The First Time, in which a number of prominent people talked about their first sexual experience.

A couple of journalists are in the collection, giving the inside story on their first times—primal gossip again—and I was much struck by the contribution from the columnist Art Buchwald. Toward the end of it he says,

I had hang-ups and guilt that didn’t help. I put women on a pedestal, but fundamentally I was very hostile to them. I was trying to get even with my mother. Trying to get even with your dead mother is one of the most futile drives. There’s no payoff. A lot of revenge fucking of that sort goes on. But I can’t do it. I can’t be cruel. I can have fantasies about being cruel, but I can’t do it. I used to have a lot of rape fantasies, and my being Jewish, they had to do with fucking Wasps, country-club girls, the girls at Palm Beach or the girls at Smith and Vassar. My fantasies were always of making it with the unreachables, and if you’ve got a good imagination, your sexual fantasies are always better than anyone possibly could really be….”

Back we go to Barney Collier who says that Douglas Kiker told him that Buchwald likes him to tell stories of sexual conquest over lunch at Sans Souci. “Art sits enthralled. When Doug pauses in his story, Art is afraid it’s over too soon and goes ‘Yeah? Yeah?’ And Doug, who wrote two long novels, prolongs the climax. ‘Art loves it,’ Doug said. ‘Especially when I get to the fucking part. He keeps saying, Yeah; Yeah; Yeah.’ ”

It’s a quintessentially journalistic passage; one gossip relating the gossip of a second gossip who himself is admitting to gossipping to a third person who is quite prepared to gossip about himself to yet another gossip who is putting together a book about first sexual experiences.

It’s too early for a complete theory of the psychopathology of journalists but I would commend to investigators Heinz Kohut’s essay on narcissism and narcis-sistic rage in Volume 27 of The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child. Kohut talks about the desire among those suffering narcissistic rage to “turn a passive experience into an active one.” Then he reports the case of Mr. P.

Mr P,…who was exceedingly shame-prone and narcissistically vulnerable, was a master of a specific form of social sadism. Although he came from a conservative family, he had become very liberal in his political and social outlook. He was always eager, however, to inform himself about the national and religious background of acquaintances and, avowedly in the spirit of rationality and lack of prejudice, embarrassed them at social gatherings by introducing the topic of their minority status into the conversation.

Although he defended himself against the recognition of the significance of his malicious maneuvers by well-thought-out rationalizations, he became in time aware of the fact that he experienced an erotically tinged excitement at these moments. There was, according to his description, a brief moment of silence in the conversation in which the victim struggled for composure after public attention had been directed to his social handicap….

Mr P’s increasing realization of the true nature of his sadistic attacks through the public exposure of a social defect, and his gradually deepening awareness of his own fear of exposure and ridicule, led to his recall of violent emotions of shame and rage in childhood….

It seems to be as good a definition of a gossip as any I’ve read recently.

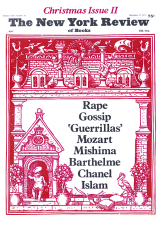

This Issue

December 11, 1975

-

*

For the record it should be added that Knightley says that my father, writing under the name Frank Pitcairn for the Daily Worker, was “unfit to report the Spanish Civil War,” because he believed what he was writing, copy supportive of the Republican cause, to the exclusion of truthful but adverse material, and also that he wanted other people to share his belief. So Knightley calls him a propagandist, a label my father would cordially accept. They have different views of the trade—but in the end it’s Knightley’s quest for the truly “objective” war correspondent that seems to be vain.

↩