The fat new volume of Auden’s Collected Poems, superbly edited by Edward Mendelson (and hideously produced by the publisher), gives us extraordinary opportunities to notice the persistence of the poet’s themes and devices. Even in the dark, portentous poems of Auden’s early career, there were clear designs, the language of common speech, and an unpremeditated, dramatic manner. It was, in fact, the balance of these elements against the enigma that drew us in.

If the poems sounded at times like riddles, if the syntax was often knotty, yet the words remained natural and the meaning seemed important. Though we might be unsure of his sense, the author was evidently speaking straight to us, and on timely, even urgent matters. He seemed to assume that we understood, that we belonged to his tribe; and as we groped to trace the way, we felt we were just not sharp enough to follow him.

The latest ferrule now has tapped the curb,

And the night’s tiny noises everywhere

Beat vivid on the owl’s developed ear,

Vague on the watchman’s, and in wards disturb

The nervous counting sheep.

(1933, in the periodical New Verse)

This is the opening of a sonnet about the poet’s missing his beloved. But how much more it seemed to imply!

When the meaning of such poems emerged, it often dealt with the separation or opposition of mysterious persons or groups; with a distinction between two psychic conditions and the yearning for a change from one to the other; with movements between vague regions that seemed oddly cut off and yet neighboring. Slowly, we realized that change of place meant change of condition, that the outer landscape reflected inner moods, and the transformations desired were moral or emotional.

In Auden’s best work the blend of openness with reserve, of well-defined form and riddling tone, of lucid and yet veiled speech, makes in general two subtle impressions: either that valuable truths are being conveyed, or that a distinguished person is showing us, his fellow tribesmen, a self he hides from strangers:

I see it often since you’ve been away:

The island, the veranda, and the fruit;

The tiny steamer breaking from the bay

The literary mornings with its hoots;

Our ugly comic servant; and then you,

Lovely and willing every afternoon.

So begins another poem, of the same vintage, reduced in a later version to a little song (Collected Poems, p. 60). How discreet or perhaps evasive the revelation was may be judged from a poem written more than thirty years later, when the poet’s boundary between private and public territories had been moved pretty far:

Hugerl, for a decade now

My bed-visitor,

An unexpected blessing

In a lucky life,

For how much and how often

You have made me glad.Glad that I know we enjoy

Mutual pleasure:

Women may cog their lovers

With a feigned passion,

But males are so constructed

We cannot deceive.

* * * And how much I like Christa

Who loves you but knows,

Good girl, when not to be there.

I can’t imagine

A kinder set-up: if mims

Mump, es ist mir Wurscht.

(“Glad”)

Auden’s later work preserved the element of enigma, in a tangential approach to surprising topics and with exotic words dropped casually into ordinary speech. But the tone remained the sort that members of a harmonious family take toward one another. So Auden holds us with agreeable modulations of language—from slang, to eloquence, from the colloquial to the technical—implying a privileged relation between him and ourselves. We respond to his candor, intimacy, faith in our sympathy. We stand with him against the Others.

Poems like “In Praise of Limestone” and “The Horatians” mix casual endearments or in-group signals with thoughts on aesthetics. In such poems Auden exposes his tastes and prejudices. He celebrates his landscapes, rises to sublimity, then stoops to the humble talk one uses with close friends or relations—and with oneself. But he stops consciously short of exhibitionism, perhaps just short: he veers away from scandal and indecency.

The efficiency with which Auden traveled about his poetic universe depended on a knack of dividing it up into classes or gradations between which traffic was convenient. It’s not for nothing that he wrote an ode to Terminus, the god of boundaries. From his early poems to his latest Auden approached his materials as a cataloguer.

He was eager to put things—morals, detective stories, mining machinery, God—in their proper places. Art, he wrote in “The Sea and the Mirror,” presents us with “the perfectly tidiable case of disorder.” So he tidied up the world like an affectionate housekeeper arranging a playroom for children: “To set in order—that’s the task / Both Eros and Apollo ask” (New Year Letter, 11. 56-57).

Advertisement

By a reflex action he seemed to arrange his important experiences as a collector of specimens would arrange rocks and minerals. He analyzed people and incidents into types that lent themselves to abstraction, illustrating principles of ethics or psychology. Sometimes he merely personified the categories, as in an attack on English society during the mid-Thirties:

Greed showing shamelessly her naked money,

And all Love’s wondering elo- quence debased

To a collector’s slang, Smartness in furs,

And Beauty scratching miserably for food….

(“Birthday Poem”)

This echoes Book IV of Pope’s Dunciad (11. 21-30). But Auden at his best did not stop at personification; he embodied the abstractions in curious or supreme examples. So when he wished to celebrate The Poet, he wrote magnificently about Yeats. When he wished to celebrate The Healer, he wrote almost as well about Freud. When he wished to celebrate a way of life, he identified it with the limestone landscapes he loved, and described some typical inhabitants of southern Italy (probably Ischia):

Watch, then, the band of rivals as they climb up and down Their steep stone gennels in twos and threes, at times

Arm in arm, but never, thank God, in step; or engaged On the shady side of a square at midday in

Voluble discourse, knowing each other too well to think There are any important secrets….

(“In Praise of Limestone”)

Auden’s best poems breathe, like this one, an air of self-confident control but a lack of self-importance. Like Dr. Johnson, the poet felt cheerfully communicative about matters which interested him: biology and morals, religion and ritual, geology, music, and Icelandic sagas. By fitting them into one of his schemes, the poet brought them into his family, even as he brought in the reader.

Auden’s father was a doctor, fond of archaeology and the sagas. His mother had been a hospital nurse, and was highly cultivated, religious, and musical. She would sing the part of Wagner’s Tristan, in the love-potion scene, to young Wystan’s Isolde. Auden’s elder brother John became a distinguished geologist. So the culture the poet disseminated in verse belonged to him by right of inheritance.

The impulse to classify may have sprung from Auden’s background too, but the poet’s use of the impulse was his own. Many of the poems entertain us through his habit of playing solemn games with his categories, especially with certain divisions between opposed sides. Auden liked to separate people—or creatures, or ideas, etc.—into mutually exclusive groups, each with its own rules; and he liked telling why they must remain apart. He would go on to treat the consequences of their separation, sometimes explicitly and sometimes cryptically.

But then he would also turn on himself by arranging a passage between the groups. Or he would call for a linkage, produced by means that happily transcended the principle of separation. As the reader takes in the game, he first enjoys discovering the scheme of oppositions and its rules; then he enjoys the benevolent dissolution or transcendence of both.

In the political poetry that Auden wrote during the Thirties, he used to divide the ranks of the oppressors from those of the oppressed and to invoke portents of revolution. But he naturally hinted that his own roots belonged to the former, that by a leap of sympathy he could still identify himself with the latter, and that in some sense love (charity, brotherhood, etc.) might make a bridge.

A wholly attractive instance is “A Summer Night,” in which the poet reflects on his good fortune as a member of a privileged circle and (in stanzas ultimately deleted) thinks of the “gathering multitudes outside / Whose glances hunger worsens”—those from whom he looks for a revolutionary explosion. Yet he still hopes that, as an ideal, the affectionate harmony of the old culture will survive the change and be a calming example for the new.

When the process of dividing and rejoining turns inward, we meet a poem like “Through the Looking-Glass.” Here the poet, celebrating Christmas with his family, longs for the presence of his secret lover, excluded from the domestic circle. So he dreams of a world naturalized to the forbidden love, in which the father, the mother, the poet, and the lover could all exist in harmony.

Thus Auden’s drive to establish and cross boundaries went beyond political and social classifications. It started from deeply moral concerns and easily took the form of psychological and religious distinctions: neurosis and health, faith and doubt. Regularly, the poet brought the distinctions to life by relating them to conflicts within the self and by inventing fresh images of transcendence. Even as he noticed the difficulty of crossing a frontier or of bridging a gap, he would insist the change had to be made.

Advertisement

This turn of mind led to another. Auden was struck by the way the commonplace hides the extraordinary, and the outside of things grows from and yet misrepresents their inside: “our selves, like Adam’s, / still don’t fit us exactly” (“Moon Landing”). Even a world that looks benign makes no response to human misery (“Musée des Beaux Arts”); and utter transformations of character may produce no visible change in one’s aspect or manner (“A Change of Air”). In “The Model” Auden deals with the rare instance of an octogenarian who looks as good as she is.

But the opposite case bothered him chronically: colorless lives whose essence is evil. In “Paid on Both Sides” ordinary people who buy Christmas turkeys willfully involve themselves in an insanely murderous feud: “these faces are not ours,” says the chorus. Similarly, “Gare du Midi” shows us a secret agent, come to destroy a city, who looks as nondescript as the train in which he arrived.

The persistence of the motif suggests that the poet was reflecting his own moral ambiguity. In “James Honeyman,” written when Auden was thirty, he described an ordinary man with a genius for chemistry, who hopes to invent a poisonous gas. As Honeyman walks out on Sunday, helping his wife to push the baby carriage, he says “I’m looking for a gas, dear, / A whiff will kill a man.” Thirty years later, in “Josef Weinheber,” Auden writes about “good family men” who keep watch, “devoted as monks, / on apparatus / inside which harmless matter / turns homicidal.” Ultimately, the problem of conversion, or of bowing to what is best in one’s nature, becomes the task of making the person be himself, closing the gap between inner and outer worlds.

I suppose there is a biographical explanation for such patterns; and it may also account for another feature of Auden’s work: the rendering of psychic states in terms of landscape. His imagery easily translated time into space, or changes in personality into changes of location. But the plain unfolding of the self in time seemed more of a challenge to him. At least, Auden handled it with effort, often framing it in the enormous map of phylogeny, or of the evolution of the universe. In a late poem, “The Aliens,” he surprisingly finds the metamorphosis of insects an utterly unhuman idea, although he well knew how commonly it has served as a metaphor of man’s spiritual history.

Movement in space, whether symbolic or “real,” seemed effortless for his imagination. He found it convenient to describe maturing as growing “taller” in his early poems. Later, he could talk about the shift from a worldly to a religious frame of mind as “A Change of Air”; or he could describe the aspiration to grace as “The Quest” of a hero in mythical regions.

A remarkable feature of Auden’s symbolic landscapes is the recurrence of certain elements: bleak, north of England scenery, with mines or mining equipment, often abandoned. The poet tells us that when he was a child, between the ages of six and twelve, he enjoyed elaborate daydreams of lead mining in a northern setting.

It is not hard to see, in the way Auden grew up, the origins of his fondness for landscapes in general and for certain scenes in particular. Even when he was little, he went on hikes and climbs in hilly places with his father and elder brothers. One summer in Wales the boys found a tannery, a ginger ale factory, and three river dams to occupy them.

The next year, the First World War broke out. Auden’s father joined the medical corps, Mrs. Auden gave up their house near Birmingham and sent her three boys to boarding school. Auden was seven; the fantasies had begun. When he was twelve, his father returned and the fantasies faded.

During the school vacations, while her husband was away, Mrs. Auden used to rent furnished rooms for the fatherless family in different parts of the country that had objects of interest to her children. They would all go on long walks together, observing the local scenery, architecture, and ancient industries. As Auden’s brother John put it, “We studied menhirs and stone circles, gold and lead mines, blue-john caverns, pre-Norman crosses and churches.”

I suppose the landscape of the boy’s daydreams was carried over from the rooted, united family of his preschool period; so it would have joined the wartime present to the harmonious past, and therefore would have comforted the quasi-orphan. The bleakness of the imaginary places and the depth of the mines suggest “objective correlatives” for the child’s loneliness, the father’s absence, the need to dig beneath the surface of the mother’s and the schoolmaster’s discretion.

Auden’s first published poem was about lead miners who toiled so that cathedrals might have roofs, and that the wealth gained might provide ornaments for a lady whose knights errant were seeking adventure in remote lands (“Lead’s the Best,” Oxford Outlook, 1926). Almost a quarter-century later, in a superb poem “Not in Baedeker,” Auden returned to the theme. Again the lead gave roofs to cathedrals; but no longer did it subsidize ornaments for ladies; instead, it became the linings of coffins, perhaps because Auden’s mother had died in 1941. The theme of the hero finding adventure abroad, while the beloved follows the usual routines at home, turns up in several forms, notably in “Who’s Who,” a neat, incisive comment on the blindness of love.

We do know that Auden tied his own character to that of his mother. There are verses and anecdotes to illuminate the sympathy between them:

Father at the wars,

Mother, tongue-tied with shyness,

struggling to tell him

the Facts of Life he dared not

tell her he knew already.

(Collected Poems, p. 602)

When Mrs. Auden went for long walks with her children, she sometimes accommodated herself behind a stone wall, invariably warning the boys not to watch. Young Wystan once asked, across the wall, what would happen if they did watch, and was told not to be cheeky. He went no further.

Auden described his mother’s family as quick, short-tempered, generous, and inclined to neurosis. She herself stood for eccentricity and fantasy; his father, for stability and reality. Dr. Auden was not conspicuously religious, and let his wife have her way in many things. Like both parents, the poet wanted to help and look after people; but he had a bossiness that does not seem paternal. His elder brother John reports that when Auden disapproved of someone’s behavior, he used to say, “Mother would never have allowed that.”

Didacticism and the impulse to set things in order are traits that encourage categorizing. To strengthen them, there were primitive dichotomies: the split in the self between the child who obeys his parents and the one who resists or ridicules them; or between the adult who labors openly at respectable tasks and the one who enjoys illicit pleasures in secret. Auden’s early work The Orators is built on such polarities.

They melt into others. Auden drew a line between the fortunate members of his privileged family and those excluded from it; and he dwelt on the distinction between the youngest (worst off, best off) son and his senior siblings. At school and in the constantly new homes of his vacations, I suppose the uprooted child would have elaborated such divisions; he would have translated them into maternal categories and used them to make his strange surroundings manageable and “familiar.”

Processes like these may have started Auden in his creative patterns, but his adaptations of them were the accomplishment of his genius. It was by a profound act of imagination that he brought the terrible events of four decades into his moral and psychological schemes. It was through high art that he mastered verse forms of pyrotechnic variety and matched them to his meanings. In his finest poems the housewifely, didactic impulse becomes merely the ground on which the inner self joins the outer, harmonized by the metrical design. “The Horatians” identifies the modern Anglo-American poet with the ancient Roman and uses a Horatian stanza. “In Praise of Limestone” mingles the character of the author with the rural landscapes he loved; and its elegiac distichs recall poets like Tibullus, who praised the country life in Italy.

As for Edward Mendelson’s edition of Auden’s Collected Poems, it is a triumph of exact scholarship. In general, the choice of poems and the texts exhibit Auden’s final judgments and revisions. Mendelson has allowed almost no misprints to disfigure this huge body of work, and he has painstakingly supplied dates of composition wherever possible.

Many readers will regret that Auden omitted or altered lines, stanzas, and whole poems that they remember with pleasure. (Several of those I have drawn on do not appear in the Collected Poems.) Since Mendelson worked under Auden’s instructions, he could hardly avoid an editorial policy that would have pleased the poet more than anyone else.

But most of the revisions could easily be defended; and those few poems which are here added to the canon must be called fascinating. In any case, the editor promises a further collection that will supply many of the present volume’s omissions. Meanwhile, only those who have tried their hand at textual scholarship will appreciate the intelligence, imagination, and energy that went into the preparation of the book.

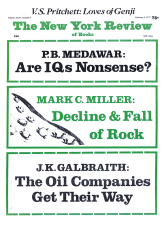

This Issue

February 3, 1977