I

Writers have had an up and down time in the courts recently. The press is worried about a series of new judicial decisions that it believes will sharply decrease its powers and shrink the role of the First Amendment in American society. The latest of these is the amazing case of US v. Snepp, in which the Supreme Court ordered an author to turn over all his profits to the government without even holding a hearing on the issue. But the press has also won what it regards as important victories. The most recent of these is the Richmond Newspapers case, decided only a few months ago, in which the Court reversed its decision in an earlier case and held that reporters, at least in principle, have a right to attend criminal trials even when the defendant wishes to exclude them.1

US v. Snepp is much the more important of the two cases. Frank Snepp signed a contract when he joined the CIA, promising to submit to it, before publication, anything he later wrote about it. The CIA argues that that agreement, which it obtains from every agent, is necessary so that it can make its own judgment, in advance, about whether any of the material an author proposes to publish is classified, and take legal action to enjoin what it does consider classified if the author does not accept its judgment. Snepp wrote a book called Decent Interval, after leaving the agency, in which he sharply criticized the CIA’s behavior in Vietnam during the final months of the war. He feared that the agency would use its right to review his manuscript to delay and harass him by claiming that matters of no importance to security were classified, as the agency had certainly done in the case of Victor Marchetti, another former agent who had written and submitted a book.2 After much indecision Snepp decided to publish his book without submitting it to the CIA first.

The agency sued him under the contract. Snepp argued that the First Amendment made his contractual agreement null and void because it was a form of censorship. But neither the federal district court nor the Circuit Court of Appeals, to which Snepp appealed, accepted that claim. The district court ordered Snepp, by way of remedy, to hand over to the government all his profits on the book—his only earnings for several years of work—but the Circuit Court did reverse the district court on this point. It said that the government must be content with such actual financial damages as it could prove it suffered because Snepp had broken his contract, which is the normal remedy in breach of contract cases.

Snepp appealed to the Supreme Court on the First Amendment point. The government asked the Court not to take the case for review, and said that it was satisfied under the circumstances with the damage remedy the Circuit Court had ordered. But it added that if the Court did take the case, it would like the opportunity to argue that the Court should reinstate the district court’s much more onerous remedy. In the end the Court did accept the case, against the government’s wishes, but, as it turned out, only for the purpose of reinstating the harsher penalty. The Court did that, contrary to all traditions of judicial fairness, without offering opportunity for argument to anyone. A court that is supposedly dominated by the ideal of judicial restraint twisted principles of procedural fairness to reach a result for which no party had asked.

Some journalists speculate that the Court is furious with the press over The Brethren, Woodward and Armstrong’s “inside story” of the Court published last year, and took this opportunity for revenge. But many First Amendment lawyers take the more worrying view that the case is only the latest and most dramatic example of the decline of free speech in the United States.

It is worth describing the evidence for this gloomy opinion in some detail. No leading constitutional lawyer (except Mr. Justice Black) has ever thought that the First Amendment bars the government from any conceivable regulation of speech. It has always been possible for people to sue one another in American courts for libel and slander, for example, and even the most famous defenders of free speech have conceded that no one has a constitutional right to cry “fire” in a crowded theater or publish information about troop movements in time of war. Nevertheless there have been tides in the Court’s concern for speech as against other interests, and the present moment strikes many commentators as very low tide indeed.

The Warren Court moved very far, for example, toward protecting pornography from the censor, on the ground that it is not part of the state’s concern to decide what people, in private, should or should not find tasteless or embarrassing. But the Burger Court endorsed the idea of censorship in accordance with local standards of decency, and though this test has posed no problems for the pornographers of Times Square it has made many movie theaters in small towns very cautious indeed. Defamation suits brought by public figures against newspapers provide another example. The Warren Court, in its famous decision in Times v. Sullivan, held that a public figure could not sue a paper for libel even if what that paper had published was both false and damaging, unless the public figure succeeded in showing that the paper had been not merely wrong but either malicious or reckless in what it published. The Court held that public figures must be supposed to have waived their common law right to sue for ordinary misrepresentation.

Advertisement

The Burger Court has not overruled the Sullivan decision, but it has narrowed the class of people who count as public figures for this purpose, and in the recent case of Herbert v. Landau it held that even when a public figure sues, reporters may be examined, under oath, about their methods of investigation and editorial judgment, in an effort to show their malice or recklessness. The Court rejected the protests of newspapers and networks that the threat of such examinations, in which reporters would be forced to defend largely subjective judgments, would inhibit reporters’ freedom of inquiry and so make them less effective servants of the public.

Two of the most important recent judicial decisions involving First Amendment claims never reached the Supreme Court. The first of these was the much publicized case of the New York Times reporter Myron Farber, which I discussed some time ago in these pages.3 The New Jersey courts held that Farber could be jailed for contempt because he refused to turn over his files, which might well have contained information useful to a defendant accused of murder, to defense attorneys. The Times (supported by other papers) argued that unless reporters are able to promise confidentiality to informers, for example, their sources will disappear and the public will lose an important source of its information. But the courts did not accept that argument.4

The second was the case of The Progressive, which ended in comedy, but was nevertheless the occasion for the first preliminary injunction ever granted in the United States against publication in advance. That magazine proposed to publish an article entitled “The H-Bomb Secret: How We Got it—Why We’re Telling It,” and submitted it to the Atomic Energy Commission for informal clearance. The author had in fact used only public and legally available information. But the Commission, relying on its claim that all information relating to atomic weapons is “born classified” under the Atomic Energy Act, and cannot be published unless it is affirmatively cleared for publication by the Commission, refused to pass the article and sued to enjoin it. The Commission persuaded a district court judge, who listened to government testimony in secret, that publication would be damaging to national security, because it might enable a smaller nation (Idi Amin’s Uganda was the example of the day) to construct a hydrogen bomb.

The Progressive appealed the district court’s injunction to the Circuit Court, but before that Court acted it became apparent that all the information the author used was in fact available at a public library maintained by the Commission, and several newspapers then published the contents of the proposed article without seeking clearance. The government withdrew in some embarrassment, and The Progressive’s article was finally published. Nevertheless it was ominous that the First Amendment provided so little protection in this case. The Commission’s “born classified” argument—that it is illegal to publish any information about atomic weapons that it has not specifically cleared—is absurdly overbroad, and would not have been sustained, I think, by higher courts. But the courts might well have sustained a procedure that allows a judge to decide particular censorship cases in secret proceedings where the judge may be unduly impressed by government technical “experts.” The Atomic Age is not a healthy environment for free speech.

Not all the evidence of the present decline of free speech is drawn from judicial decisions. The Freedom of Information Act, which was strengthened by Congress after the Watergate scandal, provides that anyone can obtain any information in the hands of the federal government, with certain exceptions to protect personal privacy, trade secrets, national security, and the like. We owe much valuable information—for example, parts of William Shawcross’s book on Cambodia—to that Act. But pressure has been building for substantial amendment. Doctors point out that double-blind experiments testing new drugs and procedures are ruined when reporters discover information that destroys the confidentiality that makes the experiments statistically significant. Scientists argue that the incentive to carry on research may be jeopardized when newspapers publish details of interesting grant applications. The National Disease Control Center finds that hospitals will not seek its aid in locating hospital infections when journalists can make the Center’s reports to the hospitals available to potential litigants.

Advertisement

The CIA already benefits from a specific exception to the Freedom of Information Act allowing it to withhold information on grounds of national security. It now seeks much more confidentiality—and, in the atmosphere of concern for better intelligence that has followed the seizure of the American embassy in Iran, it may get it. The Justice Department, for example, is sponsoring an amendment (HR 7056) that would exempt from the Act whatever the CIA deems to be information obtained from nongovernment sources, or information that tends to identify intelligence sources, or information concerning intelligence-collecting systems. The proposed amendment expressly provides that the CIA’s decisions to withhold information by declaring that it belongs to one of these categories will not be reviewable in any court. So far, however, the Senate committee concerned with the CIA has resisted such restrictions.

Congress is now moving toward passage, however, of a new bill that would make it a crime for a former CIA agent or anyone else to publish the name of a present agent. The Senate version, as amended in the Intelligence Committee, now provides that those other than present or former agents who publish names are not liable unless they do so as part of a “pattern or practice” of such disclosure. The report of that committee indicates that this qualification is to protect “mainline journalists.” But the qualification is so vague as to offer little protection indeed, and the bill, if constitutional, would surely constrain journalists’ investigation of the agency.

The press has not, as I said, lost all its battles. The Burger Court unanimously rejected the Nixon administration’s attempt to prevent the publication of the Pentagon Papers, and has just affirmed, in the Richmond Newspapers case, that the press does have some constitutionally protected position under the First Amendment, strong enough so that a trial judge must show some special reason for excluding reporters from a criminal trial. But the press nevertheless believes that it is losing ground overall.

II

Nat Hentoff, in his comprehensive book on the history of the First Amendment,5 describes the rise of the idea of free speech and a free press in America from Peter Zenger on, and notices, in apparent sadness, the symptoms of what he plainly takes to be its present slump. The book is remarkably readable and broad. It has the great merit of showing how the idea of free speech takes on different content as the underlying substantive issues change from educational policy to obscenity to reporting of criminal trials. The tone of the book seems dispassionate. Hentoff argues mostly by quoting others. But there is no doubt where he stands. He is a partisan of free speech, and in this book there are victories and defeats for freedom, heroes and cowards of the press, friends and enemies of liberty.

But there is not much attempt at analysis of the philosophical grounds of free speech or freedom of the press, or much effort to find the limits of the freedoms and powers Hentoff wants to defend. In this respect he is typical of journalists who complain about the fate of the First Amendment in the courts, though he writes better and with more enthusiasm and knowledge than most. The press takes the Amendment as a kind of private charter, and attacks more or less automatically every refusal of the courts to find some further protection in that charter. The newspapers and networks denounced the decisions in the Farber and Herbert cases as fiercely—indeed even more fiercely—than those in the cases of The Progressive and Snepp.

But this strategy of automatic appeal to the First Amendment is, I think, a poor strategy, even if the press is concerned only to expand its legal powers as far as possible. For if the idea becomes popular that the Amendment is an all-purpose shield for journalists, warding off libel suits, depositions, and searches as well as censorship, then it must become a weaker shield, because it will seem obvious that so broad a power in the press must be balanced against other private and social interests in the community. What will then suffer is the historically central function of the First Amendment, which is simply to ensure that those who wish to speak on matters of political and social controversy are free to do so. Perhaps the surprising weakness of the First Amendment in protecting the defendants in The Progressive and Snepp cases, for example, is partly a consequence of the very effectiveness of the press in persuading the courts, in an earlier day, that the power of the First Amendment extends well beyond straight censorship cases.

In order to test this suspicion, we must consider an issue that Hentoff and other friends of the First Amendment neglect. What is the First Amendment for? Whom is it meant to protect? A variety of views is possible. The dominant theory among American constitutional lawyers assumes that the constitutional rights of free speech—including free press which, in the constitutional language, means published speech in general rather than journalists in particular—are directed at protecting the audience. They protect, that is, not the speaker or writer himself but the audience he wishes to address. On this view journalists and other writers are protected from censorship in order that the public at large may have access to the information it needs to vote and conduct its affairs intelligently.

In his famous essay On Liberty, John Stuart Mill offered a similar but more fundamental justification for the right of free speech. He said that if everyone is free to advance any theory of private or public morality, no matter how absurd or unpopular, truth is more likely to emerge from the resulting market-place of ideas, and the community as a whole will be better off than it would be if unpopular ideas were censored. Once again, on this account, particular individuals are allowed to speak in order that the community they address may benefit in the long run.

But other theories of free speech—in the broad sense including free press—hold that the right is directed at the protection of the speaker, that is, that individuals have the right to speak, not in order that others benefit, but because they would themselves suffer some unacceptable injury or insult if censored. Anyone who holds this theory must, of course, show why censorship is a more serious injury than other forms of regulation. He must show why someone who is forbidden to speak his mind on politics suffers harm that is graver than when he is forbidden, for example, to drive at high speeds or trespass on others’ property or combine to restrain trade.

Different theories might be proposed: that censorship is degrading because it suggests that the speaker or writer is not worthy of equal concern as a citizen, or that his ideas are not worthy of equal respect; that censorship is insulting because it denies the speaker an equal voice in politics and therefore denies his standing as a free and equal citizen; or that censorship is grave because it inhibits an individual’s development of his own personality and integrity. Mill makes something like this last claim in On Liberty, in addition to his market-place-of-ideas argument, and so his theory can be said to be concerned to protect the speaker as well as the audience.

Theories concerned to protect the audience generally make what I have called an argument of policy for free speech and a free press.6 They argue, that is, that a reporter must have certain powers, not because he or anyone else is entitled to any special protection, but in order to secure some general benefit to the community as a whole, just as farmers must sometimes have certain subsidies, not for their own sakes, but also to secure some benefit for the community. Theories concerned to protect the speaker, on the other hand, make arguments of principle for free speech. They argue that the speaker’s special position, as someone wanting to express his convictions on matters of political or social importance, entitles him, in fairness, to special consideration, even though the community as a whole may suffer from allowing him to speak. So the contrast is great: in the former case the community’s welfare provides the ground for the protection, but in the latter the community’s welfare is disregarded in order to provide it.

The distinction is relevant to the present discussion in many ways. If free speech is justified on grounds of policy, then it is plausible that journalists should be given special privileges and powers not available to ordinary citizens, because they have a special and indeed indispensable function in providing information to the public at large. But if free speech is justified on principle, then it would be outrageous to suppose that journalists should have special protection not available to others, because that would claim that they are, as individuals, more important or worthier of more concern than others.

Since the powers the press claims, like the power to attend criminal trials, must be special to it, it is natural that the press favors a view of free speech based on the policy argument concerned to protect the audience: that the press is essential to an informed public. But there is a corresponding danger in this account. If free speech is justified as a matter of policy, then whenever a decision is to be made about whether free speech requires some further exception or privilege, competing dimensions of the public’s interest must be balanced against its interest in information.

Suppose the question arises, for example, whether the Freedom of Information Act should be amended so that the Disease Control Center is not required to make its reports available to reporters, or whether the Atomic Energy Commission should be allowed to enjoin a magazine from publishing an article that might make atomic information more readily available to foreign powers. The public’s general interest in being well informed argues against confidentiality and for publication in both cases. But the public also has an interest in infection-free hospitals and in atomic security, and these two kinds of interests must be balanced, as in a cost-benefit analysis, in order to determine where the public’s overall interest lies. Suppose that in the long term (and taking side effects into account) the public would lose more overall if the information in question were published. Then it would be self-contradictory to argue that it must be published in the public’s interest, and the argument for free speech, on grounds of policy, would be defeated.

The problem is quite different, of course, if we take free speech to be a matter of principle instead. For now any conflict between free speech and the public’s welfare is not a pseudo conflict between two aspects of the public’s interest that may be dissolved in some judgment of its overall interest. It is a genuine conflict between the rights of a particular speaker as an individual and the competing interests of the community as a whole. Unless that competing interest is very great—unless publication threatens some emergency or other grave risk—the individual’s right must outweigh the social interest, because that is what it means to suppose that he has this sort of right.

So it is important to decide, when the press claims some special privilege or protection, whether that claim is based on policy or principle. The importance of the distinction is sometimes obscured, however, by a newly fashionable idea, which is that the public has what is called a “right to know” the information that reporters might collect. If that means simply that the public has an interest in knowledge—that the community is better off, all things being equal, if it knows more rather than less about, say, criminal trials or grant applications or atomic secrets—then the phrase is simply another way of stating the familiar argument of policy in favor of a free and powerful press: a better informed public will result in a better society generally. But the suggestion that the public has a right to know suggests something stronger than that, which is that there is an audience-protective argument of principle in favor of any privilege that improves the press’s ability to gather news.

But that stronger suggestion is, in fact, deeply misleading. It is wrong to suppose that individual members of the community have, in any strong sense, a right to learn what reporters might wish to discover. No citizen’s equality or independence or integrity would have been denied had Farber, for example, chosen not to write any of his New York Times stories about Dr. Jascalevich, and no citizen could have sued Farber requiring him to do so, or seeking damages for his failure to write. It may be that the average citizen would have been worse off if the stories had not been written, but that is a matter of the general welfare, not of any individual right.

In any case the alleged right to know is supposed to be a right, not of any individual citizen, but of the public as a whole. That is almost incoherent, because “the public,” in this context, is only another name for the community as a whole. And it is bizarre to say that even if the community, acting through its legislators, wishes to amend the Freedom of Information Act to exempt preliminary reports of medical research, because it believes that the integrity of such research is more important than the information it gives up, it must not do so because of its own right to have that information. Analysis of First Amendment issues would be much improved if the public’s interest in information, which might well be out-balanced by its interest in secrecy, were not mislabeled a “right” to know.

It is now perhaps clearer why I believe that the press’s strategy of expanding the scope of the First Amendment is a bad strategy. There is always a great risk that the courts—and the legal profession generally—will settle on one theory of a particular constitutional provision. If First Amendment protection is limited to the principle that no one who wishes to speak out on matters or in ways he deems important may be censored, then the single theory of the First Amendment will be a theory of individual rights. And this means that the commands of free speech cannot be out-balanced by some argument that the public interest is better served by censorship or regulation on some particular occasion.

But if the Amendment’s protection is claimed when the claim must be based on some argument concerned to protect the audience—if it is said that reporters must not be examined about their editorial judgment in libel actions because they will then be less effective in gathering news for the public to read—the single theory that might justify so broad an Amendment must be a theory of policy. It is not surprising that the dissenting opinions in the cases about which the press complains—the opinions that argue that the press should have had what it asked—contain many arguments of policy but few arguments of principle. In the Herbert case, for example, Mr. Justice Brennan based his dissenting opinion on a theory of the First Amendment strikingly like Mill’s theory concerned to protect the audience. Brennan cited the following well-known remark of Zechariah Chafee: “The First Amendment protects…a social interest in the attainment of truth, so that the country may not only adopt the wisest course of action, but carry it out in the wisest way….”

But of course these appeals to the general welfare of the public invite the reply that in some cases the public’s real interest would be better served, on balance, by censorship than by publication. By contrast, if the Amendment is limited to its core protection of the speaker, it can provide, in its appeal to individual rights rather than the general welfare, a principle of law strong enough to provide important protection in a true First Amendment case, like that of The Progressive. But if the Amendment becomes too broad it can be defended only on grounds of policy like those Brennan provided. It can be defended, that is, only on grounds that leave it most vulnerable just when it is most necessary.

III

If we attend only to the core of the First Amendment, which protects the speaker as a matter of principle, then the recent record of the Court and Congress looks better, though far from perfect. Before the Snepp case, that core of principle was threatened, even arguably, only by the obscenity decisions, about which most of the press cares very little, and in the case of The Progressive, which was only a district court decision, and which ended in victory for the press anyway. The other decisions that so angered journalists—like the Farber and Herbert cases—were all decisions that simply refused to recognize reporters’ arguments of policy that the public would generally be better off if reporters had special privileges. The chilling effect the press predicted for these decisions has not materialized—indeed Mike Wallace, one of the reporters who resisted examination in the Herbert case, recently said that the press might have deserved to lose that case.

In any event, if democracy works with even rough efficiency, and if the reporters’ arguments of policy are sound, then they will gain the powers they seek through the political process in the long run anyway, and so they have lost nothing of lasting importance by being denied these powers in the courts. For if the public really is generally better off when the press is powerful, the public might be expected to realize where its self-interest lies sooner or later—perhaps aided by the press’s own advice. Except in cases like the Farber case, when the rights of individuals—in that case the right to a fair trial—would be infringed by expanding the power of the press, the public can then give the press what it wants by legislation.

The question arises, however, whether the Richmond Newspapers decision (in which, as I said, the Supreme Court held that in the absence of strong countervailing interests reporters have a right to attend criminal trials) shows that the Court is now committed to a theory of the First Amendment that goes beyond the core of principle and extends to the protection of the general welfare of the audience. It is certainly true that the result in that case might be justified by an argument of policy like the argument Brennan made in the Herbert case. Burger’s opinion in the Richmond Newspapers case points out, for example, that the public is better off if its deep interest in the criminal process, and even its inevitable desire for retribution, is served by newspaper accounts of trials. But a careful reading of the several opinions in the case shows that though the seven justices who voted for the press (Mr. Justice Rehnquist dissented and Mr. Justice Powell took no part in the case) proceeded on somewhat different theories, two arguments were dominant, neither of which was a straightforward argument of policy of the type advanced by Mill.

The first, emphasized especially by Burger and, apparently, by Blackmun, ties the protection of the First Amendment to history. It argues that if any important process of government has been open to the public by longstanding traditions of Anglo-American jurisprudence, then citizens have a right, secured by the First Amendment, to information about that process, and the press therefore has a derivative right to secure and provide that information. The citizens’ right is not absolute, because it must yield before competing rights of the defendant, for example. But it stands in a case, like the Richmond Newspapers case, in which either no important interests of the defendant are in play, or the court can protect these interests by means other than barring reporters.

This argument from history seems to me a weak argument, for there is no reason why custom should ripen into a right unless there is some independent argument of principle why people have a right to what custom gives them. But it is in any case not an argument that requires the courts to decide whether the general welfare is, on balance, served by denying the press access to information or otherwise chilling speech on any particular occasion. It holds that the press must be admitted unless some special reason, and not simply the balance of general welfare, argues against it.

The second argument, stressed particularly in Brennan’s opinion, is both more important and more complex. It urges that some special protection for the press is necessary in order not simply to advance the general good but to preserve the very structure of democracy. Madison’s classic statement of this argument is often cited in the briefs the press submits in constitutional cases. He said that “a popular government, without popular information or the means of acquiring it, is but a prologue to a farce or a tragedy; or perhaps both…a people who mean to be their own governors, must arm themselves with the power knowledge gives.”

This is not Mill’s argument, that the more information people have the more likely they are to secure, overall, what they most want. It is rather the argument that the people need some information in order even to be able to form conceptions of what they want, and in order to participate as equals in the process of governing themselves. Mill’s policy argument is open-ended: the more information the better. But the Madisonian argument from the structure of democracy cannot be open-ended, for then it will end in paradox and self-contradiction.

That is so because every extension of the First Amendment is, from the stand-point of democracy, a double-edged sword. It enhances democracy because public information increases the general power of the public. But it also contracts democracy because any constitutional right disables the popularly elected legislature from enacting some legislation it might otherwise wish to enact, and this decreases the general power of the public. Democracy implies that the majority has the power to govern effectively in what it takes to be the general interest. If so, then any extension of constitutional protection of speech and the press will both increase and decrease that power, in these two different ways. Any particular person may be more effective politically because he will know more about, for example, atomic energy installations. But he may also be less effective politically, because he will lose the power to elect congressmen who will vote for censorship of atomic information. He may well count this trade-off, on balance, a loss in political power overall, particularly if he himself would prefer to sacrifice knowledge of atomic information in order to have the increased security that comes from no one else having that information either.

Every decision about censorship confronts each citizen with that sort of cost-benefit issue, and it cannot be said that he inevitably gains in political power when the matter is taken out of politics and decided by the Supreme Court instead. Indeed it is tempting to argue, on the contrary, that genuine, full-blooded democracy would require no First Amendment at all, for then every single issue of censorship would be decided by majority will through Congress and the state legislatures. But that goes too far, because, as Madison warned, people need some general and protected structure of public information even intelligently to decide whether they want more of it. There is no democracy among slaves who could seize power if they only knew how.

The opposite mistake is just as serious, however, because it is absurd to suppose that the American electorate, which already has access to a great deal more, and more sophisticated, public information than it shows any disposition to use, would gain in democratic power if the Supreme Court decided, for example, that Congress could not amend the Freedom of Information Act so as to exempt Disease Control Center reports, no matter how many people thought that such an exemption was a good idea. So the argument from the structure of democracy requires, by its own internal logic, some threshold line to be drawn between interpretations of the First Amendment that would protect and those that would invade democracy.

There is one evident, if difficult, way to draw that threshold line. It requires the Supreme Court to describe, in at least general terms, what manner of invasion of the powers of the press would so constrict the flow of information to the public as to leave the public unable intelligently to decide whether to overturn that limitation of the press by further legislation. The Court might decide, for example, that a general and arbitrary refusal of some agency of government to provide any information or opportunity for investigation to the press at all, so as to leave the public wholly uninformed whether the practices of that agency required further investigation, fell on the wrong side of that threshold.7 But it is extremely implausible to suppose that the public would be disabled in this dramatic way if the press were excluded from those few criminal trials in which the defendant requested such exclusion, the prosecution agreed to it, and the judge thought the interests of justice would on balance be served by it. The public of a state that adopted that practice would remain competent to decide whether it disapproved that arrangement and, if so, to outlaw it through the political process. So if Madison’s argument from the structure of democracy is applied to particular cases through the idea of a threshold of public competence, the Richmond Newspapers case should have been decided the other way.

There is another way to apply the argument from structure however, and this is suggested in Brennan’s opinion in that case. He said that though the press should have full access to information in principle, some line needed to be drawn in practice, and he proposed to draw the line, not through a threshold of the sort just discussed, but through balancing the facts of each individual case. He would assume, that is, that any constraint on the press’s access to information is unconstitutional, unless there are competing interests justifying that constraint, in which case the question would be which set of interests—the public’s interest in information or the competing interests—were of greater weight. In the Richmond Newspapers case he found no such competing interests at all, and therefore found it unnecessary to discuss how much the structure of democracy would be damaged by the exclusion in question.

All this brings Brennan’s argument from structure dangerously close to an argument of policy of the kind made by Mill. Though Brennan has himself been one of the most passionate advocates of free speech, his argument invites censorship in those cases in which the general welfare, on balance, would benefit from it, or rather when the public thinks that it would. For the balance Brennan describes could fall against rather than for The Progressive, for example. It is not absurd to suppose that publication of atomic data increases public risk to some degree. But it is absurd to think that a constraint on such publication, considered in itself as Brennan recommends, would impair the structure of American democracy to any noticeable degree, or leave the public, which has considerable general knowledge of atomic dangers, unable to decide whether to change its mind and remove the constraint through ordinary political action. Brennan would himself distinguish between cases concerning access to information, like the Richmond Newspapers case, and cases of straight censorship, like the Progressive case. But the theory he described to cover the former cases might all too easily develop into a general structural theory of the First Amendment, and freedom would then suffer.

IV

The Supreme Court’s procedures in Frank Snepp’s case were extraordinary and indefensible. But the decision was also, I think, wrong on the merits, and not simply as a matter of procedure and remedy. We may, for purposes of isolating the precise constitutional issue in question, suppose the following facts, some of which I stated earlier. When Snepp joined the CIA he signed a contract calling upon him to submit for clearance any materials he might later publish about the agency. He would not have been offered the position had he refused to sign that agreement. Decent Interval, the book he ultimately published without submitting it, contained no classified information. If he had never worked for the CIA and had never signed such an agreement, he would have been free to publish a book containing the same information without prior clearance, and he would have been subject to no legal penalty whatever. Indeed, if Congress passed a law requiring authors of books about the CIA to submit manuscripts to that agency for advance clearance, that law would be unconstitutional because it would violate authors’ First Amendment rights.8

So the question is this: When Snepp joined the CIA, and signed the agreement, did he waive his constitutional rights to publish unclassified information about the agency, a right that anyone else, not in his position, would plainly have? I put the question that way to show that one of the arguments the CIA pressed against Snepp is not in point. The agency argued that the requirement of prior clearance it imposed on him by contract did him no harm. If the review disclosed that he wished to publish classified information, then the agency would indeed act to prevent that. But Snepp, as the CIA rightly claimed, has no constitutional rights to publish classified information. He remained free to publish any nonclassified information once the review was completed, just as anyone else would be free to do. The contractual requirement of clearance (the CIA argues) merely gave the agency a legitimate opportunity to assess for itself whether the material proposed to be published was classified, and to take any steps to deter publication of any that was. So the contract was not a waiver of any constitutional right.

But if (as I assume) even Congress could not require those who had no connection with the CIA to submit manuscripts about it for prior review, then it is not open to the agency to argue that prior review has nothing to do with censorship. Victor Marchetti’s experience with the CIA after he submitted his manuscript shows (if any demonstration were needed) how a requirement of prior review makes what an author may say a matter of compromise, negotiation, and delay, all under the shadow of the threat of litigation, rather than a matter of what the author wants to say, which the First Amendment insists it should be.9

So the question is simply whether Snepp waived whatever First Amendment rights he would otherwise have had. Once again everything depends on what view one takes of the point and force of the right of free speech. Snepp’s lawyers argued, in his petition for rehearing in the Supreme Court, that “the unreviewed memoirs of former government officials who held positions of trust with access to the most sensitive national security information have made invaluable contributions to public debate and understanding. The publication of scores of such works without any demonstrated harm to the nation’s welfare belies the need for prior restraint of CIA officials.” That argument is unpersuasive if it is meant to suggest that allowing Snepp to waive the First Amendment would be wrong because it would work against the general welfare.

It is true that if the CIA and other security agencies are allowed to impose requirements of prior clearance of publication as a condition of employment, then the public will undoubtedly, over the years, lose some information it would otherwise gain. But the CIA’s arguments of policy against this point—that the efficiency of its intelligence gathering operations would be compromised if it did not have opportunity to review publications by ex-agents in advance—are not frivolous. No doubt the agency has exaggerated the importance of this review. It says, for example, that foreign agencies would stop giving intelligence to the United States if Snepp had won his case. These foreign agencies are not so stupid as to think that books by ex-agents are the principal sources of leaks from the CIA. Nevertheless, even if we discount the exaggeration, it is still plausible to suppose that the CIA will be more efficient if it has a chance to argue about this or that passage in advance, and alert its friends, including foreign intelligence agencies, about what will soon be in the bookstores.

But that means that there is a genuine cost-benefit issue of policy to decide: does the public welfare gain or lose more, in the long run, if books like Snepp’s are delayed and harassed? The question whether Snepp waived his rights is a fresh question of constitutional law. It is not settled by any earlier decision of the Supreme Court, or by any embedded constitutional policy favoring speech. If we assume that it is to be settled by some cost-benefit calculation about what will make the community better off as a whole in the long run, as the argument of Snepp’s lawyers may suggest, then the argument that it must be settled by the courts in favor of Snepp, rather than left to Congress and the people, is not very strong.

But the argument of his lawyers is much stronger, and seems to me right, if it means to call attention not to the general welfare but to the rights of those who want to listen to what Snepp wants to say. For these citizens believe that they will be in a better position to exercise their influence on political decisions affecting the CIA if they know more about the agency’s behavior, and their constitutional right to listen should not be cut off by Snepp’s private decision to waive his right to speak to them.

I must now say something about this constitutional right to listen. The constitution, as a whole, defines as well as commands the conditions under which citizens live in a just society, and it makes central to these conditions that each citizen be able to vote and participate in politics as the equal of any other. Free speech is essential to equal participation, but so is the right of each citizen that others, whose access to information may be superior to his, not be prevented from speaking to him. That is distinctly not a matter of policy: it is not a matter of protecting the majority will or of securing the general welfare over the long run. Just as the majority violates the right of the speaker when it censors him, even when the community would be better off were he censored, so it violates the right of every potential listener who believes that his own participation in politics would gain, either in effectiveness or in its meaning for him, were he to listen to that speaker.

The right to listen is generally parasitic upon the right to speak that forms the core of the First Amendment, and it is normally adequately protected by an uncompromising enforcement of that core right to speak. For the right to listen is not the right to learn what no one wants to tell.10 But the right to listen would be seriously compromised if all government agencies were free to make it a condition of employment that officials waive their rights later to reveal nonclassified information without checking with the agency first.

The law does allow private citizens or firms to extract promises of confidentiality, of course, about revealing commercial secrets or the contents of personal diaries or the like. But Snepp’s case is different. The right to listen is part of the right to participate in politics as an equal, and information about the conduct of the CIA in Vietnam is plainly more germane to political activity than information about business secrets or the personal affairs of private citizens. 11

So the issue of whether to enforce contractual waivers of the right to speak, given the constitutionally protected right of others to listen, is one that, like so many other legal issues, requires lines to be drawn. Two different lines were available to the Supreme Court in Snepp. It might have said that government agencies, as distinct from private persons or firms, may never make any waiver of First Amendment rights a condition of employment. That distinction would be justified on the ground that information about government agencies is presumptively information highly relevant to participation in politics, while information about private firms, while it may be, is not presumptively so.

Or the Court might have said that a government agency may never make such a waiver a condition of employment unless that condition is expressly imposed by Congress rather than by the agency itself. That weaker requirement would be justified on the ground that this decision—the decision whether the gravity of the threat to national security posed by former agents publishing material without prior review is sufficiently great to justify overriding the right to listen—is a decision that should be taken by the national legislature itself, rather than by an agency whose own interests in confidentiality might affect its judgment. It may well be doubted whether this second, weaker requirement is sufficient to meet the standards of the First Amendment. But it is not necessary to speculate further on that question here, because either the weaker or the stronger requirement would have argued for a decision in favor of Snepp.

It is worth asking, however, whether a different argument, not relying on the rights of others to listen, but instead relying directly on Snepp’s own First Amendment right to speak, would also have justified a decision refusing to enforce his contractual waiver. It might seem that such an argument, relying directly on Snepp’s own rights, must fail, because his choice to accept a job at the price of the waiver was a free and informed choice. If Snepp (who knew, as the lawyer for the CIA succinctly put it, that he was not joining the Boy Scouts) freely bargained away his full First Amendment rights by agreeing to a prior review, why should the courts now release him from his bargain when it proves inconvenient? Why should the courts now disable others from making the same bargain in the future, as they would by finding for Snepp now?

That was the CIA’s argument, and it prevailed. But it is not so strong as it looks, because it rests on a mistaken analogy between a constitutional right and a piece of property. The First Amendment does not deal out rights like trading stamps whose point is to increase the total wealth of each citizen. The Constitution as a whole states, as I said, the conditions under which citizens shall be deemed to form a community of equals. An individual citizen is no more able to redefine these conditions than the majority is. The Constitution does not permit him to sell himself into slavery or to bargain away his rights to choose his own religion. This is not because it is never in his interests to make such a bargain, but because it is intolerable that any citizen be a slave or have his conscience mortgaged.

The question that must be asked, when we consider whether any particular constitutional right may be waived, is this: will the waiver leave any person in a condition deemed a denial of equality by the Constitution? Since the First Amendment defines equal standing to include the right to report what one believes important to one’s fellow citizens, as well as the right to be faithful to conscience in matters of religion, the right of free speech should no more be freely available to trade than the right to religious belief. That is why the analogy to rights in property is such a poor one. If I make a financial bargain I later regret, I have lost money. But my standing as someone who participates in politics as an equal has not been impaired, at least according to the constitutional definition of what is essential to that standing. I have not sold myself into slavery or into a condition that the Constitution deems a part of slavery.

Once again, the argument does not justify the conclusion that a person should never have the power to agree not to publish certain information or to submit it for prior review. For not every such agreement leaves that person in a position that compromises his status as a political equal. The Supreme Court must therefore find a line to distinguish permissible from impermissible waivers of the constitutional right to speak, and either of the lines we defined when we considered, just now, the audience’s right to listen might be appropriate to protect the speaker’s right to speak.

The Court might say, that is, either that no waiver is permissible as a condition of employment in a government agency, or that no such waiver is permissible unless specifically authorized by Congress. But the Court, in its brief and unsatisfactory per curiam opinion, did not consider these possible distinctions, either of which would have supported Snepp’s claim. The Court assumed that anyone who is employed by a government agency might waive his First Amendment rights even without specific congressional authorization. That assumption makes the mistake of supposing that a constitutional right is simply a piece of personal property.

So Snepp should have been held not to have waived his First Amendment rights. That result is necessary to protect the rights of others to listen and also necessary to protect Snepp’s own independence. But this argument for Snepp depends on the conception of free speech and of the First Amendment that I defended earlier. It depends on supposing that free speech is a matter of principle, and therefore that it is a matter of great injustice, not simply an abstract threat to the community’s general well-being, when someone who wishes to speak his mind is muzzled or checked or delayed. Only if free speech is seen in that light does it become clear why it is so important to protect even an ex-CIA agent who signed a contract and knew he wasn’t joining the Boy Scouts. The Farber and Herbert cases show why the First Amendment so conceived will not give the press all the powers and privileges it wants. The Richmond Newspapers case shows why it might even take away some of what the press has gained. But the Progressive and Snepp cases show why that conception is nevertheless essential to American constitutional democracy. The First Amendment must be protected from its enemies, but it must be saved from its best friends as well.

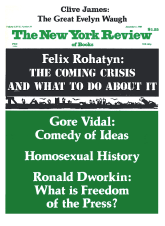

This Issue

December 4, 1980

-

1

The earlier case was Gannett v. DePasquale, decided only last year, which the press especially resented. That decision permitted a judge to exclude reporters from a pre-trial hearing, and Chief Justice Burger’s opinion in the Richmond Newspapers case states that the earlier decision was intended to apply only to such hearings and not to actual trials. But Burger’s own opinion in the Gannett case, as well as the opinions of other justices, seemed to cover actual trials as well, so that the Richmond Newspapers decision was probably a change of mind, as Mr. Justice Blackmun says it was in his own separate opinion in the latter case.

↩ -

2

Victor Marchetti and John D. Marks, The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence (Knopf, 1974).

↩ -

3

“The Rights of Myron Farber,” New York Review, October 26, 1978.

↩ -

4

Nor did the British House of Lords in a recent case in which British Steel Corporation sued Granada television to discover the name of an informer in the Steel Corporation’s management.

↩ -

5

Nat Hentoff, The First Freedom: The Tumultuous History of Free Speech in America (Delacorte, 1979).

↩ -

6

See Taking Rights Seriously (Harvard University Press, 1977).

↩ -

7

The Court faced that issue in the recent case of Houhins v. KGBX, in which prison administrators refused a television station all opportunities to investigate prison conditions. Perhaps because two justices were unable to participate in the case, the Court reached no effective disposition of the issues of legal principle.

↩ -

8

It is of course a different question, which I cannot consider now, how far Congress may constitutionally forbid citizens in general, and former agents in particular, from publishing information that may be genuinely secret and dangerous, like the names of present agents, as the bill I described earlier proposes to do.

↩ -

9

The CIA initially listed 339 sections of Marchetti’s book that it said disclosed classified information. These included a statement about Richard Helms’s briefing of the National Security Council, in which Marchetti reported that “his otherwise flawless performance was marred by his mispronunciation of Malagasy, formerly Madagascar, when referring to the young republic.” Marchetti and Knopf took the issue to litigation, during which the CIA itself conceded that 171 of these sections were not classified.

↩ -

10

As a legal matter, it is necessary to recognize an independent constitutional right in order to protect those who want to listen to someone who does not himself have a constitutional right to speak. The Supreme Court has held, for example, that the First Amendment protects Americans who want to receive political material from foreign authors who are not, of course, themselves protected by the United States Constitution.

↩ -

11

Of course in particular cases differences of this character may be differences in degree only. Commercial secrets, for example, may be matters of political importance. But if so, then the argument against enforcing waivers in such cases is correspondingly stronger.

↩