Hunger is, to describe it most simply, an urgent need for food. It is a craving, a desire. It is, I would guess, much older than man as we now think of him, and probably synonymous with the beginnings of sex. It is strange that we feel that anything as intrinsic as this must continually be wooed and excited, as if it were an unwilling and capricious part of us. If someone is not hungry, it indicates that his body does not, for a time and a reason, want to be fed. The logical thing, then, is to let him rest. He will either die, which he may have been meant to do, or he will once more feel the craving, the desire, the urgency to eat. He will have to do that before he can satisfy most of his other needs. Then he will revive again, which apparently he was meant to do.

It is hard to understand why this instinct to eat must be importuned, since it is so strong in all relatively healthy bodies. But in our present Western world, we face a literal bombardment of cajolery from all the media to eat this or that. It is as if we had been born without appetite, and must be led gently into an introduction to oral satisfaction and its increasingly dubious results, the way nubile maidens in past centuries were prepared for marriage proposals and then their legitimate defloration.

The language that is developing, in this game of making us want to eat, is far from subtle. To begin with, we must be made to feel that we really find the whole atavistic process difficult, or embarrassing or boring. We must be coaxed and cajoled to crave one advertised product rather than another, one taste, on presentation of something that we might have chosen anyway if let alone.

The truth is that we are born hungry and in our own ways will die so. But modern food advertising assumes that we are by nature bewildered and listless. As a matter of fact, we come into the world howling for Mother’s Milk. We leave it, given a reasonable length of time, satisfied with much the same bland if lusty precursor of “pap and pabulum,” tempered perhaps with a brush of wine on our lips to ease the parting of body and spirit. And in between, today, now, we are assaulted with the most insulting distortion of our sensory linguistics that I can imagine. We are treated like innocents and idiots by the advertisers, here in America and in Western Europe. (These are the only two regions I know, even slightly, but I feel sure that this same attack on our innate common sense is going on in the Orient, in India, in Brazil….)

We are told, on radio and television and in widely distributed publications, not only how but what to eat, and when, and where. The pictures are colorful. The prose, often written by famous people, is deliberately persuasive, if often supercilious in a way that makes us out as clumsy louts, gastronomical oafs badly in need of guidance toward the satisfaction of appetites we are unaware of. And by now, with this constant attack on innate desires, an attack that can be either overt or subliminal, we apparently feel fogged-out, bombed, bewildered about whether we really crave some peanut butter on crackers as a post-amour snack, or want to sleep forever. And first, before varied forms of physical dalliance, should we share with our partner a French aperitif that keeps telling us to, or should we lead up to our accomplishments by sipping a tiny glass of Sicilian love potion?

The language for this liquid aphro-cut is familiar to most of us, thanks to lush ads in all the media. It becomes even stronger as we go into solid foods. Sexually the ads are aimed at two main groups—the Doers and the Dones. Either the reader/viewer/listener is out to woo a lover, or has married and acquired at least two children and needs help to keep the machismo-level high. Either way, one person is supposed to feed another so as to get the partner into bed and then, if possible, to pay domestic maintenance—that is, foot the bills.

One full-page color ad, for instance, shows six shots of repellently mingled vegetables, and claims boldly that these combinations “will do almost anything to get a husband’s attentions.” They will “catch his passing fancy…on the first vegetables he might even notice.” In short, the ad goes on with skilled persuasion, “they’re vegetables your husband can’t ignore.” This almost promises that he may not ignore the cook either, a heartening if vaguely lewd thought if the pictures in the ad are any intimation of his tastes.

Advertisement

It is plain that if a man must be kept satisfied at table, so must his progeny, and advertisers know how to woo mothers as well as plain sexual companions. Most of their nutritional bids imply somewhat unruly family life, that only food can ease: “No more fights over who gets what,” one ad proposes, as it suggests buying not one but three different types of frozen but “crisp hot fried chicken at a price that take-out can’t beat”: thighs and drumsticks, breast portions and wings, all coated with the same oven-crunchy-golden skin, and fresh from freezer to stove in minutes. In the last quarter of this family ad there is a garishly bright new proposal, the “no-fire, sure-fire, barbecuesauced” chicken. Personal experience frowns on this daring departure from the national “finger-lickin” syndrome: with children who fight over who gets what, it would be very messy.

It is easy to continue such ever-loving family-style meals, as suggested by current advertising, all in deceptively alluring color in almost any home-oriented magazine one finds. How about enjoying a “good family western,” whatever that may be, by serving a mixture of “redy-rice” and leftover chicken topped with a blenderized sauce of ripe avocado? This is called “love food from California,” and it will make us “taste how the West was won.” The avocado, the ad goes on, will “open new frontiers of wholesome family enjoyment.” And of course the pre-spiced-already-seasoned “instant” rice, combined with cooked chicken, will look yummy packed into the hollowed fruit shells and covered with nutlike green stuff. All this will help greatly to keep the kids from hitting each other about who gets what.

The way to a man’s heart is through his stomach, we have been assured for a couple of centuries, and for much longer than that good wives as well as noted courtesans have given their time and thought to keeping the male belly full (and the male liver equally if innocently enlarged). By now this precarious mixture of sex and gastronomy has come out of the pantry, so to speak, and ordinary cookbook shelves show Cuisine d’amour and Venus in the Kitchen alongside Mrs. Rombauer and Julia Child.

In order to become a classic, which I consider the last two to be, any creation, from a potato soufflé to a marble bust or a skyscraper, must be honest, and that is why most cooks, as well as their methods, are never known. It is also why dishonesty in the kitchen is driving us so fast and successfully to the world of convenience foods and franchised eateries.

If we look at a few of the so-called cookbooks now providing a kind of armchair gastronomy (to read while we wait for the wife and kids to get ready to pile in the car for supper at the nearest drive-in), we understand without either amazement or active nausea some such “homemade” treat as I was brought lately by a generous neighbor. The recipe she proudly passed along to me, as if it were her great-grandmother’s secret way to many a heart, was from a best-selling new cookbook, and it included a large package of sweet chocolate bits, a box of “Butter Fudge” chocolate cake mix, a package of instant vanilla pudding, and a cup of imitation mayonnaise. It was to be served with synthetic whipped cream sprayed from an aerosol can. It was called Old-Fashion Fudge Torte.

This distortion of values, this insidious numbing of what we once knew without question as either True or False, can be blamed, in part anyway, on the language we hear and read every day and night about the satisfying of such a basic need as hunger. Advertising, especially in magazines and books devoted to such animal satisfaction, twists us deftly into acceptance of the new lingo of gastronomical seduction.

A good example: an impossibly juicy-looking pork chop lies like a Matisse odalisque in an open microwave oven, cooked until “fall-from-the-bone-tender.” This is a new word. It still says that the meat is so overcooked that it will fall off its bone (a dubious virtue!), but it is supposed to beguile the reader into thinking that he or she (1) speaks a special streamlined language, and (2) deserves to buy an oven to match, and (3) appreciates all such finer things in life. It takes know-how, the ad assures us subliminally, to understand all that “fall-from-the-bone-tender” really means!

This strange need to turn plain descriptive English into hyphenated hyperbole can be found even in the best gastronomical reviews and articles as well as magazine copy. How about “fresh-from-the-oven apple cobbler,” as described by one of the more reputable food writers of today? What would be wrong, especially for someone who actually knows syntax and grammar, in saying “apple cobbler, fresh from the oven”? A contemporary answer is that the multiple adjective is more…uh…contemporary. This implies that it should reach the conditioned brain cells of today’s reader in a more understandable, coherent way—or does it?

Advertisement

The vocabulary of our kitchen comes from every part of the planet, sooner or later, because as we live, so we speak. After the Norman Conquest in 1066, England learned countless French nouns and verbs that are now part of both British and American cooking language: appetite, dinner, salmon, sausage, lemon, fig, almond, and so on. We all say roast, fry, boil, and we make sauces and put them in bowls or on plates. And the German kitchen, the Aztecan: they too gave us words like cookie and chocolate. We say borscht easily (Russian before it was Yiddish). From slave-time Africa there is the word gumbo, for okra, and in benne biscuits there is the black man’s sesame. Some people say that alcohol came from the nonalcoholic Arabs.

But what about the new culinary language of the media, the kind we now hear and view and read? What can “freezer-fresh” mean? Fresh used to imply new, pure, lively. Now it means, at best, that when a food was packaged, it would qualify as ready to be eaten: “oven-fresh” cookies a year on the shelf, “farm-fresh” eggs laid last spring, “corn-on-the-cob fresh” dehydrated vegetable soup-mix….

Personal feelings and opinions and prejudices (sometimes called skunners) have a lot to do with our reactions to gastronomical words, and other kinds. I know a man who finally divorced his wife because, even by indirection, he could not cure her of “calling up.” She called up people, and to her it meant that she used the telephone—that is, she was not calling across a garden or over a fence, but was calling up when she could not see her friends. Calling and calling up are entirely different, she and a lot of interested amateur semanticists told her husband. He refused to admit this. “Why not simply telephone them? To telephone you don’t say telephone up,” he would say. Her phrase continued to set his inner teeth, the ones rooted directly in his spiritual jaw, on such an edge that he finally fled. She called up to tell me.

This domestic calamity made me aware, over many years but never with such anguish, how up can dangle in our language. And experience has shown me that if a word starts dangling, it is an easy mark for the careless users and the overt rapists of syntax and meaning who write copy for mass-media outlets connected, for instance, with hunger, and its current quasi satisfactions. Sometimes the grammatical approach is fairly conventional and old-fashioned, and the up is tacked onto a verb in a fairly comprehensible way. “Perk up your dinner,” one magazine headline begs us, with vaguely disgusting suggestions about how to do it. “Brighten up a burger,” a full-page lesson in salad-making with an instant powder tells us. (This ad sneaks in another call on home unity with its “unusually delicious…bright…tasty” offering: “Sit back and listen to the cheers,” it says. “Your family will give them to this tasty-zesty easy-to-make salad!”)

Of course up gets into the adjectives as well as the verbs: souped up chicken and souped up dip are modish in advertising for canned pudding-like concoctions that fall in their original shapes from tim to saucepan or mixing bowl, to be blended with liquids to make fairly edible “soups,” or to serve in prefab sauces as handy vehicles for clams or peanuts or whatever is added to the can-shaped glob to tantalize drinkers to want one more Bloody Mary. They dip up the mixture on specially stiffened packaged “chips” made of imitation tortillas or even imitation reconditioned potatoes, guaranteed not to crumble, shatter, or otherwise mess up the landscape….

Verbs are more fun than adjectives, in this game of upmanship. And one of the best/worst of them is creeping into our vocabularies in a thoroughly unsubtle way. It is to gourmet up. By now the word gourmet has been so distorted, and so overloaded, that to people who know its real meaning it is meaningless. They have never misused it and they refuse to now. To them a gourmet is a person, and perforce the word is a noun. Probably it turned irrevocably into an adjective with descriptive terms like gourmet-style and gourmet-type. I am not sure. But it has come to mean fancy rather than fastidious. It means expensive, or exotic, or pseudo-elegant and classy and pricey. It rarely describes enjoyment. It describes a style, at best, and at worst a cheap imitation of once-stylish and always costly affectation.

There is gourmet food. There are gourmet restaurants, or gourmet-style eating places. There are packaged frozen cubes of comestibles called gourmet that cost three times as much as plain fast foods because, the cunningly succulent mouth-watering ads propose, their sauces are made by world-famous chefs, whose magical blends of spices and herbs have been touched off by a personalized fillip of rare old Madeira. In other words, at triple the price, they are worth it because they have been gourmeted up. Not long ago I heard a young woman in a supermarket say to a friend who looked almost as gaunt and harried as she, “Oh god…why am I here? You ask! Harry calls to say his sales manager is coming to dinner, and I’ve got to gourmet up the pot roast!”

I slow my trundle down the pushcart aisle.

“I could slice some olives into it, maybe? Pitted. Or maybe dump in a can of mushrooms. Sliced. It’s got to be more expensive.”

The friend says, “A cup of wine? Red. Or sour cream…a kind of Stroganoff…?”

I worm my way past them, feeling vaguely worried. I long to tell them something—perhaps not to worry.

There are, of course, even more personal language shocks than the one that drove a man to leave his dear girl because she had to call people up. Each of us has his own, actively or dimly connected with hunger (which only an adamant Freudian could call his!). It becomes a real embarrassment, for example, when a friend or a responsible critic of cookbooks or restaurants uses words like yummy, or scrumptious. There is no dignity in such infantile evasions of plain words like good—or even delicious or excellent.

My own word aversion is longstanding, and several decades from the first time I heard it I still pull back, like the flanges of a freshly opened oyster. It is the verb to drool, when applied to written prose, and especially to anything I myself have written. Very nice people have told me, for a long time now, that some things they have read of mine, in books or magazines, have made them drool. I know they mean to compliment me. They are saying that my use of words makes them oversalivate, like hapless dogs waiting for a bell to say “Meat!” to them. It has made them more alive than they were, more active. They are grateful to me, perhaps, for being reminded that they are still functioning, still aware of some of their hungers.

I too should be grateful, and even humble, that I have reminded people of what fun it is, vicariously or not, to eat/live. Instead I am revolted. I see a slavering slobbering maw. It dribbles helplessly, in a Pavlovian response. It drools. And drooling, not over a meaty bone or a warm bowl of slops, is what some people have done over my printed words. This has long worried me. I feel grateful but repelled. They are nice people, and I like them and I like dogs, but dogs must drool when they are excited by the prospect of the satisfaction of alerted tastebuds, and two-legged people do not need to, and in general I know that my reaction to the fact that some people slobber like conditioned animals is a personal skunner, and that I should accept it as such instead of meeting it like a stiff-upper-lipped Anglo-Saxon (and conditioned!) nanny.

I continue, however, to be regretfully disgusted by the word drool in connection with all writing about food, including my own. And a few fans loyal enough to resist being hurt by this statement may possibly call me up.

It is too easy to be malicious, but certainly the self-styled food experts of our current media sometimes seem overtly silly enough to be fair game. For anyone with half an ear for the English-American language we write and speak, it is almost impossible not to chuckle over the unending flow of insults to our syntax and grammar, not to mention our several levels of intelligence.

How are we supposed to react to descriptive phrases like “crisply crunchy, to snap in your mouth”? We know this was written, and for pay, by one or another of the country’s best gastronomical hacks. We should not titter. He is a good fellow. Why then does he permit himself to say that some corn on the cob is so tender that “it dribbles milk down your chin”? He seems, whether or not he means well, to lose a little of the innate dignity that we want from our gourmet-judges. He is like a comedian who with one extra grimace becomes coarse instead of funny, or like an otherwise sensitive reader who says that certain writing makes him drool.

Not all our food critics, of course, are as aware of language as the well-known culinary experts who sign magazine articles and syndicated columns. And for one of them, there are a hundred struggling copywriters who care less about mouth-watering prose than about filling ad space with folksy propaganda for “kwik” puddings and suchlike. They say shamelessly, to keep their jobs, that Mom has just told them how to make instant homemade gravy taste “like I could never make before!” “Believe me,” they beg, “those other gravies just aren’t the same! This has a real homemade flavor and a rich brown color. Just add it to your pot drippings.” And so on.

Often these unsung kitchen psalmists turn, with probable desperation, to puns and other word games. They write, for instance, that frozen batter-fried fish are so delicious that “one crunch and you’re hooked!” Oh, hohoho ha ha. And these same miserable slaves produce millions of words, if they are fortunate enough to find and keep their jobs, about things like synthetic dough that is “pre-formed” into “oldfashioned shapes that taste cooky-fresh and crunchy” in just fifteen minutes from freezer to oven to the kiddies’ eager paws and maws.

When the hacks have proved that they can sling such culinary lingo, they are promoted to a special division that deals even more directly with oral satisfaction. They write full-page ads in juicy color, about cocktail nibbles with “a fried-chicken taste that’s lip-lickin’ good.” This, not too indirectly, is aimed to appeal to hungry readers familiar with a franchised fried chicken that is of course known worldwide as finger-lickin good, and even packaged Kitty Krums that are whisker-lickin good. (It is interesting and reassuring, although we must drop a few g’s to understand it, that modern gastronomy still encourages us to indulge in public tongueplay.)

Prose by the copywriters usually stays coy, but is somewhat more serious about pet foods than humanoid provender. Perhaps it is assumed that most people who buy kibbles do not bother to read the printed information on all four sides of their sacks, but simply pour the formula into bowls on the floor and hope for the best. Or perhaps animal-food companies recognize that some of their slaves are incurably dedicated to correct word usage. Often the script on a bag of dry pet food is better written than most paperback novels. Possibly some renegade English instructor has been allowed to explain “Why Your Cat Will Enjoy This.” He is permitted tiny professorial jokes, now and then: “As Nutritious As It Is Delicious,” one caption says, and another section is called “Some Reading on Feeding,” and then the prose goes all out, almost euphorically, with “Some Raving on Saving.” The lost academician does have to toss in a few words like munchy to keep his job, but in general there is an enjoyably relaxed air about the unread prose on pet-food packages, as opposed to the stressful cuteness of most fashionable critics of our dining habits.

Of course the important thing is to stay abreast of the lingo, it seems. Stylish restaurants go through their phases, with beef Wellington and chocolate mousse high in favor one year and strictly for Oskahoola, Tennessee, the next. We need private dining-out guides as well as smart monthly magazines to tell us what we are eating tonight, as well as what we are paying for it.

A lot of our most modish edibles are dictated by their scarcity, as always in the long history of gastronomy. In 1978, for instance, it became de rigueur in California to serve caviar in some guise, usually with baked or boiled potatoes, because shipments from Iran grew almost as limited as they had long been from Russia. (Chilled caviar, regal fare, was paired with the quaintly plebeian potato many years ago, in Switzerland I think, but by 1978 its extravagant whimsy had reached Hollywood and the upper West Coast by way of New York, so that desperate hostesses were buying and even trying to “homemake” caviar from the Sacramento River sturgeons. Results: usually lamentable, but well meant.)

All this shifting of gustatory snobbism should probably have more influence on our language than it does. Writers for both elegant magazines and “in” guides use much the same word-appeal as do the copywriters for popular brands of convenience foods. They may not say “lip-smackin” or “de-lish,” but they manage to imply what their words will make readers do. They use their own posh patter, which like the humbler variety seldom bears any kind of scrutiny, whether for original meaning or plain syntax.

How about “unbelievably succulent luscious scallops which boast a nectar-of-the-sea freshness”? Or “a beurre blanc, that ethereally light, grandmotherly sauce”? Or “an onion soup, baked naturellement, melting its kneedeep crust of cheese and croutons”? Dressings are “teasingly-tart,” not teasing or tart or even teasingly tart. They have “breathtakingly visual appeal,” instead of looking yummy, and some of them, perhaps fortunately, are “almost too beautiful to describe,” “framed in a picture-perfect garnish of utter perfection and exquisiteness,” “a pinnacle of gastronomical delight.” (Any of these experiences can be found, credit card on the ready, in the bistros-of-the-moment.)

It is somewhat hard to keep one’s balance, caught between the three stools of folksy lure, stylish gushing, and a dictionary of word usage. How does one parse, as my grandfather would say, a complete sentence like “The very pinkness it was, of mini-slices”? Or “A richly eggy and spiritous Zabaglione, edged in its serving dish with tiny dots of grenadine”? These are not sentences, at least to my grandfather and to me, and I think spirituous is a better word in this setting, and I wonder whether the dots of grenadine were wee drops of the sweet syrup made from pomegranates or the glowing seeds of the fruit itself, and how and why anyone would preserve them for a chic restaurant. And were those pink mini-slices from a lamb, a calf? Then there are always verbs to ponder on, in such seductive reports on what and where to dine. One soup “packs chunks” of something or other, to prove its masculine heartiness in a stylish lunchtime brasserie. “Don’t forget to special-order!” Is this a verb, a split infinitive, an attempt of the reporter to sound down-to-earth?

Plainly it is as easy to carp, criticize, even dismiss such unworthy verbiage as it is to quibble and shudder about what the other media dictate, that we may subsist. And we continue to carp, criticize, dismiss—and to eat, not always as we are told to, and not always well, either! But we were born hungry.

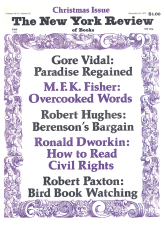

This Issue

December 20, 1979