What is Beauty? The question has been debated on every level from the highest and most philosophical to the lowest and most pornographic, with opponents sometimes coming to blows over the rival charms of their ideal or real mistresses. Is She (for Beauty is traditionally female) a Platonic idea or a passing fancy? And, if corporeal, is she deliciously svelte, desirably stout, or divinely strong?

From the commercial point of view, we know, it is unimportant how Beauty is defined. What matters is, first, that the current definition with its hidden terms and imperatives should be universally accepted. (Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, who Have More Fun: if you are not a blonde, you will have less fun, and you will not be preferred by gentlemen; or—possibly worse—the men who prefer you will not be gentlemen.) Second, beauty should seem difficult to achieve and even harder to maintain. And finally, its pursuit should involve the greatest possible expenditure. For maximum profitability, fashion must be as artificial as possible, as tyrannical as possible, and as conventional as possible. Any falling-off from this standard reduces profits for someone. If I am perfectly content with medium-brown straight hair and comfortable old clothes, I am a danger not only to manufacturers of cosmetics and clothing but to newspapers, magazines, and television, all of which depend for their survival on advertising.

The most desirable mental state for a potential consumer, as Betty Friedan first pointed out, is a kind of free-floating anxiety and depression, combined with a nice collection of unrealistic goals and desires. To promote this frame of mind, advertisements announce that “you can be beautiful” and depict women of an inhuman, air-brushed perfection of face and figure on Caribbean beaches and in expensive restaurants and large shiny cars, being admired by large shiny men. The undeclared terms of the argument are: “If you were beautiful, you would live like this,” and “You are not beautiful now.”1

For anyone who is feeling depressed about his or her appearance, Lois Banner’s American Beauty is an excellent antidote. This detailed history of the changing standards of beauty from about 1830 to 1950 (with a glance at more recent developments) records the tremendous efforts that have gone into promoting the current style of looks over the years. It also—like Kenneth Clark’s The Nude (not mentioned, but obviously a precursor)—proves that almost all of us would have been considered devastating if we had had the luck to be born at the right time and place.2

Though American Beauty does not, as its jacket claims, cover two centuries “of the American idea, ideal, and image of the beautiful woman,” in most other ways it performs far more than it promises. Lois Banner’s approach to her subject, as befits the work of a serious social historian, is exhaustive. She is interested in fashions in personality, manners, and morals as well as in appearance. She has studied not only the history of dress and cosmetics and beauty contests, but the history of exercise and health reform, hairdressing, vaudeville, magazine illustration, the bicycle, boxing, May Day celebrations, and many other subjects. (Her notes, bibliography, and index alone take up seventy-five pages.)

As might be expected, this book is full of interesting data. One of its points is that the Victorian age was not what Lois Banner, in an appropriate if moribund metaphor, calls “a seamless whole.” In the 1850s, for instance, many fashionable ladies and working girls in New York wore heavy makeup and brilliant, flashy clothes; street-walkers, in order to distinguish and identify themselves, began to take up smoking cigarettes. By the mid-1870s, no virtuous woman used cosmetics, and smoking, perhaps as a result of its association with prostitution, did not become respectable for women until the present century.

The past, it often turns out, was more like the present than we think. In 1871, for example, the feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton criticized the young people of her time as (in Lois Banner’s words, presumably) “narcissistic” and “fixated on themselves”—in other words, a Me Generation. Like modern critics, Stanton blamed this on “the end of puritanical methods of childrearing and the substitution of child-centered, sentimentalized techniques.”

Lois Banner’s wide-ranging research allows her to make many serendipitous connections. She remarks, for instance, that Henry James’s Daisy (Daisy Miller), “a woman condemned for her sins against propriety” in the 1870s, had by the 1890s become the virtuous and cheerful Daisy of the Bicycle Built for Two, and her name a slang term of approval, as in “She’s a daisy.” Ms. Banner has even turned up a real-life Daisy Miller who in the same decade helped to found a “rainy day club” of working women who daringly shortened their skirts to three inches above the ground, attracting a shrieking and derisive crowd.

Advertisement

American Beauty is an admirable and necessary work. There has been nothing like it up to now; we have not even had a serious social history of American dress. Lois Banner’s exhaustive approach, however, has its disadvantages. Reading the book straight through is a chore: it is almost too dense with information, presented in flat, occasionally heavy prose. At times, large slices of data reappear in another context—suggesting that American Beauty is not designed to be read through, but intended as a reference source. I also caught one or two errors: Lorelei Lee, for instance, is not the heroine of Guys and Dolls; and consumptives, at least in the later stages of the disease, did not “become more beautiful” but grew pale and wasted, as in the famous Victorian painting Too Late by William Windus.

The theoretical aspect of the book, like the factual one, is exhaustive. Though Lois Banner declares that her approach is “historical, not sociological,” she appears to have read everything available on the sociology of modes and manners in America. She is familiar with so many explanations of, for instance, the rise of the hemline in the early twentieth century that it is almost dizzying. Perhaps because she is aware that most phenomena are multiply determined, she sometimes lists all the suggested causes of a change without weighting them. Were shorter skirts due to the influence of dress reformers, the growing popularity of sports, economic necessity, women’s increasing independence, or the vogue for health and exercise? Or, if all of the above, how were these factors related, and which were dominant?

At other times she approaches theory more critically. For example, after reporting Veblen’s belief “that fashion percolated downwards through the class structure” (can anything percolate downward?) she remarks, and later demonstrates, that the working class has also often been the source of new styles. This insight is not original, but the wealth of proof Lois Banner brings to it is exceptionally convincing.

One of the central lessons of American Beauty is that pressure on women to “improve” their appearance and conform to some current standard is nothing new. Over 130 years ago Godey’s Lady’s Book declared, “It is a woman’s business to be beautiful,” and it was assumed that every woman would spend as much as she could afford, or more, on clothes, and would engage in an unending beauty and fashion competition with her peers. Advertising of soaps and cosmetics was widespread by the mid-nineteenth century, and beauty contests date from even earlier. What makes the record of all this hullabaloo encouraging rather than depressing is Lois Banner’s demonstration that it was all so relative: the style of looks sought fervently in one decade might be completely out of fashion ten years later.

American Beauty distinguishes four types as characteristic of successive periods: “the frail, willowy woman” of the pre-Civil War years, whom it calls “the steel-engraving lady”; the “voluptuous woman” of approximately 1865 to 1890; the “tall, athletic, patrician Gibson girl of the 1890s,” and the “flapper” of the 1910s and 1920s. Changes in the female ideal have been noted before; what Lois Banner contributes is a nomenclature and impressive documentation. In general she refrains from conjecture about the deeper meanings of her four types of beauty. Instead she points out the obvious connections between fashion and social history, remarking for example that the youthfulness of the steel-engraving lady “underscored her purity and reflected both the nineteenth-century romanticization of childhood and its tendency to infantilize women”; while the voluptuous woman was “appropriate to an age exploring new models of sensuality.” Many other writers have made similar observations, and carried them further, seeing the history of female fashion and beauty during the period 1800-1930 as a gradual shift in the ideal from slim child to buxom matron and back. Banner’s “steel-engraving lady” and “flapper,” though their personalities were very different, shared the same adolescent appearance: the doll’s face and the slight figure.

What Lois Banner’s four—or possibly three—types most remind me of is a college course popular thirty years ago which included the “constitutional psychiatry” of William Sheldon, whose Varieties of Human Physique had recently appeared. After measuring a great many naked Harvard undergraduates Professor Sheldon had come to believe that there were three types of build: mesomorphic, in which muscle predominated; ectomorphic, mostly bone; and endomorphic, largely fat. Every body, according to his theory, could be classified as a combination of these types. We studied the scores of photographs in his book—alas, the faces and private parts of our male contemporaries had been blacked out—and, for mnemonic purposes, we designated mesomorphs as “horse,” ectomorphs as “bird,” and endomorphs as “muffin.” A look at the illustrations in American Beauty confirms that the steel-engraving lady and the flapper are mostly bird, the voluptuous woman mostly muffin, and the Gibson girl largely horse.

Advertisement

These three basic models appear to come back into favor at regular intervals. Today, in advertisements and on TV, beautiful women tend to be horse—tall, broad-shouldered, and dauntingly athletic. It is easy to be unconsciously influenced by contemporary standards, even when you are a skilled historian: Lois Banner, in a rare lapse from objectivity, speaks of “the athletic, natural look”—implying that the muffin and bird types of women are somehow unnatural. And though she declines to make any predictions, she finds it “difficult to imagine that the current emphasis on healthy bodies will decline, based as it is on solid medical knowledge.” I hope she is right—and I hope that some time in the future she will do for the years since 1930 what she has done so well for an earlier period.

To turn from American Beauty to Prudence Glynn’s Skin to Skin: Eroticism in Dress is to exchange serious scholarship for flair and expertise. Like her earlier book on twentieth-century dress, In Fashion, this work is witty, perceptive, and stylishly written. Whereas almost every paragraph in American Beauty ends with a footnote, Prudence Glynn’s insights are presented without reference to sources. Nevertheless she obviously knows a great deal about the history of costume. She also has the advantage of years of experience as fashion editor of the London Times and as an acute observer of British and Continental modes and manners, especially those of the aristocracy. (In private life she is Lady Windlesham, wife of the former Lord Privy Seal.)

Though her focus is on Europe, Prudence Glynn has some amusing things to say about American fashion as well. She is not always flattering:

Since Americans lack a long enough tradition in gracious living to back up their belief in their own taste, it comes as no surprise that the admired dress in America is the dress of overt power, which means of perfection, of outward materialistic success. [Nancy Reagan is] always impeccable and band-box fresh…a great turn-on in fashion, particularly to men who are struggling up the ladder (or are simply married to sluts).

As this excerpt suggests, Skin to Skin, like American Beauty, ranges well beyond its declared subject. Prudence Glynn comments on everything from the sartorial fixations of contemporary sports and rock stars to the persecution of fashion by the medieval Church:

No sooner had a primitive kind of couture evolved than the Church pounced…. Your new frock [has] a pretty train? Turn around, the Devil is sitting on it, you fifteenth-century Vogue reader you.

In the accompanying picture, from a contemporary manuscript, a small horned devil is in fact sitting on the lady’s train.

Prudence Glynn considers erotic appeal in men as well as in women. According to her, “The sexiness of any indication of influence and money should never be underestimated.” She also has a lot to say in favor of the appeal of an athletic physique and of dramatic, colorful costume: military uniform, sports clothes, and cowboy gear:

The dress of heroism comes in many guises [and] in many classes…. Working clothes suggest a mastery, either of all Gaul in the case of Roman armour, or of a vast animal in the case of the matador, [or of] a huge Mack truck covered in phallic horns and throbbing power from every cylinder….

American footballers and Spanish bullfighters [are both] dressed in the classic inverted phallic shape. Big, rounded shoulders, short neck and hair rather insignificant, tapering sharply to a tiny waist [and] skintight trousers highlighting small, high, rounded buttocks….

Whatever her subject, Prudence Glynn’s approach is lighthearted. The clothing preferences of transvestites and fetishists merely amuse her; and speaking of the semitransparent muslin dresses of the period just after the French Revolution, she remarks that the simplest way “for Society to get away with wearing practically anything, or practically nothing, was to pretend their fashions were inspired by some great by-gone age…. The most extraordinary displays of flesh have been permitted under the justification that they were ‘classically inspired.”‘ (Ms. Banner’s account of Victorian stage costume and the 1890s vogue for “living picture entertainments”—tableaux vivants—bears out this statement.)

Occasionally, Prudence Glynn’s opinions seem somewhat carelessly tossed off, or at least carelessly expressed. For instance, she claims that “the basic principle of dress…is vanity and eroticism.” This is of course a very suitable sentiment for a study of sex and costume; but it is at odds with her earlier claim, in In Fashion, that “the three fundamental reasons why clothing is worn” are “decency, warmth, and self-adornment.” To this criticism Prudence Glynn, with her customary insouciance, would probably reply with Walt Whitman: “Do I contradict myself? Very well then, I contradict myself.”

Most readers of Skin to Skin will not be troubled by such minor flaws; they will be enjoying themselves too much, even if they are only looking at the pictures. Like In Fashion, this book is lavishly illustrated with photographs, drawings, and cartoons—many of them extremely erotic, others extremely funny. It is larger than In Fashion, but not too large to read comfortably—a teatray rather than a coffee-table book—and is further enlivened by a great many wonderful color plates which—like the text—prove that ideas of sexual attractiveness are subjective and mutable. The underlying message is that erotic appeal is infinitely various: it does not depend on perfect proportions but on a skillful and daring presentation of the human resources we all share. And since the wish to be loved goes hand in hand with the wish to be admired, Skin to Skin, like American Beauty, is an excellent cure for the media-carried fear of mirrors.

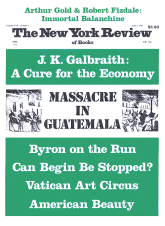

This Issue

June 2, 1983

-

1

Many slogans conceal such messages. For example: “You’re not getting older—you’re getting better.” Since the first clause is an obvious lie, we assume the same of the second; the hidden statement is “You’re getting older—you’re getting worse.”

↩ -

2

Lois Banner herself, to judge from the jacket photograph, would have been a beauty in 1890.

↩