In one of his collection of Picked-Up Pieces, John Updike suggests that the old novel depended on the old morality which praised God and forbade sexual intercourse outside marriage. Then, when the prohibition of “free-ranging sex” began to fail, the old intricate and heavy plots suffered a sympathetic impotence. His new novel, Marry Me, might appear to have been designed to take account of such developments: lightly plotted, a tale rather than a novel, it is acted out by a cast of middle-class loose-livers. The adulterers of Greenwood, Connecticut, include Jerry and Sally, who are also “exaggerators,” and their respective partners in marriage, Ruth and Richard, who are more level-headed and more truthful.

Marry Me does not declare that a new morality has come. Jerry declares: “Maybe our trouble is that we live in the twilight of the old morality, and there’s just enough to torment us, and not enough to hold us in.” Religion is widely thought, in Western societies, to have waned, and is thought by Mr. Updike to have been succeeded by sex, “as the emergent religion, as the only thing left.” But Updike’s Jerry excites himself with references to God’s grace, and regards Richard as one of the few professed atheists he has met during his “thirty years in materialist America.”

Marriage hasn’t waned either, so far as Greenwood is concerned. However much they may hop from perch to perch, the free-rangers are reluctant to fly the matrimonial coop: Jerry considers that “mistresses are for European novels,” and would agree with his author that “any romance that does not end in marriage fails.” By the same token, any novel that calls itself “a romance,” as this one does on the title page, should, perhaps, end in marriage. In fact, Marry Me leaves it uncertain whether Jerry and Sally get married—and does so in the manner of a particular kind of new novel, where uncertainties are courted and readers are asked to participate in the author’s decisions. Whether or not it should be called a new novel, as opposed to an old, I do not know. Perhaps it is a twilight work in which plot, like marriage, is still there—in an attenuated condition, and at times tormenting.

The novel is published at a time when exaggerators are saying that an Evangelical revival is taking place, and when the rise to prominence of Jimmy Carter has earned respect for the activities of the born-again Christian. The president elect may well believe in the existence of God’s elect, and he has confessed to looking on a number of women with lust. Seen from Europe, Carter is a little like an Updike character, and Updike a little like the prophet of a generation which ranges free and refers to grace. But the novel won’t be received by such people as scriptural, if only because Jerry, the church-going adulterer, will be read by many of them as a pious fraud—what, in the days of the old Evangelicals, used to be known as a whited sepulchre.

Citizens of Jack Kennedy’s America, Jerry Conant and Sally Mathias are in the habit of making love in a fold of the dunes along the coast from Greenwood. He speaks a language that is roguish and voguish—hipster-courtly. He invites her to listen to a “neat record” on the car radio, and addresses her as “my poor brave lady.” It is as if he lacks words of his own, and it is soon apparent that his vamped-up speech is especially dependent on the words of Christianity: perhaps these, too, are someone else’s words, since they do not always describe his intentions, to the extent that we are able to guess what they are. Jerry’s intentions are to do with leaving Ruth and the children in a neat and edifying fashion, and settling down with Sally, who is no poor brave lady but a shallow self-seeker. There in the dunes—Greenwood’s greenwood, so to speak—Jerry thinks the world of Sally. He is later to explain to her that “Richard and Ruth weren’t giving us much. Why should we die just to keep their lives smooth? Quench not the spirit, didn’t St. Paul say?” Imagine what St. Paul would have said in his Epistle to the Inhabitants of Greenwood. But Jerry trusts in Heaven.

During a stolen interlude in Washington, Sally speaks a sentence that might caption some sophisticated ad for daiquiris or deodorants: “If you can’t take me as a wife, don’t spoil me as a mistress.” Jerry, an artist-executive in a high-minded advertising agency, replies with his piece about mistresses being for European novels, and proceeds to a sermon:

“What we have is love. But love must become fruitful, or it loses itself. I don’t mean having babies—God, we’ve all had too many of those—I mean just being relaxed, and right, and, you know, with a blessing. Does ‘blessing’ seem silly to you?”

“Can’t we give each other the blessing?”

“No. For some reason it must come from above.”

Trying to be right and relaxed is made no easier by the difficulty they have flying back from Washington in time to escape detection by their spouses. The airport delays, very skillfully conveyed, are felt not only to threaten Jerry’s marriage but to resemble the forces which detain him in that marriage.

Advertisement

Ruth had previously lain, for a fairly bleak while, in the arms of Richard. The novel now traces their reactions to the news that Jerry and Sally are at it too, but accompanied by an altogether grander music, the music that breaks homes. Jerry, though, can’t decide whether to set up house with Isolde, and it is clear that Ruth is more important to him than anyone else is. In the ever-growing literature of separation, the deserted wife or husband is seldom disparaged, and Ruth is the best person in Greenwood. She has a hard time of it as Jerry dithers. She has to confide in her assassin, as Updike puts it. But their sex “greatly improves,” and one night, with his wife on top of him, the believer experiences something like the Ascension of Christ.

According to the more probable of the novel’s alternative endings, Jerry travels to a romantic Caribbean seaside place, complete with church: “The existence of this place satisfied him that there was a dimension in which he did go, as was right, at that party, or the next, and stand, timid and exultant, above the downcast eyes of her gracious, sorrowing face, and say to Sally, Marry me.” As before, Jerry is talking about doing or being right, which usually seems to mean, for him, being relaxed and getting his own way. These last words of the novel, however, communicate a sense of strain: the sentence is framed as if to refute itself, like a riddle or a puzzle, and you are left wondering whether the “dimension” in which their relationship is to be secured should be identified with that famous place, Heaven. Much of the bravura writing in the book brings the same sense of strain. Uncertainty, interpretability, make heavy weather.

Whether Sally is to cease to be Jerry’s mistress by losing him or by marrying him is the main uncertainty in the book. Another uncertainty is the character of Jerry, in relation to which the reader may once again be expected to assert himself and choose among competing possibilities. Jerry rages and swears at meals because a squalling kid can’t tell the difference between a grace and a prayer, and it is all the fault of his pagan wife. When his wife reckons she may be pregnant by him, he is offended at the thought of an abortion: “It would be no present to me to kill my child so when I die I’ll have this fish in Limbo staring at me.” We are to suppose that this is one of his exaggerations, and he then croons: “Sweetie, you’re going to have a little baby!” These speeches persuade you that the novel is out to punish what Jerry represents, and to reprove this verbal Christianity of his, in which conscience survives as a form of repartee, in which duty is relaxing in bed with a new woman. And yet it may be that a very different response to Jerry is in mind. Asked, on one occasion, if he was religious, Mr. Updike replied that he “tried to be”—which is a version of the answer no. Well, it may be that Jerry represents success, the answer yes, in the manner of the justified sinner or whiskey priest. I hope not.

“Ruth disliked, religiously, the satisfaction he took in being divided, confirming thereby the split between body and soul that alone can save men from extinction. It was all too religious, phantasmal.” This is not the first time that the adverb “religiously” has been placed under strain in New England. There is a sentence in The Blithedale Romance that runs: “She had kept, as I religiously believe, her virgin reserve and sanctity of soul throughout it all.” Does Hawthorne agree with his unctuous narrator here? Does Updike sympathize with Ruth’s dislike, or with Jerry’s satisfaction? The possibility that Jerry is felt to be justified in behaving in this way is quite strong, but a degree of uncertainty remains, for he has, after all, been presented as an exaggerator and as a worshiper of his own satisfactions. Uncertainties of one kind or another are common in Marry Me. Some of them may be deliberate—a deference to the new morality and novel. Others might be taken to indicate that, on the evidence of his latest book, a very talented novelist is currently at sea.

Advertisement

But this is not the only evidence as to what or where he is. No sooner had I shut the novel than The New Yorker published a further story about separation by Updike. His writing echoes to the sound of an unemphatic motherly voice telling some man that he can’t be trusted. That man talks to his wife about her house, and about his sweet-heart: “Her furnace isn’t working very well either.” If this is “domestic life in America,” as the title of the new story proposes, then among America’s leading emotions is that of loyalty to an abandoned wife. The emotion is treated in his novel, and it is the making of his story, which has very fine scenes. It is all the better for having scarcely any of the liberated sexual intercourse with which his later fiction has been religiously supplied, and for having no religion whatever.

Torch Song is a confessional novel about a woman’s first love who turns, in more ways than one, into an abandoned husband. Marjorie Weiss is made captive by her feeling for a gifted young writer and philosopher, a loitering bel homme sans merci by the name of Jim Morrison, and finds herself ministering to his abnormal sexual habits. In the New York of the Fifties, bohemian college students are drinking and thinking deep in the White Horse Tavern on Hudson Street, where Dylan Thomas was once seen plain. Marjorie’s parents are Park Avenue rich, and Jewish. Her mother is a sad, card-playing slut, who lies in bed, dyed, depilated, and massaged, with a glass of whiskey and “a romantic novel of the gothic variety.” Her father is an ill-natured dude lawyer. She drops out by taking up with Jim: she wants to be with him at no matter what price, or rather, she badly wants to pay the price. Morrison is Brooklyn poor, a dandy who thinks of himself as an aristocratic changeling, “the illegitimate child of an English lord or of exiled Russian nobility.” Jim is a romantic person of the Gothic variety, that’s to say, who might almost belong to one of her mother’s novels.

The price Marjorie pays involves enlistment in the drama of his talent, a drama which moves from a dark night of rejection slips to the enthrallingly disagreeable high noon of a succès d’estime, and which is also the drama of his sexual peculiarities.

Sure of me now, he took his pencil-thin penis out of his pants. “Pretend,” he said to me, “pretend for me that you are being screwed in the behind by a large bear. Make the noises, make the motion. Pretend for me. It would make me happy.” I recognized that I had slipped away from the shore and was now in the pirate ship—an outlaw, a social outcast, a demon had possessed me. A dybbuk took over my larynx and I uttered the unutterable sounds he had requested.

Jim is an outcast who has become an outlaw. He is a waif or stray who is also a cross between Lords Byron and Russell, and who can impersonate the Prince of Darkness. This is the multiple identity displayed in certain Gothic novels, where poverty is raised to the peerage and misery consoled, where the forsaken is forgiven his outrages. The Marjorie who affects to be screwed by a bear has already been screwed by the wolf of her boyfriend’s romantic antinomianism.

Jim, whose father earned his living by playing “Mairzy doats” on bar pianos, would “give anything” to be Thomas Mann, and he urges her to read Mann’s story Tonio Kröger in order to discover what she means to him. Tonio Kröger, who is both an artist and a bourgeois, is fancied by an earnest girl who doesn’t attract him, and who falls down at a dance: and Marjorie performs that same action when she and Jim first meet. Her brother Irwin, who drops out into Judaism, bears the same name as a boring boy in Mann’s story. Both works are concerned with the price paid for art: the artist is excluded from normal life and from normal sexuality. Tonio resembles a modern artist when he states that he must keep his feelings separate from his art, and produces an art that is dry, painful, fastidious. There are whispers of Eliot in the tale: Eliot’s essays require the exclusion of biography from art, and the mention by Mann of spring’s cruel effect upon the feelings, and of going south, might seem to anticipate The Waste Land’s opening passage.

At the same time, Tonio is like a romantic artist, and like Jim Morrison, in being an outcast, with secrets. There’s a romantic morbidity—of a kind that might possibly be taken to anticipate one of the moods of Nazi Germany—in Tonio’s final confession of love for blond, blue-eyed, normal Nordic life: this love is described as wholesome and redemptive, a tonic for the sick, sensual artist, but it is also described as a secret soft spot, such as men might have for the normal Nordic male. Tonio is confident that these feelings will pass into his art—exempt from theoretical challenge, presumably—and will transform it.

In Torch Song, as in Tonio Kröger, normality triumphs. Marjorie has a child by Jim, who is not, however, philoprogenitive, and has not been induced by marriage to curtail his absences after nightfall, during which, sprucely dressed, he has done terrible things to prostitutes and has gained the affections of high born blonde girls. The relationship breaks up, and the book ends by the sea, as does Mann’s story, in a jolly, healthy atmosphere of children, fishing, and suntans, with Marjorie married happily ever after to a kind, potent pediatrician. As for her former life with the patrician Jim, it is compared to a shell on the beach, and consigned to the gulls: “I’m done with it.” The narrator is sarcastic about Jim’s subsequent career: “perhaps he gets alimony” from his society wives, “the reviews of his books have not all been good.” Normality’s revenge.

With its accounts of Jim’s strange habits and of a worthy woman’s subjection to these, this book is bound to do business. It is written with a good deal of journalistic force, moreover, and holds in check any tendency it may have to serve as a fresh installment of women’s complaints, of the sort publishers like. But its conception of normality seems very unappealing. “We were married in a legal sense but not in the real sense—the kind that makes babies,” Marjorie points out. Not everyone will believe that the only real unions are the kind that makes babies. An impulse to belittle and burlesque the narrator’s relations with Jim is yielded to, though it is also resisted, and reading parts of the book is like witnessing a punishment more severe than any inflicted on Jerry Conant. Marjorie was very interested in Jim, and stayed with him voluntarily for years, tending his wounds. She needed him, and his price. And now she is interesting readers with her confessions, which would be a lot less interesting if Jim, beneath the brilliance, were unreal—no more than a nursable nasty wreck. Even readers who are repelled by his snobbery and contempt may be unwilling to believe the book when it maintains that this was a relationship for the birds.

All three of these novels are about first loves that come to grief, and about the impediments and separations that lovers have to deal with. Philip Larkin’s, published in 1947, is very much a work that precedes the outbreak of “free-ranging sex”—an event to which a recent poem of his, “Annus Mirabilis,” has had the cheek to assign a date:

Sexual intercourse began

In nineteen sixty-three

(Which was rather late for me)—

Between the end of the Chatterley

ban

And the Beatles’ first LP.

Updike once remarked that his novel Couples has to do with “the change in sexual deportment” which followed the publication of Lady Chatterley: but Larkin’s poem does not permit you to believe, unreservedly, that such a change occurred. Here as elsewhere, he is a poet of constraints, of ironies and sad truths, of the recognition that each person’s life turns out to be “what something hidden from us chose.” Betjeman has called him a poet of “common experience”: normality’s poet knows what can’t be helped, and that “most things are never meant.” For Larkin, who did not admire Lady Chatterley anyway, the sexual revolution would never have been likely to go according to plan, or to live up to its name.

I can remember a time when this writer, who is one of the great lyric poets of the English language, was sneered at in England as a lower-class savage, and a later time when the “gentility” principle lit upon by the critic A. Alvarez was used to insult his achievement. That principle, with its preference for a further and more exotic variety of savage poet, still colors the awareness of Larkin’s work among Americans, and it is doubtful whether the availability in America of the two novels he wrote in the Forties, Jill and A Girl in Winter, will put that right. Only his poems, properly read, will do so. Journals, including The New York Review of Books, have said that the novels, written before his powers as a poet had made his reputation, are proof that his powers as a novelist are not inferior. It is more appropriate to say that these are experiments in fiction, by a poet. Or even that paragraphs, episodes, effects, read like experiments in the type of verse he went on to write: like rehearals, of the kind that poets’ notebooks often incorporate.

There are lines from a much later poem which are like a recollection of A Girl in Winter:

Lost lanes of Queen Anne’s lace,

And that high-builded cloud

Moving at summer’s pace.

In the novel, a girl undergoes a time of crisis, in winter, during the Second World War, and the narrative encloses an account of the same girl in summer, some years before. The summer in question shares with other summers in Larkin the capacity to accommodate a most poignant nostalgia. It is as if they were all the one season, standing for the England of the poet’s childhood, or the gleaming, slow-paced August which unfolded on the eve of the Great War: “never such innocence again.”

Katherine Lind is foreign, vaguely European, come to spend three weeks in Oxfordshire with a pen-friend, the trim, decorous, inscrutable Robin. Sweet Thames runs softly near the house. Tennis is played, punts steered, cucumber sandwiches eaten. The smell, by moonlight, of stocks and wallflowers is enough to make you dizzy. She is drawn to Robin, but nothing decisive happens, and his sister Jane, an intelligent English shrew, is the member of the family who most impresses her. The enclosing narrative shows her back in England, working as a librarian in a shabby Northern town and deciding to renew her acquaintance with Robin. Not that there is much to renew.

The novel insists on the English ordinariness of everything, and the early events, in particular, are told in a manner which is almost disconcertingly grave and low-key. The library is bossed by a curmudgeon of lavish proportions: extraordinary as he is, the probabilities are not breached. Katherine, having quarrelled with him, quits the library to escort a plain, aching girl to the dentist. It is a comment on the traditions of British dentistry that, simply by concentrating on what you could count on finding in such a room, and avoiding all exaggeration, Larkin can turn the removal of a tooth into a scene from a Gothic torture chamber.

The novel suggests that the ordinary can be surprising, and that it can be valuable. When Katherine opened the invitation to go to England as Robin’s guest, “she felt as if she had been holding a live hand-grenade without knowing what it was. It was unbelievable.” In Katherine’s eyes, Miss Parbury “looked ordinary.” But Larkin’s description allows Miss Parbury to blossom and expand. “Rather tall, with a rosy complexion and fair hair, she looked like a large tea-rose gone well to seed.” She becomes as much of a swelling Dickensian grotesque as the head librarian, her disgusting suitor. Presently she’s revealed as a poor brave lady who can teach Katherine a lesson in how to bear things.

At one point, Katherine sees Robin and Jane as “two unremarkable young English people.” English normality is tested throughout against the reactions of a foreigner. Katherine comes across as decent and bright: her ability to pry into someone else’s letter, and her inability to decipher it (“accustomed to grasping any passage at once, she was baulked”), may be offered as limitations or lapses. But she does not come across as foreign. Mr. Larkin used to be known for his aversion to “abroad,” and this portrait of a European might be thought to commemorate a firm refusal to budge from his native shores. A Girl in Winter is bent on deciphering the unremarkably English, and it is entitled to exploit Katherine’s failures as an observer, as well as her successes: but these failures are her only foreign trait.

Eventually, after confusions and delays, Robin calls on her in her Northern town. He is in the Army: his feathers have lost their sheen, and there is something empty about him, and about his pleading to stay the night. She lets him. “She named a condition that he accepted,” but we are not told what it was: this must rank as one of the quaintest and least professional omissions in literature, even if we remember that writers were still reticent then, and that the ban on Lady Chatterley had yet to be lifted. Whatever species of sexual intercourse happens in that bed, the experience will leave her untouched, except in the sense that it may enable her to control, or cancel, what he’d been to her. As they fall asleep, dreams move like ice floes, at winter’s pace, through a darkness that will never be relieved. “Yet their passage was not saddening,” and it was possible to be glad that “such order, such destiny, existed.”

An enigmatic ending, but one which works well dramatically. It is also like a little extra poem: an ode to normality, in which its conditions and impediments are peacefully accepted, or to fortitude—at all events, a very suitable poem for the “Austerity” Britain of the late Forties. Meanwhile, ahead, in the fullness of time, lay the Year of Jubilo, of oral sex and the rest of it—glorious 1963.

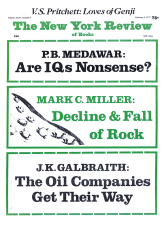

This Issue

February 3, 1977