Mr. Des Pres has examined with great attention and an eye for what is theoretically interesting accounts by survivors of the concentration camps of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. Under conditions of “extremity”—Auschwitz, Karaganda—ordinary patterns of behavior vanish and are replaced by other patterns that manifest, so Des Pres believes, certain fundamental truths about human nature. Such truths will certainly be of interest to social anthropologists and to psychologists and psychotherapists; even more, they will be of interest—a more than speculative interest—to all men who know themselves to be moral and political animals and wish to think reflectively about their condition.

There were heroes and saints, men of extraordinary courage and of singular purity of heart, in the camps. These did not for the most part survive. Virtues that in a peaceful society blaze out and enchant even those who have chosen mediocrity were in the society of the camps variations that worked against survival. Equally, treachery and greed were useless even when the motive was to propitiate the powers ruling the camps; the SS, to choose the German examples, for about these much more is known, were so saturated with monstrous longings (Republic 571-579) that small vices must have been to them quite undistinguishable; in any case, as so many accounts make plain, there was a discipline among the victims that restrained or punished the today and the thief. What, then, of those who almost in the teeth of possibility survived to be witnesses and spokesmen, small points of light in the darkness of the time?

Des Pres thinks he can pick out certain individual characteristics and certain features of communal life in the camps that made for survival. Of course, none of these could conceivably be sufficient conditions for survival; and even the idea that they were necessary conditions for survival is full of difficulties. The death-dealing regimes resembled natural disasters such as earthquakes and volcanic eruptions: those survive who survive, by, as it were, a grace of Fate. Certainly, in some cases we should be inclined to think we understand how it was possible for such and such a man or woman to have come through. This combination, we should be inclined to say, of physical strength, moral courage, intelligence, brightness of temperament, was in this case a condition without which survival would have been unlikely, but such a combination would never be a protection against the guns and whips of the camp guards.

A psychoanalytical account may give us insight into why a given man abuses his father; but if we generalize the account to the point where any behavior is compatible with the psychoanalytical account—and where it applies to all sons in relation to all fathers—we feel the explanation offered has come to pieces in our hands, though this doesn’t or shouldn’t bring us to doubt the original insight. It is always tempting to establish a microcosm-macrocosm relation, and one that goes both ways, between gross features and particular cases.

I am not sure that Des Pres has always withstood this temptation. He is inclined to go from the testimony of those with whom he is already on general grounds sympathetic (Eugen Kogon in The Theory and Practice of Hell is an example) to rather firm conclusions, and to put aside the testimony of those others (Bettelheim, for instance, in The Informed Heart) he finds unconvincing. But he does recognize the ambiguity of much of the testimony. He cites the case of one writer who describes Maidanek as a world in which “the doomed devour each other”; but the same writer describes generous and self-sacrificing conduct on the part of fellow prisoners. Another writer tells us that in Soviet camps “the conditions under which we had to live aroused the worst instincts in all of us. All trace of human solidarity vanished”; and yet an utter stranger came to the assistance of the writer and saved his life.

What he gathers from the general testimony of the survivors is something like this. There was in many of them a stubborn will to live that didn’t rest upon spiritual considerations, that wasn’t a fruit of the morality the survivor had professed before arrest, but was a quasi-biological response to the infernal (a word precisely the right one) conditions of life in the camps. It is like the persistence of animals and plants under unfavorable conditions. At times Des Pres wants to say that it is a biological and nonrational response, and in a highly speculative final section of his book he wants to identify this will to live with the “will” to live—the quotation marks around “will” are important—of living species other than man. I will say something about such speculations later.

But Des Pres is uneasy about treating the responses, individual and collective, of the men and women in the camps as purely biological, and he often writes in a different way. For example: “In a literal sense…countless, concrete acts of subterfuge constituted the ‘underlife’ of the death camps. By doing what had to be done (disobey) in the only way it could be done (collectively) survivors kept their social being, and therefore their essential humanity, intact.” This is well said. What are we, then, to make of this summarizing statement in his preface?

Advertisement

…the most significant fact about [the survivors’] struggle is that it depended on fixed activities: on forms of social bonding and interchange, on collective resistance, on keeping dignity and moral sense active. That such thoroughly hu-man kinds of behavior were typical in places like Buchenwald and Auschwitz amounts to a revelation reaching to the foundation of what man is. Facts such as these discredit the claims of nihilism and suggest, further, that when men and women must face months and years of death-threat they endure less through cultural than through biological imperatives [my italics].

I find the conclusion here baffling. Obedience to a biological imperative (that there are such imperatives may be a theological premise, one Des Pres certainly doesn’t accept, or “imperative” may here be metaphorical) is neither dignified nor undignified. When the urge, or whatever it is to be called, is less than an imperative, whether to fall in with it or not is a matter of paying heed to such , as dignity and moral sense, concepts that have meaning only within the context of human culture.

Des Pres shows that under the condition of extremity men become cooperative and go in for symbolic acts that demonstrate their solidarity and reinforce it. Sharing and gift-giving—the latter has an almost unbearable pathos where poverty is so great—become a way of life among members of the camp. A little market economy may even grow up, one ironically close to the egalitarian model of a pure market economy, and sustain a shadowy social life and provoke intelligent activity. These descriptions of what must be called civility in a world with a huge barbaric superstructure are the most moving things in the book.

Des Pres makes some slighting and some polemical remarks about such thinkers as Lifton and Bettelheim and all those others who treat the theory of psychoanalysis in its Freudian or its eclectic form as relevant to an understanding of the prisoners’ behavior in the camps. There is no very sustained argument. Some of it is effective: it is a fair point that if a man lives under a regime which makes him foul himself continually with his own excrement, then it is fatuous to point to what he does as evidence for infantile regression. But his argument is that under conditions of extremity “the multiplicity of motive which gives civilized behavior its depth and complexity is lost.”

This doesn’t seem evident. The inhabitants of the Russian and German camps were for the most part civilized people under the rule of barbarians bred by civilization. To believe that extremity peels off all the layers in the case of mature persons seems doctrinaire and is in fact countered by much of the evidence assembled by Des Pres. Whatever may be wrong with the psychoanalytical model of understanding, it can scarcely be that it breaks down because in the camps men no longer went in for symbolization and sublimation. Des Pres himself provides us with examples of symbolic action: the offering of gifts where what the gifts meant quite transcended their value in the camp situation; and the immense importance attached to the act of washing oneself, even where the water was so foul that the purpose could not intelligibly be said to cleanse the body.

It is rather characteristic of the book that, as in the matter of psychoanalysis, hares are started but not chased for long, certainly not caught. It would have been a more satisfactory book had Des Pres stayed with the phenomenon of survival and resisted temptations to make the odd polemical remark and to sketch out wild speculations about the connections between the solidarity of suffering in the camps and the clinging together of lowly plants and bacteria. Certainly, if one is going to take on a thinker so large and important as Bruno Bettelheim one should prepare oneself for a longer and more elaborate argument than Des Pres goes in for. Great importance is attached by Des Pres to his thoughts about the supposed continuity between behavior in the camps and the solidarity of other living species. I therefore feel bound to say something about this and perhaps the best thing to do is to take a longish piece and comment on it.

Advertisement

Human beings need and desire to be part of a larger whole, to join with their fellows and even…to lose the sense of self entirely…. But just as much, men and women yearn for solitude, they struggle fiercely for an existence apart, for an integrity absolutely unbreachable. That is the basis of dignity, of personality, of the egoism which fuels creation and discovery, and finally of the sense of individual “rights.” But throughout the whole of the biosphere a similar duality is evident. From polymers to man, life-forms are perpetually merging, joining, establishing symbiotic and societal modes of relation for mutual benefit. At the same time…individuation becomes more and more pronounced, a species diverges within itself…until successful breeding no longer occurs. Strangest of all is the tendency of individual organisms to reject tissue from any other organism not “recognized” as “self.” This phenomenon…suggests a tendency toward radical selfhood at the very basis of life. On the human level, this activity of keeping whole and inviolate, this constant resistance to the penetration of otherness, is the essence of dignity.

It is perhaps necessary to add to this passage another that brings out Des Pres’s metaphysical views.

Life has no purpose beyond itself; or rather, having arisen by chance in an alien universe, life is its own ground and purpose, and the entire aim of its vast activity is to establish stable systems and endure. [The authority of Jacques Monod’s Chance and Necessity is later appealed to in this connection.]

This is heady stuff. We can find many parallels in the history of thought: Spinoza, on one interpretation; most of all, perhaps, physical and cosmological speculation in the European Middle Ages. The notion that a single pattern runs through all things, that the analogue of human love is the action of the stars as they move in their paths, imitating and desiring the perfection of the First Mover, that the lion is to the beasts what the king is to his subjects, that heavy bodies desire the center and that flame desires the heavens, and that the four humors of man participate in this pattern, that the numerical relations exemplified in the structure of matter are also exemplified in musical harmony and the celestial dance and the well-tempered soul of the just man—these notions are all of them quite natural and, salted with irony, harmless. To remember such notions and to delight in them is a part of the poetry of existence. Lovers looking upon magnetized iron filings may, of course, say: They’re just like us! That is, we find in the world of nature images of, to quote Des Pres, “societal modes of relation.”

But to claim, as Des Pres does, that the relations between bacteria or lichens or whatever are “societal modes of relation for mutual benefit” is just a muddle. The concept of benefit is necessarily connected with language-using societies. It is harmless to call ants and rooks social animals; so they are and they have signaling systems of great complexity. But they don’t have language and they therefore lack the concept of social benefit. It’s even strange to say they lack the concept, as though they might have had it but just don’t. Concept-using here has no application. Any story we tell about the other animals or the loves of the plants or the solidarity of polymers rests upon a tacit understanding that within there are, as it were, homunculi, desiring, willing, regretting, remembering. If we think away the homunculi the desiring, the willing, and the rest fall away too.

Mr. Des Pres may think it harmless to speak of “the entire aim of [the] vast activity” of life, and so in a way it is. But if he wants to protect himself with Jacques Monod’s authority he must stop talking as though it made any sense to speak of the “aim” of life’s “vast activity.” It is true that the language is so saturated with the ideas of purpose and intention that even Monod finds it hard to use the vernacular without contradicting himself. Whether this is just a brute fact about the language and its history or whether in a deep sense language couldn’t be otherwise, these are questions that serve as starting points for serious thinking.

Quite understandably, Des Pres has chosen to think about the survivors, not about those who didn’t make it, and not about those who ruled the camps. These last are human beings, too, though this is a truth we hate and avoid, and perhaps the most puzzling thing about the whole matter of the camps is not that so many people were moderately virtuous and kept their sanity and dignity, but that other people, petty clerks, some of them no doubt good men in private life, probably not even believers in the Nazi or communist mythologies, should have committed such acts of darkness. Des Pres tends to call them “killers” and says that in choosing criminals as their assistants in running the camps they were choosing men like themselves. This doesn’t take us much further. The puzzle remains.

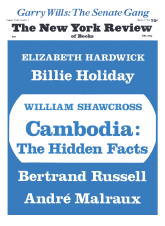

This Issue

March 4, 1976