Patrick Leigh Fermor is renowned for his exploits in Crete during the war. Together with his companion Xan Fielding, he captured the German commander of the island, General Kreipe. During periods when, disguised as Cretan shepherds, they were in hiding, they exchanged reminiscences of their prewar boyhoods. A Time of Gifts, which is dedicated to Fielding, is the result of these recapturings of time past. It recalls a journey which Leigh Fermor made in 1933, going on foot from London to Constantinople. He was eighteen years old and had just been expelled from the Crammers, where he was at school.

But the book is much more than that, and might be described as a prose poem in which the writer, forty years after the events described, re-creates a journey which is partly real, partly symbolic, a journey from boyhood to manhood. It was perhaps in some sense a test of the boy who had failed and who imposes on himself difficulties over which he must triumph. The double nature of this journey is shown in the introductory letter to Xan Fielding, when Leigh Fermor recalls the moment of vision in which he decided to make it:

Even before I looked at a map, two great rivers had already plotted the itinerary in my mind’s eye: the Rhine uncoiled across it, the Alps rose up and then the wolf-harbouring Carpathian watersheds and the cordilleras of the Balkans; and there, at the end of the windings of the Danube, the Black Sea was beginning to spread its mysterious and lopsided shape; and my chief destination was never in a moment’s doubt. The levitating skyline of Constantinople pricked its sheaves of thin cylinders and its hemispheres out of the sea-mist; beyond it Mount Athos hovered; and the Greek archipelago was already scattering a paper-chase of islands across the Aegean. (These certainties sprang from reading the books of Robert Byron….)

So there are two maps, the imaginary and the real. But the real provides confirmation of the imaginary, the itinerary envisioned. Leigh Fermor has a mind capable of imagining vast expanses of geography and history, but, however fantastic these visions communicated in his exuberant rhetoric, they are realizable as actuality. The journey provided the transition from boyhood to manhood by demonstrating that the map inside the mind could be projected onto the geographical landscape by the physical body. This connection between boyhood and manhood was essential to him and the reasons for this are to be found in his childhood, of which he provides a very vivid and amusing preliminary account.

Born early in the First World War, he was left in England by his parents—his father being in the Indian government. Leigh Fermor was billeted on “a very kind and very simple family” of farmers who let him run so wild that he was unfit for “the faintest shadow of constraint.” After this, he was sent to progressive schools, whose greensward libertarianism he describes hilariously. He proved intractable even by their empathetic standards. In intervals of bounding over hills, breaking through forbidding barriers, and chasing Maids Marian, he read enormously. He attributes his troubles at school to “a bookish attempt to coerce life into a closer resemblance to literature…abetted by…a hangover from early anarchy.” The journey shows how life could, after all, be a confirmation of the truth of literature, and the anarchy be converted into effective energy.

There is something Kiplingesque about this, the magical Kipling of Roman encampments and fairyland in Sussex woods—the Kipling who can combine imagination with action. A psychoanalyst might have a good deal to say about it, yet fail to detect a frustrating neurosis. In fact there seems to be the opposite of neurosis—relief. Leigh Fermor and Fielding, disguised in their shepherd garb and reminiscing, agreed that “the disasters which had set us on the move had not been disasters at all, but wild strokes of good luck.”

The title “A Time of Gifts” is quoted from a poem called “Twelfth Night” by Louis MacNeice, about loss of innocence (“O boys that grow, O snows that melt”). The narrative also recalls early poems by Auden in which heroes undergo legendary journeys in pursuit of a goal which is “the Quest.” The map on which the young Leigh Fermor plots his itinerary is that of a mythical journey as well as a real one. The mountains, plains, rivers, villages, castles he encounters both have their real existence and are illustrations of the mythical journey. His knowledge of paintings which to him already seem illustrations of the life of places where they were painted stresses this. The reader has the sense of places constantly turning into the history that happened there, the pictures which artists made of the scenery and inhabitants. Leigh Fermor sets out from the port of London in midwinter—December—which seems an ill-chosen season for campaigning, but the decision greatly adds to the effect of illustration, as one realizes when he gets to Holland where it is snowing:

Advertisement

Ever since those first hours in Rotterdam a three-dimensional Holland had been springing up all round me and expanding into the distance in conformity with another Holland which was already in existence and in every detail complete. For, if there is a foreign landscape familiar to English eyes by proxy, it is this one; by the time they see the original, a hundred mornings and afternoons in museums and picture galleries and country houses have done their work…. The nature of the landscape itself, the colour, the light, the sky, the openness, the expanse and the details of the towns and the villages are leagued together in the weaving of a miraculously consoling and healing spell.

In the journey which is a quest, certain conditions are binding. Equipment must be minimal: rucksack, tramping clothes, an ash plant stick (which Leigh Fermor covers “obsessively” with little metal disks obtained at villages and denoting the places he has been to). Money must be adequate only for bare necessities, and, as far as possible, the whole journey must be made on foot. The journey takes the hero through a landscape inhabited by paupers, peasants, and boisterous innkeepers whose wives and daughters take pity on the youth. At the very bottom of the social ladder, in doss houses, eccentric strangers are met. These insulted and injured yet have the courtesy of natural aristocrats. The most entertaining and moving stranger of this kind is Konrad, son of a Frisian pastor, and much come down in the world, who addresses Leigh Fermor in an English he has learned from reading Shakespeare, greeting him when they wake up in the quarters allotted to tramps in Vienna with the words: “I hope your slumbers were peaceful and mated with quiet dreams?” Konrad’s own dream is to acquire enough capital (which Leigh Fermor is later able to provide, it being only one pound sterling) to buy quantities of aspirin to smuggle across the Austrian frontier.

Apart from some of the subjects of the drawings Leigh Fermor made for small fees, this is a world almost devoid of an urban middle class: but, besides the peasants, beggars, and innkeepers, there are princes and princesses who occasionally waft the hero from pallets of straw in barns or truckle-beds in inns or youth hostels to lavishly furnished rooms in castles. Introductions have been provided in London, and Leigh Fermor uses one of these (most fortunately, since his rucksack, together with his journal, has been stolen at the youth hostel where he stayed the previous night) to betake himself to Baron Rheinhard von Liphart-Ratshoff, who invites him to stay in his castle at Gräfeling, near Munich. This delightful family, White Russians, replaces the rucksack and most of its contents and provides Leigh Fermor with a duodecimo mid-seventeenth-century edition of Horace to put in it. They also give him introductions to other owners of castles, so that his journey from now on becomes a series of ascents to the topmost peaks and descents to the lowest depths of society. It is significant though that he is never dressed for the part of visitor to the great establishments. He is the Wandervogel pilgrim at the gates whom it is their blessing to invite in.

This is not a journey in which the hero, Rilke-like, is exploring his own inner life. Nor is it one in which he is discovering realities of sex and current politics. In the introductory chapter, Leigh Fermor notes that he rejected any idea of enlisting a companion: “I knew that the enterprise had to be solitary and the break complete.” It is a voyage of self-discovery but by an extrovert. Leigh Fermor until the end of the present volume which takes us to Hungary remains prelapsarian. He is aware of the charm of girls but they seem like figures in a landscape: nothing happens with them. His encounters with politics are like those of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern in Tom Stoppard’s play. Occasionally storm troopers from the debased Hitlerian court rush across the scene with their odor of fire and brimstone. Leigh Fermor loathes them, but even more he is puzzled by these interruptions. Quite early on he is sitting in a German inn, anticipating friendliness, when he notices a lint-haired young man with pale blue eyes “fixing me with an icy gleam.”

He suddenly rose with a stumble, came over, and said: “So? Ein Engländer?” with a sardonic smile. “Wunderbar!” Then his face changed to a mask of hate. Why had we stolen Germany’s colonies?

The young man is led away “and the hateful moment was soon superseded by feasting and talk and wine, and, later, by songs to usher in St. Sylvester’s Vigil.” One notes that the moment is hateful, not the young man, whom Leigh Fermor is evidently prepared to regard as someone quite nice who is seized momentarily by an evil Zeitgeist. And this is quite right. His book belongs to another time, of the past and legend. One is extremely grateful that it does not end with him becoming an anti-Nazi, as, looking back, he seems at one moment to feel rather ashamed at his not having done. For just when Konrad and he were scraping groschen together in Vienna, the socialist rising at the Karl-Marx-Hof was being liquidated by the Dollfuss government. He comments:

Advertisement

As everything in the mood of the city conspired to reduce the scale of events, it was easy to misunderstand them and I bitterly regretted this misappraisal later on: I felt like Fabrice in La Chartreuse de Parme, when he was not quite sure whether he had been present at Waterloo.

But Ernest Hemingway once said he thought that Stendhal’s account of Fabrice wandering about lost and dazed on that battlefield was the best description of war ever written. I would not deduce from this that Leigh Fermor is strong on conveying the atmosphere of the Thirties, yet it is very interesting to know that a young Englishman walking from Holland across Germany to Vienna in late 1933 and early 1934 found, in villages and in provincial towns and on farms, so much continuity of traditional life beyond which political events were “intermittently rumbling in the distance like stage thunder.”

Earlier on I quoted Leigh Fermor writing of himself at school as making “a bookish attempt to coerce life into a closer resemblance to literature.” His journey was partly a continuation of such an attempt and partly an abandonment, or rather a resolution, of it. What he does, with the aid of a technique based on his bifocal vision as a man entering into the state of mind of the boy whom he was forty years previously, is to interpret landscape and architecture by the exercise of an imagination which connects the bookish and painterly visionary map with the real map. And the connection is achieved physically with his body which, with head still full of the visionary map, walks across the real one. In doing so, he makes the reader feel that pictures and architecture are extensions of the lives of people who live in a history and a landscape—enormously powerful realizations of them—into which he can mentally and, indeed, almost physically enter. After seeing the great baroque Austrian monastery at Melk, he launches forth into an excursus on the development of such architecture which really does give a feeling of art and architecture animated by the human spirit in contact with nature, history, religion:

A versatile genius sends volley after volley of fantastic afterthoughts through the great Vitruvian and Palladian structures. Concave and convex uncoil and pursue each other across the pilasters in ferny arabesques, liquid notions ripple, waterfalls running silver and blue drop to lintels and hang frozen there in curtains of artificial icicles. Ideas go feathering up in mock fountains and float away through the colonnades in processions of cumulus and cirrus.

Leigh Fermor has a great sense of the genius animating forms, which, in his mind, are continually transforming themselves back again from stone and marble, cathedral and castle, returning to the spirit of people who animated them. One of the most interesting passages in the book is that in which he outlines the theory which comes to him after he has been looking at a color plate of “Landsknechts in the time of the Emperor Maximilian I.” He calls the “Landsknecht formula” the idea of “medieval solidity adorned with a jungle of inorganic Renaissance detail,” which proliferates everywhere, in heraldry, clothes, armor, iron work, typography: “everything that could fork, ramify, coil, flutter, fold back or thread through itself, suddenly sprang to action. Clocks, keys, hinges, door-bands, hilts and trigger-guards…centrifugal lambency and recoil! The principle is active still.”

The fact that a book as spirited as this can be written today seems almost a miracle. And yet it is also encouraging, because it reminds us that there is probably at this moment a young man hitchhiking or journeying somewhere, pursuing the goal of the quest, and as passionately identifying the most vigorous life in his own body with expressions which he sees in art and architecture, and as impervious to politics, as the young Patrick Leigh Fermor of 1933. He is the wandering scholar and the not-too-monkish monk.

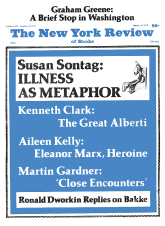

This Issue

January 26, 1978