#####1

It is good for strangers

of few nights to love each other

(as she and I did, eighteen years ago,

strangers of a single night)

and merge in natural rapture—

though it isn’t exactly each other

but through each other some

force in existence they don’t acknowledge

yet propitiate, no matter where,

in the least faithful of beds,

and by the quick dopplering of horns

of trucks plunging down Delancey,

and next to the iron rumblings

of outlived technology, subways up for air,

which blunder past every ten minutes

and botch the TV screen in the next apartment,

where the man in his beer

has to get up from his chair over and over

to soothe the bewildered jerking

things dance with internally,

and under the dead-light of neon,

and among the mating of cockroaches,

and like the mating of cockroaches,

who were etched before the daybreak

of the gods with compulsions to repeat

that drive them, too, to union

by starlight, without will or choice.

It is also good—and harder—

for lovers who live many years together

to feel their way toward

the one they know completely

and don’t ever quite know,

and to be with each other

and to increase what light may shine

in their ashes and let it go out

toward the other, and to need

the whole presence of the other

so badly that the two together

wrench their souls from the future

in which each mostly wanders alone

and in this familiar strange room,

for this night which lives

amid daily life past and to come

and lights it, find they hold,

perhaps shimmering a little,

or perhaps almost spectral, only the loved

other in their arms.

2

Flying home, looking about

in this swollen airplane, every seat

of it squashed full with one of us,

it occurs to me I might be the luckiest

in this planeload of the species;

for earlier,

in the airport men’s room, seeing

the middle-aged men my age,

as they washed their hands after touching

their penises—when it might have been more in accord

with the lost order to wash first, then touch—

peer into the mirror

and then stand back, as if asking, who is this?

I could only think

that one looks relieved to be getting away,

that one dreads going where he goes;

while as for me, at the very same moment

I feel regret at leaving

and happiness to be flying home.

3

As this plane dragging

its track of used ozone half the world long

thrusts some four hundred of us

toward places where actual known people

live and may wait,

we diminish down into our seats,

disappeared into novels of lives clearer than ours,

and yet we do not forget for a moment

the life down there, the doorway each will soon enter:

where I will meet her again

and know her again,

dark radiance with, and then mostly without, the stars.

Very likely she has always understood

what I have slowly learned

and which only now, after being away, almost as far away

as one can get on this globe, almost

as far as thoughts can carry—yet still in her presence,

still surrounded not so much by reminders of her

as by things she had already reminded me of,

shadows of her

cast forward and waiting—can I try to express:

that love is hard,

that while many good things are easy, true love is not,

because love is first of all a power,

its own power,

which continually must make its way forward, from night

into day, from transcending union always forward into difficult

day.

And as the plane descends, it comes to me,

in the space

where tears stream down across the stars,

tears fallen on the actual earth

where their shining is what we call spirit,

that once the lover

recognizes the other, knows for the first time

what is most to be valued in another,

from then on, love is very much like courage,

perhaps it is courage, and even

perhaps

only courage. Squashed

out of old selves, smearing the darkness

of expectation across experience, all of us little

thinkers it brings home having similar thoughts

of landing to the imponderable world,

the transcontinental airliner,

resisting its huge weight down, comes in almost lightly,

to where

with sudden, tiny, white puffs and long, black, rubberish smears

all its tires know the home ground.

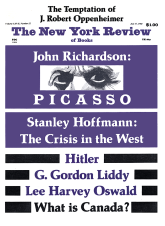

This Issue

July 17, 1980