For the White man, apartheid is a distance of mind, a state of being, the state of apartness. From the assumption of apartness—from the necessity to stress this apartness, to justify and rationalize it, to obscure that which may strip him naked—White culture in South Africa is born.

Apartheid works. It may not function administratively; its justifications and claims are absurd and it certainly has not succeeded in dehumanizing—entirely—the Africans, the Coloureds, or the Indians. But it has effectively managed to isolate the White man. He is becoming conditioned by his lack of contact with the people of the country, his lack of contact with the South African inside himself. Even though he has become a mental Special Branch, a BOSS of darkness, he doesn’t know what’s going on—since he can only relate to the syndrome of his isolation. His windows are painted white to keep the night in.

For the White author or artist it results in less contact with reality. He cannot dare to look into himself. He doesn’t wish to be bothered with his responsibilities as a member of the “chosen” and dominating group. He withdraws and longs for the tranquility of a little intellectual house on the plain by a transparent river. He cannot identify with anyone but his colleagues, any other class but his own White well-to-do one, and with this he probably identifies by default. His culture is used to shield him from an experience, or even an approximation, of the reality of injustices.

The White man has become brutalized. He can permit himself to reason away brutality. And in due course his sensitivity becomes blunted. Man lives through and in man. The writer, the artist who closes his eyes to everyday injustice and inhumanity, will without fail see less with his writing or painting eyes too. His work will become barren. When one prefers not to see certain things, when one chooses not to hear certain voices, when one’s tongue is used only to justify this choice—then the things one turned away from do not cease to exist, the voices do not stop shouting, but one’s eyes become walled, one’s ears less sensitive, therefore deaf, one’s tongue will make some decadent clacking noises, and one’s hands will only be groping over oneself.

The totalitarian regime existing in a hostile environment must draw the noose within which it protects itself from contamination ever tighter; it must continue to create new and more abominable laws, it must constantly redefine purity, or its cultural values—closely identified with its politics—are strangled.

AN APPEAL

…As friends of Breyten Breytenbach, we write to urge American readers to help him. We ask that protests be sent to Mr. Vorster and his ambassadors.

Gilles Deleuze, Girard Fromanger, Alain Jouffroy, Felix Guattari, Michel Leiris, Jacques Monory: Committee for Breytenbach, c/o Jouffroy, 105 rue Notre Dame des Champs, Paris 6; or c/o de La Falaise, 140 Fifth Avenue, New York City

—From “Vulture Culture,” an essay in Apartheid, edited by Alex

La Guma (International Publishers, New York, 1971).

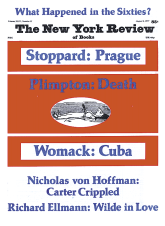

This Issue

August 4, 1977