In response to:

Mrs. M. and the Masses from the May 12, 1977 issue

To the Editors:

Professor John K. Fairbank (NYR, May 12) pleads with us, as many do nowadays, not to be concerned for human rights in China. “The fact is,” he writes, “that the human rights concept, though enshrined in a self-styled universal declaration, is culture-bound.”

I find Professor Fairbank’s argument faulty on two grounds: 1) his “fact” is open to doubt; 2) the legitimacy of concern for human rights does not depend on the universality, or otherwise, of the concept.

1) Professor Fairbank instructs us that the Chinese (all Chinese?), products as they are of “Buddhism as well as Confucianism,” are somehow basically averse to individual rights. But opinions vary among the experts on this point. Merle Goldman, in her book Literary Dissent in Communist China, tells us about a group of writers who were concerned “with individual rights in the face of an increasing monolithic society.”

We also know that the conformity of current Chinese life, so tremendously impressive to certain scholars in the West, has to be enforced with tremendous violence and cruelty against opposition from the people. Martin King Whyte, in Small Groups and Political Rituals in China, gives us details of the corrective labor camps and their inmates. Richard Walker, in The Human Cost of Communism in China, gives an overview of the terror under which millions have died. Some readers will be tempted to dismiss Professor Walker’s judgments because they have appeared under conservative auspices; but this will be more difficult for Regards froids sur la Chine, edited by Claude Aubert, et al., which is the work of French left-wing intellectuals, and which confirms the totalitarian character of the Maoist regime.

Professor Fairbank may well be right when he talks of the opposition of the elite to notions of human rights: “…a selected elite committed to governing…cannot be expected to embrace a foreign and essentially bourgeois creed of civil liberties.” But what about those Chinese, surely the vast majority, who do not happen to be members of the ruling elite? Those in the labor camps, surely, and those who have lost family members in the purges, can they be presumed to be as enthusiastic about the forced conformity as are certain Western professors?

2) What could Professor Fairbank possibly mean when he asserts that the concept of human rights is “culture-bound” rather than universal? In one sense, at least, human rights cease being universal the moment a human rights issue arises; those who do the denying of such rights cannot, in the nature of these things, agree with those who are being denied. Had the white rulers of South Africa accepted human rights for blacks, no problem of human rights would have arisen in the first place.

Concern for human rights, always and invariably—whether in New York or Nanking—means taking sides against one group of people and for another. Those of us who are concerned always worry about victims and always find ourselves in conflict with those who do the victimizing. To indicate that the Chinese Communist elite thinks of us as “bourgeois” or whatever—or to lecture to us about “Buddhism as well as Confucianism”—does not answer the argument of the forced labor camps and the millions of purge victims.

Werner Cohn

The University of British Columbia

Vancouver, Canada

John K Fairbank replies:

Beat the bearer of bad tidings! It seems like old times. Those who in 1946 foresaw the communist victory in China were later felt to have caused it. My suggestion today that the human rights concept is culture-bound and not native to China, leads Professor Cohn to conclude that I am not concerned about it. “What can I possibly mean?”

I mean that the Chinese cultural tradition differs from the European. It stresses one’s moral duty, and China has a noble list of martyrs who did their Confucian duty to remonstrate with evil rulers. It stresses the collective good, and Buddhism and Confucianism (which are no more nonsensical than Christianity) taught self-control and self-sacrifice as the individual’s highest duty. It does not say much about individual rights, and so the victimized person has little precedent or sanction for protest.

Of course, many modern-minded Chinese, especially Western-trained scholars, writers and artists, have suffered tremendous frustration and often been egregiously victimized in the course of the revolution. Let us help them if we can. But before we see the world as simply a struggle between freedom and totalitarianism in which we bear the universal truth, let us size up the problem realistically: do we back Mr. Carter to inveigh against injustice everywhere, or is “human rights” a more specific operational concept (like “civil liberties”) involving due process of law? The fact is that habeas corpus, presumptive innocence, right of counsel, no self-incrimination, jury trial, and other civil liberties depend on the supremacy of law. But Chinese tradition and practice do not accept the supremacy of law even to the extent that Russia does. The Chinese do things a bit differently, usually with more concern than we have for moral conduct and less for legal rules.

I submit that we have homework to do before we start crusading.

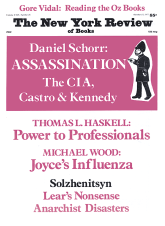

This Issue

October 13, 1977