There was such a dense concentration of energy there, American and essentially adolescent, if that energy could have been channeled into anything more than noise, waste and pain it would have lighted up Indochina for a thousand years.

It is more than ten years since Lyndon Johnson told the Vietnamese he had American energy enough to move the New Deal from the Pedernales to the Mekong. Michael Herr, who, when he was himself essentially adolescent, wrote the sentence above, loves that energy, and wants Dispatches to be the Vietnam book that will light up the literature of war for something like a thousand years. Though more than half of his book was published between 1968 and 1970, Herr fussed and rewrote and added—this was to be the book about the war that no one else had written. The results are odd, painful, superb in many places, commonplace in many others.

While in Vietnam Herr preferred to say he was a writer rather than a reporter. The soldiers could not have cared less about such a distinction since they knew that anyone who was in Vietnam by choice was mad. It mattered to Herr, though. His assignment was indefinite, he never had to listen to press briefings or trace down the lies of the generals, he did not have to file daily or weekly stories, to stay in one place, or to go where some editor, listening to the lies, told him to go. His impulse was like that of the young Norman Mailer, who wanted to go to the Pacific in 1942 since the great book about World War II would be laid there. He wanted to emulate George Orwell. “There was a special Air Force outfit that flew defoliation missions. They were called the Ranch Hands, and their motto was, ‘Only we can prevent forests.’ ” That is what Herr wanted to write about, American energy, wit, and brutality.

His first effort, in 1969, “Hell Sucks,” for Esquire, has been cannibalized until little more than the title remains, but the other long pieces he wrote in Vietnam appear here pretty much as they were originally published. One sees why Herr wanted to make changes, and also why he ended up changing so little. This is a fairly typical vignette from “Illumination Rounds”:

A twenty-four-year-old Special Forces captain was telling me about it. “I went out and killed one VC and liberated a prisoner. Next day the major called me in and told me that I’d killed fourteen VC and liberated six prisoners. You want to see the medal?”

This is shorter than most, but most of his observations are similarly pointed to display The Idiocy of War, The Terror of War, The Arrogance of Americans, or some such motto. ” ‘You guys ought do a story on me suntahm,’ the kid said,” because, he goes on, ” ‘I’m so fuckin’ good.’ ” Or, “I met this kid from Miles City, Montana, who read the Stars and Stripes every day, checking the casualty lists to see if by some chance anybody from his town had been killed,” since he figured to stay alive if there was, because ” ‘I mean, can you just see two guys from a raggedy-ass town like Miles City getting killed in Vietnam?’ ” The central scenes in Herr’s long dispatch from Khe Sanh even feature two grunts, one black and one white, buddies, named Mayhew and Day Tripper, and might have been written for a Stanley Kramer movie.

Some of this writing is vivid, but of a sort that conforms all too closely to our idea of what a very young writer in Vietnam might write. The callowness reaches an apotheosis of sorts when Herr describes hearing “an electric guitar shooting right up” in the middle of a rice paddy, “and a mean, rapturous black voice singing, coaxing, ‘Now c’mon baby, stop actin’ so crazy’ “:

That’s the story of the first time I ever heard Jimi Hendrix, but in a war where a lot of people talked about Aretha’s “Satisfaction” the way other people speak of Brahms’ Fourth, it was more than a story; it was Credentials. “Say, that Jimi Hendrix is my main man,” someone would say. “He has definitely got his shit together!”… That music meant a lot to them. I never once heard it played over the Armed Forces Radio Network.

Lord knows where one could find anyone speaking of Brahms’s Fourth that way, and almost certainly it is either Jagger’s “Satisfaction” or Aretha’s “Respect” that Herr means here. What is limiting, though, is the gauche pointedness of the writing, the surprise of hearing Hendrix’s singing in a rice paddy muffled into a message about an essentially adolescent white boy getting his credentials, while the Armed Forces Radio Network will never have theirs.

Advertisement

After Herr returned home he seems to have sensed something of this sort. Yet, at home, it was all different—“Out on the street I couldn’t tell the Vietnam veterans from the rock and roll veterans”—and Herr feared he would only ruin what he had already written. So he tried to write something different, and if it was this effort that led to the opening section, “Breathing In,” I am glad he worked so long at it, for that section is the wonder of the book. Here there is much less reporting and fewer vignettes, because what Herr is aiming for is a sense of confusion, acid head frenzy, fear distilled into a kind of nostalgia. Mention a helicopter and Herr is off into a kind of reverie:

In the months after I got back the hundreds of helicopters I’d flown in began to draw together until they’d formed a collective meta-chopper, and in my mind it was the sexiest thing going; saver-destroyer, provider-waster, right hand-left hand, nimble, fluent, canny and human; hot steel, grease, jungle-saturated canvas webbing, sweat cooling and warming up again, cassette rock and roll in one ear and door-gun fire in the other, fuel, heat, vitality and death, death itself, hardly an intruder.

The writing has heated up, but Herr creates the kind of jumble in which horror, surprise, and excitement all come together.

The reverie then modulates effortlessly:

Flying over jungle was almost pure pleasure, doing it on foot was nearly all pain. I never belonged in there. Maybe it really was what its people had always called it, Beyond; at the very least it was serious, I gave up things to it I probably never got back…. Once in some thick jungle corner with some grunts standing around, a correspondent said, “Gee, you must really see some beautiful sunsets in here,” and they almost pissed themselves laughing. But you could fly up and into hot tropic sunsets that would change the way you thought about light forever. You could also fly out of places that were so grim they turned to black and white in your head five minutes after you’d gone.

No ground rules have been laid down, so Herr’s breathiness becomes the experience, and all the meaning that apparently can be had. Saigon comes in for its own extended reverie, appearing as the place where everyone was stoned and everything was depressing; so too does the Têt offensive, the turning point of Herr’s war, but these places and events are left displaced, understood but not in any pointed way. The integrity of memory is Herr’s ally in showing him he has truths but no message.

Thus this reflection which he could never have written at the time he was there:

Every day people were dying there because of some small detail that they couldn’t be bothered to observe. Imagine being too tired to snap a flak jacket closed, too tired to clean your rifle, too tired to guard a light, too tired to deal with the half-inch margins of safety that moving through the war often demanded, just too tired to give a fuck and then dying behind that exhaustion.

It forms the perfect introduction for a vignette:

One afternoon at Khe Sanh a Marine opened the door of a latrine and was killed by a grenade that had been rigged on the door. The Command tried to blame it on a North Vietnamese infiltrator, but the grunts knew what had happened: “Like a gook is really gonna tunnel all the way in here to booby-trap a shithouse, right? Some guy just flipped out is all.”

There’s no way Herr’s earlier reporting of the adventures of Mayhew and Day Tripper could have set up that shocking little story. Writing much later, Herr can see how to give the incident the right setting so that it shocks, but one sees why the grunts were not shocked. That, in turn, leads to this distilled conclusion about the frustration, madness, and callousness of all that energy:

Some people just wanted to blow it all to hell, animal vegetable and mineral. They wanted a Vietnam they could fit into their car ashtrays; the joke went, “What you do is, you load all the Friendlies onto ships and take them out to the South China Sea. Then you bomb the country flat. Then you sink the ships.” A lot of people knew that the country could never be won, only destroyed, and they locked into that with breathtaking concentration.

Though he is not more than sixty pages into Dispatches when he writes this passage, Herr has managed to make such joking and such concentration comprehensible in ways that a score of stories or a long novel might not have been able to do as well.

Advertisement

I hope I have managed to indicate how obscene Herr makes the war seem, especially in his splendid opening section. It is not that he makes no judgments, but that he renders the welter of the concentrated madness so close up that the relevance of the judgments is clear for a moment, then obscure; that is the message Herr’s memory finally yielded him. Every review of Dispatches I have seen pays it the proper respect of trying to fit in as many quotations as it can, because Herr at his best hurls one into his experience, insists an uninitiated reader be comforted with no politics, no certain morality, no clear outline of history. After I finished his book I re-read a hundred pages of Frances FitzGerald’s Fire on the Lake, which has been accepted as one kind of good book on Vietnam. Alongside Dispatches, FitzGerald’s book, with its clarity, its balanced views, its intelligent laying out of the evidence, was the one that seemed, in its neat detachment, obscene. At his best at least, Herr shows and reminds us there are some things we had best not pretend to understand with such ease.

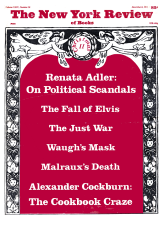

This Issue

December 8, 1977