It has been common in surveys of the arts to treat the twelve years of Hitler’s Thousand-Year Reich as an insignificant break in the story of the modern movement—something too contemptible for serious consideration. Historians, critics, and exhibition organizers, on coming to the 1930s, have concentrated on those parts of the globe (like England and the United States) where the innovations of the 1920s were still being fruitfully absorbed; elsewhere they have either cut the story short, as in the big Paris-Berlin and Paris-Moscow exhibitions at the Centre Beaubourg, or simply skipped its more embarrassing aspects. Thus “following the enforced suppression of artistic creation during the period 1933-1945,” says the otherwise very useful Ullstein Kunst Lexikon of 1967, “German art sought to renew its connections with modern artistic tendencies through W. Baumeister, E.W. Nay, G. Meistermann and others.” That is all. Today, however, especially in Germany itself, and especially now that the very idea of modernism has come to seem a bit old-fashioned, it has become natural to wonder just what did happen in those blank years. Surely “artistic creation” did not simply come to a stop. Was there perhaps (to use a fashionable term) some kind of alternative culture?

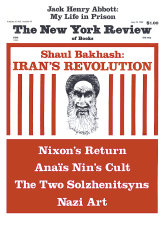

There was, with a vengeance, and nobody who experienced it will ever forget it. Following a short period of uncertainty as the Führer’s ideas percolated downward, by 1937 the new National Socialist art and architecture were all too solidly there for the world to observe. That year three great exhibitions were mounted in Munich, the cradle of the Nazi party: first, in July, the inaugural “Great German Art Exhibition” in the House of German Art designed by Hitler’s favorite architect Paul Ludwig Troost and opened by the Führer himself; then a day later the “Degenerate Art Exhibition” organized by his pet painter Adolf Ziegler; finally in November, to lend good taste to the whole operation, the all-out anti-Semitic show in the Deutsches Museum “Der ewige Jude,” “The eternal Jew.”

Angered by the award of the Nobel Peace Prize the previous year to the antimilitarist Carl Ossietzky, then a concentration camp inmate, Hitler banned all Germans from the Nobel awards and instead founded his own German National Prizes for art and science (naturally omitting peace). The “Great German Art Exhibitions” were to become the only representative exhibitions each year, thereby not only making Munich “the capital of the Movement” but Germany’s artistic capital too. Meanwhile in Paris a world fair was being held at which Albert Speer’s lofty pseudo-classical, heavily be-eagled German pavilion exactly represented the new style and spirit of the reborn arts. With a certain cynical aptness the French organizers located a site for it facing the almost equally large and pretentious pavilion of Stalin’s USSR.

Like the ceremonial book-burnings of May 1933, the Munich Degenerate Art Exhibition has become a familiar item of Nazi history (there was also a rather less well known Degenerate Music Exhibition at Düsseldorf in the following year). These great philistine gestures showed the almost visceral detestation of the Nazi leaders for the internationally alert, socially rooted culture of the Weimar Republic and the formal innovations that were its hallmark—particularly those which involved distortion of the human face and figure. With them went a number of deliberate steps to stamp out modern art. Artists were sacked from their teaching jobs and forbidden to exhibit or even, in some cases, to paint; the Bauhaus was shut for good; museums were purged of “degenerate” works which were sold abroad, or pillaged by prominent Nazis like Goering, or eventually burned by the Berlin Fire Service.

The pernicious concept of “degeneracy,” first popularized by the Zionist doctor Max Nordau at the turn of the century, now formed part of the Nazi doctrine of race: “Entartung,” the German term for degeneracy, meant deviation from the “Art,” the species, something that was by no means a species in any objective scientific sense but stood in right-thinking minds for the racially pure Nordic, Aryan stock from which the Third Reich was to be brewed. By these standards, if by no other, the Jews could logically be identified with the modern culture which the leaders so hated; the same terminology, the same gut reaction, and in due course the same policy of total eradication were applied to both.

But what about the “positive” side? What was the alternative National Socialist culture actually like? The answer was clearly to be seen in the House of German Art and the pages of the magazine Die Kunst im Dritten Reich founded the same year. The architecture was massive, marmoreal, with rows of columns like well-drilled soldiers, based on the modified classicism of Karl Friedrich Schinkel, greatest of Prussian architects and a model for many moderns including Mies van der Rohe. Outwardly “representative” and fit for ceremonial parades, such buildings had interiors like immense luxury hotels or showy trans-Atlantic liners (Troost had actually graduated from designing these) with long perspectives, simple but expensive detailing, and monster chandeliers.

Advertisement

In such a setting the sparsely hung, heavily framed works of selected German “artists”—about six or seven hundred of them each year—seemed all of a piece with the regime and its ideals. This was not because the painters were conducting deliberate propaganda for the regime, aside from the more or less ghastly portraits of the leaders (which scarcely count, since portraits of leaders are likely to be mediocre under any regime) and the brutal-mouthed storm troopers by Elk Eber, former war artist and holder of party card number 1307 since 1923, the year of the Beer-Cellar Putsch. No: it was the actual artistic qualities of these pictures and sculptures that inspired the viewer to the same sense of nauseated rejection as he felt on seeing a parade of dumb but disciplined SA men or hearing a Hitler speech.

It is easy to laugh now at the awfulness of many of these works: at Wolf Willrich’s insipid nude, for instance, with a swastika symbol at her feet and the title Noble Blood (Edles Blut), or the same artist’s extremely pregnant strong-chinned blond lady tastefully dressed in a loose robe, a vestige of a halo, and a wedding ring, and called The Guardian of the Species (Die Hüterin der Art). Willrich, whose book The Cleansing of the Art Temple (Säuberung des Kunst-tempels) was an important part of the anti-modern campaign.

At the time, however, it was by no means so certain that the Nazis’ ideas and imagery were not going to dominate the world, with the result that there was a threatening edge of horror to even the tamest and most conventional of the approved works. Actually, programmatic party pieces were in a minority there, far outnumbered by such seemingly unpolitical exhibits as naturalistic peasant groups, traditional German landscapes and paintings of cattle, portraits of society ladies dressed in the height of Berlin 1930s fashion, Düreresque graphics and nude classical bronzes of an athletic or arcadian kind. They might be by artists of some merit, like the sculptor Georg Kolbe, whose figures were not all that far from those of Maillol and Lehmbruck. In the context of Nazi ideology, however, they were even more alarming, for they showed how certain already prevalent German traditions and characteristics could be harnessed to the Nazi cause. What is more, they recalled corresponding features in the art of other countries—the kind of tame classicism, flashy Italianate portraiture, sub-Barbizon rusticity, and lumpy earthiness that could be found also in London, Rome, Paris, and New York. And this suggested to some contemporary observers that the democracies too might be not quite so immune to the Nazi ethos as they would like to think.

It was a nasty time and a nasty art. Now of course we know more about it: about the four years preceding the 1937 exhibition, for instance, when enough still survived of Expressionism in art and literature, and of the international style in architecture, for some of their more racially and politically acceptable practitioners to think they might be able to go on working under the new apparatus of control.

So Barbara Miller Lane (in her excellent Architecture and Politics in Germany 1918-1945) was able to show Mies van der Rohe and Peter Behrens joining Goebbels’s monolithic Chamber of Culture, while Gropius in May 1934 was still trying to persuade its officials that the moderns were Schinkel’s true heirs. Dix and Schwitters were at that time also members of the Chamber; Nolde was counting on his long-standing membership in the party to tell in his favor; the novelist Gottfried Benn was still enthusiastic for its idea of racial perfection. For a short while the issue was uncertain enough for the Marxist critic Georg Lukács in Moscow to make his now notorious attacks on Expressionism as a contributory factor in the rise of the Nazi ideology (a view which he could never have sustained if he had not been deaf to the musical evidence and blind to that of art). But right from the outset Hitler himself had laid down the lines for what was to come, and any differences between his more (Rosenberg) and less (Goebbels) lunatic disciples were in the long run unimportant.

“Art,” the leader told the Nuremberg party rally in his first year of office,

is a noble mission and one which calls for fanaticism…. The National-Socialist movement and its leadership cannot allow such incompetents and charlatans suddenly to change allegiance and to move into the new state as if nothing had happened, with a view to dominating its artistic and cultural policies as before. Whatever happens we are not going to have these elements distorting the cultural expression of our Reich; for this is our state, not theirs.

Ever since the First World War (so he said later) Hitler had dreamed of giving Munich “a new great exhibition palace for German Art.” The old Glaspalast which had housed the annual summer exhibitions there in the city’s heyday as an art center was destroyed by fire in 1931, and although there had been plans for a modern building to replace it in the last years of the Weimar Republic they had not been carried out. Accordingly Hitler in 1933 treated this as “the first great task” of the Third Reich, and commissioned Troost—who had already designed the party’s Brown House—to build what he termed a temple “not for so-called modern art but for a true eternal German Art, or better still a house for the art of the German People, and not for some kind of international art of the year 1937, 40, 50 or 60.” From the first, according to his speech at the opening, he had determined to take such decisions without discussing them with anybody else.

Advertisement

Hitler, then, saw himself as the progenitor of a new, strong, timeless German art. What he did however was to promote the more conservative Munich artists to be in effect the visual spokesmen of his ideas. Even under the Republic Munich had hardly been an avant-garde center: the Blaue Reiter artists had long since dispersed, the Magic Realists of the mid-Twenties were influenced by Fascist Italy rather than the Neue Sachlichkeit of Dresden and Karlsruhe and the ex-Dadaists. Only a handful of painters like Max Unold and Adolf Erbslöh stood out against the old local tradition of naturalistic genre and peasant painting in the style of Grützner and Defregger. Mixed together with similar conservatives from north Germany (including Mackensen and Modersohn of the Worpswede school) and a new sprinkling of pure Nazis such as Eber and Willrich and the muscle-bound sculpture specialist Josef Thorak, these previously obscure people aligned themselves effortlessly, and even perhaps unconsciously, with the mental and spiritual world of the Reich. That is to say, with Blood and Soil for the men, Kinder, Kirche und Küche for the girls, heroism and comradeship for the army, organized sadism for the Kämpfer, and the ennoblement of work for all the rest.

A largely pre-existing body of art was brought to the surface and given a central place. Then less than ten years later virtually the whole thing vanished underground once more. The building itself still stood, and stands in Munich today as the House of Art, but the works which it contained are no longer hanging in any German collection. Some, dealing specifically with war themes, were taken home by the US occupation forces to form a special collection for the Defense Department; others were brought to a central collecting point and are now in a Munich depot managed by the Federal Ministry of Finance; those left over from the last of the Great German Art Exhibitions are in the reserves of the Bavarian state collections. Works with specifically Nazi allusions were weeded out and have seemingly disappeared. It was only in 1974 that a first public showing of pictures from these previously invisible sources was organized in Frankfurt-am-Main and then toured to Berlin and to other West German cities.

The first German books to deal with this difficult subject concentrated likewise on the Nazi campaign against “degenerate art.” In 1949 Paul Ortwin Rave published his short, sober, and informative Kunstdiktatur im Dritten Reich, which remains an invaluable sources in 1962 appeared Franz Roh’s Entartete Kunst with a reproduction of the catalogue of the 1937 show and a gallery-by-gallery examination of the fate of the confiscated works. Right up to the Frankfurt exhibition the only study of the “positive” aspects of Nazi art policy was American: Helmut Lehmann-Haupt’s Art under a Dictatorship (Oxford University Press, 1954); and this book seemed to set the tone for the “establishment” view among Western art historians and critics.

Lehmann-Haupt’s concern was not so much to relate the art of men like Thorak and Arno Breker, Eber and Adolf Wissel to aspects of German tradition or specifically Nazi ideology as to link its backward-looking rhetoric and sentimentality with dictatorship as such. Formal similarities between Nazi art and architecture and those of Stalinist Russia were used as evidence that all dictatorship meant the enslavement of the artist—and also as an incidental stick with which to beat William Morris and other advocates of a popular, socially engaged art. That this argument overlooked the very different artistic development of Mussolini’s Italy was not discussed.

Berthold Hinz’s equally important but much more fully illustrated book appeared first in German at the time of the 1974 Frankfurt exhibition, and part of its aim was to combat Lehmann-Haupt’s view. Its present title Art in the Third Reich is in fact borrowed from the paperback version of that exhibition’s catalogue (published by a direct-mail Frankfurt firm called 2001) to which its author contributed two essays. Originally the book was called Die Malerei im deutschen Faschismus and bore the subtitle “Art and Counter-revolution.” Those titles were perhaps more indicative of Hinz’s thesis, which is that the issue that matters—in art as in all other aspects of life—is not that of dictatorship or democracy but the choice between fascism and socialist revolution. Nonetheless fascist Italy is once again left out of the reckoning, though illuminating comparisons and contrasts could have been made with regard to coexistence under Mussolini of a placid pseudo-classicism on the one hand and an innovatory futurism on the other—not to mention the exemplary and largely isolated figure of Giorgio Morandi, an artist whom no other dictatorship could match.

This time any formal kinship with Soviet Socialist Realism of the 1930s and 1940s is dismissed by the author as irrelevant, on the ground that

Not only are the dominant modes of art in these two political systems different in origin, a key factor in distinguishing between them is their divergent attitudes toward reality. Two major themes of Soviet art, the truck driver and the female tractor driver, do not occur at all in the art of the Third Reich….

So Hinz writes in the new foreword written for the American edition, which has not merely been competently translated but has been happily revised throughout in such a way as to get rid of much of the clotted sociologese of the original German. But the book’s angle of attack still remains almost entirely social and political, so that it is always the tangible (or “concrete”) subject of the work of art that is discussed rather than its intangible spirit and style.

Hinz seems to approach the National Socialists as if they were rational beings, concerned above all with the message and political commitment of a picture or statue, and setting out to manipulate the arts primarily in order to gain practical control of the media. The origins of the Nazi ideology are “quite unimportant”; the campaign against Expressionism is ascribed not to Hitler’s clouded imagination but to “political strategy.” Percentages of works devoted to different themes are measured in order to establish “the structure of painting under German Fascism” or “a phenomenology of aesthetic expansion in National Socialism.” But even if you cut out the jargon—and there is still quite a bit left, as these phrases show—this mechanistic approach conveys far less than a few direct quotations from the Nazi leaders and their aides: the kind of documentation that Joseph Wulf provided in his Die Bildenden Künste im Dritten Reich (1963) or Hinz himself in the five speeches by Hitler reprinted in the German edition of his book. Even in the new version it is a section of an official wartime brochure on “The New German Painting” whose language and attitude do more than anything else to bring the art of the time nauseatingly back to life.

If Hinz finds it difficult to do this by his own writing (useful as it is in its analysis of art’s themes, functions, and titles) it is largely because he is handling concepts rather than judging by his eyes. Some of these concepts moreover seem idiosyncratic, to say the least, from an art historical point of view. Thus “genre” painting, to which he rightly gives a central place in Third Reich art, is extended to embrace landscapes, animal pictures, seascapes, and even war paintings, while ruling out “the work and organization of society” (what about Millet then, or for that matter Hogarth?) and any element of involvement or tension.

If this gentle treatment of familiar themes was really what the Nazis most wanted, why did they not, like the typical bourgeois the author takes them for, admire the placid, contemplative, essentially middle-class art of Renoir, Degas, Mary Cassatt, and the later Vuillard? Again, was “genre” simply a debased realism, based not on the new Realism of mid-nineteenth century France (with it roots in the Le Nains and the seventeenth-century Spaniards) but on what Hinz calls “the reception, across the span of more than two hundred years, of the high point of Dutch and Flemish painting”? Of course Dutch painting was an element in the mixture of styles that was approved of by the Nazis. But Hinz seems to me utterly wrong in excluding the powerful influence of the established Realism of the 1860s, when the French Second Empire had at last come to terms with it and a number of German artists—Leibl, Scholderer, Louis Eysen, more briefly Hans Thoma and Victor Müller—came to Paris to be lastingly impressed, in particular by Courbet’s work.

Politically conscious writers on art tend to regard Courbet as sacrosanct because of his professions of socialism and the inexcusable reprisals which he suffered after the suppression of the Paris Commune in 1871. But the pictures that he was painting in the later 1860s—large stag pieces and the odd stimulant for a tired Turkish ambassador; in Munich he was even invited to paint scenes from Lohengrin on Ludwig II’s bedroom walls—were not only pleasing to Napoleon III’s art administration but would have fitted only too well in the House of German Art or the 1937 Berlin exhibition of Hunting Art. Not that this was what Leibl and others were seeking from Courbet. Their concern was rather with his genuinely and subversively realist pictures such as The Stone-Breakers, which was shown in Munich in 1868. The influence of his style and technique however is plain to see, first in Thoma’s landscapes and Leibl’s Bavarian peasant pictures (like The Women of Dachau, a title with awkward overtones today), then through them in such works as the very competent peasant portraits by Constantin Gerhardinger, technically the most gifted of Hitler’s artists. Indeed a substantial proportion of the Third Reich’s group scenes or portraits—whether of peasants, workers, or uniformed Nazis—reflect this type of latter-day realism, inherited sometimes from Courbet’s disciples, sometimes more remotely through the socially conscious Düsseldorf painters who also had contacts with Paris at that time.

The analogy is not so much with the first-generation Realists as with those secondary artists who were echoing them around the turn of the century: Léon Lhermitte for instance, Mihály Munkácsy or Emile Claus. Hodler too is a perceptible influence, though he developed realism in his own way to make something at once more symbolic and hierarchical and more formally organized; his example may have come partly through the Austrian peasant painter Albin Egger-Lienz. A watered-down version of Barbizon painting is often visible too.

But are these origins in fact so very different from those of certain socialist realists? The dominant Russian school of the 1930s and 1940s, while beginning earlier and ending much less abruptly than its German counterpart, likewise traced its heritage to a group of artists who came to maturity in the 1860s, the Peredvizhniki or society of traveling painters led by Kramskoy and Perov, specialists too in social themes and scenes of village life akin to those of the Belgian Realist Charles de Groux and the immensely successful Rhinelander Ludwig Knaus. Hinz thus seems to me quite wrong in attributing different origins to the two schools. And whereas there were others who shared the same iconographic heritage but made something very different of it (as did Van Gogh), with both these schools the style and vision, and even at times the composition, still bore a pre-impressionist stamp. True, the one group might paint mechanized peasants and the other a more sedentary or horse-drawn brand, but in style and vision they resembled each other because they both stopped the clock before 1874.

Certainly we owe Professor Hinz much for dragging out Nazi art from under the mat, and his 160-odd illustrations (which are a lot better reproduced than in the original edition) will for many people and institutions be worth the price of the book. He has not made the common mistake of thinking that the sight of these things will be too corrupting for the present-day reader or, alternatively, that they are too aesthetically insignificant to discuss. But the fact remains that he himself was not yet born at the time of the great 1937 exhibitions, and to think himself back imaginatively into the mentality of the Thousand-Year Reich is more than he can manage. The same failing seems to have underlain the catalogue of the 1974 Frankfurt exhibition, to judge from the reprint, which sadly repeats the errors of the German Communist Party at the time. That is to say, evidence is adduced on the one hand to show that the enforced change of artistic outlook and expression (which of course ran through all the arts) was only a cloak for measures to control political opinion, and on the other to reveal that the regime was continually depressing wage levels and working-class living standards for the benefit of large-scale capitalism. Right; but why then did the victims not object? On the contrary it was generally agreed during the Second World War that the Germans, workers and all, were solidly behind their leader at least until Stalingrad was lost. And if this went against their material interests it must have been because of some more powerful, if less “concrete” motive.

The truth is that Hitler’s racial and ideological program, however crazy it may seem today, had an immense appeal to Germans of all classes, particularly in the Rhineland and the South. The people liked being a Volk, and were accordingly willing not only to vote and shout and parade for Aryanization, Blood and Soil, the Nordic Race, and the rest of the murderous rubbish, but also to accept shortages and deprivations, and to fight and die in the hope of imposing such ideals on the rest of the world. Ideas, ecstasies, spiritual states, however confused, can, in short, count for much more than any sober material considerations; they may have been promoted in the first place by specific material interests (just as Hitler himself was promoted by German industry) but they soon take on a life of their own where they become stronger than their backers. Seen thus, the importance of Nazi art and architecture is that they remain an outward and visible sign of these immense intangibles, and their real evidence lies not in any ostensible subjects but in the way these are handled. Style is crucial, just as language is crucial; the Nazis so put their mark on them both that a few words in a speech or article, a quick look at a building, statue or picture, could imply all the rest of the ideological package, and with it the measures to which that package led.

It is still a relevant issue, because once again there is a reaction against the modern movement, if for rather different reasons than in the case of the Nazis. As Hinz points out, West Germany’s rehabilitation and reassimilation of the moderns after the war was complete by about 1955, and since then the old concept of artistic “progress” by means of successive formal innovations operating through a self-renewing avant-garde has no longer seemed to apply. Much is nowadays being questioned that once seemed self-evident to right-thinking cultural progressives: the profundity of nonobjective art, the audibility of musical serialism and the actual functioning of functional architecture. One way and another modernity is no longer an article of faith. That being so, there is every reason to examine the effects of the last great reaction of the same kind, particularly since it was not in the first place merely imposed by the politicians but had its roots in the public’s resentment and the movement’s own loss of impetus and assurance toward the end of the Weimar period.

Take architecture, for instance, where the reaction at present seems to be most vocal: has the current vogue for the highly imaginative buildings of Rudolf Steiner nothing to do with his equally imaginative doctrine of anthroposophy and the wishy-washy art to which this led? How about the comfortable neo-traditionalist domestic architecture of Paul Schultze-Naumburg’s middle years: can its now fashionable type of conservatism be wholly divorced from this architect’s ideas about racial art and his vandalizing of the former Weimar Bauhaus? Some at least of the values which the culture of the Third Reich set out to proclaim—optimism, Bejahung or the spirit of enthusiastic assent, racial perfection, masculine comradeship and struggle, feminine submissiveness—are still being visibly asserted elsewhere today, even if only on magazine covers, cinema posters, and cornflake packages. In the materialistic societies of the late twentieth century, ideology perhaps counts for very little. But we should not forget that there are times and places where it can move mountains—for better or for worse.

This Issue

June 26, 1980