What has characterized the situation in Poland over the past year is not so much the country’s grave economic crisis as the increasingly clearer manifestations of the resistance of society against the arbitrary behavior of the authorities. Having arisen and developed from different roots, this resistance is gradually taking on the forms of a genuine opposition movement.

For a period of time which began in December 1975, thousands of people put their names to petitions against proposed amendments to the Polish constitution, whose purpose had been to give formal and binding recognition to one-party rule and to Poland’s dependence on the Soviet Union. The force of these protests forced the authorities to make part concessions: the proposed amendments were either toned down or abandoned altogether.

In June 1976 a wave of workers’ strikes, demonstrations, and riots broke out when an attempt was made to impose a drastic increase in food prices without, in effect, any prior consultation. It was a reaction of anger and desperation, caused not just by the considerable drop in real wages—particularly for those in the lower income bracket—but also by the blatant lies of the official propaganda apparatus which once again demonstrated the contempt with which those in power treat the opinion of society at large.

Although on the next day after their announcement, the increases were withdrawn in a panic, those two days in June sufficed to bring into the open the inability of the authorities to solve crucial economic and social problems. In a situation where all groups and strata of society—the workers, the intelligentsia, the peasants, the Church—not only have no political or professional representation, but are not even given an opportunity to voice their aspirations and demands, normal channels of communication, dialogue, negotiation and settlement cease to exist: it has repeatedly been shown that the authorities give way only to direct, desperate action. Such a situation is fraught with dangers. Lack of freedom, economic inefficiency, manipulation of culture and lack of national independence are all intensely felt in Poland, and this has given rise to a state of crisis which could result in an uncontrolled explosion, and this—if it occurs—may in turn bring about a Soviet invasion.

It is a cause for particular concern in view of this state of affairs that instead of digging down to the roots of the crisis and establishing a more favorable basis for its solution, the authorities have responded to the spontaneous protest of the workers with increased repression: thousands of people have been dismissed from their jobs and deprived of means of existence; long-term prison sentences have been passed on participants of strikes and demonstrations; the police have tortured and cruelly beaten hundreds of people—not sporadically, but in organized form, and not during riots, but in the course of investigation.

In September of this year a Committee for the Defense of the Workers was formed in Warsaw. It consists of twenty people, including well-known writers, lawyers, scientists, and also young intellectuals and students. The Committee, with whose aims and means we express our full and unreserved solidarity, is not a political group; its purpose is to give material aid to those who have been victimized and dismissed from work, to inform society about the reprisals, and to counteract the lies of official propaganda on this subject. One of the actions of the Committee, which is of course unable to publicize anything officially, has been to present a motion to the Sejm, or Polish Parliament, that a Members’ commission be set up to investigate and make publicly known the circumstances surrounding the June events and the ensuing reprisals.

The members of the Committee are continually subjected to police harassment; several were arrested, albeit for a short period. In order to cause confusion, the police twice circulated false communiqués, purporting to be from the Committee. In November 889 workers of the Ursus plant near Warsaw submitted a letter to the authorities, demanding the reinstatement of those dismissed for their participation in the strike. Sixty-seven workers from Radom made a written statement concerning torture and beatings by the police. The authorities’ response is once again one of terror and intimidation; in particular, the police are using threats to try and force the workers to withdraw their complaints.

Despite harassment and intimidation, the opposition movement in Poland is gaining strength. It has embraced workers, students, intellectuals, and priests. The Roman Catholic Church in Poland has made frequent statements of late in defense of civil rights, and has protested against the reprisals; its role in mobilizing public opinion has been a considerable one. The increasing scope of the opposition has repudiated official assertions that the strikes and riots were initiated by handfuls of hooligans, and the movement in the defense of the workers by isolated cliques of “revisionists” or adherents of “bourgeois ideologies.” What is more, the development of organized and open forms of opposition may become an important factor in preventing extreme manifestations of spontaneous desperation. There is no doubt that the Party leadership’s credit with society has now run out; its statements and summonses do not arouse confidence, and obedience is becoming more and more enforced. It is our opinion that an explosive situation may arise if methods of negotiating and attaining compromises between the authorities and society are not evolved and implemented. However, a sine qua non for setting such a mechanism in motion is for the various groups—workers, peasants, the intelligentsia—to be able to delegate, by diverse means, their own genuine representatives, who enjoy the trust of their communities and are able to take up an independent stance.

Advertisement

Public opinion in democratic countries, particularly within workers’ organizations, can perform a great role in helping the Polish workers, and less directly in ending or at least lessening the state of crisis, whose consequences could turn out to be grievous not just for Poland. The Polish workers are demanding only a fraction of those rights which go without saying in Britain and other Western European countries. Poland’s intellectuals are demanding only a fraction of the liberties that here are so intrinsic a part of the life of society that no one bothers to even consider them. The Church demands full tolerance of religious practice, which is one of the most fundamental human rights. At the same time the overwhelming majority of Poles share the distinct awareness that the authoritarian rule has been thrust on them, and therefore in Poland resistance against despotism and a striving for national sovereignty are one and the same cause.

On behalf of our friends in Poland who, in conditions of constant personal danger, are openly standing up for civil rights, democratic liberties and national independence, we wish to thank all who have given their support in this struggle. We appeal for yet greater support, both in the form of financial aid for the victimized workers and their families, and in the form of moral and political backing.

AN APPEAL FOR POLISH WORKERS

Once again Polish workers paid with their blood and liberty for daring to come out in defense of their rights.

In June 1976 a drastic increase in food prices was announced by the government without any prior public discussion. In response to this outrage mass protests by the workers broke out in several Polish cities.

The government backed down on price increases under pressure, but at the same time applied immediately brutal police repressions to those involved in the protests. Hundreds of workers were savagely beaten up and arrested, thousands were expelled from their jobs and blacklisted. At least seventy-eight workers have been sentenced to terms of up to ten years in prison.

Under pressure from public opinion and from the Church, some of them have by now been released, but thousands who lost their jobs remain deprived of their livelihood. They desperately need moral support and financial aid.

A Committee for the Defense of Workers (with the participation of Professor Edward Lipinski) has been established in Warsaw to give practical help to the persecuted workers and their families.

We urge you to express your solidarity by contributing to this cause and by adding your voice to the growing volume of the international protests.

Daniel Bell, USA

Wlodzimierz Brus, Poland (UK)

Robert Conquest, UK

Pierre Daix, France

Pierre Emmanuel, France

Gustaw Herling-Grudzinski, Italy

Leszek Kolakowski, Poland (UK)

Edward Lipinski, Poland

Mary McCarthy, USA

Golo Mann, Germany

Czeslaw Milosz, USA

Iris Murdoch, UK

Joan V. Robinson, UK

Denis de Rougemont, Switzerland

Laurent Schwartz, France

Ignazio Silone, France

Piotr Slonimski, France

Alfred Tarski, USA

All donations to be sent to:

IRVING TRUST COMPANY

36-38 Cornhill, London EC3

ENGLAND

Account No: 80-1829

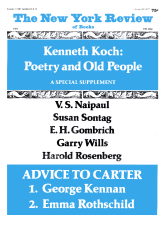

This Issue

January 20, 1977