In response to:

Must We Copy Japan? from the February 21, 1980 issue

To the Editors:

I was disappointed to read Tetsuo Najita’s review of my book, Japan as Number One: Lessons for America [NYR, February 21]. I was disappointed not because The New York Review chose as reviewer an American nisei specialist on Tokugawa history who has apparently not kept up with recent developments in Japan. (He repeats many arguments of Japanese intellectuals popular in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but he is apparently unaware, for example, that the effects of economic growth are so great that by now Japanese welfare benefits even from government sources have surpassed those of England, which is not bad for a country where thirty years ago people were dying from side-effects of malnutrition. In these days of energy shortage, does Najita really believe Japan should build more roads rather than railroads?)

Nor was I disappointed because he misinterprets my argument. (I made clear in my preface that I was concerned with lessons for America, and housing is obviously not a place where we can learn from Japan. I never said we should “imitate” Japan but should learn from Japan’s successes in ways that fit our tradition.) Nor was I disappointed because he accused me of neglecting problems which I discussed. (I ask the reader to look at Chapter One and the conclusion and judge for himself whether I am “blinded” to the problems raised by Najita.) Nor was I discouraged by his statement that many Japanese will not find my comments helpful. (Over 440,000 copies of my book in hardback are already in circulation in Japanese translation, and my Japanese publisher tells me that in a month or two my book will become the all-time nonfiction best-seller written by a foreign academic. I wish I could fulfill the requests to speak and write in Japan.) Nor was I disappointed because he misunderstands America. (To say that the effect of special interests in America is to offset each other is at best to underestimate the extent to which special interests are bleeding our country. Many of America’s largest corporations, aware of Japanese successes, are profitably studying Japanese examples, and to describe this as a farce is to show little awareness of the process or results.)

I am disappointed because it reinforces American provincialism, self-satisfaction, and European-centrism at a time when America is rapidly going the way of England as a declining power, and when East Asia is already the world’s most dynamic center. It may be comforting for many European-centric financially well-endowed people in America as in England to retreat to their pleasures and ignore what is happening to the country. I am discouraged because it does not bode well for our future that Americans will be able to find an intellectual rationale for unjustified provincialism which even Najita decries. Even European countries are ahead of the United States in developing industrial policies, and continued complacence is not in our national interest. Recent statistics show that Japanese industrial production is already three-fourths that of America’s or one and a half times America’s per capita production. If current trends continue it will easily surpass the US in absolute terms as an industrial power in the mid-1980s with consequences for American unemployment, decreasing tax base, and protectionism. I can only hope that the provincial self-satisfied Americans who find it unpleasant to acknowledge the scope of Japanese successes will allow some of us concerned about America’s declining economy, rising crime rates, low educational standards, and centrifugal forces to broaden the discussion of how we might deal with the issues confronting our country.

Ezra F. Vogel

Chairman, Council on East Asian Studies

Harvard University

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Tetsuo Najita replies:

Mr. Vogel’s opening remarks in his response to my review contains a racial reference which may, be virtue of its grammatical inconsequentiality, have escaped your notice.

He refers to me as an “American Nisei.” Nisei, of course, indicates second generation Japanese Americans whose fate during the Second World War is by now a familiar subject, but in this context deserves mention. It remains unclear to me why ethnicity should be used to qualify scholarly criticism. Indeed, if such were the case, Mr. Vogel would be hard-pressed to defend his explication of Japanese culture.

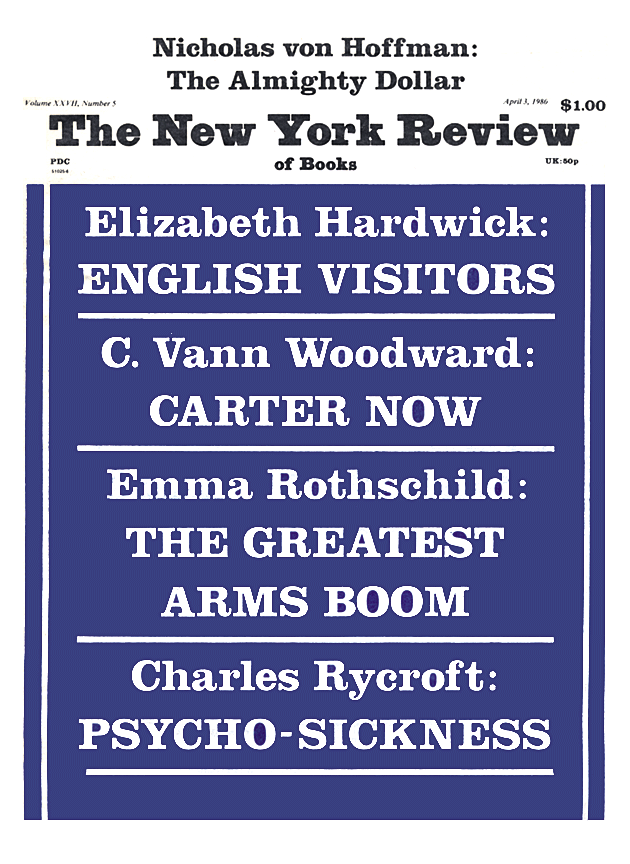

This Issue

April 3, 1980