Mordecai Richler’s characters could never be convicted of loitering. After scuffling away their boyhoods on Montreal’s St. Urbain Street—scratching obscenities into the walls of drugstore phone booths, lusting after girls who shoot by, cradling schoolbooks against their pert breasts—Richler’s working-class Jews are catapulted into a sea of hostile goys, who dip and dart like sharks. “Our world was rigidly circumscribed,” writes Richler in his collection of reminiscences, The Street. “Outside, where they ate wormy pork, beat the wives for openers, didn’t care a little finger if the children grew up to be doctors, we seldom ventured, and then only fearfully.” Fear turns to envy and resentment once the St. Urbain irregulars compete in college and conference rooms with these cool, lean, crisply dressed Gentiles. “A plague on all the goyim, that’s my motto,” a scrap-yard owner tells Duddy Kravitz in The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, drawing a finger across his throat to indicate his attitude toward even his best customer. So after Duddy screws everyone in his path to hit it rich, he still isn’t able to relax; he gloats, schemes, always suspects the worst. He’s even unfaithful to his adoring wife, explaining that she’s bound to be unfaithful to him eventually—“This way I get my licks in first.” It’s this air of hustle and betrayal that gives Richler’s fiction its nervous, horny hum.

Like Richler’s previous novel, St. Urbain’s Horseman, Joshua Then and Now is about a minor-league Jewish celebrity whose life ignominiously caves in. In St, Urbain’s Horseman, a movie-TV director named Jake Hersh finds himself in the docket for aiding and abetting the sodomy-rape of a German au pair girl; he has waking nightmares in which “big goysy queens” goose him on the way to dinner. Joshua Shapiro, journalist and Canadian Broadcasting talking-head, is married to a sexy, bronze-limbed shiksa named Pauline, who arouses his libido whenever she scampers down to the tennis court in her smart white outfits. Even with three kids and a successful career, Joshua finds himself at the age of forty-seven glumly sliding into a middle-age slump. Joshua notes regretfully that his drooping stomach now blocks his view of his penis. He resolves to flatten his stomach by his forty-eighth birthday so he can greet it with a jaunty hello. “Good morning, big boy.”

Sagging flesh is the least of Joshua’s woes, however. As the novel opens, Joshua, recuperating from cracked ribs and multiple fractures, discovers that he has become a martyr-hero to homosexuals up and down North America because of an alleged affair with the novelist Sidney Murdoch. A photograph showing the two of them kissing appears in Christopher Street, followed by pages of excerpts from an erotic correspondence the two of them concocted as a larky scam two decades earlier in London. (Splashed around the excerpts are advertisements for macho gay gear: “The Jac-Pack is a hot hole you can really get into! Like natural flesh, it surrounds your every nerve ending with erotic sensations.”) Also in the mail is a letter from the David and Jonathan Society—“a newly formed group of young, caring Jewish faggots”—inviting him to be guest of honor at their Purim ball. Funny? Perhaps; but every time Joshua laughs, his ribs ache.

A slapstick farce, Joshua Then and Now shuttles back and forth in time, tracing Joshua’s bunged-up life from his boyhood in a St. Urbain cold-water flat to his misadventures in London bed-sitting rooms and Hollywood bungalows. It’s a book full of pranks, excursions, roguish couplings, and smutty wisecracks, but the look!-we’ve-come-through exuberance of Richler’s earlier work is sadly missing. As Joshua rattles from decade to decade the novel turns into a male-menopausal moan, a lament for lost energy and idealism in a tone of intellectual condescension and racist rancor. Richler scores easily (too easily) off New Statesman radicals and Hollywood liberals, scattering these pseuds like pins into the gutter. Swept into the gutter with them are the objects of radical-chic agitation: Third World blacks. Joshua first catches the beautiful shiksa Pauline at a London party in the clinch with a West Indian writer. He quickly works himself up into a hateful froth. “And what if he found her necking with some pink-tongued, big black ape? Murder, that’s what.” Later, Joshua refers to Pauline as “a nigger-loving whore,” and later still he stalks her at a Hampstead fund-raiser—“She had to be there with the other nigger-lovers.”

Of course, Joshua’s outbursts can be explained away as the spasms of a mind twisted with jealous rage, but they’re still coarse, particularly in a novel which prides itself on its heart-bruised Jewish sensitivity. Besides: even in calmer moments, Joshua acts as if all blacks make their homes in the trees.

Advertisement

Jews, Jews, Joshua thought, everywhere I go are other Jews to advise me. Clutching. Claiming. I probably wouldn’t even be safe in Senegal. Some big buck, his face reamed with tribal scars, his voice whiny, would drop out of his banana tree to grab my hand and say “Shalom Aleichem.”

If Jews are everywhere, so are their enemies. In St. Urbain’s Horseman, Jake Hersh is obsessed with the infamous Nazi sadist, Dr. Mengele; in his dreams he nails Mengele in Paraguay, using pliers to pull the gold fillings from his upper front teeth. Joshua, who writes a book on the Spanish Civil War, is obsessed with an enigmatic German with nicotine-colored hair and two doctorates whom he met in Ibiza in 1952, Dr. Dr. Mueller. Convinced that Mueller is a piece of Nazi scum, Joshua humiliates him in front of a group of Spanish officers; in retaliation, Mueller has Joshua driven from the country on a trumped-up charge. A sensible person would chalk it all up to experience, but Joshua can’t get the foul Mueller out of his mind—he longs for a triumphant shame-clearing reckoning. “Ibiza, Ibiza,” is the novel’s nostalgic sigh. “Ibiza, Ibiza.” After twenty-five years of sulking Joshua finally returns to Spain, and his long-awaited rematch with Mueller turns out to be an anticlimactic fizzle. Mueller has been dead for years (cancer), his villa leveled to make way for a condo called—crashing irony—The Don Quixote Estate. What Richler seems to be saying is that the great stirring causes are all past, leaving misfits like Joshua to gnaw on petty grievances, tilt at puny windmills.

The comedy of Richler’s previous novels is based on a cunning understanding of the sneaky motives of flunkies and upstarts. Perhaps his most brilliant set-piece is the chapter in St. Urbain’s Horseman describing a Sunday morning softball game on London’s Hampstead Heath, played by a cutthroat crew of show-biz expatriates (actors, producers, blacklisted writers). On the grass behind home plate gather their ex-wives, who cheer and heckle as their paunchy former hubbies pant around the bases. Unaffectionately known as the Alimony Gallery, these “crones” had stuck with their husbands through lean times only to be tossed aside for starlets and other “juicy little things.”

So there they were, out on the grass chasing fly balls on a Sunday morning, short men, overpaid and unprincipled, all well within the coronary and lung cancer belt, allowing themselves to look ridiculous in the hope of pleasing their new young wives and girlfriends…. Here was Al Levine, who had used to throw marbles under horses’ legs at demonstrations and now raced two horses of his own at Epsom. On the pitcher’s mound stood Gordie Kaufman, who had once carried a banner that read No Pasarán through the streets of Manhattan and now employed a man especially to keep Spaniards off the beach at his villa on Mallorca. And sweating under a catcher’s mask there was Moey Hanover, who had studied at a yeshiva, stood up to the committee, and was now on a sabbatical from Desilu.

Laughs aren’t entirely missing from Joshua Then and Now. There’s a funny account of the frolicsome activities of the William Lyon Mackenzie King Memorial Society—Mackenzie King was the barmy prime minister who worshiped his dead mother and communed with illustrious spirits (Louis Pasteur, Lorenzo de’ Medici)—and a funny line about a psychiatrist who pens a self-help book called Your Kind, My Kind, Mankind.

But the humor of Joshua Then and Now isn’t rooted in the grit and rue of rivalmanship, as it was in St. Urbain’s Horseman and Duddy Kravitz, both of which were Jewish-comic classics. The satire here is groggy and far-fetched—Mary Hartman surreal. Joshua’s mother, for example, is a red hot mama in spiked heels who does a burlesque bump-and-grind at his bar mitzvah. “Now I want everybody who got a hard-on watching my act to be a good boy and put up his hand,” she says at the finish. She later embarrasses Joshua by turning up in porn films giving blow jobs to men half her age, Canada’s answer to Georgina Spelvin. Her body exploited for lust and profit, the old bird falls in with a feminist cadre which uses her to represent The Degradation of Women.

Predictably, Richler’s feminists are little more than cartoon harpies: “truculent” fanatics with hairy armpits and fiery eyes. During a pro-abortion demonstration on Parliament Hill, Joshua’s mother startles her sisters and the media by whipping out a placard from under her poncho which reads:

SMELLY IT MAY BE

BUT MY CUNT BELONGS TO ME

Perhaps my sense of humor is on the blink, but I find such jokes desperately unfunny. Blind stabs in the dark.

Advertisement

Even more tiresome are the Archie Bunkerish monologues of Joshua’s father, Reuben, who in flashbacks explains passages from the Bible to his impudent son.

…This is the Bible we’re studying, it’s been translated into every language you ever heard of and has sold more copies than any book in the world. So pay attention. We are now talking about Persia during the days of King Ahasuerus, see. The king’s wife, a real bitch, was called Vashti, and one day the king calls for her, he was at this banquet with all his followers and maybe he feels like a piece of ass, and she wouldn’t come, which really burned him. He dumped her and got this idea to run a beauty contest, but only for broads who still had their cherry….

As this nightclub routine drones on, you can almost hear the scraping of chairs as customers groan, “Check, please.”

Yet Reuben’s exegetical rap on the Book of Esther perhaps holds the key to the novel. He asks young Josh what it means to have “a Mordecai at your gates,” adding that Mordecai is the man they’re supposed to honor at Purim. Mordecai, explains Reuben, is a “kvetchy Hebe” who sits at King Ahasuerus’s gate and refuses to bow his head. After he enters his uncle’s daughter Esther in the king’s so-called beauty contest, she ends up in the palace “screwing the royal head off every night.” After much intrigue and slaughter, Mordecai becomes prime minister. From the Book of Esther, Reuben draws two morals: “One, Mordecai’s rise out of nowhere proves something I’ve always tried to knock into your head. It doesn’t matter what you know, but who you know.” Two, “If I interpret the law correctly, you are not allowed to marry out of the faith unless it’s into a royal family. Interesting, eh?”

After all the fuming about West Indian studs and honor sullied at Ibiza, Ibiza—after trying to make our ribs ache with pained laughter—the novel ends with a scene of soft tender bliss. In the garden behind their house, a battered Joshua touches Pauline’s hair, then leans on her for support. As the two of them start inside, Reuben, watching from a jeep, thinks, Yeah, well, right. It’s a beautifully subdued fade-out—but it doesn’t wash away the spiteful bile that’s accumulated like sediment for more than 400 pages. For all its lurching ambition, Joshua Then and Now is finally a sentimental fable about a morose Jewish lump redeemed by the love of a royal shiksa. Love’s balm soothes all wounds, that’s the first lesson we are meant to get from the Book of Joshua. And the second?

Mordecai is still sitting at the gates. Kvetchy, unbowed.

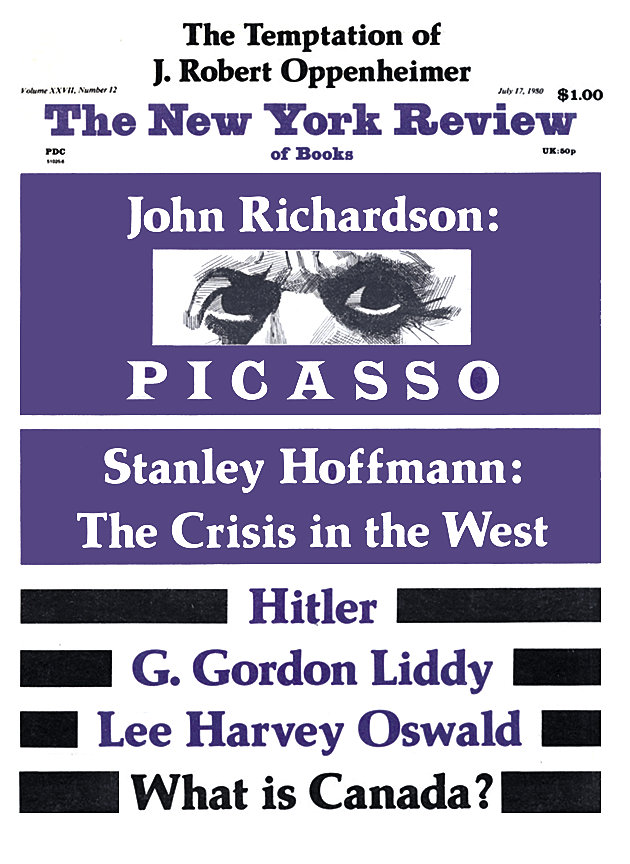

This Issue

July 17, 1980