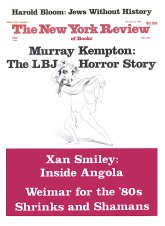

1.

Edmund Wilson observed that the works of Theodore Dreiser are like a newspaper full of “commonplace scandals and crimes and obituaries of millionaires, in which the reporter astonishes the readers by being rash enough to try to tell the truth.” Robert Caro is the most Dreiserian of our chroniclers. He proceeds in the same plodding, laborious, heroic way, which makes The Path to Power’s arrival at fashion something of an astonishment. For Dreiser seems fated always to be the least fashionable of great novelists, because he too much oppresses us with the weight of how capital is accrued and careers made.

Any catalogue of rascalities so enormous presents us, and perhaps even its compiler, with the danger that its scandals will be too great a distraction from its more consequential import as testament to the immutability of our social history. Caro’s Johnson, like Dreiser’s Frank Cowperwood, is a creature liberated from moral prejudices; and, unless we set aside our own, we will miss each one’s lesson.

Once we suspend ethical judgments of the personal sort, we begin to recognize that, in all affection and piety, Caro has thrown a dead cat into the garden of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s centennial. The Path to Power’s truly resonant message is that the richest rewards of social reform are reserved for the enterpriser with the wit and detachment to find his main chance in the spirit of his age.

In The Titan, Frank Cowperwood creates a barony of short-term Chicago street railway franchises and aspires to make it an empire with a $200 million stock issue. He is balked when the investment bankers refuse the uncertainties of a venture dependent upon the purchased kindness of Chicago aldermen, who could, at their corrupt will, peddle Cowperwood’s franchise to another tenant when his lease expires at the end of a bare seven years.

Cowperwood scents rescue from these perplexities when Joel Avery, one of his lawyers, reminds him that the New York State legislature has thought to temper the greed of the utilities by mandating a Public Service Commission, which will “fix the rate of compensation to be paid to the state or the city… [and] regulate transfers, stock issues, and all that sort of thing.” But such prospects are minor vexations when set next to the grander comforts for men of vision offered by a Public Service Commission’s power to extend the terms of franchises.

“I was thinking,” Avery says, “if at any time we find this business of renewing the franchises too uncertain here we might go into the state legislature and see what can be done about introducing a public service commission of that kind into this state.” Cowperwood at once detects the blessing that a lesser enterpriser would have mistaken for the curse of public regulation. Here was not the seed of destruction but “the germ of a solution—the possibility of extending his franchises for fifty or even a hundred years.”1 In the rope that the reformers had devised to tether him, Cowperwood had divined the knife that could cut his leash; and with that recognition, Dreiser brought populist dreams and progressive self-deceptions together to dust.

Caro has performed the same cruel office upon our delusions about the New Deal. His Lyndon Johnson climbs toward the heights on pitons driven for him by the Austin lawyer Alvin Wirtz and the building contractor Herman Brown, who had eyes as keen as Cowperwood’s for discerning the useful servant beneath the disguise of the apparent enemy.

Wirtz had left his seat in the Texas State Senate to become lobbyist for Humble Oil and Magnolia Petroleum, an infinitesimal shift in career directions, since he had been their steadfast retainer as a legislator. His scope widened when he attached himself to the expeditionary force sent to Texas by Samuel Insull, the Chicago utility magnifico, and demonstrated his value by bilking his former constitutents, the farmers, out of the acreage Insull coveted for a hydroelectric dam.

Then came Insull’s crash and the mid-construction halt of his Texas dam project. Its unfleshed bones remained the focus of Wirtz’s ambitions for power and patronage, and he managed to realize them by his quick understanding of the great change the Depression had brought, which was that government would henceforth be the prime, and in those days the only, capital resource.

With cool dispatch and no alteration of his retrograde social outlook, Wirtz transformed himself from Insull’s man in Texas to Roosevelt’s. What had been conceived as a private utility’s dam was reborn as the Lower Colorado River Authority and completed with funds from the United States Bureau of Reclamation and the Public Works Administration. Wirtz solemnized his new commitment to common cause with that stern foe of private rapacity, Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, by soaking the PWA for $85,000 in legal fees, an even larger score than he made in his simultaneous performance as receiver in bankruptcy for the Insull properties.

Advertisement

Wirtz’s first taste of government as universal provider was so savory that he went on to be Ickes’s undersecretary of the interior. The New Deal did not need to command his fervent belief to earn his approbation as a commercial instrument.

Herman Brown built the Marshall Ford Dam on the Lower Colorado outside Austin. His company, Brown and Root, had scrabbled up to a measure of affluence from the meager contracts at the disposal of Texas towns and counties; but his arrival at comparative comfort had in no way abated its founder’s possession by visions of statelier and more gainful monuments. The benevolence of an activist Washington made all those dreams realer than even he could have imagined; Brown and Root ascended from the Lower Colorado dam, to the rural electrification of Lyndon Johnson’s “Hill Country,” to the great naval station at Corpus Christi; and through every upward step, Herman Brown went on railing against the union, the blacks, and Franklin D. Roosevelt for coddling them even while he was Texas’s most sedulously coddled citizen.

But if Alvin Wirtz and Herman Brown could never love those who served them, they were men who paid the caterer. Wirtz had noticed Johnson when he was no more than congressional secretary to the hopelessly junior Rep. Richard Kleberg and had demonstrated a dexterity at wangling favors from the federal agencies remarkable for anyone in his low estate.

In the winter of 1937, Wirtz found himself pressed with an urgent need for the talents he had marked in Johnson. Until then, the Lower Colorado dam had been eating its way through the federal pork supplies thanks to the access afforded by Texas Congressman James Buchanan, chairman of the House Appropriations Committee. But then Buchanan was struck dead by a heart attack and all had horribly changed. Unless the dam could be salvaged by a new sponsor, Wirtz confronted the wreck of his ambitions and Brown the ruin of his fortunes.

Their only hope for salvation was to find a successor to Buchanan who could make up for the inescapable insufficiency of his stature if he were intimate enough with the federal warrens and determined enough about scouring them. Johnson was the only available candidate for his desperate job; and Wirtz gladly and even greedily hastened to support him. It was a dangerous speculation. Johnson was an unpromising challenger for a seat that several older and better-known stagers were tumbling to contest, in a district that included the poor Hill Country in which Johnson grew up. Wirtz found the means to remedy his chosen instrument’s defects by anointing him as the only administration loyalist in the race.

Shortly after his second inaugural, Roosevelt’s sense of proportion was overborne by the exuberance of an allbut-countrywide mandate and he introduced the Supreme Court reorganization bill that he hoped would cow the last lion in his path. Like Nixon at Watergate and Johnson at the Tonkin Gulf he had leaped at one of those chances to overreach that have so often tempted democratic politicians into converting the grandest electoral victories into triumphs for their enemies.

Every one of Johnson’s potential opponents was either opposed to or equivocal about the Roosevelt proposal; and Wirtz sensed at once that Johnson could only lift himself above the herd by seizing the president’s banner and turning this obscure by-election into a Texas referendum on the court plan.

L.E. Jones was Wirtz’s law clerk at the time and a witness to the strategy conference that sent Johnson on his road. “The discussion,” Jones said, “was that the court-packing plan might be a pretty lousy thing, but the hell with it, that’s the way to win. Wirtz said, ‘Now, Lyndon, of course it’s a bunch of bullshit, this plan; but if you flow with it, Roosevelt’s friends will support you.’ ” Johnson must, as Caro summarizes Wirtz’s teaching, base his campaign on “all-out, ‘one hundred percent,’ support for the President, for all the programs the President had instituted in the past—and for any program the President might decide to initiate in the future.”

Wirtz thereafter displayed his alacrity to adapt principle to convenience by composing speeches that pulsed with sentiments he disdained for delivery by a candidate who hardly half believed them. Thanks in part to Wirtz’s guile and to cash from oil companies, the contractors, and his father-in-law, but even more to his own demonic energies, Johnson was elected to Congress.

A few days later he traveled to Galveston for a visit with the president, who seized his hand with all the warmth earned by a success that was a rare balm in what was becoming a winter of affliction. Roosevelt’s gratification and the news photographs that celebrated it earned a welcome for Johnson from the New Deal’s beleaguered garrisons immeasurably beyond his actual station as the freshest of freshmen congressmen.

Advertisement

Once installed he did even less for the Roosevelt program on the House floor than the little he could have if he had tried, and threw himself instead into prodigies for the Wirtz-Brown Lower Colorado project. Caro has swept our minds of a cluster of misapprehensions about Johnson; and of these none has been more persistent and proved easier to clear away than the general assumption that he came to the legislature already a master of its processes. He might indeed have deserved that reputation early if he had not neglected an indisputable talent as a legislator for his true genius, which was that of the lobbyist.

He brought to that huntsman’s calling a nose without rival, whether he was raising it to sniff the air or abasing it to scrape the shoe polish of the guardians of the washrooms of power. He was a courtier with those unique powers of discrimination that find the readiest objects of their blandishments not among the few who breathe the heights but in the many who stand athwart and control the gates to points of vantage. Abe Fortas was only general counsel to the Public Works Administration, and, as secretary to the president’s eldest son, James Rowe could be called a White House assistant only by persons given to hyperbolic excess. They were nonetheless the most accessible rungs for a climber too keen-eyed to overlook a rung on the ladder that held a tenant who might help Wirtz and Brown. He even reached as high as Thomas Corcoran, Roosevelt’s personal favorite among his auxiliaries, who carried Johnson’s petitions to the president and had them granted with familiar offhand grace. (“Give the kid the dam.”)

Even this high favor wasn’t quite enough. The dam project still confronted formidable legal obstacles; and to clear them away Abe Fortas needed every bit of the cunning he would later expend as counselor to the privileged. But no sooner had Fortas opened the road than Work Relief Administrator Harry Hopkins discovered that to use $5 million of his appropriation for the Wirtz-Brown dam would violate at least three provisions of his operating statute, and rose up as the last and highest hurdle. Johnson responded by resorting to Rowe, who enlisted James Roosevelt, the highest authority within his grasp, and in due course Hopkins announced that he was withdrawing his opposition, because “we are doing this for Congressman Johnson.” All these proofs of his utility won Johnson the lifetime property of Brown and Root’s patronage.

Herman Brown’s distaste for the New Deal’s friendliness to the unfit was not easily mellowed by its many generosities to himself. At first he had so mistaken Johnson’s rhetoric for substance as to refuse to contribute to the congressional campaign whose results would so richly bless him. He could be drawn to Roosevelt’s standard only after Johnson pointed out to him, “It’s not coming out of your pocket. Any money that’s spent down here on New Deal projects, the East is paying for. We don’t pay taxes in Texas.” Once he had ingested the good sense of sacrificing one’s prejudices to one’s interests, Herman Brown cleaved fast to the New Deal and poured forth in its political service the bottomless purse that practical idealism has always valued more than the abounding heart.

The first call upon his resources came when that repellent old grouch John Nance Garner openly broke with the president and thought to snatch the succession for himself. The New Dealers reacted to this affront with a vindictiveness equal to the offender’s; and, even after they had beaten Garner in the rest of the country, they still thirsted to humiliate him by electing enough pro-Roosevelt delegate candidates in his own state to bring Garner to the 1940 Democratic National Convention so tattered that even Texas wouldn’t vote for him.

Caro makes it plain that Lyndon Johnson was this vendetta’s chief fugleman, although discretion inhibited him from bringing his larynx any closer to the stage than whisperings from the prompter’s box. The public captain of Texas’s anti-Garner formation was Alvin Wirtz and its paymaster was Herman Brown; and if a ray of social sympathy had ever happened into John Nance Garner’s crepuscular soul, it had been a flicker more than had ever intruded upon theirs.

One puzzle of Johnson’s progress is that he had so much more trouble convincing Herman Brown of his practicality than persuading Washington’s liberal cadre of his idealism. But then his performance as a congressman was as irrelevant to the New Deal’s housecarls as it was critical to Brown and Root. It did not matter to them if he was indifferent to his functions in a House of Representatives toward which they were themselves deeply hostile. To them a conscientious legislator was in the infrequent best case simple-minded and, in the numerous worse ones, pestilential.

The White House could count on him as spy and talebearer on his congressional colleagues—“He was a pack rat for information,” Abe Fortas told Caro—and his puny seniority excused him from blame for failure to advance its measures. On social occasions, he acted the voluble populist—“a perfect Roosevelt man,” as Edwin M. Watson, the president’s secretary, once uncomprehendingly described him. But in the Chamber itself he was so studiously silent that Caro’s toilsome diggings through the Congressional Record have unearthed only ten times when Lyndon Johnson addressed the House during his first eleven years there.

Still he maintained his aura as the perfect Roosevelt man wherever that odor was an asset, while he snaffled his tongue and now and then even withheld his vote when one of his great principal’s domestic causes was at issue. He was so judiciously allowing for the wind that, in 1948, when he was running for the Senate, the Dallas Chamber of Commerce was as delighted as General Watson would have been appalled to find that, on twenty-seven calls of the roll on Roosevelt proposals, Congressman Johnson had risen with the nays slightly more often than he had stood with the ayes.

It would appear to be the most taxing sort of work for anyone as superficially coarse as Johnson to anticipate the taste of the future and at the same time tailor himself to the modes of the present. The contradiction would have been harder to resolve if he had not had the luck to be one of the few visible embodiments of the Southern poor white in the period when he was the rage of liberal fashion.

Johnson shrewdly discerned the force of the imagination that had done the work of the eye and transmuted the poor white’s helpless stony reality into heroic metaphor, and he manifested himself in Georgetown as that metaphor’s incarnation. Mrs. James Rowe still remembers that “he could be very eloquent” when he talked about the Hill Country’s poverty and what the New Deal meant for it. His art as a seducer consisted wholly of isolating the piece of moonshine dearest to his object, then appropriating it and handing it back as though it were a gift. Naturally he confined his passions for the disinherited to the dinner table; in the cloakrooms he would be more vividly recalled for the coarseness of his ribaldry than for the tenderness of his social sensibilities.

Too many of Johnson’s equals in the House had already been enough put off by his pushy ways, and they would have been made uneasier still by any overly demonstrative expressions of populism; to have been elected is to become an incumbent and to be an incumbent is to view with more alarm than hope any effort to acquaint society’s victims with their grievances.

It didn’t take him long to understand that the proper route was not to the hearts but to the heads of his brother congressmen; and he found and took his path in the 1940 elections when the Democratic National Committee could only finance Roosevelt’s reelection effort by pinching the Democratic congressional candidates. Johnson may have brought as many as forty of his drowning colleagues to safety. Just in his first week as party fund raiser he produced an emergency levy of $30,000 from Herman Brown and at least $15,000 from the oil fields. The telegrams he sent with these life preservers regularly identified their source as “my good Democratic friends in Texas.” The contributions of these friends had, of course, been dispensed for Northern liberals they held in the lowest esteem; but they understood that expedience has claims more profound than conviction.

Their state’s authority in Washington resided in the House of Representatives where Sam Rayburn was speaker. Four Texans were committee chairmen and all the weight these faithful bearers carried depended upon maintenance of a Democratic majority. The New Deal’s congressional allies might abrade their nerves but they could not harm their interests. As insurgents on the floor, the House liberals had too few votes to work any approximation of their will; but as conscripts to the Democratic caucus, they had enough to assure control of the Congress’s machinery by their altogether more trustworthy elders and betters.

The 1940 election established Johnson as controller of a capacious electoral purse; and thereafter no reminder of his self-obsession and no degree of annoyance by the vulgarity of his manners could alter the respect bought for him by other men’s dollars. His mastery as legislative persuader had begun with this proof of his mastery as cashier.

2.

Caro’s Johnson is a monster who came to his world full-blown. When he was no older than twenty-two and freshly graduated from the Southwest State Teachers College at San Marcos, he was set in the devil’s mold:

[There] had been evident at San Marcos…the desire to dominate, the need to dominate, to bend others to his will…the overbearingness with subordinates that was as striking as the obsequiousness with superiors…the viciousness and cruelty, the joy in breaking backs and keeping them broken, the urge not just to defeat but to destroy…above all, the ambition, the all-encompassing personal ambition that made issues impediments and scruples superfluous. And present also was the fear—the loneliness, the terrors, the insecurities—that underlay, and made savage, the aggressiveness, the energy and the ambition. He himself saw this. On the day he returned to reminisce at his old college, he said: “The enduring lines of my life lead back to this campus.” The Lyndon Johnson of Capitol Hill was the Lyndon Johnson of College Hill; to a remarkable extent, nothing had changed him.

To define a fellow creature in such terms and to fortify the arraignment with so multitudinous a crowd of witnesses and so towering a mountain of documentation is to gibbet him on an eminence of infamy from which he will not easily be taken down. Caro said recently that he had approached Johnson inclined to revere and remained to loathe. Revulsion travels with no small cargo of risks; and one of them is that Caro will be at this work through two more volumes. We seldom envy the executioner in the tidiest of circumstances, let alone those in which he has contracted to flay the corpse for long after his whip has barely left a scrap of skin untorn.

Then too, revulsion is too excluding a sentiment; its object so swells as to push everything else from the stage; the repelled mind is too filled with the vices of a singular man to have room to absorb the faults that permeate his surroundings. But that disproportion is the price we have to pay for the unflagging adherence to James’s abjuration to dramatize that has enabled Caro to hold our interest throughout the seldom attractive and often squalid stretches of the first stage of his journey.

The dramatist’s engagement is with contrast, with the pitting of light against darkness, of hero against villain. Speaker of the House Rayburn is Caro’s chosen antithesis to Johnson; and as soon as we concede that he could hardly have found a more clear-cut one, we must give way to the surmise that if Johnson devoted his life to violating every civic ideal of our politics, he profaned a city already so pillaged that it scarcely showed a temple unrazed or a virgin unravaged.

Rayburn did manage to cling to much that was noble in his nature, although, to his advantage, it was never as large a proportion as there was of ignominy in Johnson’s. Caro in no way conceals Rayburn’s agility when it came to stooping when he had to. He was speaker of the Texas House of Representatives when he was only thirty and decided that it was time he went to Congress. Thereupon, “He appointed a committee to redraw the boundaries of congressional districts and the committee removed from the Fannin County district the home country of the State Senator who would have been his most formidable opponent.”

Caro has provided so much valuable instruction on minor sleights of Johnson’s statesmanship, like fixing elections among college students and among congressional secretaries, that it seems rather a loss that Rayburn and not Johnson was the author of this particular piece of craft. We might in that case have profited from a technical manual on the grander employment of rigging electoral districts.

Twenty-eight years afterward, in 1940, Rayburn was speaker of the House and commander of a Democratic majority in desperate crisis. At Johnson’s prompting, he traveled to Dallas to plead for financial assistance from its oil men and superbly brought off this coarse work without losing an iota’s assurance of his populist virtue. He could beg unashamedly from the Murchisons and the Richardsons because he had met them as scuffling wildcatters and had not noticed that they were by now barely distinguishable from those predators of great wealth he had growled at since he could walk.

Rayburn did not understand … how important he was to the wildcatters, how the protection he had extended to them in the past, and the protection they were hoping he would extend to them in the future, was one of the most significant factors in the accumulation of their wealth.

And thus, for the sake of Sid Richardson, huddled in “a rumpled suit” in “the same small bachelor quarters at the Fort Worth Club,” Sam Rayburn made sure that throughout his long sway over the House, no Democrat could expect assignment to its Ways and Means Committee until he had pledged not to disturb the oil-depletion allowance. We might more comfortably credit this stubbornness to the misapprehensions of a simple man if we could quite be persuaded about the kind of simplicity that contrives to obtain so many profits from being gulled. But ours is a politics where the unexamined hero is the only one we can keep. Somehow, whenever Caro holds Rayburn forth as contrast of best with worst, Lyndon Johnson seems less a freak of nature and more the extreme of a class.

Justice Holmes said once that Justice Harlan had a mind like one of the larger vises: it was incapable of holding small objects. Caro seems to have a mind of the opposite variety: it is a vise acutely calculated for the particular and not quite large enough for the general. We ought not to make Holmes’s mistake of construing an element of strength as weakness. We do not diminish the assembler when we think we see in his assemblage a pattern that has escaped him. It is proper, as it is sometimes unavoidable, to think ourselves wiser than Dreiser so long as we keep in mind that, had it not been for him, we should not be equipped to be wiser than he was.

What reservations abide with our admiration of Caro’s accomplishment have all to do with the sense that the lights in his composition are a touch too bright and its shadows a trifle too dark. Might not the problem be that the scene is too parched and dreary for the colorist? Caro on Johnson promises to stretch across a longer distance than Morley on Gladstone or Monypenny and Buckle on Disraeli; and in this instance the costume may be too big for the actor. That can be quite often the case with political men. Gladstone and Disraeli somehow involve us more when they are tourists than when they are statesmen; and if among all the fascinations of a Disraeli biography there so often intrudes the question of just what he did when he was prime minister, then how can we expect to be held in thrall by someone like Lyndon Johnson?

Johnson has hardly left behind a spoken utterance notable for any dimensions beyond those of vulgarity, and, except when he had to compose a campaign fund-raising letter, he was so indifferent to the written word that no sooner had he elected himself chief editorial writer of his college newspaper than he deputed his chores to his mother until he could dragoon a fellow student into taking on her ghostly task.

If Caro’s Johnson does not seem to offer us promises quite so large as were achieved in his Robert Moses,2 the blame does not lie in the portraitist but in the failure of his new ogre to seize the chances to wreak his untrammeled will that the old one gobbled like peanuts. Those opportunities are seldom available except upon one’s own ground; to attempt the global is to go up in smoke. Robert Moses was so prodigious a force for building and wrecking that we quite forget that he too wasted his energies on the paper that is the mere statesman’s only chance for a monument. When he was not yet thirty, he wrote the governmental reorganization plan that remains New York’s ruling charter, and that, given the torpor of politicians and the shoddiness of building materials, may outlive all his other works.

For all his own and his country’s cosmic pretensions, Johnson can never be Moses’s match, because he was wanting in the attentiveness to the surrounding environment that a great figure needs, whether for bettering or worsening it. He was a careless and unobservant man, and this is a loss because he had energies and concentrations that might have made him far more useful than most.

Just about all that is inarguably pathetic in Caro’s chronicle resides in the frequency of chapters that begin with Johnson plodding toward some genuine achievement and thinking himself in a backwater, and that end with him escaping at the first opportunity to undertake some more showy accomplishment, while rejoicing to have come back to the mainstream. He had no sooner displayed remarkable capacities as a teacher of Mexican-American children in Cotulla, Texas, than he deserted them to reenter his college where no more appetizing functions waited than to play prexy’s pet and classmate’s bully. Upon graduation he was hired to teach speech at a Houston high school, and seized the chance to fit its ragged debating team into a unit splendid enough to reach the finals of the state tournament; he was bending every fiber to make complete victory certain the next year when word came that a new and vastly rich Texas congressman needed a secretary; and he was off to Washington.

He returned to Texas as director of the state office of the National Youth Administration and performed so dazzlingly that his peers from the other provinces flocked to Austin for awed inspection. One day Johnson was escorting a Kansas visitor around his outpost when his eye fell upon the local newspaper’s account of the death of a Texas congressman. He put the poor pilgrim in his car and drove off with him to begin his campaign for the vacancy.

We can never know what such a man might have been, because every time he was at some branch of the Lord’s work, there would be the smell of the greasy pole, and he would be back at his horrid climb, eating the toads handed down from above and thrusting his toads upon those below.

Perhaps Caro is correct, and Johnson had been formed by the time he finished his adolescence and would never afterward be able to find any note between the sycophant and the overbearing. But even so, where could he have found and learned that note on the path he chose?

The elements of the final disaster that Caro adumbrates rise to the fullness of horrid presence in George Reedy’s memoir, which is in no way slighter than Caro’s for being so much smaller. When Johnson was majority leader of the Senate, Reedy was his special assistant and was carried with him to the White House as press secretary. Even this long afterward, his voice remains a convalescent’s, and his account is notable for a striking want of curiosity about Johnson’s life before they met; what he knows already must be enough of a torture to leave the sufferer disinclined to know more.

With Reedy we feel ourselves in the company of a spirit as lovely and serious as his master’s was ugly and trivial. There is no use blaming Johnson for having been unconscious of these qualities in someone much his better, for, as Reedy puts it with the forgiving authority of scars, which is no less formidable than the pitiless authority of Caro’s researches:

He had no sense of loyalty…and he enjoyed tormenting those who had done the most for him. He seemed to take a special delight in humiliating those who had cast in their lot with him. It may be that this was the result of a form of self-loathing in which he concluded that there had to be something wrong with anyone who would associate with him.

3.

Self-loathing may be the key, suggesting as it does that Caro could have no reader more capable of accepting all the justice of his flagellations than the no doubt still brooding and uneasy ghost of Lyndon Johnson.

Reedy grants full credit to Johnson’s sincerity in “trying to do something for the masses. His feelings for blacks, Chicanos, dirt farmers were not feigned. He felt their plight and suffered with them—as long as they did not get too close.” The final reservation allows the inference that this most intimate witness judges Johnson deficient in those domestic sensibilities without which the noblest sentiments wither. Whether closely watched by Reedy or exhaustively disinterred by Caro, he emerges as a nature unequipped for aspirations that could rise beyond, or achievements that were not hobbled by, a temperament compounded of the ostentatious, the volatile, and the vain.

Those monologues affirming his devotion to his roots could never have been so tedious if they had not been labors to conceal the canker of his heart. It is an insufficient excuse to note that he had endured his adolescence under the shadow of a loss of caste made more precipitate and painful for his father and mother by the pretensions that had preceded it. There remained a few men grateful to Sam Ealy Johnson, Jr., for his efforts as a legislator and a few girls who could still thank Rebekah Baines Johnson for many kind, if condescending, attentions; but not even memories this scantly redeeming availed their eldest son. Even the Richard Nixon of the grocery store seems a rather accommodating young man next to this monster child.

Caro can hardly offer us a reminiscence that is not appalling. We might tax him with prejudice if he didn’t give so much evidence of the historical conscience that would not leave out an affectionate tribute if one were forthcoming. But as it is, the painter and his audience are stuck with the unrelieved portrait of a son so indifferent to the manners, let alone the duties, prescribed by fealty that he could give encouragement to people who were already too contemptuous of his parents.

“What was the reason that he acted this way?” Caro asks. “That he screamed and sobbed over spankings that didn’t hurt, and cried hunger when he wasn’t hungry, and made public complaint about the sloppiness of his sisters’ bedroom?… Was it because, for this boy who had, from his earliest years,…needed public distinction—for this boy who was now a member of an undistinguished, poor family, and was himself awkward in athletics and only average in schoolwork—pity was now the only distinction possible?”

The appeal to pity continued to bob up whenever Johnson had no other device left to his hand. There is the unforgettable image that Doris Kearns has given us of his declining years in internal exile:

Terrified of lying alone in the dark, he came into my room to talk. Gradually, a curious ritual developed. I would awaken at five and get dressed. Half an hour later Johnson would knock on my door, dressed in his robe and pajamas. As I sat in a chair by the window, he climbed into the bed, pulling the sheets up to his neck, looking like a cold and frightened child.3

Doris Kearns taught at Harvard and was young and thus a symbol of two constituencies with which he had failed, as he had failed to succeed at anything when growing up in Johnson City. The world had turned out to be round, and once again, in the loss of majesty, he fell back on the claim to sympathy. Doris Kearns is to be commended and Johnson to be pitied that this terminal expression of the wounded self as total force could not quite engulf her shrewdness.

His origins were an unending discomfort because he was at once ashamed ofthem and oppressed by the manifold indications that they could never get over being ashamed of him. When he was Congressman Kleberg’s secretary and a more significant Washington presence than his employer, he arrived in Johnson City in the most impressive automobile at the King Ranch’s disposal. “He wore his flashiest clothes—and a manner to match,” Caro tells us. “‘Lyndon came back swaggering around showing what a big shot he was,’ says Clayton Stribling. ‘Same old Lyndon.”‘

His visits to childhood scenes would never thereafter be the returns of a native but the parades of a self-appointed and insecurely accepted ambassador from loftier precincts. We may indeed guess that this inability to fool his former neighbors contributed to the fierceness he brought to developing his skills at bemusing new acquaintances. His preference for lordly passages was a flight from injuries he risked whenever he essayed intimacy. He could not have brought so many airs home if he had ever managed to acquire graces. Even the fondness for blacks and Chicanos seems to have its source in this maimed diffidence toward his own class. They were subject peoples where he grew up, and he would be an old man before he had to give up assuming that they would not think themselves his equals, and thus would not be among his critics.

The few times where we find him beseeching the aid and affection of the humble descendants of ancestors like his own sound invariably like the forcings of necessity. He entered his first campaign for Congress naked except for Alvin Wirtz’s guile and his father-in-law’s cash, and he won it by plunging into Austin’s rural environs with a tirelessly sweating courtship of their farmers.

His first term was notable for producing his last undiluted contribution to bettering a portion of the human lot. The New Deal’s Rural Electrification Administration was new law but far from familiar fact of existence; and without Johnson’s alert address it might well have remained a vague and indefinitely deferred promise to the Hill Country, whose families still had kerosene lamps. He persuaded Roosevelt to relax the REA’s eligibility standards, organized the directing cooperative, and oversaw every managerial decision, including the construction award to Brown and Root, and thus, as not often before or since, satisfied his twin aspirations, beneficence to the needy and revenue to the deserving affluent.

Caro’s picture of Johnson as the bearer of light who did not neglect to be dispenser of contracts even in the noblest of his manifestations has proportions by no means smaller than those that emerge from his account of the epically monomaniacal Robert Moses at work upon Riverside Park. Still the richest contentment that Johnson drew from his monumental achievement seems to have been that it gave him a capital of gratitude that ensured the safety of his seat in the House so long as he wanted to stay, and thus relieved him from further debasement by fraternization with his constituents.

In 1941, when his grasp for the Senate returned him to electoral struggle, he incarnated himself as Roosevelt’s plenipotentiary to the provinces, in Caro’s image “a dominant, powerful figure…dogmatic, pontifical…demanding rather than soliciting support…. Far from establishing rapport with voters, he only managed to emphasize the feeling that he was not one of them.” He maintained this alienating posture until his assurance of victory turned to disquiet and in a bound he turned “as humble with the voters now that he feared he was losing as he had been arrogant when he had felt sure he was winning.”

He was already one of those whom only the extremest exigencies of survival can deflect from the compulsion to distance themselves from sources whose every drop of water is noxious to them. We can even suspect him of marking each stage of his ascent by the elevation it brought in the social credentials of his assistant, because, beyond all else, his was a nature that measured its fulfillments by the social status of those subject to its tyrannies.

As a congressional secretary and a state NYA director, he conscripted hisservitors from the high school debating team he coached and from among the more self-denying of his fellow alumni of Southwest State Teachers College at San Marcos, an institution whose curriculum was hardly more elevated than what prevailed at pretty much any Texas secondary school except his own.4 San Marcos’s students felt its dim refulgence in the academic cosmos as a continual wound; and his skill at salting it yielded Johnson at least one of the coups that established his sway over the petty domain of campus politics. He had set out to elect a majority of the seven co-eds annually selected as fairest flowers in San Marcos’s garden; and he attained this design by driving one maiden from his path with the threat that unless she abandoned her candidacy, he would expose her for having once, while among strangers, passed herself off as a University of Texas student.

There come moments in the contemplation of a nature fit for such trivial cruelties when the mind loses its patience. But this is to miss the point. Perhaps the best way to deal with Johnson is to dismiss his excesses as casually as the University of Texas did the comparative social crudity of San Marcos and as Harvard equally dismissed the University of Texas. True serenity of mind comes, of course, to those who can dismiss Harvard.

We only define Johnson’s agility when we notice how facilely he could exploit the resentments of the disdained. But we are close to understanding his pathos when we see how profoundly he agreed with the judgments of the disdainful. Naturally then, once congressional office gave him access to deeper reservoirs of talent, he stopped drawing from the San Marcos pool and hastened to the University of Texas for assistants like Walter Jenkins and John Connally.

At last he was a president for whom graduates of Yale and Harvard were grateful to work. The dreams of his childhood had run no farther than that; and the best we can say for him is that it was not enough. The self-distaste engraved in his childhood was inalterable. Raise the shit-kicker however high the godsmay, they doom him to travel to the grave kicking shit.

Even he must have found that out. The Johnson of the Senate and the White House who was so nobly borne by Reedy appears increasingly unfocused and exhausted next to the fiercely concentrated congressional secretary Caro has evoked for us. The change had set in as early as his last two years in the Senate. He had begun to drink and spend long, unexplained days in bed. The vice-presidency was more sodden still; but the presidency delusively revived him. It gave him the opportunity to do the best that was in him, which lay more in the direction of the mimetic than the creative. “He had,” Reedy observes, “an idea that he could become a great man by imitating great men.”

For two years he handsomely played Roosevelt and Kennedy; and then his electoral sweep brought the delusion that he was at last his own man and that the worst was forever behind him. He had reached his apotheosis and he described to Reedy his ultimate gratification at having arrived at every hope of glory: “I’ve been kissing asses all my life and I don’t have to kiss them anymore.”

Within three years, he would be begging for the sympathies of a Harvard teaching assistant. Some tragic hero, to come to twilight knowing so much less than was bred in the bones of any one of Colette’s women.

Reedy wishes that he had been a more reflective man. The degradations of the vice-presidency and the inanitions of the post-presidency were alike miseries to him, because, as Reedy says, “What could have been to a philosopher an era of growth was, in his eyes, a time of shame and failure.” But perhaps it is just as well that Lyndon Johnson was not a philosopher. If he had been, and one of the old Roman cast, he might have thought long enough to know that his life had not been ruined by loss of glory so much as by continual forfeiture of dignity. Then it is all too likely that he would have opened up his veins.

This Issue

February 17, 1983

-

1

Theodore Dreiser, The Titan, New American Library Signet edition, p.433.

↩ -

2

In The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York (Knopf, 1974).

↩ -

3

Lyndon Johnson and the American Dream (Harper and Row, 1976), p.17.

↩ -

4

As a prosecutor, Caro might have better persuaded us that San Marcos was a desert where the intellect was bleached to whitened bone if so much of his evidence had not been attested by one graduate who testified as a formerpresident of the American Political Science Association and by another who had gone forth to be professor of microbiology at Bryn Mawr.

↩