In the flurry created by Antonia Fraser’s King Charles II Richard Ollard’s book is likely, undeservedly, to be overlooked. Also it is an odd book—a long essay, attached to a simple narrative structure, or rather chronology, since there is no story in a strict sense of the word. Salient facts are mentioned—the fiasco of the Spanish marriage negotiations of Charles I’s youth, the Civil War, the Execution, the Restoration, the Dutch in the Medway—episodes which are connected by little or no narrative. The one exception, perhaps, is Charles II’s years of exile, where the author supplies more of a story. At times, one almost feels that a larger book was intended, maybe a life of Charles I or perhaps more probably a life of Charles II. Certainly I wished that either biography had been written, and the wish grows stronger as one reads The Image of the King. Nevertheless the book at hand is a remarkable one and immensely readable.

Richard Ollard has devoted a great deal of his career to the seventeenth century, and Charles II appears in all of his four books. What he has written is therefore the result of the research of half a lifetime’s study and contemplation. It does not at all detract from Antonia Fraser’s biography to say that had Richard Ollard’s book appeared first she would have gained by reading it. Certainly it should not be missed by anyone interested in the Stuarts or in the personalities of Charles I and Charles II: indeed any reader will be greatly stimulated by reading it.

Ollard writes compassionately but from strong moral convictions and principles: to some extent from religious principles (although I would hasten to add not denominational in any way). Certainly he is concerned with the morality of actions and of personal relationships. Hence although he realizes and sympathizes with Charles I’s principles—his strict sexual morality, his dedication to Anglican beliefs, and his almost religious sense of the duties as well as the authority of kingship—he condemns his actions, not only his betrayal of his loyal follower Strafford, when he signed the bill of attainder leading to his death, but also his deceit, his chicanery, his devious plotting, the elasticity of his conscience (about which he prated so frequently) when he thought that the means of deceit might serve the re-establishment of his authority.

Ollard is fascinated by the image which Charles I projected of himself—through his court masques, through the Van Dyke portraits, through the Eikon Basilike, his purported spiritual auto-biography, and the final theater of death and martyrdom. And it is Ollard’s intention to show how that image has survived down the centuries as well as assessing how far it corresponds to the reality. And in this analysis are some of the wisest things that have been said about Charles I—for example, Ollard shows how indecisive, how easily dominated first by the Duke of Buckingham and then by his wife Henrietta Maria, was this man of principle.

The only fault that I have to find with this remarkable portrait is that Ollard might have put more stress on the effect of Charles I’s physical inadequacies—his stutter and his diminutive height—both in strengthening his beliefs and also in driving him into the private world of aestheticism where principles abounded in pretty verse and harsh realities were excluded. And maybe, too, he keeps Charles I’s aesthetic interests too sharply separate from his religion. Charles loved the beauty of holiness, decorum, and the ritual of the Laudian Church: he found there a religious masque for himself if not for his nonconforming subjects.

Kingship like a greenhouse forces whatever is locked within. Both Charles I and Charles II would probably have made only modest achievements as subjects. Charles I might have become a Laudian bishop with an excellent style in sermons (he wrote good prose) and Charles II would have made a good sailor—indeed, he did more for the Navy than any other monarch. He did precious little else except keep his country from crumbling again into civil war—not a minor feat but, as Ollard shows, due more to luck than to judgment.

Ollard is harsh but just about Charles II. He shows that he could be vindictive, that he could be extremely callous as well as casual in his treatment of old, tried servants of the Court, such as the Earl of Clarendon or the great Irishman, Ormonde. The shallowness of Charles II’s character Ollard stresses and demonstrates time and time again. Ollard implies that his survival—even his Restoration—had little to do with either his actions or his temperament. At times Ollard, like Clarendon, borders on the censorious. After all no part is more difficult to play than that of an exiled monarch, particularly for one so young as Charles II: he was on the run from the age of fifteen. Nor is the part of restored monarch much easier. And in spite of all, to be as affable as Charles was, as tolerant of face to face criticism, to have been only somewhat callous and somewhat vindictive—all this was in remarkable contrast to other monarchs of Charles II’s time and testifies to the basic generosity and tolerance of his temperament.

Advertisement

Perhaps it is not surprising that Ollard should say very little about Charles’s relationship with women except to bring out the horror of Castlemaine’s character—one of the most detestable women ever to ensnare a monarch. On this subject, I think, Ollard could have read Antonia Fraser with advantage and learned that there was a dimension of Charles II’s character that has evaded him. At the core of Charles II’s temperament there was a sad and sardonic sensualist who threw a shadow over other facets of his character. Charles II lived with a kind of despair, an accepting fatalism which may be why he was so half-hearted about his religion and his politics.

Both kings, as Ollard points out in his two last fascinating chapters, projected strong images of themselves for posterity which, owing to the nature of English political development, remained powerful and emotive even to the twentieth century. Both images—that of king and martyr for Charles I and that of Good King Charles of the Golden Days for his son—have done much to obscure the true nature of their personalities. These images Ollard whittles away to discover the dross beneath the gold. What emerges is a just yet compassionate study of two complex, muddled, fissured human beings caught in the most difficult of crafts—kingship—a craft at which they both were poor performers: plots and rebellions against them were their lot and they both diminished the institution which they should have adorned. It needed a Dutchman, William III, and some cousins, the Hanoverians, to rescue the British monarchy from the effects of their rule.

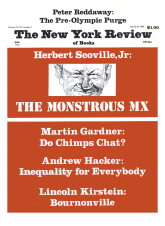

This Issue

March 20, 1980