I

There is a view, quite widely held, that the events of the last two years prove the fortitude of the international financial system. None of the largest banks in the world failed in the economic crisis of 1974-1975; no countries went broke. The neurotic episodes of 1974 and 1975 did not become a psychosis of the entire system, from Nassau and Liechtenstein to Chase Manhattan Plaza.

“The fear is largely behind us,” one prominent American banker sighed in 1975. International banking has come through “this period of uncertainty,” Mr. Richard Debs of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York noted, toward “the emergence of an even healthier and stronger system.”1 This view, or optimists’ position, is not ridiculous. Since 1973, the worst and most widespread international recession since the 1930s has taken place. At the same time, there was the greatest movement of financial resources—from oil importing to oil exporting countries—since the years of reconstruction after World War I. The modern financial order survived these changes without a breakdown comparable to that of the early 1920s and the Depression.

The optimists see further, positive signs of fortitude. “Despite the dire earlier predictions,” Mr. Debs writes, “the system has not only survived but has contributed in a significant way to coping with the problems of ‘recycling’ [oil revenues].” Banks, that is, have borrowed money from oil-exporting countries and loaned it to countries which import oil. Money was recycled through the intermediation of private banks.

David Rockefeller explains the procedure as a question of destiny. “Multinational financial services corporations,” he has written, “were called upon not only to expand their more traditional activities, but also to take on important new responsibilities as well.”2

All the same, one great crisis is still to come. A prospect of unprecedented peril for hundreds of banks and for the system itself, it promises misery and destruction; and with the most profound political consequences.

This is the crisis of the developing countries’ debts. During the 1970s, the developing countries, oil-exporting countries aside, have borrowed more money than in their entire previous history. They now owe some $100 billion to the rest of the world.3 Together, they are spending more than 15 percent of all the money they earn from exports to meet interest and service payments on their external debt.4 By far the fastest increase has been in debt to private banks.

The question for the financial system is not whether these debts will be dishonored. Rather, it is an issue of when, and how, and where. It is certain that at least some of the developing countries’ debts will be rescheduled; that at least some countries will find themselves unable to repay their loans on time, or to meet interest payments. Several countries—Chile and Zaire are notable examples—have renegotiated debt payments in the past year. The new military government of Argentina last month arranged a respite or “roll over” of 120 days on some of its foreign obligations.

The peril to come—the big fear—lies in the conditions of the rescheduling. A debt crisis in one country may lead to further difficulties. One country’s crisis may bring other derelictions: one, two, many Zaires. It may bring the failure of banks, and the breakdown of the system.

The next few months are critical. Even the US Treasury, which takes a resolutely sanguine view of the debt question, sees trouble for several countries later in 1976. Eight countries, according to a recent Treasury study, deserve to be “watched very closely,” including Chile, Peru, Argentina, and Zaire.5 Until the world economy recovers, both the banks and their debtors are in imminent difficulty.

Beyond 1976, there are further problems to come. For the rest of the 1970s, debt reschedulings will be a perpetual chorus in international relations. Several countries will find themselves paying ever more of their earnings as debt “service”—payments of both principal and interest—in 1977 and 1978. The costs of the bank lending boom are only now beginning to come due.

The origins of the debt crisis lie deep in the financial history of the past ten years. The developing countries greatly increased their debt in the recession of 1974 and 1975. This was the recycling process, where banks financed the import of oil, food, manufactured goods. Yet even before 1974, several countries were borrowing unprecedented sums from foreign banks. There was a “good” bank lending boom which preceded the “bad” boom of the recession. For US and foreign banks, the early 1970s were a time of euphoric expansion in Brazil, Peru, the Far East. In the next few years, countries will be paying interest and principal on each set of loans: on both booms.

The debt question will engage the deep political and economic interests of the rich countries, and above all of the United States. Debt is one of the ways in which the developing countries reach out into the banks, the banking system, the national interest of industrialized countries.

Advertisement

Statistics released recently by the Subcommittee on Multinational Corporations of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee provide a view of what is involved for the largest US banks. In Latin America, the twenty-one largest US banks together have made loans now worth more than five billion dollars to Brazil, and another five billion dollars to Mexico; they have claims of more than one billion dollars on borrowers in Argentina and in Peru.6 These figures cover only part of the US banks’ claims, in that they exclude all loans guaranteed by the US government and by US corporations. Yet the banks’ total profit, by contrast, amounted to a little over two billion dollars in 1975.

The involvement of the banks brings political consequences. The relationship between creditor and debtor countries has changed since 1970, and in a way which is as yet scarcely acknowledged. The change goes beyond the increase in borrowing to the new conditions of debt. Ever more of the developing countries’ debt is owed to private banks, as official aid fails to keep up with the growth in the world economy. The distribution of resources is determined, increasingly, by the lottery of private lending, with Brazil or Zaire the big winners. The lasting question for debtor and creditor countries is whether this new order—the new financial basis of development—can be and should be sustained.

These issues are of particular importance for the United States as the largest creditor, with the most claims on developing countries and the most banks at risk. In the next few years, the US government will be confronted again and again with the question of the extent to which it will stand behind its private lenders. Will it assist foreign borrowers, in order to help US banks? The choice will influence US foreign relations. Public munificence would amount to an endorsement, after the fact, of the pattern of lending determined in the bank bonanza of the 1970s; it would mean a further public commitment to Brazil and to the other big borrowers.

There is already an embrace of mutual terror which binds the United States to the creditors of its private lenders. The client countries have a counter-power of their own. Chile is a case in point. The United States was able to wound the Allende government by limiting public and private credit to Chile. Now the US is bound to the Chilean junta not only by political will but also by the loans of American banks. When US officials agreed last year to reschedule Chile’s debts to the US government, they explained that “the choices open to the creditors were either to reschedule or to accept default.” “Cognizant of the unfavorable financial precedent that would be established by default,” they wrote, the creditors therefore agreed to reschedule.7

The change from aid to private lending is part of a quite general change in US policies in the last ten years. In all its involvement with foreign countries, the US has ceded more and more license to private enterprise. The US now earns more dollars from private arms sales than it spends abroad for all military purposes.8 Government-financed exports of food account for an increasingly tiny fraction of all US agricultural exports, amounting in 1975 to less than 15 percent of the value of US farm exports to developing countries; the rest consists of private sales.

As in arms and agriculture, the shift to private bank lending will have consequences for US foreign policy. There will be wars fought with American arms; shortages of food; debt crises. These consequences are nowhere more important, and more unknown, than in the question of debt.

The years since the mid 1960s have been among the great eras of bank expansion: a time of euphoria that can be compared with the bank boom of the 1860s in France and Britain. International lending increased enormously, as banks flourished from Nassau and London to Singapore. The US banks, in their multinational operations, were leaders in the boom.

For most of this century, the foreign business of US banks was leisurely, with Chase Manhattan on the rue Cambon an attraction much like American Express by the Place de l’Opéra As late as 1964, only eleven US banks had overseas branches. By 1974, according to a congressional study, “there [were] 125 banks and 732 branches overseas, and branch assets [had] grown from $6.9 billion in 1964 to $155 billion.”9 Chase Manhattan, now, has branches in twenty-eight countries, with subsidiary banks from Nigeria and Malaysia to Belize.

The new business has been lucrative. In 1975, each of the five largest US banks made more than 40 percent of its profits from foreign operations. Chase was an extreme case. It earned 64 percent of its profits abroad, as compared to only 22 percent in 1970. Its foreign earnings had increased more than 300 percent in the previous five years, while its domestic earnings were lower than they were in 1970. After ten years of boom times, the foreign business of the US banks was vast, and had increased very fast. It was of great importance to the banks’ profits, and thus to the US banking system. It was also free of government controls, at least by the standards of the regulations imposed on US domestic banking.

Advertisement

The banking boom corresponded to real changes in the world economy. In the expansion that began in the 1960s, the US economy grew less fast than the economies of Europe, Japan, and of some developing countries. People borrow money when times are good, and in the world outside the United States times were better for longer than ever before.

Many US multinational corporations increased their foreign investment faster than they increased their domestic spending. The US banks followed their multinational customers to London, Brussels, Brazil.

The boom in overseas lending also corresponded to needs more peculiar to the banking business. For the US banks, foreign expansion has been a way of avoiding the more exigent of US government regulations. Since the banking reforms of 1913 and 1933, US banks have been subject to fairly strict controls in their domestic operations. The Federal Reserve, which has prime responsibility for the banks’ foreign operations, is much less demanding in its supervision of what US banks do abroad, and how they do it.

“It is fair to say,” Richard Debs writes, “that the Federal Reserve’s regulatory philosophy with respect to international banking has been rather liberal, in the sense that it has permitted United States banks to engage in a much broader range of operations overseas than are authorized in the United States…. It has not chosen to impose a restrictive regulatory structure on international banking. I think it is clear that, without this attitude over the years, the remarkable growth of United States’ banks’ operations overseas could not have taken place.”10

The banks’ expansion has been most luxuriant where it is most free of government restrictions: above all, in the Eurocurrency business. Of all the flora of the boom, Eurobanking has been the most fecund.

Euromoney is money held outside the country in whose currency it is denominated. Most Euromoney is denominated in US dollars. Eurodollar banking started to flourish in the early 1960s. The US was exporting dollars, largely through foreign investment and military spending, and foreigners who owned these dollars began to lend and borrow them. An entrepreneur in Germany sells an auto factory to Ford—or a beer to an American soldier—and decides to hold on to the dollars, depositing them in a local bank.

The business grew extravagantly. The Eurodollar market—the total liabilities in dollars of banks outside the United States—was worth around $9 billion in 1964. By 1974 it had grown to a value of some $150 billion. As the market increased, too, US banks themselves began to trade in Eurodollars through their foreign branches and subsidiaries. The US banks now account for well over half of all Eurodollar business.

Eurolending grew faster than the world economy. Much of the banks’ business was done with other banks, as they loaned and reloaned dollars and other foreign currencies. In their domestic business, US banks were required to hold in reserve money equal to a specified proportion of the deposits they accept. There is no comparable restriction on Eurobusiness.

(The Eurocurrency market also includes Euromarks—or marks held outside Germany—Euroyen, and so forth, and it is only loosely a European phenomenon. In the 1960s, most of the borrowing and lending of foreign currencies was done by European banks; and by the European branches of US banks. But any country will do, if its banking regulations are welcoming. “Euro”-business flourishes in the permissive air of small lax nations: not only Luxembourg and the United Kingdom but Nassau, Panama, Singapore as well. Among the more recondite recent deals are, for example, a loan to a Teheran bank provided by the Cayman Islands branch of the Crocker National Bank of San Francisco, three Dutch subsidiaries of Japanese companies, and sixteen other institutions; and an issue of notes by the Ljublianska Banka of Slovenia, Yugoslavia, managed in part by a New York investment firm and denominated in Kuwaiti dinars—Eurodinar finance.)

Eurobanking is by its nature outside the control of national governments. It developed to a great extent because US banks—like German banks as well—were less restricted by their own governments in their foreign operations than they were at home. Its other reason for existing came from the fact that national governments often restricted the export of capital, as when the US in 1965 limited foreign lending by US residents, and therefore by the domestic branches of US banks.

The form of the Euromarket is determined, indeed, by the very restrictions it avoids. It is like a viscous liquid, flowing into the spaces between rules imposed by governments. Thus one official expert on Euromoney concludes that public controls of international capital flows are increasingly “futile.” “Lately the official sector…[has] begun to realise,” he writes, that “the internationalisation of private transactions has progressed to such a degree that some way is almost always found to circumvent these controls or to force further and increasing corrective action to be taken.”11

There is a sort of ontological obscurity which surrounds the Euromarket. Euromoney does not seem to exist in the same way as other money. It seems to be in several places at the same time. It looks illusory: the quickness of the hand deceives the eye, or at least the eye of the solid, temporal “official sector.”

Yet for all this dusk, the growth of Eurobanking was a consequence of certain real changes, both political and economic. One set of changes had to do, simply, with rates of growth, as the US accounted for less of the world’s economy. The US was less important, too, in the world economic order or system. From the mid 1960s, the US government ceded more and more of the responsibilities for international economic policy which it assumed after the Second World War: not to other powers, but to its own corporations.

II

Until 1970, the bank bonanza did not greatly affect the developing countries. Almost all Eurolending, for example, was reserved for multinational companies and for public borrowers in developed countries. Poor countries borrowed vast amounts of money; but most was owed to foreign governments and to international organizations such as the World Bank.

In the economic boom of the early 1970s, the situation changed. Countries like Brazil and Mexico, South Korea and the Philippines seemed lands of opportunity. Foreign bankers flew to São Paulo as though to the new Eldorado. The richer developing countries increased their private borrowing much faster than their official loans. From 1970 to the end of 1973, Latin American countries, for example, increased their debt to private banks more than four times as fast as their official debt.12

The most ecstatic increase came in Eurolending. Developing countries found themselves able to borrow Eurodollars from foreign banks, including the overseas branches of US banks. Brazil was the first large borrower, followed by other Latin American states. By 1972, several African and Asian countries were able to put together Eurocurrency loans. The value of Eurocurrency credits to the non-oil-exporting developing countries was around one billion dollars in 1971. In 1973, twenty-nine of these countries—from Bolivia and Nicaragua to Zaire, Zambia, and Kenya—borrowed almost five billion dollars in Euromoney.13

The lending can be explained, in part, as a consequence of economic changes. There was a delirious feeling to the new credits. People believed in 1973 that the world boom was forever. It was not only bankers who breathed the rare air of perpetually rising expectations. In several developing countries, income and profits increased faster than ever before. For auto corporations and electronics firms, drug manufacturers and engineering companies, the new world of promise lay to the south.

One can see in retrospect how businesses constructed a theoretical justification for their lending and spending. The developing world was classified into categories of promise, each more tempting than the last. One category consisted of “fast growing exporters of manufactures,” which included Brazil, South Korea, the Philippines; all seemed to be serious countries, worth a few hundred millions of Euromoney. There were also “new rich commodity exporters”—countries which profited from the boom in commodity prices of the early 1970s. Peru and Zambia, for example, were counted as promising because they exported copper. Even Zaire, one of the poorest countries in the world, became a cynosure of foreign expectations on the basis of its deposits of copper, cobalt, and manganese.

This theory of hope and riches was self-justifying. For banks, as for other multinational companies, developing countries offered profits which were no longer to be earned in the United States and Western Europe. As in the case of the more general bank boom, the expansion in lending to developing countries corresponded to the banks’ own idiosyncratic needs. Eurobankers, in particular, had quite practical reasons for wishing to see developing countries as suitable clients. There were ever more banks, with ever more money to lend. By 1973, customers in developed countries could not borrow fast enough for the enthusiastic lenders of the Eurocenters. The banks needed to lend money for more than they themselves paid for it, and their well-established customers would pay only a fraction of a percentage point above current interest rates.

It was a “borrower’s paradise” for developing countries, one US investment banker wrote late in 1973: “a growing number of banks, operating free of reserve requirement or other regulations and of the restrictions of a stagnant deposit base, seeking to make foreign loans…[and with] little ability to analyse complex credits.”14

The banks’ ventures—the flora of London and Nassau—were ever more exotic. There are businesses with names like Hypobank International, the Equator Bank, Eurobraz, the International Mexican Bank. Some US banks had regional preferences, with West Coast institutions lending, for example, to Peru and other countries of the Pacific littoral. US and foreign banks founded consortium banks for foreign lending: dividing their risk, but also their sense of bankerly reticence. They lent money in enormous syndicated loans. When sixty-four banks got together to lend $575 million to Indonesia—as they did in August 1975—few looked very closely at Indonesia’s other debts.

The extraordinary expansion of credit is difficult to explain by what are conceived of as conventional banking attitudes. It recalls, rather, J.M. Keynes’s observation of bankers and their view of the international economic situation, written in August 1931: “A ‘sound’ banker, alas! is not one who foresees danger and avoids it, but one who, when he is ruined, is ruined in a conventional and orthodox way along with his fellows, so that no one can really blame him.”

In the years of the bank expansion, the developing countries’ financial situation changed momentously. As private lending increased, official development aid accounted for less and less of the financial flows to developing countries. In 1971, less than 8 percent of the developing countries’ external debt was owed to banks. By 1973, the proportion had risen to 13 percent.

For some countries, the new credit was almost like manna. In 1973 alone, countries were able to borrow more money from private banks than in their entire history. Zaire’s debt to banks grew 300 percent, and Zambia’s more than 600 percent. The credit was extended more easily than official aid. The sorts of political conditions imposed by the US government in its aid programs, or by the official development banks, were of little concern to British or Italian Eurobanks: even to the Eurosubsidiaries of US banks. (Cuba and North Korea, for example, have raised large Eurocurrency loans.)

But the bankers’ largesse was not universal. The more prosperous developing countries did best in the lending lottery. Brazil owes more to foreign banks than all the non-oil-developing countries in Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia together. Two-thirds of all Eurolending to developing countries went to six of the “newly promising” richer countries.

There were no Eurosyndicates for Bangladesh or Burma or Chad. The poorest countries received few commercial loans, and continued to rely on official financing. Since more of the new lending was private, the distribution of wealth was skewed ever more in favor of the richer developing countries.

Even for the lucky borrowers, finally, the new credit was expensive. There were fees to be paid, and interest rates were often higher than on official loans. Most important, the loans were for shorter terms than were available for official debt. The money—the largesse of 1973—was scheduled to come due for repayment in 1975, and every year into the 1980s.

During the 1970s, there has been an unprecedented increase in international liquidity, the assets which are quickly available for use in international transactions. Governments hold international reserves—gold, foreign exchange, the international reserve assets called “Special Drawing Rights” which the International Monetary Fund creates—to protect themselves against balance of payments difficulties, and in rough proportion to their international transactions. These international reserves increased by more than $100 billion between 1970 and 1974. Yet the non-oil-developing countries accounted for only a tiny proportion of this increase. They participated only indirectly in the financial boom: to an increasing extent by borrowing from banks in developed countries.

In this situation of already increasing debt the developing countries approached the current economic crisis. The “good” lending boom came to an end in the spring of 1974. It was followed by a “bad” boom, where countries borrowed money in order to prevent catastrophe, in the worst recession that most developing countries had known.

The recession began soon after the increase in oil prices in the winter of 1973-1974. But it cannot be explained by oil prices alone. The developing countries lost both ways in 1974 and 1975. They paid more for imports of oil, food, manufactured goods, while the, value of their own exports fell. The price of many commodities exported by poor countries—copper, tin, jute—collapsed in 1975. And in the recession the developed countries reduced their imports from developing countries.

Inflation in the price of imported manufactured goods, the UNCTAD studies under review show, contributed about the same to the developing countries’ deficits in 1974 and 1975 as did the increase in oil prices.15 But the developing countries suffered more from the indirect consequences of the oil price increases. The advanced countries exported their adjustment problem of financing higher oil costs to the non-oil-developing countries.

There is a triangle of trade that links developed countries, oil exporting countries, and the other developing countries. In 1974, the developed countries as a group had a large current account deficit. By 1975, they had disposed of this deficit in two main ways. They increased exports of food, arms, and other goods to the oil exporting countries but they also sold more to the other developing countries, and imported less from them.

As Guido Carli, the former governor of the Bank of Italy, said recently, while the “industrialised countries have got back into the black years ahead of schedule…their success has been achieved largely at the expense of the weaker countries in the world.” The non-oil-developing countries actually imported less from the oil exporting countries in the first half of 1975 than they did in the first half of 1974. But their imports from developed countries increased, while their exports fell.16

In 1974 and 1975, the non-oil-developing countries had to find $80 billion to finance their external deficits and to service existing debt. Of this money, some $36 billion was raised privately.17 The international organizations increased their aid, as did the developed countries and the OPEC states. But the greatest increase came in commercial lending.

The developing countries sought every kind of credit. They borrowed from US and foreign banks; from exporting corporations; In Euromarkets. They borrowed long term and short term. The US banks supplied credit from their US headquarters as well as through foreign branches. As the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation reported, “The developing countries as a whole turned to increased short term borrowing and trade financing…. Banks in the United States advanced more than $5 billion in net short term loans to those countries in 1974 compared with $1.5 billion in 1973.”18

Euroborrowing increased during the recession as it had during the boom. The developing countries’ credits were worth $6.7 billion in 1974 and over eight billion dollars in 1975. Brazil alone accounted for more than two billion dollars in new credits in 1975; Peru, Zaire, and Zambia were also able to raise new loans.

The new credit, however, was more expensive than the boomtime loans. The International Finance Corporation found lenders “shortening the maturity of their loans and…increasing the spread of interest rates.” The banks, too, charged increasingly heavy fees for arranging loans. An expert on Eurobanking explained eagerly in 1975 that the periods for which loans were granted to developing countries had shortened “quite dramatically,” while a “very attractive interest rate spread…has opened up this year.”19

As in the boom, the poorest developing countries were excluded from the new, stringent Euromarkets. “This may indicate,” the US Treasury study speculates, “that the poorer countries cannot afford to pay the higher costs of borrowing in this market, or do not represent an acceptable credit risk to the lender.”

But all the borrowers, even the most prosperous, found new difficulties. They were forced to look for more expensive and more uncertain kinds of credit. They found that Eurolenders would suddenly restrict their loans from one month to the next, as the banks were wracked in successive nervous apprehensions. It was not exactly that lenders were following any rational scheme of retrenchment. As the Treasury officials observe, “Even some countries which experienced major problems in 1975, such as Argentina and Chile, were able to obtain significant amounts of additional credit in 1975.” Rather, the process of borrowing became ever more of a gamble.

The only sense to the lending lay in the banks’ own needs. The only scheme was the structure of permissiveness and fear that the banks had built in London, Nassau, the Cayman Islands. Once again, the credit boom can be understood only by examining the requirements of the banking industry itself: as in the expansion of the 1960s, and in the Latin American euphoria of 1970-1973, so also in the abyss of a world recession.

The tempo of lending corresponded quite closely to the moods and exigencies of the banks. Thus in 1975 Eurobankers felt some of the same pressures that they experienced before the recession. In 1974 many developed countries—the United Kingdom above all—had borrowed heavily in Euromarkets in order to finance their own deficits. But the developed countries’ borrowing fell in 1975. In the triangle of trade, the onus of disequilibrium fell on developing countries. As the recession deepened, the banks could find fewer customers in industrialized countries.

By the summer of 1975, therefore, the banks were looking urgently for new borrowers. As Dr. Andrew Brimmer, the former Federal Reserve governor, has said, “While the over-all volume of their resources was registering an even more dramatic rise, these foreign institutions found themselves in an extremely competitive environment characterized by shrinking outlets for their funds.”20 The problem was particularly acute in 1975, he observed, for the British and Nassau branches of US banks.

The banks managed to increase their loans to the poorer oil-exporting countries, mainly Indonesia and Algeria, and to Eastern European countries. But the main chance, once again, was in the other developing countries.

In their lending, the banks observed a curious undulating movement. Thus in the summer of 1974, apprehensive after the German Herstatt Bank collapsed in June, they reduced their loans. As one Dutch banker recalled, “A feeling for the correct proportions and the solidity of banking business gained ground.” But by late 1975, the same banker observed a new boom in lending to developing countries. “Against the background of intensive competition, however, a certain guilelessness gained ground….”21 By the autumn of 1975, Zambia and Bolivia, Peru and Lebanon were again Euroborrowers.

In December 1975, one of the doyens of Eurobusiness looked bleakly at the events of the year. “The industrialized countries of the world now seem to be living in a climate of euphoria,” he said, in that “our banking system has been able to handle the [petrodollar] recycling problem even for the requirements of the less developed countries.” But this achievement was made easy, he said, by the decline in demand for loans in developed countries, and “by the desire of the banks to increase their international exposure [i.e., their lending] in order to secure, and possibly increase, their foreign earnings which they badly need to face the music back home.” 22 “This is an enormous exposure of the private financial system,” he concluded, “to countries that may not be able to service such an ever-increasing foreign debt burden.” Ahead, he saw the possibility of “catastrophic repercussions.”

The waves of lending and trembling continue into 1976. In the winter, after Zaire defaulted on the interest payments for earlier Euroloans, the banks for a while restrained their credits. But this spring, once more, the lending has started over. Recent issues of The Wall Street Journal reveal the old familiar tunes. Thirty million dollars for Bolivia; $300 million for Fiat’s Brazilian subsidiary; $100 million for the Kingdom of Thailand. And the same old singers. Chase Asia Ltd; Bank of Montreal, Singapore Branch; Hypobank International SA; Wells Fargo Bank, Nassau Branch.

I asked a New York investment banker, fresh from signing a new Euroloan to Latin America, why he thought the Eurobankers were returning with the swallows to the finance of developing countries. He allowed that fees were high on recent loans. But basic financial conditions had not changed since the winter, he said, when bankers from London to the Cayman Islands were so apprehensive. Nothing was particularly different. “I think,” he said, “that they just got bored with the subject.”

III

In order to believe in the health of the financial system, the optimists in the US banks have denied certain apprehensions, certain monstrous fears, about foreign lending; about the distribution of reserves; about the “adjustment process” by which rich countries shifted the burden of higher oil prices onto the poor. All these fears come together in the question of the developing countries’ debt.

In the debt crises to come the consequences of these hidden processes will become evident. In some as yet unknown way, the monsters will be released, in the next months or the next years.

In 1976, the developing countries will again need to finance a deficit in their current accounts of over $30 billion, according to US Treasury estimates. This is less than last year, but still more than three times as great as in 1973. At the same time, they need to find ever more money to pay interest and principal on earlier debt.

As the economies of the developed countries improve, the developing countries should be able to export more. Yet their debt problem will remain. Even the US Treasury officials sound apprehensive. “The recent increase in foreign indebtedness,” they write, “will tax countries’ export earnings more heavily in future years than has been the case in the past. This is particularly true for those countries which have borrowed heavily on commercial terms. Thus several countries may have to make adjustments to cope with accelerating debt service burdens in the next 3-5 years.” The structure of these countries’ debt, that is, is such that “service” payments of interest and principal on old and new loans will increase sharply between now and 1980: a dangerous confluence.

One criterion illustrates the peril. It is a banking truism that countries face troubles when they must use a high proportion of their export earnings as debt service. G.A. Costanzo of Citibank, for example, notes (in the same speech, given early in 1975, where he pronounced that “the fear is largely behind us”) that “as a point of reference, bankers usually feel comfortable with country risk exposure as long as debt service as a percentage of total exchange earnings does not exceed 15 to 20 percent.”

As early as 1973, three out of the five largest borrowers of Eurocredits in the developing countries were within or above and beyond this zone of bankerly discomfort. But as export earnings fell in the recession, more and more countries were in peril. By now, on rough estimates, seven out of the ten developing countries with the largest debts to banks pay more than 15 percent of their export earnings to service foreign debts. For all the non-oil-developing countries taken together, UNCTAD studies estimate that the rate will rise from 11 percent in 1974 to 18 percent in 1976 and 21 percent in 1977.23 It is certain, therefore, that some—possibly most—developing countries will try to delay their debt service payments in the years ahead. But beyond this, very little is sure.

If they cannot get delays, countries may default on their payments of interest and principal; they may abandon the debts of one particular public borrower, such as a national oil company; they might act alone or in consultation with their creditors. No country has ever gone bankrupt; no one knows what would happen if one did.

No one is certain, either, about which countries are most in danger. The US Treasury’s group of eight “vulnerable” countries consists of some of the larger borrowers: Argentina, Peru, Chile, Bolivia, Uruguay, Zaire, Zambia, and the Philippines. All were among the countries which three years ago were seen as the “new rich” of commodity exporting countries, and all have suffered a sharp reduction in the value of their exports. Most were large borrowers in both the boom and the recession phases of the Eurocredit market.

The largest US banks, according to the Senate Multinationals Subcommittee’s statistics, have well over $3.2 billion in loans to these countries. Of the loans, $2.1 billion are for terms of less than one year, and come due in 1976.24

Peru’s situation shows the sorts of perils to come for these countries. In 1976, Peruvian borrowers are expected to find $574 million to repay their short-term loans from US banks. Peru’s deficit on current account was over one billion dollars in 1975, and will be slightly higher this year. In the last three years it has borrowed over $1.3 billion in Eurocurrency credits alone. Throughout the 1970s, it spent on average more than 20 percent of its export earnings on debt service.25

Peru, like Chile, Zaire, and Zambia, depends on copper exports for a major part of its foreign exchange earnings. When the price of copper collapsed in 1974-75, its earnings fell quite suddenly. Peru also has the misfortune to import food, and its agricultural imports from the US alone increased from a value of $92 million in the 1973 fiscal year to $200 million in 1975. Its final misfortune was to borrow heavily for its national oil corporation, in a prospecting boom that found almost no oil.

This year and for the rest of the 1970s, Peru is scheduled to pay interest on these recent private loans. Its prospects rest on the most tenuous of hopes, and in particular on the recent moderate recovery in the price of copper, a recovery which has as much to do with the fall of the British pound, and the desire of British investors to hold commodities, as with the resilience of the copper economy.

The Treasury study also expresses concern for a second group of countries—consisting of Brazil, Mexico, and South Korea—which “warrants continued attention since they have large private debts and any debt management problem could have an adverse effect on private capital markets.” The large US banks’ “exposure” to these countries amounts to almost $13 billion in loans, of which some $7 billion are due in 1976.

Many more countries are candidates for crisis. Several very poor countries—India, Pakistan, Ghana—expect increasing difficulties in servicing their debt. Most of the debt is owed to governments and official agencies. Yet default on a World Bank loan, for example, would have some of the same repercussions for the financial system as would default on commercial debt. Egypt, too, urgently needs to reschedule its debt, a large part of which is owed to the Soviet Union.

Algeria and Indonesia, among the poorer oil-exporting countries, also face difficulty in paying interest on foreign debt. The two countries raised more than three billion dollars in Eurocredits in the last three years; the debts of the Indonesian state oil company alone are now estimated at nine billion dollars.

For any of these developing countries, a debt crisis would bring great misery. The process of adjustment to insolvency usually requires a cut in economic growth. Sometimes imports must be cut in a matter of weeks, as foreign exporters interrupt all credit. And many developing countries import goods which are literally necessary to life. Thus most of the eight countries on the Treasury’s “watch” list import large amounts of food. They are not among the most destitute of developing countries. Yet even in a rich developing country such as Chile, the poor have suffered greatly increased malnutrition in the course of a foreign exchange crisis.

The last uncertainty in the debt situation has to do with the consequences of a crisis for the international banks themselves. Just two years ago, the collapse of the German Herstatt Bank terrified the banking world from London to the Cayman Islands. Many bankers still fear that a crisis or series of crises in developing countries could have similar repercussions.

Mr. Pierre-Paul Schweitzer has suggested the extent of these fears. As head of the International Monetary Fund in the 1960s and early 1970s. Mr. Schweitzer presided over the great expansion in international lending; he is now chairman of the Bank of America International in Luxembourg. “I think one has to do something for the less developed countries,” Mr. Schweitzer declared in a recently published interview.26 His language was dramatic. He believes that the situation will improve “eventually”: “That is why I feel so strongly that, in the meantime, anything should be done to avoid disaster.” He was asked, “What you are saying is that no country should, if at all possible, be forced into default?” Schweitzer answered momentously, “I think that default should be avoided at all costs.”

Officials of the Federal Reserve Bank comment reassuringly in a note to the Senate Multinationals Subcommittee that most US lending to developing countries is concentrated at the largest banks. They write that “although large in absolute terms, when compared to the total resources of the six largest banks, the claims data for the selected developing countries appear more moderate. Claims on Mexico and Brazil were each about one-and-one-half percent of the total assets of the six largest banks….” Even when a country’s debts are rescheduled, they add, only a small fraction of bank claims on that country are affected, and end up as “actual loan losses.”27

Yet the extent of bankers’ fears cannot be measured in assets and dollars. Confidence—the health and strength of the system—is of concern to more than the six largest banks.

Several American banks have special relationships with certain developing countries. Thus the Wells Fargo Bank of San Francisco has been since the beginning of the Euroboom a preeminent lender to Peru. Certain US banks with problems at home—the Marine Midland Bank of Buffalo, which is now operating at a loss—are also heavily committed abroad.

A debt crisis in one country, moreover, might affect other borrowers. If a country were to suffer a well-publicized default, banks might react by cutting their lending to many other developing countries. Given the extent to which many countries’ prospects for the next year or so require continuing commercial borrowing, this new stringency could itself bring new crises. Country X defaults and Country Y finds itself guilty by proximity. A debt crisis in Peru would cloud the eyes of foreign lenders as they scrutinize Bolivia; a cut in credit could bring Bolivia to a crisis of its own. This sort of retrenchment is perhaps even more likely, and more perilous, than the actual collapse of banks. Something like it happened in Euromarkets in the summer of 1974 after the Herstatt Bank failed. Several developing countries then found they could only raise money short term and at very high costs.

Beyond these economic repercussions there lies the unknown territory of the politics of debt. The unspoken fear is that a default by one country would encourage other countries to follow suit. Country Y is made bold by the example of Country X. Peru declares that it will no longer pay interest on certain debts, and Panama does the same.

The usual argument against the likelihood of this “imitation effect” is that a delinquent country would find itself, in the words of the Federal Reserve officials, “preclude[d]…from future access to international capital markets.” The most fearsome possibility for the financial system is that countries contemplating default might see safety in multiplicity. They might believe that several countries could not at the same time be excluded from future borrowing; that together, they have nothing to lose but their liabilities.

In the debt crises of the next months and years, these fears will return like monsters. They’ are ‘ fears to which many bankers have closed their minds; to which governments also close their minds, as they cede ever more responsibilities to private banks.

The second part of this article will look at new schemes of public and private lending. It will consider the questions for US policy in the debt reschedulings to come. Even in the past two years, the US government has made decisions of political consequence as it participated in other countries’ crises; as it considered Zaire’s default on certain interest payments; as it chose among Chile, India, and South Korean grain corporations in rescheduling US agencies’ own loans. The questions suggested by these decisions should not be hidden in private business, and in private fears.

(This is the first part of a two-part article.)

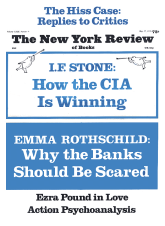

This Issue

May 27, 1976

-

1

G.A. Costanzo, Vice Chairman of Citicorp, January 27, 1975; Richard A. Debs, Monthly Review of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, June, 1975.

↩ -

2

“Report from Management,” The Chase Manhattan Corporation Annual Report, 1974.

↩ -

3

This figure covers only those external debts which are guaranteed publicly in the borrowing country. It also covers only debts for terms of more than one year. Private and short-term debts might add another $30 billion to the total figure.

↩ -

4

UNCTAD IV International Financial Cooperation for Development, supporting paper, TD/188/Supp 1.

↩ -

5

US Treasury, “Report on Developing Countries’ External Debt and Debt Relief Provided by the United States,” January 1976.

↩ -

6

United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Subcommittee on Multinational Corporations, March 11, 1976.

↩ -

7

Quoted in the US Treasury study, op.cit., p. 88.

↩ -

8

Economic Report of the President, January 1976. “US Balance of Payments,” p. 274.

↩ -

9

US House of Representatives, Committee on Banking, Currency and Housing. “Financial Institutions and the National Economy, Discussion Principles.” November, 1975.

↩ -

10

Richard A. Debs, op. cit.

↩ -

11

Eisuke Sakakibara, “The Eurocurrency Market in Perspective,” Finance and Development (an IMF/World Bank publication), September 1975.

↩ -

12

World Bank Annual Report 1975.

↩ -

13

“Publicised Eurocurrency Credits to Developing Countries,” UNCTAD IV, op.cit., Addendum.

↩ -

14

Richard S. Weinert, “Eurodollar Lending to Developing Countries,” Columbia Journal of World Business, Winter 1973.

↩ -

15

UNCTAD IV, op. cit.

↩ -

16

In the first half of 1974, the developed countries had an export surplus of six billion dollars with non-oil-developing countries, and a deficit of $41 billion with oil-exporting countries. By the first half of 1975, their surplus of $21 billion with the first group matched a deficit of $21 billion with the second group. United Nations, Monthly Bulletin of Statistics. “World Exports,” December 1975.

↩ -

17

This is the estimate of the Morgan Guaranty Trust Company’s World Financial Markets, January 1976.

↩ -

18

International Finance Corporation, 1975 Annual Report.

↩ -

19

Pierre Latour, Euromoney, October 1975.

↩ -

20

Testimony before the Subcommittee on Financial Institutions, House Banking Committee, December 5; 1975.

↩ -

21

Dr. M. vanden Adel, Euromoney, March 1975

↩ -

22

Minos A. Zombanakis, Managing Director, First Boston (Europe) Ltd., December 11, 1975.

↩ -

23

UNCTAD IV, op. cit., p. 37. These figures are based on expected earnings from the export of goods alone, as distinct from total exchange earnings; the rates based on total earnings would be slightly lower.

↩ -

24

The Senate statistics cover “selected” countries, not including Chile and Bolivia.

↩ -

25

Peru did reschedule its foreign debts in 1968 and 1969, and closely avoided doing so again early in the 1970s. In the words of an UNCTAD study, the danger “was averted [only] when it became possible to obtain substantial volumes of credit from the Eurocurrency markets .” November 19, 1974. TD/B/C.3/AC.8/9.

↩ -

26

Pierre-Paul Schweitzer, Euromoney, March 1976.

↩ -

27

Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, March 11, 1976, op. cit.

↩