Right at the outset, no doubt strategically, Jane Howard risks our resistance, by her tone assigning us to the category of the erring, which few of us can like, but which is the category we must agree to if this book is to help us.

They’re saying that families are dying, and soon. They’re saying it loud, but we’ll see that they’re wrong. Families aren’t dying. The trouble we take to arrange ourselves in some semblance or other of families is one of the most imperishable habits of the human race. What families are doing, in flamboyant and dumfounding ways, is changing their size and their shape and their purpose.

Whether or not we’ve been listening to “them,” whoever they are, few of us, encased in families as we mostly are, can have believed that families are on the way out; nor would we even agree that families are changing their shapes. For every arrangement she describes, in this long compendium of anecdotes about today’s families, it’s easy to find a parallel in the literature or history of previous centuries. Think of the domestic arrangements of Fagan, or Mr. Quiverful, or Madame de Vionnet. Think of the Oncida colony or the Knights of Malta. Single-parent families are practically the rule in Jane Austen—are there any “nuclear” families in Dickens? Right away we are on our guard with Ms. Howard.

What manner of book is this? Can it be that families are only the occasion, not the real subject of it? It is not a work of sociology, or psychology, or of dramatic art; perhaps it belongs to a more enduring genre, whose real text is the mind of the writer. It seems to be a series of meditations on truth and behavior, with exempla.

Whatever it is. Howard disarmingly puts the torch to some of the straw in her original statement, by observing that the word family itself is relatively recent, and that the idea of the “conventional nuclear family,” from which she says 83.7 percent of Americans depart, is only the invention of sociologists. She goes after historians, anthropologists, and sociologists with a kind of know-nothing gusto that most people will approve. We know she hardly misrepresents the “helping professions” who “wear celluloid badges at three-day seminars in high-rise motels” and talk about Affines, Surrogates. Male Role Models, Major Intimates, Significant Others, Multilateral Facilitational Relationships. Normalive Data, Coping Mechanisms, Socialixatory Functions, Lower-Class Value Stretch, Shared Meals as a Core Experience, and Family Strength Acknowledgment Experiences. She may be a bit hard on those sociologists and anthropologists who are serious and do have a few reliable descriptive techniques or helpful intuitions for telling us something about the American family, but she’s on pretty safe ground.

Of course, it may appear to the reader that Howard is herself a little tarred with the same brush—she admits to attending panels on “progressive nucleation”—and that what we have here is partly a work of translation of the simpler assumptions of the helping professions into plain jargon-free English, as though she were translating Psychology Today for Family Circle (a not unwelcome stylistic improvement); as when she explains that “exchange theory” means “if you take care of my dog when I’m away, then I’ll owe you a favor.”

But the aims of the book go beyond mere translation. Howard knows that the complicated subject of families cludes reduction to either statistic or slogan. Families are abiding, various, mysterious, indefinable, maybe indescribable, but in an effort to discover what kind of things make families work, describing them is the first and fundamental step. She goes around talking to members of big Southern cians, ashrums, communes, rich families, black families. Greek families, married people, single people, lots of people. Clearly a gregarious woman, she must have enjoyed these visits and confidences, must have a knack for bringing people out, has a good reporter’s eye for the details of their lives and an ear for what they say, Almost any kind of family, she concludes, can work just fine, and those that do work have certain things in common.

She is wise enough to present people’s own versions of their domestic situations, their own rationalizations and opinions, and she mostly takes their word for things. She seems to have the pleasant idea that if a person believes he is happy, believes that he loves, or hates, his parents or mate, then his perceptions ought to carry some weight. “I wouldn’t trade my dad for no man in the world,” she is told by the son of a man who seems to her a most unsympathetic bigot, and she’s willing to see it his way. Her departure from routine post-Freudian skepticism is almost her only deviation from the most fashionable received attitudes of today, and it is refreshing. Nor does she feel the candid camera’s compulsion to catch the belying tie, the white knuckle.

Advertisement

There is something unquestionably fascinating about the domestic arrangements of others, even though the effect here is a bit like the proverbial dinner at a Chinese restaurant—lots of tasty, bits of this and that, hungry two hours later. Or it is like being in a speeding train, watching people for an instant framed In windows, never finding out what happens to them, or what they mean. All these facts add up to a big argument for fiction, for the artist’s controlling intelligence, for the shorthand powers of image and symbol. Howard can tell us something, but Chekhov can make us understand.

If Families were merely a sketchbook, it would fail despite the high quality of many of its observations and enlivening associations. But the book is made to fit into a different category by the unifying and strangely domineering presence of the author herself, In her conversations with the subjects, and in her relation to the reader. You learn a lot about Jane Howard—her history, her habits and preferences, obscure aspects of her spiritual diet: “These Southern family arias nourished me far more reliably than azalcas or grits.” [Do they eat azalcas in the South?] “The 7:40 A.M. ferry for Patchogue leaves Watch Hill in, five minutes, and it’s clear I won’t be on it. It’s clear I seem to need the sun and brine.” At first this seems nothing more than that fashionable, aggressive mode of self-definition encouraged by encounter groups and transactional psychologies that want you to let it all hang out about the self and its needs; but if you were nourished on the modest, self-effacing strategies of Lamb of Montaigne, you may feel you don’t need this. She seems to be taking advantage of you, like a garrulous companion on a long journey.

Yet you come to see that there is something about the author’s presentation of herself that is vital to the book’s success, and that hers is not mere garrulity but the faintly irritating egotism of saints. For this is of course a manual of conduct, and you must have confidence in her priestly authority. It is of her saintliness, or at least of her rectitude, that the author of a work in the exemplary mode must convince you.

Howard has the saint’s shilling as final spiritual trials in the ordinary transactions of daily life, and to come through them, for instance while visiting friend: “I seldom go to church at all much less on the East Side. I must figh being bigoted about the East Side the way some people are bigoted about French Canadians. Three or four friend of mine live there, friends whose company gladdens my soul, but I usually try to lure them westward rather than visit in their part of town.”

She has the saint’s ability to bless and reassure, as when Doris and Eileen, a lesbian couple, express insecurity about their adequacy as parents, “‘You two are probably far more adequate than a lot of straight couples,’ I say, ‘You have humor, for one thing, which isn’t nearly as commonplace as I wish it were.”‘

Her little lectures to her friends enable us to share her erudition and reflections: “I tell Eileen and Doris of the French historian Amaury de Riencourt, who I once heard say in a speech that polarity leads to vitality, that the drive toward sameness ‘might end up by creating a third gender, a neutral type comparable to the sexless workers among ants and bees.”‘ In this way, painlessly, we are instructed that total atheism is out, the East Side is stuffy, lesbian motherhood is in, humor is encouraged, nobody likes drones, and it’s pompous to say “whom”—in fact we learn a whole lot of fashionable attitudes on every page.

Like a saint, Howard does some things so that we won’t have to do them, for instance drink grasshoppers. She does it while visiting Otto Muller, a former hairdresser turned evangelist, and father of eighteen: “I wouldn’t have expected to sit around watching Johnny Carson and drinking grasshoppers anywhere, much less in a former hairdresser’s house purporting to teach The Nine Steps to the Totality of Being a Christian”‘ (sic). If this attitude seems patronizing from such an avowed celebrator of human nature, it’s because she was momentarily rocked from her pedestal of moral egalitarianism by Otto’s unfashionable attitudes on race and sex. He confides things like, “At a queer bar in Detroit where I went once, during a convention. I thought it was funny to see man necking, but now it makes me sick.”

Advertisement

She gently reproves all forms of Illiberality or squareness, but is particularly disturbed by these middle American forms. She and her sister Ann attend a reunion of their own family in the Midwest. “A man with a magnificent American Gothic look about him stood before a flag and sang a rather long arrangement of the ‘Pledge of Allegiance,’ as we all sat with our right hands on our hearts. Ann and I dared not meet each other’s eyes.”

Be not too countrified, be not too urban either. On a visit to a Southern cousin, “I had hoped that we might swim in the Gulf the afternoon I spent with him and Jenny, but since he and she preferred the pool of his apartment complex, that was where we swam and talked.” The deep Puritanism of the ocean bather; the gently censorious lone—what a terrifying relative Jane Howard is.

When we have learned to find her on the side of the angels in everything, we are ready to accept her teaching, and here are the ten rules for having a good family, each a topic in itself suitable for framing in a magazine article of its

- Good families have a chief, or a heroine, or a founder—someone around whom others cluster…and whose example spurs them on to like feats….

- Good families have a switchboard operator—someone like Lilia Economou or my own mother, who cannot help but keep track of what all the others are up to, who plays Houston Mission Control to everyone else’s Apollo….

Good families are much to all their members, but everything to none….

Good families are hospitable….

Good families deal squarely with direness….

Good families prize their rituals….

Good families are affectionate. This of course is a matter of style….

Good families have a sense of place, which these days is not achieved easily…. [All these rules she expands upon helpfully, as here, where she reminds us that “pillows, small rugs, watercolors can dispel much of the chilling anonymity of a subjet apartment or motel room.” Again, she prevents unfashionable mistakes, would doubtless disapprove of stuffed loys. “The End of the Trail,” and a statue of the Virgin Mary.]

Good families, not just the blood kind, find some way to connect with posterity….

Good families also honor their elders. The wider the age range, the stronger the tribe….

Although people deplore or profess to find peculiar the continued proliferation of self-help books, they should surprise us less today than at other times, for, with science and religion compromised, and art hard to come by, to what can people turn? Self-help books are nothing new, they are nearly the oldest form of literature, Cautionary tales, rules for life, admonitions from saintly models convey the reassuring impression that something can be done. Maybe it can, even. Have you hugged your kid today?

All in all, there’s comfort in Howard’s book for everyone who worries about his family arrangements—that is, for maybe 83.7 percent of us. It’s reassuring to read about people who are weirder than you are, and inspiring to read about people who are better. Jane Howard is good-natured and well meaning, and who could disagree with her overall conclusion: “Given families’ persistence, we might as well think about making them useful and decent.” Why not? It’s simple once you know the rules.

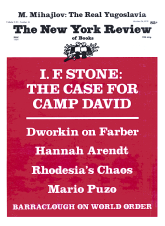

This Issue

October 26, 1978