The historian Adam Michnik was one of the most active members of KOR—the Workers’ Defense Committee—and during 1980 and 1981 was an adviser to Solidarity in Warsaw. Of his many important publications, the best known are The Church, The Left, A Dialogue, and Letters from Bialoleka. He was arrested on December 13, 1981, the night of the military coup in Poland, and interned in Bialoleka Camp near Warsaw. In the fall of 1982 he was charged, together with some other members of KOR, with attempting to overthrow the state. He now awaits trial in Investigation Prison in Warsaw, where this interview with a Polish visitor took place.

—Jeri Laber, Helsinki Watch

Q: You have now been locked up longer than Solidarity existed [legally]. What is your stratagem for doing time?

A: The idea is always the same: to work, and to believe that this is meaningful. I read a lot; I try to use my time to study. The news reaching us from outside suggests that doing time is meaningful, that it is a part of the Solidarity resistance movement, especially now, when the authorities make up successive lies concerning the progress of normalization and understanding [with society]. Our stay in prison is proof that normalization remains elusive.

Q: I understand that in this situation you want to avoid pathos even when you really live under the shadow of Zbigniew Herbert’s great words: “You have too little time / it’s necessary to bear witness / be brave when reason fails / be brave.”

A: Since the situation is pathetic—I don’t have to be; I am simply guided by an instinct for self-preservation. I have long known that one must never strike deals with the police. Such deals always end badly. They only know how to lie—but they are quite good at it. They are also stupid; unfortunately those they interrogate are sometimes even greater fools. So Herbert is right—the most important thing is courage and dignity. In general, Herbert is an excellent, perhaps even the best, writer for these times of contempt. This is not only my opinion, as more and more people refuse to talk with the gentlemen from the security police. It doesn’t require pathos, or great wisdom, only a little courage.

Q: What was your impression of the Holy Father’s visit? It was you, the political prisoners, whom the Pope addressed in his first speech on Polish soil.

A: Like everyone else in Poland, I greeted his visit with great joy and hope. One consequence of the Pope’s visit is that many of us were released. But in the long run there will also be other consequences.

One important event took place in prison: a majority of prisoners declared a hunger strike, demanding, among other things, that they be given the status of political prisoners. The strike was voluntary, no one was pressured. I, for example, did not fast. It was a moral gesture of great significance. I hope that this struggle for the status of political prisoners will be noticed by the Episcopate. Many prisoners do not understand the bishops’ silence on this matter. After all, this is not a question of politics but of defense of human dignity.

Q: The KOR trial is an astonishing phenomenon: The authorities wanted to unmask you, but they unmasked themselves. Almost no one confessed or gave depositions. For the umpteenth month you have been digging through the indictments…

A: The prosecutor even had an idea to prevent me from reading them, one of his most brilliant ideas. I will describe others during the trial. Well, it will be a monstrous trial. The authorities are not unmasking themselves now, they did it on December 13, 1981. They only reveal their own stupidity now. Mr. Jaruzelski had the great idea of adding a year of internment to our sentences. These gentlemen display unusual intellectual creativity when it comes to thinking about the ways of imprisoning people. The trial can’t possibly disgrace us, but it may disgrace them. We want it to take place. Our prosecution dossiers are a gold mine of information, not so much about KOR as about its present overseers. At the trial I will recount what I discovered in these files about the “gloomy conductors of prison trains,” as Milosz would describe them. Jaruzelski trusts the discipline of the judges who will be sentencing us, but he should not hope for the discipline of the accused.

Q: Nevertheless, you owe this psychological luxury to yourself, not to Jaruzelski or to [Minister of Internal Affairs, General Czeslaw] Kiszczak.

A: Above all I owe it to you, to Solidarity underground. You know that the Radio Solidarity broadcast to prisoners was magnificent. It was an injection of strength. I didn’t believe that a word from Solidarity could reach here. When it did, I understood how much had changed in Poland. Nobody feels alone anymore, and this is the government’s greatest defeat.

Advertisement

Q: Your Letters from Bialoleka prove that dialogue through the bars is possible. You were right when you wrote, in April 1982, that a “Long March” awaited us, rather than a “Sudden Change.” What future scenario would be worthwhile to think about?

A: I think that it isn’t worth thinking about coming to an understanding with the present ruling group. It’s a waste of time. This group may have sharp disagreements with the party “concrete” [i.e., the hard-liners], they may even be at each other’s throats, but on one issue they agree: in Poland, Solidarity’s place is only behind the prison bars. One should understand the struggle taking place within the apparatus of power, but one should not vest even the smallest hope in any of the disputing factions. Our only chance is to build a widespread, multifaceted front of civic action and determined resistance. I am not a prophet so I don’t know when and from where the impetus for change will come, but changes in the direction set by Solidarity are inevitable.

The importance of organized [underground] structures can’t be overestimated. They create a possibility that we won’t waste our next chance. Most likely it will be a “Long March.” Prospects for [our] movement must be measured in years. It should pay special attention to the situation in the Soviet Union. Upheavals are approaching there. Today, two virtues are most important, on both sides of the prison wall—consistency of purpose and patience.

Q: In your lectures at the “Flying University” you used to explain that Polish tragedy consisted in the fact that society had been condemned to sovietization, no matter what actions were taken. What sources of hope do you see today in Poland and in the world?

A: I have an optimistic nature. In order to begin, it is necessary to believe that things can be changed. If it were not for past optimists, like Cardinal [Stefan] Wyszynski, [Stefan] Kisielewski, and [Zbigniew] Herbert, all of whom resisted, we wouldn’t have today what we do have. In social terms, resistance always pays. Communism as a social system, and as ideology, exhausted its power. It is a conservative dictatorship of a narrow elite—the “nomenklatura.” The growth of resistance against totalitarian communist structure is international in scope and will intensify. We, and the whole so-called socialist camp, face either democratization or progressive decay and possible war. We work for democracy and peace. Jaruzelski, on the other hand, believes in the possibility of restoration of traditional communism by military means. We would be subjects, and he—a more or less benevolent monarch. However, that is utopia. He is a greater utopian than [Edward] Gierek. Genuine realists are now with Solidarity.

Q: You have always been an opponent of conspiracy. Did you change your mind?

A: The situation has changed. Leaders in hiding are necessary; they are a symbol of the entire national movement. I know how difficult their life is, and I honestly admire them. I know what dangers face them in the underground, and I wrote about that in one of the Bialoleka letters. But we have no choice. With the whole nation we were pushed underground. In fact everyone is conspiring. To stop the conspiracy on the government’s conditions means capitulation. I should remind you that after 1947, following the appeals to come out of hiding, with promises of amnesty, all leaders of the Home Army went straight to jail. Jaruzelski will not rest until his territorial operations groups break our moral spine. Thus we must defend ourselves.

Q: When amnesty was announced you were kept in prison as one of the regime’s hostages. How do you appraise the amnesty and the lifting of the state of war?

A: It looks like another comedy staged by the ruling group. I am glad of course that many people were freed. I am especially happy about the release of people who provided an example of how to behave during investigation and trial, like Zofia Romaszewska. But what kind of amnesty is it, if it leaves in prison [Wladyslaw] Frasyniuk and [Piotr] Bednarz, [Andrzej] Slowik and [Karol] Modzelewski, [Andrzej] Gwiazda and [Marian] Jurczyk?

The lifting of the state of war, in turn, can only be a ritual gesture for the benefit of foreigners, and those rather badly informed at that. Nothing changed for the better. Even artists, actors, and writers continue to pose a danger for the social order that Jaruzelski dreams about. The state of war was allegedly imposed to forestall civil war. Now it turns out that the war-mongers are artists, actors, and writers. We studied this topic in Stalin’s times so we know how it all ends. With terror.

Advertisement

Q: What do you think of Jaruzelski?

A: I rarely think of him. His program is to make the life of the whole society totalitarian at the smallest possible cost, but so far as the Russians are concerned, they are not satisfied with him anyway.

Q: Why?

A: Because they are insatiable. So long as farmers have not been chased into kolkhozes, and Catholic priests into catacombs, they will continue to dream the nightmare of counterrevolution. People in Moscow stand behind the “concrete.” And behind the attacks on the presently ruling group.

Q: Don’t you think, then, that Jaruzelski is a lesser evil?

A: I am farthest from such thinking. Jaruzelski defends the chair coveted by, let’s say [Foreign Minister Stefan] Olszowski. What have we to do with this? Concerning Solidarity, there is no difference between them. They differ with respect to technique. During an interrogation one investigator screamed at me, shook his fist, and threatened that I would end up rotting in jail if I didn’t talk. Then another one came in and said: “But Citizen Major, why do you get so upset? Mr. Adam is a man of high culture and intelligence. He will say everything without screaming.” The second man thought like Jaruzelski, the first one like Olszowski. But both were officers of the security police and their goal was the same.

Q: Are you afraid of deportation?

A: This has been suggested several times to Jacek Kuron, even recently, that he may emigrate any time he wants. I also received such suggestions. Our cases are probably not exceptional.

Perhaps Jaruzelski regards this as a humanitarian gesture—after all I could be shot for spying for, let’s say, the United States. Why not? Polish courts are the most liberal in the world—when it comes to evaluating the evidence. However, I am not interested in emigrating. It would be much better for Poland if it were Jaruzelski, Olszowski, and Kiszczak who left. I like living in this country. Even in prison. I prefer not to think about deportation; Polish criminal law does not allow such a possibility. I understand, however, that the government may entertain such ideas. So long as we stay in prison no rational person can believe that “order reigns in Warsaw.”

Q: We feel indebted to you. By leaving you in prison the communists showed whom they fear most, and to whom we owe that great breath of August. You can be sure that so long as you remain imprisoned, we shall always say “Non possumus,” like Cardinal Wyszynski in the years of Stalinist terror. After the amnesty, Poland has been transformed from a prison cell into a prison exercise yard. Either we go out of prison free or they can lock us up together with you, but we shall not allow ourselves to be led into an exercise yard. We remember that August exploded because of one wronged person, in defense of that one person, Anna Walentynowicz….

A: Thank you for your words, and for making it possible for me to speak. We shall try not to disappoint those who put trust in us—our friends on the other side of the prison bars. In fact you are risking much more over there than we do here.

—translated by Jerzy B. Warman

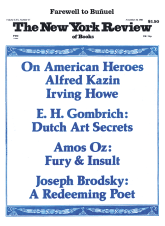

This Issue

November 10, 1983