When lo! a burst of thunder shook the flood.

Slow rose a form, in majesty of mud,

Shaking the horrors of his sable brows,

And each ferocious feature grim with ooze.

Greater he looks, and more than mortal stares;

Then thus the wonders of the deep declares.

[The Dunciad, 2.325-330]

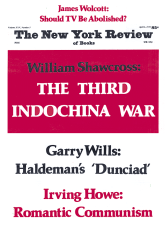

Haldeman’s book was supposed to “tell all” and he tried hard at it—he tells us more than he knows, and hints at more than he tells. He also manages to include just about everything said by just about everyone involved in or looking at the tangle of Watergate events.

He agrees with Nixon’s defenders in all their countercharges. He takes the Victor Lasky-William Safire line that “it didn’t start with Watergate.” He also thinks, with Raymond Price and Pat Buchanan, that press enemies and Democrats drove him to it. He concludes that Watergate was a Democratic trap, sprung by Larry O’Brien’s dirty tricks and closed by John Doar’s dirtier ones.

Haldeman justifies the secret bombing of Cambodia on the grounds that mean kids in the street wouldn’t let Nixon commit his patriotic acts in daylight. And since the kids were being manipulated by communists (pp. 106-107), that means the President of the United States was a captive in his own house of the enemies he was trying to bomb with honor in a distant land. No wonder he had to sneak and cover his nobler moments. With William Buckley, Haldeman thinks any president would be forced to hire gumshoes like Howard Hunt in a nation that gives its Pulitzer Prize to Jack Anderson. (Anderson, of course, was part of the Democratic trap in Haldeman’s reading of Watergate.)

But after attacking all Nixon’s enemies, Haldeman turns around and embraces all their theories too. So far as conspiracies are concerned, it is “come one come all” for Haldeman.

To him the Goddess: “Son! Thy grief lay down,

And turn this whole illusion on the town.”

[2.131-132]

He holds the Terry Lenzner-J. Anthony Lukas view that the DNC break-in came from Nixon’s desire to know about Larry O’Brien’s ties with Howard Hughes (and to know what O’Brien knew about Hughes’s ties with Nixon and Rebozo). Haldeman gives himself too much credit when he calls this “my own theory of what initiated the Watergate break-in.” But he admits Daniel Schorr supplied him with a CIA theory of Watergate (one prompted, as well, by Ehrlichman’s novel, The Company). Then he adds curlicues to that theory from Miles Copeland, Howard Baker, and Fred Thompson.

Haldeman agrees with Nixon’s critics that the tapings were for “blackmail” purposes—especially useful for keeping Kissinger in line. Haldeman also welcomes all variants—those of Nicholas Von Hoffman, Renata Adler, Edward Jay Epstein—of the “bureaucracy” theory of Watergate. The more people getting in on the kill, the better for Haldeman: it shows Nixon was right to see everyone (except Haldeman) as an enemy.

Haldeman, Haldeman tells us at length, was not Nixon’s enemy, just Nixon’s dupe. He lives, like his master, in a Hobbesian bellum omnium contra omnes—and his only mistake was not to see that Nixon was his enemy, like everyone else. The Nixon White House looms darker in this book than in anything written by Woodward and Bernstein. Nixon is not drunk at night, just so tired he cannot talk or walk straight. It is a wearying task, this daytime pretense at being “nice Nixon.” Haldeman tried to put him back into his coffin every night before “nasty Nixon” got a chance to burble evil plans to someone like Chuck Colson. Ehrlichman loves to be devious. Kissinger is an egomaniacal paranoid. Butterfield may be a CIA plant. Haig believes in wild Jewish plots. Buchanan overheats Agnew. Even Pat Nixon is given a slap for her taste: Nixon “warned me that…Pat would decorate the office for him. Eventually she did it in bright blue and yellow because she wanted it to be ‘cheerful.’ ” Everybody “gets theirs” in this book.

Everybody, it is said, but Haldeman. That is not quite true. Haldeman admits to one mistake (trusting Nixon) and one fault (giving Colson access to Nixon). Not much: but you have to remember that anyone who exposes even partially a mind so fetid with distrust cannot be accused of self-flattery. Haldeman’s convenient lapses of memory are by now standard in the treatment of Watergate. He presents most of the White House “horrors” (in John Mitchell’s term) as reactions to outside aggression—the “kids” were tying the president’s hands; people were stealing Pentagon Papers right out from under the government’s nose; nobody would cooperate with Nixon (Haldeman thinks the IRS was being used by Democrats to “get” conservatives). When he sees occasional excess, it comes as a surprise to him—John Caulfield says that Colson wants the Brookings Institute fire-bombed, Nixon himself sends Caulfield to tap Joseph Kraft’s telephone. Haldeman does not tell us why Caulfield was there in the first place. Like most people, he begins the horrors too late to explain them properly.

Advertisement

Who remembers Tony LaRocco? Not many people, I’ll bet you. He never got around to doing much in the spy line of work for which he was hired—but that made him something of a symbol for me. He demonstrated the early desire to have gumshoes hanging around “just in case.” He shoots down the whole idea that Nixon was responding to prior aggressions. For Tony LaRocco was hired in December of 1969, and paid from the secret White House fund, just to be ready. He was brought on before there was any actual work for him to do.

He was acquired through Caulfield, who had been hired in March of 1969—less than two months after Nixon entered the Oval Office. Ehrlichman arranged for Caulfield’s payment from the Kalmbach fund—but Haldeman had interviewed him for his first job (security during the 1968 campaign) and recommended him to John Mitchell. When Mitchell did not hire him, he went on the private payroll; and though Ehrlichman put him there, William Safire remembers him as the “Haldeman surveillance man” (After the Fall, p. 298) and John Dean says Haldeman assigned Caulfield to his office (Blind Ambition, p. 35). It is clear that Haldeman and Ehrlichman wanted their own secret hit men long before Colson arrived on the scene—and before the drug team was formed from which Edward Jay Epstein dates the Watergate madness. This was, as well, before “theft” of the Pentagon Papers gave the White House an opportunity to put “plumbers” on the public payroll—an excuse for alternate financing, not a first occasion for political spying. The spying began in earnest after Chappaquiddick, when Caulfield sent Tony Ulasewicz to dig up dirt on Edward Kennedy. That was during Nixon’s first summer in office.

Every memoir from the White House testifies to Nixon’s obsession with Kennedy, and his willingness to use any weapon against him. Once again, Haldeman associates this primarily with Colson, who had his own grudges against Kennedy from days in Senator Saltonstall’s office. But the Chappaquiddick capers were going on before Colson had acquired any power in the White House. Haldeman admits that Colson gained power over Nixon by boasting of “dirty tricks” performed on his behalf. Did Haldeman and Ehrlichman perform the Chappaquiddick tricks and take no credit for them where they knew they would be most appreciated? Haldeman and Ehrlichman knew how to please their master—who, in turn, clearly knew about this secret team. Haldeman says that Nixon himself ordered Caulfield to tap Kraft’s phone. How did he know Caulfield was available for such missions? Obviously from the man who hired him in the first place, from Haldeman.

Haldeman says Nixon had to resort to private financing of secret agents because the bureaucracy had resisted his orders to find the communists at demonstrations, plug the leaks, tap phones, etc. But there had been no time to test that resistance when Caulfield and Ulasewicz were hired—and, later, Tony LaRocco was added to the team (and, later, Hunt et al.). There was a prior determination to use sneak thieves for missions so mean and personal that no one could be trusted to know about them but the little Oval Office triumvirate. The fungus, thus in place, was bound to spread.

It was a blessing to the nation that Nixon could trust no one. Those who accuse him of politicizing the IRS or of an attempted coup on the CIA and FBI do not realize that he was too frightened of those agencies to let them in on his real vindictiveness. He was an amateur at coups; Tony Ulasewicz was more his speed than Richard Helms. That is why, eventually, he got caught. The bureaucracy did not react, in fear of his reorganization plan, all of a sudden in 1973. Nixon had been laying up powder for his own destruction all through the years of secret little crimes, of buggings and break-ins and a growing band of bumbling crooks tiptoeing in and out of the White House.

Nixon’s distrust of others was fully shared by Henry Kissinger; and the hallmark of their diplomacy was secrecy. Not only was Congress to be kept in the dark; so were the State Department and the Pentagon. The secret bombing of Cambodia, the secret mission to China, the secret peace initiatives, the secret motive for the Christmas Bombing—all these represent attempts to run the world out of the White House, letting few others in on the act.

Advertisement

Here we get, I think, the explanation for Haldeman’s bizarre claim that Nixon secretly averted war on two occasions—when he bluffed the Russians back from China’s border, and threatened Russia out of its Cuban submarine base. The feints and counterfeints of diplomatic intelligence gave Haldeman some slim basis for those exaggerated claims. But who did the exaggerating? Haldeman himself? I think he is relaying the fantasies of his master—which would explain the confidence with which he puts forth a thesis instantly denied by Secretaries Kissinger and Rogers, as well as by the Russians. Nixon liked to think he was saving the world all by himself, in ways that no one knew. It is important to remember that Haldeman was talking with Nixon about the president’s book right up to the Frost interviews, which made him cease, but only in part, from the role of Nixon’s alter ego. The bunkered Nixon still speaks through his puppet about the ways he saved the world.

All the White House memoirs—even that by the dogged loyalist, Raymond Price—talk of a good Nixon and a bad one, of a light side and a dark side. (Each author, of course, claims that he was there to make the light side prevail.) But the Nixon of the secret mission to China was not so distant from the Nixon who dispatched a spy team to Chappaquiddick. Price becomes an object lession in the way good Nixon could use deviousness to involve others in mendacity. Price wrote the white papers and speeches Nixon used to exculpate himself in the coverup period. Price was lied to by his boss, then helped him lie to the nation. Yet he does not resent being lied to, or repent having helped in the lies. He thinks the good things that came of Nixon’s deviousness compensate for all the bad, and quotes the Master as telling him: “We never could have brought off the opening to China if we hadn’t lied a little, could we?”

Price was supposed to be one of those who brought out the good Nixon—the house intellectual (something he tries to vindicate in his book by pseudo-scientific explanations of Nixon as a “left-brain” classicist). When Watergate revelations were breaking, Daniel Patrick Moynihan fatuously wrote from India that “strong and moral men of the present administration” like Raymond Price would assure the team’s integrity. Yet Price still clings to Nixon, equivocating and excusing—helping him prepare each slither of the Frost interviews. Corruptio optimi pessima. Those who believed in the good Nixon all ended up serving the bad Nixon.

It is distressing to see Nixon’s critics acquiring the paranoid vision of politics that he had. We now get a wave of conspiracy theories, working from the cui bono maxim. It would make policemen’s work very easy if that maxim were truly the guiding one: they would automatically send to jail the principal beneficiary of any victim’s insurance policy. The saddest irony is that Nixon and Joe McCarthy used that maxim in their 1950s charges: who benefited when the Democratic administration “lost” China or failed “the captive nations”? Foreign communists benefited. Therefore foreign communists were running the American government. No wonder Haldeman welcomes all such arguments, subsumes them within his omnidirectional hostility. Nixon infects men with distrust, and even those opposed to him contribute to his effect when they become its “carriers.”

Most conspiracy views begin with the fact that the DNC break-in was undermotivated and overbungled—so it must have had some occult purpose that was deliberately sabotaged. But the Dita Beard affair was undermotivated and overbungled. So was the Ellsberg break-in, So were the Kennedy plots. So was the “spying” on public demonstrators at the Statue of Liberty. So were the faked cables on Diem. So, probably, were other things we do not know about. I find Haldeman plausible when he claims that Nixon often called for retaliatory, self-defeating acts that Haldeman quietly ignored. Nixon’s vindictiveness was petty and ill-aimed, and ultimately self-defeating. He was clumsy at everything else, why not at crime?

Years ago I marveled at the way Nixon could boast in Six Crises that he got in a vicious little kick at a rioter in Latin America who was being dragged off by the police. Haldeman claims in his book that Nixon used to boast with similar pride of the way he told the press off in his “last press conference.” He took deep satisfaction in things others would be (or pretend to be) ashamed of. In discussing that Six Crises passage I called Nixon a “late kicker,” one who discharges his resentment fecklessly, in clumsy delayed reactions. Haldeman recounts an incident, from the 1960 campaign in Iowa, that is almost a parable: Vice President Nixon was on a tour that had been poorly planned, so that hours were wasted in driving from town to town.

Nixon seethed with anger. He was riding in an open convertible and Air Force Major Don Hughes, Nixon’s military aide, was in the seat directly in front of Nixon’s. Suddenly—incredibly—Nixon began to kick the back of Hughes’ seat with both feet. And he wouldn’t stop! Thump! Thump! Thump! The seat and the hapless Hughes jolted forward jaggedly as Nixon vented his rage. When the car stopped at a small town in the middle of nowhere, Hughes, white-faced, silently got out of the car and started walking straight ahead, down the road and out of town. He wanted to get as far away as he could from the Vice-President. I believe he would have walked clear across the state if I hadn’t set out after him and apologized for Nixon and finally talked him into rejoining us.

The only feelings Nixon could convey with some authenticity were resentment and self-pity—valuable items in 1968, when the reaction to war and riots and demonstrations led to a repressive mood in the electorate. The voters had their own enemies list that year. We are asked how the system could go so wrong in giving us Nixon. It didn’t go wrong. People got what they wanted. They knew Nixon as well as any candidate has been known, his strength and his weaknesses: but they were in a mood to accept his weaknesses as strengths. A great many of them wanted something even worse—wanted Agnew or wanted Wallace. The nation at first took a self-defeating satisfaction in its choice—just as Nixon did in all his own late kicks, and silly raids, and secret retributions that backfired.

Of course there will always be some mystery around the Watergate events—but not because of labyrinthine plots and conspiracies; not because the “inefficient” bureaucracy suddenly turned marvelously efficient in destroying a president. These events have the darkness of hatred itself, the futility of envy, the nihilism of spite. Alexander Pope knew there could be idiocy on a heroic scale. The Nixon White House has been called Kafkan or Orwellian, but it was not a place where the lone person faced an impersonal system. It was a world of little men using large powers incompetently from a combination of suspicion and panic. It was a place far closer to Pope’s vision, in The Dunciad, of clownish bungling that verges on anarchy, and of anarchy verging on apocalypse, so that darkness covers all. Everyone was skeined in self-covering layers of suspicion about everyone else:

So spins the silk-worm small its slender store,

And labors till it clouds itself all o’er.

[4.254-255]

Even when one of this crew wants to shed light on the complex scurryings in and around the White House—as Haldeman probably does—he can only throw his own darkness:

Of darkness visible so much be lent

As half to show, half veil the deep intent.

[4.3-4]

These were not men familiar with the day. Darkness was their element, and it will cling to what they did forever.

This Issue

April 6, 1978