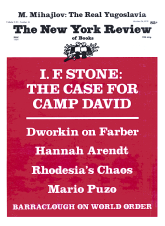

The life of the mind is, under the best of circumstances, a somewhat solitary calling, although, as these posthumous volumes attest, not so solitary as to be an exception to the rule that human things are best nurtured in friendship. Through the efforts of her friends we have the work which Hannah Arendt intended to be her climatic achievement. Mary McCarthy has faithfully attended to the task of editing The Life of the Mind and contributed an affectionate and informative account both of the particular circumstances of its genesis and of the working habits of the author observed over a lifetime of close collaboration. For those readers who have followed Hannah Arendt’s writings and who may have wondered about occasional differences of style and clarity from one to the other, there is a postface by Miss McCarthy that describes in fascinating detail the “Englishing” of Hannah Arendt.

The two volumes carry simple titles, Thinking and Willing. The first volume and part of the second were originally delivered as the Gifford Lectures at the University of Aberdeen. These materials were amplified and finished before her death. Her original plan had called for a third part on “judging” which she considered the crucial element in the overall project. Other than some comments scattered throughout these two volumes, all that we have is a brief but suggestive lecture on the subject that forms an appendix to Willing. Thus, in an important sense, The Life of the Mind is unfinished, but this does not detract from the fascination of these volumes or account for their deficiencies.

The Life of the Mind is characteristically Arendtian, which is to say that there are passages of remarkable insight and suggestiveness, just as there are others that seem wrong-headed and unsupported by fact, text, or reasons. There is a majestic indifference toward the existing literature that surrounds her subject matter. She offered only a slight nod of recognition to the “philosophy of mind,” the Great Totem of Anglo-American philosophers: while Freud, who had some things to say about reason, will, and consciousness, is absolutely taboo. Although these volumes, along with her other writings, deal in some detail with questions of language and speech, there is no evidence of any prior commerce with contemporary linguistics and rhetoric. Although the quest for “meaning” is singled out as the distinctive feature of thinking, a move that might lead one to suppose that she shared certain affinities with contemporary hermeneutics, she chose, instead, not to elect them. Finally, although The Life of the Mind is as much preoccupied by the controversy over the “active” Versus the “contemplative” life as it is over any other single question, it ignores practically all of the major modern writers who have addressed it, writers of the stature of Thomas More, Machiavelli, Bacon, Hobbes, Montesquieu, Marx, and Weber.

It has to be said, also, that the book is strewn with judgments and assertions about the history of Western thought and particular thinkers that are often arbitrary, one-sided, or wrong. Thus she takes as exemplary the ancient Pythagorean description of the philosopher as a spectator who observes but does not participate in the Olympic games, and she uses it to support the ideal of a thinker who mingles with ordinary humanity and participates in a public world. Nothing is said by her about the ancient traditions that depicted the Pythagoreans as a secretive, exclusive society with a very distinct notion about reserving certain esoteric truths for an inner brotherhood. Or, again, she dismisses the Hebraic conception of knowledge as based upon “hearing” rather than “seeing” even though the Old Testament appeals constantly to visual imagery (see, for example, Isaiah 24-25) while the recurrence of prophetic “visions” suggests an emphasis upon seeing that is comparable to that of the ancient Greeks.

Then there is a long discussion of St. Augustine’s concept of “will” that mostly ignores its theological context of sin and salvation. Or her assertion that only among the ancient philosophers can there be found a “record…of what thinking as an activity meant to those who had chosen it as a way of life” (1.12)—as though Descartes, Spinoza, Pascal. Rousseau, and a host of others had not been intensely concerned with precisely that question. Further, although these volumes are concerned with topics which have been disputed for centuries and the approaches are mined with elaborate distinctions, counter-examples, and abandoned conceptions, she disdained even the most elementary precautions in taking up such complex matters.

The Life of the Mind is a collection of loosely related themes, not a sustained inquiry. It includes: the phenomenal nature of “the world”; appearance versus reality; the nature of thinking; the “outer” life and the “inner”: the historical nature of the mind; the loss of intellectual traditions; free will and necessity: the value of contingency and the meaning of freedom; and the temporal location of thinking. With the exception of the discussion of willing, the topics are treated episodically. There are redeeming moments; an admiring portrait of Socrates, for instance, and an acidulous one of Aquinas. But there is no controlling and unifying impulse.

Advertisement

It is, nonetheless, an important work—if one can find the proper terms for understanding it, without glossing over its faults. In that vein, I would suggest, simply, that the value of the Life is inseparable from, even enhanced by, its shortcomings. Its excesses—an outrageous scope, magistral tone, peremptory judgments, and occasional mockery of “professional thinkers”—give its author no place to hide and, consequently, serve to dispel the first impression of the book, namely that it is a large-scale inquiry into the nature and operation of the mind.

She has given us not a life of “the” mind, but something more personal, although not overtly autobiographical. It is a work of self-clarification and retrospection focused upon finding the right terms for the particular form of life of the author and written in awareness of her own mortality. This explains why there is so much of these volumes that will seem familiar to her readers. The same ancient authors and the same striking quotations are all here because they were the influences which had shaped the life of her mind, the stuff on which it had been nurtured. There are some surprises; St. Paul, St. Augustine, and Duns Scotus from earlier centuries, and Kant, Nietzsche, and Heidegger from later times. Yet these are less surprising than they seem at first glance: Augustine, for example, had been the subject of her dissertation, and Scotus had been the centerpiece of the first book published by Heidegger, whose presence haunts the pages of these volumes.

The mention of these figures from the history of Western philosophy is not meant to suggest that they are mere entries in a commonplace book; rather for Arendt they formed moments in her conception of the “history of mind,” reference points for orienting and locating the worth of her own endeavors. She believed that, as a thinking subject, her own history was to be understood not in itself but in its relationship to the larger history of the “Western mind” that had begun with the ancient Greeks and had continued thereafter, undergoing successive crises and metamorphoses, and ending, temporarily, in the crisis of the “present.” The Life of the Mind is a journey that presupposes the Journey which Hegel—with whom she felt compelled to quarrel, though his influence over her was a major one—had memorialized as the Ph ä nomenologie des Geistes.

Hegel’s premise, that Mind has a history, was preliminary to more far-reaching and ultimately political claims, that it was the highest and most decisive form of human history, so that its successive embodiments stand as the revelation of what, at any given historical moment the “real” meaning of the human condition is. In these senses, Mind is not only sovereign, but the main actor in human history. Obviously Geist has virtually nothing in common with the Anglo-American conception of mind as the internal processor of external stimuli or as the busy fabricator and tester of propositions. Geist represents a historical subject, the mind as it undergoes various cultural transformations and vicissitudes over the centuries. Poetry, drama, philosophy, theology, science, history, and art are the successive expressions of the highest achievement of mind in a given epoch; each signifies a different, and limited, understanding of the human spirit, for each institutes a distinct hegemony among the elements of the mind.

The journey is a changing record of the relative position within the mind of experience, imagination, faith, intuition, abstraction, and reason. Mind reflects upon its encounters with the world and comes to acquire greater self-consciousness about its own mediating abilities, including an appreciation of the ironical element in its dialectical advances. For the mind is continually undercutting its own progress by a fertile, almost Machiavellian talent for self-deception. It seemed to be destined for homelessness until, that is, the appearance of the philosophy of Hegel: like Ulysses, mind had finally come home, weary, a bit battered, but triumphantly fulfilled.

Arendt accepted Hegel’s historicist conception of mind—including its near-absolute neglect of the contribution of the Old Testament—but she rejected the “progressive” outlook in its dialectical method. In effect, she threw Hegel into reverse by rejecting the idea of progress and, instead, proceeding on the assumption that a truer understanding of mind requires us to go backward to its authentic beginnings rather than forward to its specious and costly triumphs. The mind’s past becomes the critic or the mind’s present. This critical function is grounded in the assumption that ancient Greek thought, supplemented by selective adaptations from Augustine and Duns Scotus, occupies a unique and privileged position, somehow unravaged by historicism. There is, us a consequence, an archaic basis to the Arendtian conception of mind, just as there was to her conception of politics.

Advertisement

Most forms of archaicism claim that the “values,” philosophies, religions, or politics of some particular past are not really “dead,” only in need of mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Arendt, however, appeared to want to locate the Life at the historical moment when all of the major traditions of thought were lifeless. “Our situation,” she asserted, is one where God, metaphysics, philosophy, scientific positivism, and authority are dead. “The thread of tradition is broken and…we shall not be able to renew it.” All that remains, apparently, is “a fragmented past.” (1.10-11, 212) This was the preliminary to the most important and explicit statement she ever made concerning her intellectual allegiances:

I have clearly joined the ranks of those who for some time now have been attempting to dismantle metaphysics, and philosophy with all its categories, as we have known them from their beginning in Greece until today. [1.212]

This is, however, a misleading account of what occurs in the Life, as it is most certainly of her previous writings, where she had used the “dead” traditions of ancient philosophy and politics to mount a series of critical attacks upon the modes of thought and politics of the present. She had written about “the public realm,” “the founding of new orders,” the bios theoretikos political “deeds” and political “speech.” The inspiration for these and other core notions in her political vocabulary was explicitly acknowledged to be classical. From Homer, Herodotus, Plain, and Aristotle she distilled a distinctive conception of politics which, in its authentic form, loomed larger than life: heroic, declamatory, disdainful of mere material issues, and critical.1

The present work, far from having denied itself the support of tradition, was written within a sharply defined tradition whose philosophical lineage runs uninterruptedly: Kant-Fichte-Hegel-Nietzsche-Heidegger. Once this is recognized, much of the seeming strangeness of her thinking is dissolved. For example, the lofty status she accorded ancient Greek philosophy simply perpetuated the judgment of Hegel. Nietzsche, and Heidegger, who were the three greatest Hellenizers in the history of post-Renaisance philosophy. But unlike Hegel and Nietzsche, who used their incomparable knowledge of the classics to open up radically new conceptions of mind and of its place in the world, Arendt’s conclusions appear highly equivocal and uncharacteristically hesitant, as well as far more reluctant to break with the past.

Arendt intended to locate the meaning of her life in the specific context of the ancient controversy over the nature and respective merits of two supposedly antithetical modes of life, the life of political action (vita activa) and the life of contemplation (vita contemplativa or, alternatively, “the theoretical life”). At the same time, she rejected the terms in which the contemplative life had been cast. A purist, such as Aristotle, had contended that the true theorist did not waste his time thinking about politics at all, but concentrated upon what was eternal and unchanging. Plato, in contrast, had claimed not only that there were timeless truths about politics, but that philosophers, when rightly educated, wore the ones who should apply them in practice.

Arendt wanted to make room for a life devoted to thinking about and judging political matters, but she insisted it had to be aloof and detached. Yet she denied that those who might lead such a life possessed any special knowledge, as Plato had claimed, or even that their lives were, as Plato, Aristotle, and most of antiquity believed, to be lived in a distinctive (e.g., ascetic) way. Thus she aimed at a conception of the “theoretical life” that rejected both terms: theoretical knowledge about politics and a life dedicated to achieving and/or applying it. Nonetheless, she wanted to defend the claim that the mind had something valuable to say about politics, not because its assertions were philosophically or scientifically true but because of their irreducibly human character. At the same time, she believed that the mind was capable of disinterestedness, not as a quality characteristic of its statements but as a possible element of its activity.

These concerns lay behind the abstruse and seemingly anti-political beginnings of The Life of the Mind. Posted at the start is an epigraph from Heidegger that proclaims the irrelevance, even futility, of thinking to worldly concerns. “Thinking does not bring knowledge,” or “produce usable practical wisdom,” or “endow us directly with the power to act.” And, so as to make the point doubly clear, she added brusquely, “there is no clearer or more radical opposition than that between thinking and doing”(1.71).

The unworldliness attributed to thinking was Arendt’s convoluted way of asserting that there is a moral purity to that activity and insinuating—rather than establishing—its right to be heard. In the introduction she indicates the political inspiration of the volumes by recalling how, during the Eichmann trial, she had been struck by the literal “thoughtlessness” of the accused. Eichmann’s crimes seemed due less to a satanle premeditation than to the “absence of thought.” Thinking requires us to “stop and think.” Its interruptive nature, which necessitates that we break off from what we are doing, led her to believe that thinking might “be among the conditions that make men abstain from evil-doing or even actually ‘condition’ them against it” (1.4,5,).

The conception of mind that was supposed to undergird this position might be summarized as follows. There are “three basic mental activities of the mind,” thinking, willing, and judging. Each is “autonomous” and obeys “the laws inherent” in its activity (I. 69, 70)= Thinking she describes as a silent, unobserved dialogue of the self with the self. It is made possible because of the mind’s unique capacity to withdraw from the world without physically leaving it (I. 193). The nature of its activity depends upon a distinction, purportedly Kantian, between “reason” and “intellect” (Vernunft/Verstand).2 Intellect is the cognitive faculty, equated with “knowing” and with the passionate search for truth that has dominated the West since the days of Descartes, although the antecedents are visible in Aquinas. The kinds of truths for which “intellect” has an abiding passion are those which are “necessary” or “indubitable.”

It is this conception of truth that she finds uncongenial to the life of the mind as well as complicit in the contemporary crisis. Truth, in these forms, is said her to be tyrannical. It “compels” assent and we have no choice but submit (I. 61). Accordingly, thinking “reason” (she uses the two interchangeably) has no truck with truth: domain is different; its modality metaphor, not fact:

The need of reason is not inspired by the quest for truth but by the quest for meaning. And truth and meaning are not the same. (I. 15)

Willing is described as “the spring action” and the “mental organ” par excellence of freedom. The excellence the will is that it can say “no” even the most self-evident and hallowed truths (II. 6, 7, 158). The will as Dun Scotus maintained, “can transcend everything” and it “interrupts all causes chains of motivation that would bind it” (II. 136; I. 213). The will’s urge is act, to choose, and, above all, to begin a new series. Augustine had grasped the “truth” of a kind of natural foundation to the freedom of the will, namely that each individual coming into the world has a new beginning, a fresh instance of freedom (II. 108-110). The will is not in any sense omnipotent; it is confined to the world of mind; and once it begins to act, its freedom ceases(II. 141).

Finally, there is judging, “the most political of man’s mental abilities” (I.192) and clearly the one that represents, at least in part, her conception of the “political life” of the mind. Although the fragmentary remains of a lecture make it impossible to reconstruct her ideas, the starting point seems to me highly unpromising. Judging is said to be a “political” capacity but Arendt removed it from politics, denied it any basis in political experience, and sought its content in aesthetics rather than politics. In order to judge, one surrenders “active involvement” for the role of the “spectator.” The “price” of understanding the “spectacle” is “withdrawal.” although not isolation (I. 92-94). Thus the spectator, in effect, displaces the citizen.

Arendt tried to derive the content of judging from an analysis of Kant’s aesthetics and of the paradox that “taste” can serve as the basis for “public” judgments even though it originates in “private” sensations. This she thought possible because “imagination” and “common sense” contribute, respectively, elements of disinterestedness and a desire to fit in with others that purge taste of its idiosyncratic quality (II. 265-270).

This curiously disconnected conception of mind’s “most political ability” was intended to round out her case for the demystification of the “political” role of the theorist: anyone can be a spectator. Yet echoes of the ancient ideal of the theorist haunt the edges of her formulation, leaving an overall impression of equivocally. Thus she attributes to the “spectator” a function whose importance Plato might well have envied:

…the judgment of the spectator creates the space without which no such [aesthetic] objects could appear at all. The public realm is constituted by the critics and the spectators and not by the actors or makers. [II.262]

Thinking, she writes, “has no political relevance unless special emergencies arise” and then it “ecaxes to be a politically marginal activity.” There follows this remarkable bit of imagery:

When everybody is swept away unthinkingly by what everybody else does and believes in, those who think are drawn out of hiding because their refusal to join in is conspicuous and thereby becomes a kind of action. [I. 192]

Leaving aside the faint aroma of Platonism that trails the above passage, the emphasis upon “emergency” and the suggestion that such moments evoke a kind of hero of the mind are consistent with the dominant tendency in her writings toward the preternatural in politics: totalitarianism, genocide, war crimes, violence, revolution, and civil disobedience were her themes.

There is, however, another kind of politics that is partly visible in the Life, one that is not clearly articulated and yet may have been the ultimate aim of her work. I shall call it the “politics of the mind,” meaning by that, first, a conception of politics that takes place on the terrain of the mind, and, second, a critical attack upon the understanding of mind that dominates contemporary culture. Plato was the first philosopher to think explicitly in terms of a “state” of mind: a rightly ordered soul was like a well-governed polity with the “rule” of the “best” principle (reason) corresponding to government by a philosophically trained ruling elite. The political categories employed by Arendt are the ones she developed in The Human Condition. There she had contrasted authentic political action—which she defined as consisting of “great” deeds and noble speech and as performed for its own sake—with instrumental and bureaucratic activity.

In the Life thinking takes the place of action and it, as we have noted, is described in strongly anti-utilitarian terms: its province is “meaning” and this comprises “all the unanswerable. Questions upon which every civilization is rounded” (I.65). Likewise her comments about the scientific “intellect” in The Life of the Mind parallel the anti-political description of “labor” in The Human Condition. The scientific intellect, too, is instrumental, fabricative, and, above all, obsessed with the kind of “coercive” truths that “compel” the mind to obedience (I, 56-60). And just as labor had once served as her symbol of “unfree” activity because bound to “necessity,” so now she found among scientists and philosophers an ominous predilection for “necessity” rather than for “contingency” which, for her, was the presupposition of freedom (II. 32-33).

Her basic aim, unlike Plato’s, was not to promote the hegemony of mind over the world but to find a refuge for lien a world where thinking had become identified with scientific nationality. The extent of her desperation can be gauged by what she conceded to the scientific hard-liners; that while their enterprise yielded demonstrable, useful results, hers was empty, theoretically as well as practically—content, as Hoboes had put it, with “mere inward delight.”

Her way of finding a place for her idea of “thinking” was to create a conception of “the world” that would serve her version of the politics of mind. In The Human Condition the conception of action had depended upon a “public space” where the drama of action would be out in the open and visible to the spectators. In The Life of the Mind the concept of “the world’s phenomenal nature” serves as the public domain for the Arendtian mind. There is, she asserted, a “common” world which can be “shared” by ordinary human beings whose capacity to share renders them “public” beings. Each of us is born “fit for worldly existence.” How things appear in the public world is how they are; “Being and Appearing coincide…” (I. 20). There is no hidden and ultimate reality behind things or within persons. Human existence resembles a theatrum mundi: each of us is both subject and object, perceiver and perceived. “Nothing and nobody exists in this world whose very being does not presuppose a spectator” (I. 19,20).

Arendt’s commitment to the idea that each of us is a public person is intensified by her contempt for the “inner life.” The low esteem of the latter corresponds to the scorn for the “hidden” quality of “private life” that distinguished The Human Condition. The mysteries of body and soul left her impatient: what is “inside,” quite simply, is our insides, “the functional apparatus of the life process” (I.29). These, she declared, were uninteresting and hence radically different from the diverse appearances we seek to present on the “outside” (I.35). The inner life that so fascinates her contemporaries and has produced new sciences of the soul provoked some wonderfully quirky responses from her:

the passions and emotions of the soul…seem to have the same life sustaining and preserving functions our inner organs, with which they also share the fact that only disorder or abnormality can individualize them…. [Psychoanalysis discovers] no more than the ever changing moods, the ups and downs of our psychic life, and [the] results and discoveries are neither particularly appealing nor very meaningful in themselves. [I.35]

The Life reveals Arendt’s lifelong debts to Nietzsche and Heidegger. It is ironical that an author whose reputation was established by studies of totalitarianism and Nazi war crimes should have been deeply influenced by two writers who, for different reasons and with contrasting plausibility, have been accused of Nazi sympathies, Nietzsche before the fact, Heidegger for more substantial reasons. Although neither writer is usually interpreted to be a political thinker, their ideas, creatively reworked, are evident at both a general and specific level of her political theory.

Virtually the entire range of Nietzsche’s ideas—the rejection of philosophy, the contrast of “slave” with “aristocratic” morality, the critique of scientism and of its preoccupations with certainties, the biting ridicule of bourgeois materialism and of its “tic-toe” ideal of happiness—was concerned to encourage those human actions and ideas that challenged accepted standards and sought to transcend them. He was especially savage toward “mediocrity,” warning that it came disguised us love for the downtrodden and was really the expression of the survival instinct of the “herd.”

Nietzsche’s cult of the exceptional reappeared in Arendt’s exulted notion of action:

…action can only to judged by the criterion of greatness because it is in its nature to break through the commonly accepted and reach into the extraordinary, where whatever is true in common and everyday life no, longer applies, because everything that exists is unique and sul generic.3

There was, too, a Nietzschean edge to her elitist claim that “the political way of life…has never been…the way life for the many” but only for “the best,” or that “abundance and endless consumption were the ideals of poor” and corrupted politics.4 But, the other extreme, Nietzsche’s “herd reappears in her analysis of the “mass” basis of totalitarianism: a herd no longer bovine but mobilized and manipulated by an elite drawn from the gutter. Her most original and stunning use of Neitzsche was her portrayal of the Eichmann phenomenon as “the banality of evil.” It challenged one of the most widely accepted interpretations Nazism as the product of “demonic” urges and perverted minds, so exceptional and grotesque as to exempt ordinary human beings from complicity in the “final solution.” She showed that death camps were also the work of bespectacled clerks, more likely to be worried about their hemorrhoids and in grade promotions than about indulging satanic lusts.

From Heidegger she took the assumption—it was little more than that—the Greek beginnings, especially the beginnings of philosophy in the pre-Socratic were a privileged moment in Western thought, not just a starting point for later “developments” but, literally, a stopping point to which later thought must recur and try to recover something of that naïve instant when mind has understood what preparations were needed for it to become receptive to the presence of Being.5 Heidegger taught, ‘too,’ that the nature of truth was that it lay “concealed” and that its presence was disclosed, not forced in the manner of, say, Bacon’s “rack” for Nature, Arendt worked this idea into a striking account of authentic politics as revelatory; the actor revealing himself to his peers by word and deed. Perhaps, above all, she learned from Heidegger what Nietzsche could never have taught: an attitude of wonder and affection toward the diversifies that appear in everyday life.

The Life never manages to overcome a mood of resignation and it closes on the Augustinian note that “we are doomed to be free by virtue of being born” (II.217). Hannah Arendt seems tacitly to have abandoned her position of a decade ago when she had cast the thinker as a “truth-teller” whose vocational duty was to preserve the “factual truth” against the systematic deceptions practiced by contemporary politicians.6 At the end she seemed to want to exchange truth for meaning, fact for metaphor, truth-telling for disclosing what cannot be proven, and to argue that the freedom of the mind becomes possible when thinking is liberated from the tyranny of truth.

One is templed to attribute this melancholy to a feeling of bereftness induced by her recognition that she had been left stranded by the last turn in Heidegger’s thought. As she demonstrates, Heidegger’s critique of Nietzsche’s “will-to-power”ends in passivity, in a condition where the subject wills not, to will, and, consequently, accepts the lot of powerlessness. But those who have read her writings will remember Hannah Arendt not only as a writer of remarkable insight and intelligence, but one of rare courage who took on the gravest and most dangerous problems of the times. A momentary flush of this memorable past is provided by a phrase she used in these volumes, “man the fighter.” Perhaps this, rather than those “Hellonizing ghosts” that Nietzsche warned against, should be the epitaph to the life of her mind.

This Issue

October 26, 1978

-

1

One of the most thoughtful discussions of Arendt’s political ideas is the essay by George Kateb, “Freedom and Worldliness in the Thought of Hannah Arendt.” Political Theory, Vol. V (May 1977), pp. 141-182. Various aspects of her thinking are considered in a special volume of Social Research, Vol. 44 (Spring 1977), edited by Arlen Mack.

↩ -

2

The usual translation of Verstand is “understanding” (as in Kemp Smith’s standard translation of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason): she held this to be a mistranslation (I. 13-14; and see editor’s comments, II. 245).

↩ -

3

The Human Condition (University of Chicago, 1958), p.205

↩ -

4

On Revolution (Viking, 1965), pp. 279-280, 283, 135. A Paler version of the thesis that whatever is generalized so as to be accessible to the “many” is degraded can be found in Heidegger’s conception of “they” as “leveling” and possibility-denying. See Being and Time, translated by J. Macquarrie and E. Robinson (Harper & Row, 1962). I.6 (194-195), p.239.

↩ -

5

See, for example, his Early Greek Thinking (Harper & Row, 1975); What is Called Thinking (Harper & Row, 1968); An Introduction to Metaphysics (Yale University Press, 1974), Chapters II-III. A general discussion of Heidegger’s classicism can be found in Werner Marx, Heidegger and the Tradition (Northeastern University Press, 1971).

↩ -

6

“Truth and Politics,” Philosophy, Politics and Society, 3rd series, edited by P. Laslett and W.G. Runciman (Barnes and Noble, 1967), PP.104-133.

↩