In response to:

Sylvia Plath's Apotheosis from the June 24, 1976 issue

To the Editors:

It was flattering to note that Karl Miller chose a line from a poem of mine as an illustration of the “new barbarism” (NYR, June 24). Perhaps that entitles me to make a comment about the old barbarism with which Mr. Miller seems more comfortable.

To present, out of context and unattributed (introduced simply as coming from “a woman’s poem”), a single line of verse as representative of the same kind of activity as verbal attacks directed at Ted Hughes in public places is to commit just the sort of intentional blurring of distinctions one would have thought Miller was eager to discount in his discussion of Sylvia Plath’s “apotheosis.”

Such displays do not serve to clarify or demystify the mythology which has grown around the life and career of Plath since her death.

For the record I would like to state that neither I, my poem “Ten Years Cold,” written to honor the tenth anniversary of Plath’s suicide, nor the line Miller singled out (“Hughes has one more gassed out life on his mind”) endorsed barbarisms of any kind. On the contrary, that such distortions have interfered with the integrity of Plath’s life, work, and yes her death, was a thematic concern of the poem.

Books such as the three Miller “with misgivings” has written about indeed may be relevant to our knowledge and understanding of Sylvia Plath, the person and the poet. But until all the uncensored, uncut facts become available, partial and fragmentary truths will continue to be discussed and feed the needs of all interested parties.

Mary Folliet

Paris, France

Karl Miller replies:

First, let me explain why I was reluctant to write this article. I had agreed to review one Sylvia Plath book: then there were three, affording a subject matter which had already generated a fair amount of ill feeling, and was bound on this occasion to produce, as it has produced, abusive letters and phone calls. And there was a further reason why I felt reluctant. I did not want to be drawn by the act of reviewing into discussing difficult and painful personal matters which concerned the living as well as the dead. I was conscious, in writing the review, that the feelings of the living should as far as possible be spared and respected, and was keen that those of Sylvia’s mother should be brought into consideration. Thinking the thing over now, I recognize that on one matter treated in the Butscher biography I would have done better to keep silent. Not that I had much to say about it.

Olwyn Hughes loathes Butscher’s book, and in loathing it she misrepresents my view. But a point-by-point rebuttal may not be needed by those readers who recall that one of the main themes of the review was the defects of Mr. Butscher’s approach, with its uncritical reliance on the testimony of friends and acquaintances. His current sneers bear witness to the presence of that theme. Miss Hughes’s letter may or may not cause distrust of his lavish use of gossip, but it certainly shows that any biographer of Sylvia Plath will have trouble gathering evidence, and it makes richly intelligible Lois Ames’s reported failure to complete her authorized life, and to answer letters.

Miss Hughes omits to specify what she objects to in the review, or else exaggerates what is wrong with statements to which she takes exception. She says that, “in guise of indignation on my brother’s behalf,” I quote a line “seemingly” from a wild Women’s Lib poem. There is no “seemingly” about it: the poem exists, and attacks have been made on her brother from this point of view. Because of what was said here, and perhaps also because I later disagreed with him on matters of critical interpretation, she claims I am covertly hostile to Ted Hughes. For many years, as she is aware, I have admired and, when I could, published his work, and I’m sure that this article would not suggest to the uninvolved that I have changed my mind either about his work or about him.

She thinks I am bad because I did not communicate how bad Butscher’s book is. Butscher reviles me for disparaging his book. The two screams would seem to go some way toward eliminating each other, but they concur in suggesting that I have been influenced by Mr. Butscher’s opinions. I hope not, given the state of these opinions, and having had quite long enough to work out my own, on this subject. His letter, which alleges that I take my opinions from him but that they are nevertheless valueless, is comical in its anxiety to give offence, and grim by virtue of its unfeeling complacency. A former Cambridge University teacher is spoken of as a “fine scholar” with “the kind of cool female perceptiveness once celebrated by Agatha Christie.” This fine, cool scholar is on record in his book as detecting little more in Ted Hughes than an uncouth, unlettered provincial, unfit for polite society. The “plackets” passage in the book, which Mr. Butscher mentions, indicates that his devotion to belittling gossip is such that he is willing to copy it out even when his transcription doesn’t make sense.

I was interested to read Mary Folliet’s letter. I am satisfied that the line does not misrepresent what is said in the poem as a whole, and that the poem incorporates what could well be classed as a verbal attack on Ted Hughes in a public place.

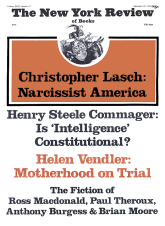

This Issue

September 30, 1976