In response to:

The Holes in Black Holes from the September 29, 1977 issue

To the Editors:

There is a great danger in asking one person—however brilliant—to review seven books simultaneously. It is possible, perhaps even likely, that not all of the books will be read with quite the same loving care that would be lavished if the reviewer were dealing with them individually. This seems to have happened with Martin Gardner’s recent review (NYR, September 29) of a bumper bundle including my own White Holes, and I would be grateful for the opportunity to comment on his rather strange remarks.

It is, of course, the reviewer’s privilege to choose to comment not on my current book but on a book published three years ago on a totally unrelated topic, The Jupiter Effect. I am pleased to learn that Gardner has at least read one of my publications. But his comments on White Holes are ludicrous.

Even from the passage on spoon bending quoted, any intelligent reader—such as a typical reader of your journal—must surely realize that my comments on tachyons and spoon bending are presented tongue in cheek. It is, Mr. Gardner, a joke. May I quote the sentence which immediately follows the paragraph Gardner chose to quote: “So much for science fiction….” Even the unintelligent should realize from these words, had they been read at all, my opinion of the bent-spoon cult.

If Gardner has any serious comments on the book, I would like to hear them. For now, in view of the incompetence of his so-called “review” I feel that the least you could do is ask someone—anyone—actually to read the book and then to provide a genuine review which does not present as my own beliefs ideas which I have discussed only in order to hold them up to ridicule myself.

John Gribbin

The University of Sussex

Sussex, England

Martin Gardner replies:

Mr. Gribbin quotes only the first half of the sentence which he says proves that the passage I quoted was intended as a joke. The complete sentence is: “So much for science fiction, for the time being at least.”

Now this sentence is not sufficient to establish that the theory Gribbin presented—tachyons as an explanation for psychic spoon bending—was intended as a joke. The reason is simple. Eighty percent of the theories discussed in White Holes are “science fiction, for the time being at least.” The notion that some day we may be able to rocket around the universe by going in and out of black and white holes is science fiction at its wildest. Indeed, the very concept of a white hole is “science fiction, for the time being at least.”

Does Gribbin consider tachyons a joke? In his book’s introduction Gribbin writes: “The concept of tachyons—those faster-than-light particles—has not yet gained general acceptance…. How long will it take, I wonder, before this new imaginative leap is used by sober engineers to design communicators with which we can transmit and receive messages that traverse the Galaxy faster than the speed of light?”

To send a message faster than light means sending it back in time, and this leads directly to logical contradictions. If A sends a tachyonic message to B, in another galaxy, and B replies tachyonically, then A gets the reply before he sent the message. Gribbin nowhere mentions this well-known paradox, which renders tachyons (if they exist) useless for communication, but perhaps he knew about it all along and intended his remarks on tachyons to be taken as tongue in cheek.

It is good to know that Gribbin regards psychic spoon bending as a joke, and that his several pages about it (with many references to his colleague John Taylor who wrote an extremely serious book on the “Geller effect”) are there only to hold spoon bending “up to ridicule.” But now I am puzzled about the rest of the book. Can it be that Gribbin also intended to hold white holes up to ridicule, and that his entire book is a joke?

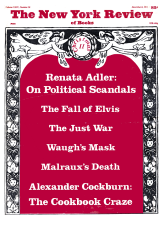

This Issue

December 8, 1977