In September 1923 two young German Jews embarked together at Trieste on their way to settle in Palestine. One, Gerhard (Gershom) Scholem, born in 1897, was soon to become the greatest Jewish historian of our century. The other, Fritz (Shlomo Dov) Goitein, born in 1900, was perhaps slower in developing, from a conventional Arabist into a student of the Jewish-Arabic symbiosis of the Middle Ages and beyond. Yet the volumes of A Mediterranean Society, which Goitein started to publish in 1967, amount to a revolutionary picture founded upon new sources (mainly from the repository of documents of the old synagogue of Cairo) that bears comparison with Scholem’s achievements.

Such was the beginning of the second science of Judaism, no longer in Germany, where the first “Wissenschaft des Judentums” had developed a century before, but in the land of the Fathers—yet still through the agency of Jews born and educated in Germany. The new Wissenschaft, like the old one, is characterized by the exploration of recondite texts with all the resources of a rigorous philological method. It has, however, disclosed aspects of Judaism overlooked by the old Wissenschaft. Scholem has recovered the gnostic and cabalistic trends of thought and action never absent from Judaism since the Hellenistic age. Goitein has changed our knowledge of the intricate economic and social relations between Arabs and Jews.

The comparison between Scholem and Goitein could be continued at length, for both similarities and differences. Scholem came from an assimilated Berlin family where Hebrew had been forgotten: he started as a mathematician and acquired either on his own or with the help of traditional Jewish scholars the mastery of languages and techniques of analysis which was necessary for his success. Goitein, the scion of a rabbinical family, apparently learned Hebrew in his Bavarian home and Arabic at the University of Frankfurt. Scholem has not overlooked Islam (how could he, as the biographer of a Messiah converted to Islam?), nor has Goitein overlooked Christianity. But Scholem remains the historian of the European Jews living within the boundaries of Christendom, while Goitein’s special attention is reserved for the Yemenite Jews and for the contacts between Jews and Arabs through the ages, which gave the title to the most popular of his books (1955).

While we can only hope that Goitein will develop the short autobiographical sketch published as an introduction to A Bibliography of the Writings of Professor Sh. D. Goitein by R. Attal (Jerusalem, 1975), we can now actually read Professor Scholem’s autobiography for the years from 1897 to 1925. The original German text, Von Berlin nach Jerusalem, published by Suhrkamp in 1977, has now been translated into English by Harry Zohn.

There is no nostalgia or forgiveness in this book. Now, as fifty years ago, Scholem is determined to speak out. Now, as then, he is primarily concerned with the Jewish assimilated society with which he broke violently—and he broke, first of all, with his father, a Berlin printer. Secondly, he reiterates, at every step, that there was no place for a Jew, qua Jew, in German society and culture when he decided to leave, though Hitler was still for him nonexistent. Scholem remains Scholem, not a nationalist, not even a religious Jew, but a man who is certain that the beginning of truth for a Jew is to admit his Jewishness, to learn Hebrew, and to draw the consequences—whatever they may be (which is the problem).

Yet in this book he returns from Jerusalem to Berlin, to the parental house and to the maternal language, the tone of which, in its specific Berlin variety, is still unmistakable today in whichever language Scholem chooses to speak. Scholem is a great writer in German. Emigration has saved him from the distortions of German vocabulary and syntax which Hitlerian racism and the post-Hitlerian disorientation produced. The book is therefore untranslatable, in the precise sense in which Scholem declared Franz Rosenzweig’s Der Stern der Erlösung (“The Star of Redemption”) to be untranslatable until the day when the text will require interpretation for those who are able to read the original.1 It would be ungenerous to find fault with a translation which is competent and helpful, but was doomed to be insensitive. When Scholem says, “Die Tora wurde seit jeher in 53, in Schaltjahren 54 Abschnitte geteilt” (p. 128), he cannot mean: “The Torah has always been divided in fifty-three sections—fifty-four in leap years” (p. 98). Professor Scholem can be expected to know that according to academic opinion the division of the Torah into sections does not go back to Moses our Master.

The book ends with Scholem’s appointment to a lectureship in Jewish Mysticism at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem on the strength of the recommendation of Immanuel Löw, the author of a five-volume work on the Flora der Juden who had found in Scholem’s first book two excellent pages on the bisexuality of the palm tree in cabalistic literature. Scholem’s concluding remark is pure Wilhelm Busch: “So kam Lenchen auf das Land.” The translation substitutes, “Thus began my academic career.”

Advertisement

If there is no nostalgia, there are tenderness and gentleness in this book, and a remarkable avoidance of the most acute controversies and crises in which the author was involved. The book is full of friends rather than enemies. Ambivalent feelings are given a positive twist, as in the case of Franz Rosenzweig, who, if he had lived longer, would have been the only scholar capable of challenging Scholem’s interpretation of Judaism. Scholem’s brief account of his relations with Rosenzweig is a good sample of his writing in this book:

Every encounter with [Rosenzweig] furnished evidence that he was a man of genius (I regard the abolition of this category, which is popular today, as altogether foolish and the “reasons” adduced for it as valueless) and also that he had equally marked dictatorial inclinations.

Our decisions took us in entirely different directions. He sought to reform (or perhaps I should say revolutionize) German Jewry from within. I, on the other hand, no longer had any hopes for the amalgam known as “Deutschjudentum,” i.e., a Jewish community that considered itself German, and expected a renewal of Jewry only from its rebirth in Eretz Yisrael. Certainly we found each other of interest. Never before or since have I seen such an intense Jewish orientation as that displayed by this man, who was midway in age between Buber and me. What I did not know was that he regarded me as a nihilist. My second visit, which involved a long conversation one night about the very German Jewishness that I rejected, was the occasion for a complete break between us. I would never have broached this delicate topic, which stirred such emotions in us both, if I had known that Rosenzweig was then already in the first stages of his fatal disease, a lateral sclerosis. He had had an attack which had not yet been definitely diagnosed, but I was told that he was on the mend, and the only thing left was a certain difficulty in speaking. Thus I had one of the stormiest and most irreparable arguments of my youth.

Scholem’s father and Martin Buber (whose interpretation of Hassidism it was one of the life tasks of Scholem to repudiate) are not spared, but he has no harsh words for them. The book deliberately avoids entering into the details of the story of how Scholem freed himself from military service during World War I. Readers can turn to his interview with Muki Tsur, published some years ago, where he describes how, to avoid military service, “I put on an act without knowing what I was acting.”2

Scholem also avoids any deeper probing into his relations with Walter Benjamin and his wife Dora. The fact that Scholem had previously written a book and many papers on his friendship with Benjamin would not have made it superfluous to say something more definite in his autobiographical account, if the tone of the book in general had allowed it.

The book as it is can give us some first impressions about the wealth of emotional and intellectual stimuli Scholem collected in Germany before going to Jerusalem for good. It is not, however, an account of his intellectual formation, and therefore it cannot help to define the presuppositions of his work which were to remain constant throughout the next sixty years or so.

There is no question that Scholem left Germany at the age of twenty-six as a mature man with a program, a method, and a system of references which remained fundamental to his future activity. He may not have known that himself when he left Germany. He says that he then intended to devote only a few years to the study of Jewish mysticism; he expected to earn his living by teaching mathematics. But it turned out that the method for the study of Jewish mysticism he had expounded in his first articles on the subject in Buber’s journal Der Jude in 1920 and 19213 and his dissertation of 1923 (a critical edition of the mysterious gnostic text Bahir)4 would guide all his life work. More precisely, his concern with language in relation to mysticism, with analytical commentary in relation to sacred texts, and with anomia, or lawlessness, in relation to Torah, developed, in foreseeable directions, from these early studies.

Scholem tells us that he abandoned an earlier project of a dissertation on the linguistic theories of the cabala because he realized that he had first to bring cabalistic writings under philological control through critical texts and commentaries. What he did not do as a research student, however, he accomplished fifty years later in his essay on the name of God and the linguistic theory of the cabala (it is included in Judaica III, 1975).

Advertisement

Scholem’s book concludes with his appointment to a job in Jerusalem in 1925. He thus says nothing about the explorations he made in European libraries, especially during his momentous travels of 1927 (which was also the last time in which he had weeks of direct conversation with Benjamin: in 1938 it was only a question of days). In 1927 Benjamin was the first to be told about his discoveries in the manuscripts of the British Museum and of the Bodleian at Oxford about the antinomian trends of the theology of Sabbatai Zevi’s followers. But he did all this with the tools of interpretation he had brought with him from Germany. Nothing indicates more clearly the continuity of his method and the gradual clarification of the issues than a comparison between his prodigiously precocious article on the cabala in the German Encyclopaedia Judaica Vol. X, written in 1931, and the article on the same subject about forty years later for the new Encyclopaedia Judaica, written in English and published in Jerusalem.

I doubt whether there is anyone now writing who can analyze Scholem’s debt to German thought except Scholem himself. David Biale’s recent Gershom Scholem, Kabbalah and Counter-History,5 meritorious as it is in other respects, only confirms how remote most American Jews now are from nineteenth-century trends of German thought. For someone like myself who in the late Twenties and early Thirties read German books and talked to German friends in Italy, it is less difficult to overhear in the prose of Scholem and Benjamin the echoes of those German Romantics—Hamann, Humboldt, and von Baader—who were coming back into fashion. We often heard the dictum “Religion is a vowel and History a consonant,” which I later discovered to be a silly remark made in a letter by Rahel Varnhagen.

Not by chance, Rahel Varnhagen early caught the attention of Hannah Arendt for her mixture of Jewish guilt feelings and German metaphysical “Sehnsucht.” Another Jewess, Eva Fiesel (neé Lehmann), the extraordinarly able Etruscan scholar, summarized such Romantic tendencies in her book Die Sprachphilosophie der deutschen Romantik in 1927. Esotericism was in the air. Followers of Stefan George were multiplying among the younger generation of German Jews.

I was mildly amused when, in his by now famous review of the book by L. W. Schwartz on Wolfson of Harvard in the TLS of November 23, 1979, Scholem seemed to be surprised that Wolfson should boast to him of having delivered a little sermon for Harvard Chapel in which it was impossible to discover what, if any, religious belief he held. Was this so unprecedented in the circles in which Scholem moved in his youth? In his later American days, Leo Strauss, another great German Jew of the same generation, interpreted esoteric attitudes and double meanings as integral to the art of writing in an age of persecution. That persecution has something to do with esotericism is obvious; but the case of Leo Strauss himself—an addict of esotericism, if ever there was one, as those who have read the introduction to the English translation of his book on Spinoza (1965) must know—shows that persecution is not the whole of the matter.

Reticence, allusiveness, and ambiguity were characteristic of Walter Benjamin. Scholem for his part has excluded, even hunted down, any ambiguity or esotericism in the practice of scholarship, politics, or daily life. But he has fully endorsed esotericism as central to the ultimate objects of his life work. In “Towards an Understanding of the Messianic Idea” (1959), he wrote: “It is one of those enigmas of Jewish religious history that have not been solved by any of the many attempts at exploration just what the real reason is for this metamorphosis which makes knowledge of the Messianic End, where it oversteps the prophetic framework of the biblical texts, into an exoteric form of knowledge.” Even more uncompromisingly he wrote, in the “Ten Unhistorical Statements about Kabbalah” (never translated into English?): “The true language cannot be spoken.”

Such comments, however, do no more than suggest that “spirit of the age” which an older reader can recognize in Scholem’s writings. We are perhaps nearer to a real problem in the following observation. Scholem has always been an open, though respectful, opponent of the established German-Jewish science of Judaism, the influence of which went well beyond German Jews, as is evident in the work of Italian Jewish scholars from S.D. Luzzatto to Umberto Cassuto—the Biblical scholar for a while a colleague of Scholem’s in Jerusalem. What Scholem found wrong with this scientific approach is that it used categories of German Romantic thought without realizing that their creators (Herder, Humboldt, Savigny, etc.) were laying the foundation of a German nationalism that was incompatible with any autonomous Jewish culture inside the German nation.

He also reproached the Jewish scholars of the previous generations for being apologists, that is for expounding only those sides of Jewish life which the non-Jews were expected to like. Not only cabala and Hassidism, but also the less decorous aspects of ghetto life were kept out of sight. Not unnaturally Scholem has reserved his more negative judgments for the more recent offshoots of the old science: “Anyone who wants to become melancholy about the science of Judaism need only read the last twenty volumes of the Jewish Quarterly Review” (1959).

But one wonders whether Scholem’s reaction against that science is not itself rooted in other aspects of German Romantic thought that emphasized the magical and mystical potentialities of language and myth and indulged in negative dialectics. Nor were the German Romantics unaware of the rough and sordid sides of life. The hypothesis that both the old science of Judaism and the new science of Jewish Mysticism, which is identified with the very name of Scholem, reflect contrasting trends of German Romantic thought—one decisively Protestant, the other nearer to Catholicism—may help to establish the point in Scholem’s development where he turned his back on German thought and began to speak on behalf of a new Judaism.

Scholem has said more than once that if he had believed in metempsychosis he would have considered himself a reincarnation of Johannes Reuchlin, the Christian German humanist who in 1517 published De arte cabalistica, the main source of which Scholem himself discovered in the library of the Jewish Theological Seminary of New York in 1938. He has also constantly pointed out that his only predecessor in the study of the cabala to have lived in nineteenth-century Germany was the Catholic Franz Joseph Molitor. These are not casual remarks.

Yet there is indeed a point beyond which Scholem becomes unclassifiable according to any school or any category of German thought. That point is where his Zionist and his cabalistic pursuits intersect. For Scholem the primary meaning of Zionism, so far as intellectual life is concerned, is to make it possible for the Jews to recover all their past history and consequently to call into question all the aspects of their heritage. It is this freedom of movement into the past of the Jewish people that characterizes for Scholem the movement into the future called Zionism.

This radical and total reckoning with the past is obviously far more dramatic and painful in relation to recent times than to the Middle Ages. Scholem becomes correspondingly more drawn to value judgments when he turns his attention from the origins of the cabala to Sabbatai Zevi, the Polish-Jewish adventurer Jacob Frank, and Hassidism, not to speak of his comments about the “German-Jewish dialogue which never took place.” A book like Ursprung und Anfänge der Kabbala (1962) basically belongs to the history of ideas. Other books by contemporary German scholars—say Aloys Dempf’s Sacrum Imperium (1927) or H. Grundmann’s Religiöse Bewegungen im Mittelalter (1935)—can be compared with it in method, though not in depth of analysis. But all the researches leading to his great book on Sabbatai Zevi (published in English translation) are without any precedent in Germany.

There Scholem faces the entire destiny of modern Jews, and more particularly of himself. The sudden mad convergence of cabalistic speculations and Messianic hopes in Sabbatai Zevi and his prophet Nathan of Gaza attracted vast numbers of educated Jews who were longing for liberation and a new start within the Jewish tradition itself. In what is perhaps one of his greatest essays, “Redemption through Sin” (1937), Scholem went so far as to argue that the movement which led to the collective conversion of Frank’s followers to Catholicism in 1759 had its place within Judaism: “One can hardly deny that a great deal that is authentically Jewish was embodied in these paradoxical individuals, too, in their desire to start afresh and in their realization of the fact that negating the exile meant negating its religious and institutional forms as well as returning to the original fountainheads of the Jewish faith.”

There are pages of Scholem’s writing which give the impression that he recognized something of himself in the destructive and anomic personalities of Sabbatai Zevi and Jacob Frank and drew back from the abyss. As a collective phenomenon, Zionism has therefore become for Scholem the constructive answer to the purely negative conversions to Islam and to Catholicism of Zevi and Frank and many of their followers. Just because Zionism means to Scholem the opening of all the gates of the Jewish past, it is absurd to expect a specific religious message from him. Part of his case against Buber is that Buber misused scholarship in his religious message. The substantial correctness of Scholem’s exegesis of Buber is confirmed by Buber’s autobiographical fragments,6 which show that his discovery of the “I-Thou” religion is independent of his interpretation of the Hassidic tradition.

Nor can I see any evolution in Scholem’s thought. On the contrary, he seems to me remarkably constant in his intellectual attitudes, as he is in his political reactions to the daily problems of Israel. But it also seems to me that only as long as he tries to understand the cabala is he justified in considering himself a reincarnation of Reuchlin. When the cabalists turn into apostates or illuminists or, finally, Zionists—and then gather in the streets to march into a promised land—no model and no tradition can serve Scholem. He is left on his own, the first Jewish historian able to take full cognizance of the new situation. It is indeed possible that his precocious development prevented him in later years from grasping the full implications of what the Nazis have done to the Jews. Who, after all, is sure even now of what these implications are—or will be?

Other limits of his historical thought, easier to define, are suggested by the symbolic departure from Germany in the company of Shlomo Goitein. For it was Goitein, the more traditionally minded Jew, who penetrated the complexities of social relations between Jews and Arabs and entered into the mentality of the Jews of the Islamic world who, as Scholem is the first to acknowledge, were far from the center of Zionist attention. Even Fritz (Yitzhak) Baer, Scholem’s colleague and friend, who has given us so much original research and thought on many fields of Jewish history, never went beyond the Jews of Christian Spain during the Middle Ages.

On the other hand, it is difficult to appreciate adequately all the patience that Scholem, who is not famous for patience, has put into understanding his own relation to Christian thought, and especially to modern Germany. This is inseparable from his effort to understand his friend Walter Benjamin, who in his attempt to preserve his links with Germany and German culture finally chose Marxism or what he believed to be Marxism. It is no consolation to anyone to recognize that by carrying on his dialogue with Scholem to the end (and we have just now been given by Scholem their correspondence of the years 1933-1940) Walter Benjamin, that sad and noble victim of Nazism, contributed in ways he perhaps never suspected to securing for Israel and for the world one of the most remarkable historians of our century.

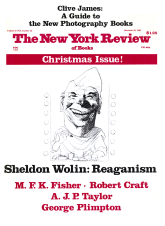

This Issue

December 18, 1980

-

1

See his letter in M. Buber, Briefwechsel II, pp. 367-368.

↩ -

2

In On Jews and Judaism in Crisis (Schocken, 1976).

↩ -

3

Der Jude 5, 1920, pp. 363-391; 6, 1921, pp. 55-69 (cf. his letter to Buber in the latter’s Briefweschel II, pp. 86-88).

↩ -

4

In its published form (Das Buch Bahir, Leipzig, 1923) the dissertation contains only the German translation of the text and a commentary.

↩ -

5

Harvard University Press, 1979.

↩ -

6

Begegnung, 1960, pp. 36-38.

↩