Under the title of The Age of German Liberation Peter Paret has provided us with an excellent translation of a book by one of the most important modern German historians: Friedrich Meinecke’s Zeitalter der Deutschen Erhebung. This title, however, in both its English and its German versions, is something of a misnomer, since except when he dealt with political ideas Meinecke was not concerned with Germany as a whole, but only with Prussia, the state which supplied the inspiration, the leadership, and the bulk of the fighting forces that freed Germany from the French after the retreat from Moscow in 1812.

Meinecke wrote his work, for the general public and at the request of his publisher, in 1906 to commemorate the centenary of the beginning of the reform movement in Prussia—a movement that was set in train by Napoleon’s conquest and occupation of the country in 1806 and that ultimately contributed in large measure to his overthrow.

The principal architects of the reforms—the civilians Stein, Hardenberg, and Wilhelm von Humboldt, the soldiers Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Clausewitz, and Boyen—were (apart from Hardenberg, whose raffish character and lack of fixed principles usually disqualified him for the role) among the most famous heroes of imperial Germany. Between 1806 and 1813 the French invasion and occupation, and the heavy indemnity they imposed, reduced the Prussian people to a degree of misery without parallel in Western and Central Europe at the time. But these years, nevertheless, ended with a mobilization of resources for war on a scale unequaled anywhere until then, and seemed to contemporary Germans, and to their successors before 1918, to constitute a heroic age, comparable only to that of Frederick the Great, from which it derived much of its inspiration.

In 1906 Meinecke saw things in this light. Though he regretted the reaction that set in after 1815 this did not seem to him to diminish the achievements of the war years. The results of the age of liberation, he admitted, were “unsatisfactory if aims and achievements are compared” but this, he maintained, was a consequence of the reformers’ propensity to quarrel with one another which resulted inevitably from their greatness. “We stressed,” he said,

this cleft and dissonance, not only to reject trivial patriotic legends, but because the peculiar greatness of the reformers is founded in this lack of harmony. It is inspiring to see these demanding and ambitious men attempt not only the possible but also the impossible and soar far above political realities. In their upward flight they did not ask whether they would crash, and thus awake in those who understand them a sense of the infinite which enables us to bear the finite.

After 1918, and still more after 1945, it was difficult to see things in this way, and Meinecke’s whole attitude to history became suspect. The subjects that interested him were the place of great men in history (his first work was a life of Field Marshal von Boyen), the nature and development of political ideas, and what he called the relationship between “state and spirit”—that is between state policy and the thinking of the intelligentsia—which seemed to him one of beneficent harmony in the age of liberation.

To some extent after 1918, but increasingly after 1945, young historians abandoned these preoccupations for ones suggested by Marxist and neo-Marxist thinking. Frederick the Great was dismissed as a capricious despot who ruled in the interest of that class of exploiters the Prussian noble landowners. The Prussian bureaucracy, in which Stein, Hardenberg, and Wilhelm von Humboldt received their training, and without whose intelligent cooperation the reforms would have been impossible, was commonly portrayed as a sinister institution, typifying the boots and doormat relationships characteristic of Germany in general but Prussia in particular. The bureaucrats were accused of exercising a “dictatorship” even more oppressive and more closely identified with the interests of the possessing classes than had been that of the eighteenth-century Hohenzollerns, whose successors they were said to have deprived of their power. Even Baron Stein, the beau ideal of the historians of imperial Germany, is now being deposed from his pedestal. His principal biographer, Gerhard Ritter, described him as being of unimpeachable honesty and courage, and as incorporating “the ideal of the free and honest man who has always appealed to the Germans.” Now he is more commonly seen as a typical landowner from western Germany (his estates were in the Rhineland) with essentially reactionary ideas—as indeed some of his enemies said of him at the time.

Whereas in fact in 1906 the wars of liberation and the reforms that accompanied them seemed a great national achievement, now the emphasis is on the class struggle and on the projected reforms that were never implemented. Typically the one book that since 1945 has been written in English on this subject (the author, Walter Simon, was a German by birth) is entitled The Failure of the Prussian Reform Movement.

Advertisement

In these circumstances it may seem strange that anyone should wish to translate Meinecke’s Zeitalter der Deutschen Erhebung, which is not only over seventy years old but runs strongly against the current of contemporary judgments, of which, in the nature of the case, it cannot provide a refutation. For one-sided and misleading though these judgments sometimes are, Meinecke wrote before the circumstances responsible for them had arisen and he could not therefore produce an answer to them.

At the end of his life, however, it is doubtful how far he would even have wished to do so. For as with a number of other famous German writers, notably Thomas Mann, his thinking went through various phases. The first phase, of which The Age of German Liberation is typical, was one of pride in Germany’s material and intellectual achievements. But the next phase was one of doubt and the last one of despair. After the end of the Second World War, in 1946, Meinecke, then aged eighty-four, published his Deutsche Katastrophe, in which he attempted to analyze the causes of Hitler’s rise to power and of the disasters that followed. These disasters, he concluded, were due in large part to the triumph of German militarism, which he dated from the end of the period of reform. This is not how he had seen things when he wrote The Age of German Liberation and whether at the close of his life he would have consented to its translation into English must remain uncertain. “The radical break with our militaristic past which we must now take upon ourselves,” he wrote in Die Deutsche Katastrophe, “leads us to question what is to become of our whole historical tradition.”

This remains a perplexing question not only for the Germans but also for foreigners who would like to understand German history but are unable to do so in one of its formative periods because they are faced, without the evidence to choose, with two diametrically opposed points of view. The first view asserts that everything was for the best and the second that everything was for the worst between 1740 and 1819.

That some of the seeds of Nazism were sown at this time is beyond dispute. On the other hand, to dismiss the reign of Frederick the Great as one of exploitation and repression, and to concentrate on the failures of the period of reform, is to make the history of Prussia in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries unintelligible; for plainly Prussia’s rise to the position of a first-class military power, its remarkable war effort between 1813 and 1815, and its military and economic expansion afterward, cannot be explained solely in these terms.

The justification for translating Meinecke’s Age of German Liberation is not only that it is the work of a famous scholar, and typical, in the words of Eckart Kehr (one of Meinecke’s critics whom Professor Paret quotes in his introduction), of German “bourgeois” historiography; it is also because it provides the general reader, as does no other study, with a short, clear, and accurate, though oversimplified and idealized, account of the principal reforms and the reasons for them, and of the major political events that led to Prussia’s collapse and resurgence during the Napoleonic wars.

This is not to say, however, that it explains these matters in a way that any modern reader could find satisfactory; for Meinecke was only minimally concerned with their social and economic setting, as was indeed natural at the time he wrote, when to a greater or lesser extent in every country, but particularly in Germany, such subjects were not respectable. To study social questions in imperial Germany was to be labeled a socialist, as Eckart Kehr observed in the course of his criticism of Meinecke from which Professor Paret quotes. Though this attitude no longer exists, the gaps in our knowledge for which it was responsible have still for the greater part not been filled in the periods with which Meinecke was concerned in his Age of German Liberation. These omissions, however, cannot be explained solely by the present difficulty of approaching the subject with even the minimum of sympathy necessary to understand it; they are also due to the fact, as Professor Paret points out, that the study of sociological problems which has long been fashionable in France still does not find much favor in Germany.

Though the French have produced a very large number of monographs on the social and economic circumstances and attitudes of mind of the principal social groups during the ancien régime and the Revolution, and have largely managed to do so without regard to the constricting ideology which until recently has dictated the general judgments on these periods in France, the Germans have not imitated them. Though we now know a great deal about the conditions of life and attitudes of the various categories of French nobles and peasants, and though similar studies have recently been devoted to sections of the bourgeoisie, there is hardly any comparable information for Prussia. Even if Meinecke himself had wanted to revise his book, he would have found few such studies to draw on. The French and Germans, in fact, have written the histories of their respective countries on such different lines that we lack a basis for comparing them during the periods of revolution and reform, although properly documented comparisons would be invaluable to an understanding of each country at this time in which their destinies were intimately connected, and which was crucial to the development of both.

Advertisement

One possible comparison is suggested by Steven L. Kaplan’s recent work on the French grain trade, entitled Bread, Politics and Political Economy in the Reign of Louis XV. Admittedly this is not written as a Frenchman would have written it, though its inspiration is plainly French. Nor is it an altogether satisfactory account, since Professor Kaplan, as he himself disarmingly admits in his last chapter, is a considerable way from understanding how the French grain trade worked, and his readers in consequence cannot understand this either—a misfortune, it seems, that would at least have been mitigated if Professor Kaplan had realized before he started that the problems which concern him were not peculiar to eighteenth-century France but have arisen in most underdeveloped countries with inadequate means of transport from the beginning of recorded history to the present day.

Much can be learned from twentieth-century experience about the part played by different methods of distribution and control in causing or averting catastrophe in primitive communities when the harvest fails. The Bengal famine of 1942 and 1943, for example, which was responsible for a number of deaths variously estimated at between one and five million, in a population of some forty million, was primarily caused by maldistribution. The failure of the rice harvest, which was the initial cause of the disaster, resulted in a supply of rice that was only 6 percent below normal. In the Middle East at the same time, on the other hand, where similar calamities threatened, they were averted by administrative action taken by the British authorities then occupying the area.

In spite, however, of the complications which Professor Kaplan has introduced into considerable parts of his narrative, because he neglects the general principles which might have helped him to disentangle them, he has a great deal to say elsewhere that is highly illuminating and eloquently expressed. In the first place he stresses the enormous importance in the eighteenth century of the state of the harvest in the French economy, in the calculations of the French government, and in the lives of the population, for most of whom bread was the staple diet and the principal item of expenditure. All this has often been said before, but never more cogently.

Professor Kaplan also brings out in a highly illuminating way the results of this state of affairs on contemporary thinking. That the monarch’s first duty was to prevent his subjects from starving was, he shows, an essential item in the ideology of absolutism. This duty, however, was one which the French government only discharged inadequately in the eighteenth century, even though, for reasons that are still a matter of dispute, it managed better than its predecessors had done in the past. Awareness of its failures provided the new school of political economists, founded by François Quesnay and known as the physiocrats, with its inspiration. As the physiocrats saw things, the reason for the recurrent grain shortages, and for France’s economic backwardness in general, lay in the government’s controls—controls which in the case of the grain trade were designed, by means of a body of regulations relating to the sale, purchase, and movement of grain, to prevent the hoarding and speculation which always accompanied a bad harvest. The physiocrats maintained that these controls perpetuated underproduction and maldistribution because they acted as a disincentive to farmers and traders. To Quesnay and his followers the road to plenty lay through free trade and free enterprise—a doctrine which exercised enormous influence at the time even on those who, like Necker, disagreed with much of what the physiocrats said.

In prerevolutionary France it was nevertheless wholly impracticable to free the grain trade from controls, and the various attempts which were made to do this, which always coincided with bad harvests, only increased the shortages and the bread riots, and gave rise to the myth of the so-called pacte de famine—a supposed conspiracy between the government and the grain merchants to raise the price of grain to a level at which the poor could not afford to buy it.

As Professor Kaplan describes things, the French government and the French people were thus caught between Scylla and Charybdis. On the one hand, the old, paternalistic policies were no longer capable of meeting the needs of a population which, even outside the circles of the immediate victims, was less willing than in the past to accept recurrent scarcity as inevitable. But, on the other hand, the new economic philosophy—which ultimately provided a remedy, though at the cost of great suffering during the changeover—ran counter to all the traditions, prejudices, and expectations of the mass of the nation and of many officials and ministers who still believed that it was the monarch’s duty to see that his subjects were supplied with cheap bread.

No one could dispute the justice of this analysis, but one of the conclusions which Professor Kaplan draws from it is questionable; for he believes that the recurrent shortages and the accompanying riots were events for which the government cannot be held responsible, and which were in the nature of things inevitable.

Professor Kaplan has examined a huge number of contemporary documents and secondary works. In his bibliography the latter account for over one thousand titles. There are, however, at least some volumes on his list which he apparently has not opened and which, had he looked at them, might have caused him to think again. These form a part of the Acta Borussica (the great collection of documents, with long prefaces by famous scholars, on Prussian administration in the eighteenth century) and are titled Getreidehandelspolitik or policy in relation to the grain trade. Admittedly this work, of which the first volume was published in 1896 and the fourth and last in 1931, leaves much to be desired. It is, as the title indicates, more concerned with policy than with its execution; the editors express a more or less uncritical adulation of the Hohenzollerns, and some of their conclusions are contradicted by their own evidence.

Even so, however, it is plain that they have a remarkable story to tell; for Frederick the Great, it emerges, aimed at keeping government stocks of grain equivalent to eighteen months’ consumption scattered about the countryside. He himself maintained in 1752 that by means of these stocks he was able to control grain prices, which in France were subject to wide and continual fluctuations. His claim appears to have been largely justified during the last twenty-three years of his reign except in the early 1770s. But even during these years of scarcity he did much better than his neighbors—both the Austrians and the Russians experienced peasant revolts which assumed the dimensions of civil war. He also did much better than the French, who had their guerre des farines—a series of widespread revolts that were a dress rehearsal for the great peasant risings in the spring and summer of 1789.

In Professor Kaplan’s book the numerous passages concerned with grain stocks are unfortunately among the most confused. Neither the government’s policies, nor their results, nor even the distinction between working and reserve stocks, are made clear. At least, however, it emerges that nothing effective was ever done by means of stockpiling to mitigate the spiraling effects of grain shortages.

In general Professor Kaplan leaves his readers with the impression that no long-term policy in relation to the grain trade (or, for that matter, to any other economic issue) was possible in France, among other reasons because no minister responsible for economic affairs remained in power for more than two or three years, if for as many. It also seems plain that the government was singularly ill-equipped to enforce its orders in the countryside and that, in any case, it could not collect the information that was the precondition of effective action. Why, Frederick the Great asked in 1768, is it never known in France when the export of grain is beneficial and when it is harmful? He concluded that the reason was that the French government lacked in relation to France the knowledge, which he maintained he himself possessed for his own dominions, of how much was consumed and produced in every province every year.

Frederick’s judgment is doubtless open to question. Like all successful men he exaggerated his achievements, as did the historians in the nineteenth century who glorified his reign and overlooked many of its sinister features. Nevertheless it seems obvious that his foreign and domestic policies could not have succeeded or inspired future generations as they did if his administration had been as corrupt, disorderly, and ill-organized as the French.

This is, however, only an a priori judgment, since it is not the achievements but the vices of the German bureaucracy that in the last twenty years or so have been an object of study, and no comprehensive account of its French counterpart has even been written.

The reader must conclude from Professor Kaplan’s work that there was no way out from economic backwardness in France except through revolution, but his account ends with the death of Louis XV and this is not a question which he directly considers. Things took a different course in Prussia, but we still cannot explain in any satisfactory way how the Prussian autocracy, more brutal, more oppressive, and in many ways less enlightened than the French, could not only create, and after 1806 reconstitute, its enormous and efficient army and the economic base on which it depended, but could also build up a consensus strong enough to withstand the collapse of 1806, the revolution of 1848, and the transition from a controlled to a free-enterprise economy.

This crucial transition was one which the French autocracy was incapable of making for reasons of which Professor Kaplan gives us a good idea. It was begun in Prussia in the age of liberation, but neither its significance nor how it was possible emerges from Meinecke’s account.

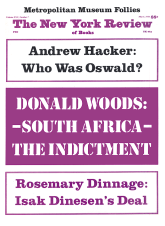

This Issue

May 4, 1978