These three novels have been out for several months now and all have received some attention—in two cases very little. None is a “big” novel, none is by a “name” author (though James McConkey certainly has a following among fellow writers and discerning readers), and none seems destined to make much money. All three concentrate, somewhat unfashionably, upon the intensities of domestic life—upon the struggle of well-intentioned people to draw breath for themselves within its confines, upon the curious repetitions and reversals that occur as one generation flows into the next. All three are good novels, with sufficient intensity of vision and stylistic distinction to warrant another look before they are forgotten in the onrush of new titles this fall.

In James McConkey’s The Tree House Confessions the difficulty of drawing breath is made literal: its protagonist, Peter Warden, suffers sporadically from asthma, which is not only an affliction but a resource—something to “fall back on” as his first marriage begins to collapse within weeks of its consummation. Neurasthenic in other respects, delicately attuned to the feelings of his lonely and dignified mother, Peter at the age of fifty undergoes a visionary experience while he is holding the callused hand of his dying mother—an ecstatic experience of the void that confers a fleeting sense of freedom from all constraints—from grief, from memory, from time, from life itself.

Though blissful, this revelation leads to a breakdown of sorts, causing Peter to detach himself from his work on the rural newspaper that he edits and to withdraw from intimacy with his second wife, Ann, to whom he has been happily married for many years. He finds refuge in a tree house he had built for his son Tommy not long before the boy was killed in Vancouver by a runaway truck. There, in the leafy heights, he meditates upon the implications of his experience, relating it to his earliest awareness of nature, to the lives of his parents, his two marriages, and to his guilt and grief over the loss of Tommy. The novel itself is an extended love letter and explanation to Ann—an episodic recherche du temps perdu that he hopes will enable him to create a bridge between the ecstatic glimpse of ultimate freedom and the need to be in the world, to love his wife “here and now,” to be “real” enough to meet her reality. Peter in short confronts the perennial dilemma of mystics: how to reconcile the transcendent, the silent, the timeless, and the empty with all that is busy, noisy, temporal, and crowded.

There is little plot, no real suspense, few surprises. The major events in the life of Peter and his family are announced early in the novel, which then circles and recircles around them. We learn of his parents’ courtship and their life together on an island in Lake Erie where his father successfully practices viticulture and where Peter is born and spends his childhood. We learn of their banishment from this demi-Eden during the Depression and of his father’s guilt-driven desertion of his wife and son, who are reduced to proud poverty, the wife becoming a maid, the son a yard-boy in the town of Catawba, Ohio. There is a brief, poignant account of Peter’s marriage, while at college, to his high-school sweetheart, Sally, whom he has worshipped, mistakenly, as a “free” spirit but who turns out to be dependent on his love in a way that he finds stifling; unable to endure the closeness, he rejects her physically and drives her into leaving him, unaware that she is already pregnant. Thus Peter repeats, with significant variation, his father’s betrayal of his wife. There are only a few glimpses of Peter’s later life with Ann and with Tommy (the son that Sally bore and then deserted); in a novel which, despite its brevity, gives generally an impression of plenitude, these sections alone seem too skimpy to carry the weight assigned to them.

What is interesting about The Tree House Confessions is the intensity which the few central situations and images gain as Peter returns to them, developing them, extracting new significance, new implications. McConkey’s method is quasi-musical, quasi-Proustian. Early in the novel the mother shows the three-year-old Peter how she can stop the night-time singing of cicadas in a tree—a trick she had learned as a child from her own mother.

She approached the maple, and pressed its bark with her palms. The cicadas fell silent. Then it was my turn to try to control their song, but I could not. She once again made them stop. Barefooted, wearing a filmy white summer dress, she was a bodiless presence; she became, it seemed to my marveling mind, one with the bulk of the tree and with the tiny insects in the highest branches, one with the stars that hung from the branches or winked off and on like Christmas lights deep within the wind-stirred leaves.

The image recurs a number of times—most strikingly at the mother’s death-bed, when she is retreating from Peter, gaining a “terrible detachment,” and again at the very end when he compares her dying renunciation of her own past, of her dead husband and living son, to the stilling of a myriad singing insects with a twitch of her hand; it is this renunciation which in turn enables Peter to soar into the sublime silence that lies beyond all existence. Other images—an old horse with a tube in its throat to allow it to breathe, a glacier in the sunlight glimpsed as Peter and Ann drive back from Vancouver after Tommy’s death, the childish fantasy of a submerged Studebaker and its three occupants at the bottom of Lake Erie, the shimmering point of light at the bottom of the well at a deserted farm—these undergo similar development as Peter recalls them in differing contexts. Though he works mostly through the medium of memory and introspective elaboration, the “I-character” of Peter is also capable of an imaginative leap into a scene where he was not present; his accounts of his parents’ courtship and, especially, of one night of rhapsodic communication between them before he was conceived constitute a tour de force of imaginative reconstruction that serves as this novel’s equivalent (on a much reduced scale) of “Swann in Love.”

Advertisement

I suspect that Wordsworth’s ghost as well as Proust’s hovered in the branches above that tree house. Nature, for the boy Peter, is suffused with a maternal presence into which he longs to merge; the recurrencies of nature speak to him, affect his guilts and terrors as well as his pleasures and dreams. “The night sky drew me up, subsumed or vanquished me, in what was so large there were no apparent limits, no final end other than vacuum, emptiness without even an echo.” He at various times experiences extrabodily states that point the way to the ultimate revelation. Though the physical details of nature are rendered with extraordinary precision and tactility throughout the novel, the major human figures other than the parents curiously (or not so curiously) lack bodily presence; Sally, Ann, and Tommy exist almost as ideas, as abstractions. It is as if the maternal presence—and its extension into the natural world—had drained them of substance. I finished this impressive novel vaguely troubled by what seemed to be a certain psychological—as opposed to a metaphysical—shallowness. McConkey never allows Peter, whom he endows with such powers of introspection, to question the essential beneficence of the maternal figure that blights his sexuality and beckons him toward the blankness of annihilation.

In Stephen Minot’s Ghost Images it is the presence of the father, not the mother, who presides over the crack-up of the forty-nine-year-old protagonist, a radical social historian named Kraft Means. Having been a left-wing activist since the days of Henry Wallace and the Progressive Party, he now feels immobilized in the doldrums of the Seventies. Kraft’s refuge—his equivalent of the tree house—is his summer home, a large, deliberately unrestored house on a deserted strip of the Nova Scotia coast to which he comes, out of season, to escape the healthy tumult of his family and, ostensibly, to finish a critical history of the liberal tradition in America. Instead, he wastes time, talks to himself, daydreams about the past, and conducts an affair with a local girl, Thea McKnight, who lives with her grandfather, an ancient lobsterman, in a boathouse in the tidal marshes. In keeping with his romanticized view of labor, which seems to derive from Ruskin and William Morris, Kraft idealizes both of the McKnights, seeing them as survivors of a nineteenth-century way of life based upon simple needs, hard work, and the use of handcrafted implements—an existence free from the taint of gross consumerism and debilitating “improvements.”

In June, when the novel opens, Kraft’s family arrives, led by his wife Tammy, a competent, energetic woman who has worked at his side in various radical causes ever since she was his student at Yale. Defensive about his failure to make progress on his book, and furtive about Thea, Kraft shrinks from the briskness of Tammy’s presence and from the noisy intrusiveness of his three likable children. Things are made worse by the arrival of two houseguests: his publisher, Harry, and his wife’s absurd sister, Min, who believes in spirits and subscribes to every sort of theosophical nonsense. Pleading the need to work, Kraft spends as much time as he can in his study, where he gives way to a dangerous indulgence: reading his father’s secret journal which Tammy, at his request, has brought along.

Advertisement

The father, a remote and awesome figure who died when Kraft was eleven, is thus introduced as a major character in the novel. Superficially, he is the opposite of Kraft in every way—a rich Bostonian, an aggressive capitalist who builds the family trust into a powerful conglomerate, a man who revels in his privileged status, accepts without guilt the ministrations of numerous servants, and enjoys the “simple life” in an elaborate family compound on the Massachusetts coast. The juxtaposing of father and son is handled with skill and psychological acuity by Minot, who keeps the course of action in the present pointing strongly in the direction of ultimate violence as the irruption of the past becomes more and more insistent. In between family excursions, picnics, fishing trips, rancorous conversations, and increasingly drunken behavior on his own part, Kraft sneaks off like a guilty voyeur to read about his widowed father’s growing involvement with the young housekeeper, Miss Winslow, who eventually becomes his second wife and Kraft’s mother. In effective stylistic contrast to the thickly textured account of the Nova Scotian present, the journal entries are laconic. Just enough detail is given to convey the appropriate period flavor:

June 19, Sat., 1926. Moved to Croftham [the family compound] for the summer. Got staff up at 5:00 a.m. to complete packing and sent them down to station with trunks, hampers, and cases in three cabs…. Then Miss W. and I drove to Croftham at breakneck speed, racing the train to unload and hide booze in private. Later met staff at depot as if coming from Boston.

Delivered them to the house in time for a quick sail in a stiff S.W. gale and then a swimming lesson for Miss W. Like almost all from fishing and farming families around here, she has never swum a stroke. Astonishing! Wind dropped at twilight for picnic on beach….

June 20, Sun., 1926. Breakfast late—8:30—on acct. of being Sunday. A pleasure to be at the Cottage again…. Chopped wood in afternoon. Miss W. brought picnic of my favorites—call’s tongue, pickled beets, and bottles of icecold Chablis…. Took Miss W. sailing in late afternoon and in evening had run before roaring fire. Rum still a new and heady experience for Miss W. An extraordinary evening. Most pleased at turn of events.

The father emerges as a lonely, driven, and passionate figure, increasingly sympathetic despite his savagely reactionary views. As his fortune disintegrates during the Depression, he succumbs more and more to gout, rum, and anger—in ways that parallel what is happening to his son. A few months after his death, the family compound is wrecked by the great hurricane of 1938—an event recalled by Kraft in one of the novel’s most powerful set pieces.

Ghost Images is in some respects a rather clumsy performance. The dialogue—particularly the conversations between Kraft and his wife and guests—tends to be stilted and more than a little arch. Kraft’s idealization of Thea as a child of nature is made barely credible; her docile acceptance of the role is not. The upbeat conclusion—with the errant Kraft restored to his senses and to his family—seems gratuitous. Too many themes, too much commentary, too much underlining of already obvious parallels—these betray a somewhat naïve earnestness in Minot’s approach to his material. But Ghost Images, despite unsatisfactory aspects that might well drag down another novel, is, in its pursuit of the father-son story, a strong and compelling work of fiction, one that not only held my interest but stimulated, in the end, considerably more admiration than discontent.

Let the Lion Eat Straw is the first novel by a young woman who has already secured some reputation as a poet. To say that it is very much a poet’s novel may be off-putting to some prospective readers, but that characterization is, I think, accurate; it is not meant to suggest, derogatorily, that the novel lacks a clear line of narrative action but rather that Ellease Southerland is preoccupied more with the sensory impact of language as it proceeds in short bursts—word by word, line by line—than with the creation of broad and rapid effects. To this end, often employing the rhythms and locutions of Black English, she has constructed a kind of linguistic screening device through which the events of her story—events of sometimes complex implication—are made to seem as direct, highly colored, and startling as a painting by an unusually gifted child. Here is a passage in which the six-year-old Abeba, the heroine (not too strong a term) of the novel, is led through the streets of the Brooklyn ghetto on the night of her arrival by bus from North Carolina:

Music. She heard and turned suddenly. Saw boys standing in a circle looking into each other’s eyes singing serious as casts.

Hey-bob-a-ree-bob

She’s my baby.

Hey-bob-a-ree-bob

Don’t mean maybe.They sang it some more, moving their shoulders and heads. Old women with high blood pressure walked by in run-down shoes seemed to know the song. Women carried shopping bags of bad fruit from the markets on Glenmore and Pitkin, bags wet-brown with the juice of rotting fruit. Understood the song. Little girls in badly cut skirts with unwashed skinny legs hopscotched on the sidewalk, kicking soda-pop tops.

The story moves with linear simplicity, depicting episodes in the life of Abeba from her early childhood to her death at the age of forty-five. Illegitimate, cared for during infancy by an aged midwife, Abeba is brought to New York by her mother, Angela, a harsh and disapproving woman, a fervent church-goer. The child shows exceptional musical ability, which is encouraged by her kindly stepfather. It is this ability—and the constricted outlets that it finds under the pressures of extreme poverty, early marriage to a lay-preacher, hard work, and the bearing and rearing of fifteen children—that provides one major theme of the novel. Another is Christianity—black, Protestant Christianity with its hymns, sermons, church dinners, and triumphant Easters—as it molds and sustains the lives of this “backlog of blacks from the back load of Southern buses.” A third is the endless struggle for a good life under conditions that have driven thousands into the aimless and destructive life of the streets. Abeba is sexually abused by her natural uncle when she is fifteen. Her preacher-baker-caterer husband Daniel, a deep-voiced and usually loving man, suffers occasional bouts of madness, during one of which he nearly kills his children. The physical environment is often appalling:

“Can’t have bakery here,” Angela said. “Rats eat the bread. Rats in Brownsville big as the cats.”

They were terrible rats. Walked off with bacon and sweet candy tied to small traps. Daniel had to get rat-sized traps strong enough to snap a small child’s hand. Abeba stuffed cardboard at the base of cribs so rats wouldn’t jump through the slats and bite her babies. Attracted to the sweet smell of babies’ urine. She sensed them waiting in the dark. Heard them on the night floor. Her nerves a net triggered when they set foot near the crib.

Daniel stuffed rags into cracks beneath the bakery door.

This struggle is recorded with a singular lack of bitterness. Small but soul-stirring achievements, moments of happiness and domestic warmth, an eager involvement with the sheer dailiness of existence—these set the dominant key of the novel. A black militant might well be infuriated by it. And indeed Let the Lion Eat Straw too often slides into sentimentality, becoming rhapsodic and falsely naïve. The concern with African history and the bestowal of African names—not only on Abeba (born, presumably, in the late 1920s) but also on a number of her children—seems anachronistic. Perhaps too many undertones, too many ambiguities have been sacrificed for the sake of the bright primary colors that the author prefers.

But, weaknesses and excesses apart, I think that Ellease Southerland’s decision to work with a restricted palette (so to speak) was correct. The complexities, psychological and sociological, are not so much ignored as filtered out. What remains—the celebration of a difficult life well lived—becomes moving in the very simplicity of its contours, in the immediacy with which the reader’s senses are involved in the broken rhythms and in the exceptional concreteness of the images. I will conclude with this brief episode from Daniel’s courtship of Abeba:

“I stopped by, hoped you would go over this solo for me?” He carried his music rolled tight.

“Sure.”

She sat.

He stood near. Unbuttoned his shirt cuffs. Folded back neatly to the elbow. Opened top button. His face and neck smooth black against blue shirt.

“I’m a little fellow,” he said, “but got a big neck. Make those high notes and button pop straight off.” He looked at her. “Whenever you’re ready.”

She nodded.

He sang.

Many brave souls are asleep in the deep.

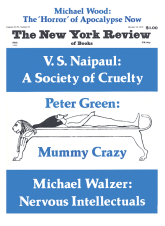

This Issue

October 11, 1979