P.D. James is a mystery writer who with her new book has abandoned mystery. She began as a writer of orthodox detective stories in the English tradition. Her first book, Cover Her Face, opened with a tea party, and offered fairly conventional characters in a rural setting. But this book and its immediate successors seem not to have satisfied her, and in Shroud For a Nightingale (1971) she used her professional knowledge as a hospital administrator to give a realistic portrait of the Nightingale Training College for Nurses. The Black Tower (1975) is set in a home for incurables, and the crime is investigated by a detective who has just been reprieved from what was in effect a death sentence, a diagnosis of leukemia.

The detective, Commander Adam Dalgleish, appears in her first seven books, but the portrait of him is deepened and strengthened in The Black Tower and in the following Death of an Expert Witness (1978). Yet although these later books are pushing to extend the bounds of the detective story, there is a puzzle to be solved and a murderer to be exposed in all of them. With Innocent Blood this apparatus has gone. There is the threat of violence, but no mystery. There is no Dalgleish. No doubt this is the serious novel that Phyllis James had it in mind to write when she began.

The germ of the plot lies in the British Children’s Act of 1975, which gave adopted children over the age of eighteen access to their birth records. It was opposed in advance both by natural parents, keen to preserve their anonymity, and by those who had adopted the children, although in fact it has been little used. In the book it is invoked by Philippa Palfrey, adopted daughter of modish sociologist Maurice (author of Schooled to Fail: Class Poverty and Education in Great Britain, etc.) and his dejected wife Hilda. Philippa learns that her real father raped a twelve-year-old schoolgirl, and her mother then strangled the girl. They were sentenced to life imprisonment. Her father died in prison, her mother Mary Ducton is due for release in a month’s time. Philippa sees her mother in prison, and after Mary’s release rents a flat which they share. In the meantime Norman Scase, father of the raped girl, is planning to kill the released murderess, partly as a duty, partly in accordance with a promise made to his wife when she was dying of cancer.

The plot has a melodramatic power, and it is perhaps this melodramatic quality that has made the book an immense commercial success. In the US film rights have been sold, reviews have tended to be long and enthusiastic, although in England the reception has been markedly cooler. Innocent Blood shows among other things the risks of too much ambition. The puzzle element in a crime story has been a crutch for many. Chandler, for example, found creating a puzzle a bore, but the necessary construction work proved a great help in making the stereotyped heroines of his early books acceptable. Throw away the crutch and you stand on your own two fictional legs, with the need to justify action by means of character, not of mystery. And judged by its characters, Innocent Blood is strikingly implausible.

First, Philippa. An ordinary girl of eighteen, on learning that her mother is a murderess, might feel that she did not want to renew the family connection. Philippa’s determination never falters, however, and in an attempt to make her very unlikely actions plausible, the author turns her from a human being into a quotation machine, a sure winner in any literary quiz. The first thing that comes to her mind on learning the appalling truth about her parents is a quotation from Bunyan. In a chat with her mother she quotes Heine’s last words, at other times she quotes Donne and L.P. Hartley to herself, and at another still “some words of William Blake fell into her mind.” Nor is her knowledge confined to literature. She is capable of making nice discriminations about eighteenth-century painting, and of distinguishing a trainee journalist from an experienced one almost at first glance. It is true that we have been told she is a clever girl, but she seems rather to be crammed with facts, facts which she is dismally eager to communicate.

Philippa’s mother also belongs more to literature than to life. Although no more than a hospital medical records clerk before her imprisonment, Mary Ducton is not fazed by the Heine quotation, and says things like “You must excuse me if I seem socially inept,” this acknowledgment of an ineptness hardly ever apparent being the only sign of her years in prison. This is indeed a highly literary novel, in which even a private detective employed by Scase quotes Thomas Mann. What would mother and daughter have talked about if Mary, as seems more probable, had been an ordinary woman damaged or brutalized by prison life, not interested in visiting the Brompton Oratory to see the Mazzuoli marbles?

Advertisement

It is because the loving relationship between Philippa and her mother is essential to the plot that it is—not very skillfully—forced on us. In such a book too we must be sympathetic to the central characters, and for this reason the actual crime is greatly softened, at least in Mary’s telling. Her husband was gentle and timid, not sadistic. “It was a technical rape, but he wasn’t violent.” And when Mary came home and learned what had happened, she did not mean to strangle the child but only to stop her crying. This seems a kind of copout, making it easier for Philippa to love her mother.

The improbability of the plot (with which the story’s unexpected final turn is quite in keeping) is to some extent concealed by the intelligence and detailed realism of the writing. “In these easy chairs no visitor had ever sat at ease,” we are told on the second page when Philippa is being given details by a social worker of the application form on which she should apply for her birth certificate. Here, as in her detective stories, P.D. James’s writing has a solid stylishness touched by flashes of wit and observation. An obsessive quality in Philippa’s adoptive mother, Hilda, is expressed in our first sight of her, cooking “with a peculiar intensity, moving like a high priestess among the impedimenta of her craft, consulting her recipe book with the keen unblinking scrutiny of an artist examining his model.” We learn something about the nature of Maurice, the adoptive father, from a detailed description of the things in his entrance hall, the Staffordshire figures of Nelson and Wellington and the three nineteenth-century Japanese prints above them. Maurice is not just a sociologist, but one with a touch of the aesthete.

We learn something about the author, too, when she names the three Japanese artists and tells us that the picture frames are of curved rosewood. She is a writer remarkably concerned with the details of things and places. The flat Philippa rents to occupy with her mother gets several pages of description, the room rented by Scase in a hotel is given a page, and so is the visiting room in prison. Often the details are strongly visual, giving us in Scase’s hotel room the stained fawn carpet, a spot of dampness in one corner, the rickety wardrobe, and the dressing table “in veneered walnut with a spotted mirror.” In the prison visiting room there is a print of Constable’s Hay Wain, artificial flowers, a small octagonal table separating two facing chairs. Such elaborate descriptive detail has always been one of P.D. James’s strengths. Through it she often succeeds in giving us the feeling of a house or a community, and of the people in it. The visiting room inhibits Philippa and her mother so that they have to get out into the grounds. Scase occupies his hotel room with a purpose, but it expresses the dingy anonymity of his personality.

The book also attempts to get the feeling of contemporary London, chiefly through a concern with ways of traveling in it by public transport, especially by Underground. “She changed at Oxford Circus and he followed her on the long track [sic—trek] to the northbound Bakerloo line”; “Victoria was out…. Similarly, he could eliminate South Kensington and Gloucester Road, since both were on the Piccadilly line”; “The quicker way to Liverpool Street Station and the eastern suburban line was by Waterloo and the City line.” We are told, and believe, that the York to London trains go from platform eight. This immense accumulation of factual detail certainly gives us something, although it’s hard to be quite sure what. Although it helps to make the localities convincing, it does nothing for the people in them. The characters with whom the author is less involved, like Maurice and Hilda, are much more plausible than Philippa, her mother, and the unlikely avenger Scase. Nor do the settings help the plot, which is made more jarringly melodramatic by the solidity of rooms and furniture. There is no doubt about P.D. James’s talent, but on the evidence of Innocent Blood one must hope for the return of Adam Dalgleish in her next book.

Few writers could be more technically dissimilar than P.D. James and Beryl Bainbridge. Where James is counting the buttons on the Victorian chaise longue, Bainbridge often doesn’t even bother to mention that the living room contains any furniture at all. Where James feels it necessary to document every background with care, Bainbridge in Another Part of the Wood does not bother to tell us more about the central figure Joseph than that he is an administrator at a technical college. The glancing indirection of Beryl Bainbridge’s writing, its waywardness and humor, owes something to Firbank and, further back, to Sterne, but she is a genuine original, with a macabre imagination and a wonderful gift for catching tones of speech, whether the people talking are the creepy little girls of Harriet Said…, the besotted young woman and her lover in Sweet William, or heavyweight Freda and lean Brenda in The Bottle Factory Outing. Nobody else is so dashingly offhand in telling us only what she feels we need to know for the purposes of her story, or is able to mix comedy and horror with such assurance.

Advertisement

A reading of Bainbridge’s work might begin with Harriet Said…(1972), her first written but third published novel, which was turned down several times, and continue with The Bottle Factory Outing (1974). The adroit plotting of the first book places the suppressed lesbian relationship of two schoolgirls in the foreground of the story while making us uneasily aware of some mysterious nastiness that is not revealed until the end. A similar uneasiness broods over The Bottle Factory Outing. When Freda, the comely but hefty romantic, is thinking longingly about her assignation with Vittorio from the bottle factory where she works with Brenda, her mind moves from delicious sexual fantasy (“I will be one of those women…painted naked on ceilings, lolling amidst rosecoloured clouds”) to an image of reality, Brenda in the factory cellar, cobwebs lacing her hair as she tries to escape the pawing of Rossi the manager. Both books end in violence, both contain an element of mystery. Yet the violence has its seeds in scenes that are comic or even farcical, and although The Bottle Factory Outing contains a murder that remains unexplained until the last pages, Beryl Bainbridge’s concerns are not those of the crime writer.

Her world is one in which it is the role of men to demand and exploit, of women to give and console. When Ann in Sweet William (1975) meets the eponymous William McClusky she feels so weak with unrecognized sexual yearning that she thinks she has influenza. In a succession of brilliant comic scenes Ann succumbs to William, shares her flat with him, learns that he has not only a wife but several mistresses including her cousin, becomes pregnant, and bears his child. On the last page, having helped to deliver the baby, William is off again. “‘He’s bloody well gone,’ said Mrs. Kershaw.” The plot could provide material for a thesis on women as victims, but for Bainbridge this is simply the way of the world. It is the way of men like sweet William to charm and impregnate and console, and then go off with another girl or boy friend. (William is last seen in the company of Chuck van Schreiber, who is putting up the cash for his neo-Pinterian play.) Women may be jealous or miserable, but for the most part happily fulfill their function, which is to lie back and enjoy it, then to bear children, and above all to be tolerant. For such as William, in dreams begin no responsibilities.

Another Part of the Wood is one of the least successful of Bainbridge’s novels. It appeared in 1968, her second published book, and in spite of some rewriting for this edition has an air of contrivance uncharacteristic of her best work, which flows with deceptive casualness. A group of people are gathered together at a very small holiday camp in Wales. The camp is no more than a few huts run by a local family, and the group includes Joseph, the divorced technical administrator, his girl friend, his young son by his wife, and the oversized, slightly retarded youth Kidney. A couple of friends, plus George who runs the camp with his week-end helper Balfour, make up the cast. Short, impressionistic scenes give the feelings of one member of the party after another, revealing failures of understanding, disconnections of feeling, general imperceptiveness, and egoism. The tragedy that provides the book’s climax not unexpectedly involves Kidney.

It would seem that at this time Beryl Bainbridge was looking for an approach that would give scope to the juxtaposition of zany comedy and horror that she used so effectively later on. Most of her people seem odd only because she shows them to us through a distorting lens. In this novel, however, Balfour’s fits, Kidney’s incomprehension, George’s moroseness give an effect of caricature, and the dialogue tends toward a solemnity that doesn’t suit a writer who best conveys seriousness through frivolity. “In proper planning they’d know that people need to be in a community,” Joseph says in a post-dinner discussion round the hut table. “They’d know that ugly surroundings imprison a man and that beauty liberates him. They’d use colours and play areas.” In later novels people may talk in clichés like these, but the phrases will be treated with the deflating touch of irony that is absent here.

The book’s chief interest, however, still lies in the portrait of Joseph, who is always intending to do things that he never manages, like taking his young son up the nearby mountain. Joseph is capable of good-natured actions but can’t sustain them, as we see in his befriending and subsequent neglect of Kidney. He is a preliminary sketch for sweet William, and the extent to which Beryl Bainbridge’s art has developed in subtlety can be seen by comparing the two. There is not much to be said for either of them, as father or as lover, and this is made much too plain in the case of Joseph, so that we can hardly fail to dislike him. Sweet William’s is a much more subtle portrait, of a man capable of charming any woman into bed.

Beryl Bainbridge is one of the half-dozen most inventive and interesting novelists working in Britain today, and virtually anything she writes is worth reading. It would be a pity, though, to come to her novels first through an early book like Another Part of the Wood.

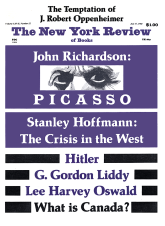

This Issue

July 17, 1980