Few colonizers have attached to the romance of the country they have conquered as the Anglo-Irish have. It may be that no other colonizers have been quite so literary; it may be that the racial closeness of conqueror and conquered has called forth a marriage like that of intense, doomed cousins: irresistible to the romantic imagination, damaging for generations. In creating a myth for themselves and for the Celtic Irish, the Anglo-Irish have seen themselves as victims frozen in a frame of grand heroic isolation. In their great houses, with their famous horses and heraldic dogs, they saw themselves suffering: misunderstanding, loneliness. They brooded over the half-beloved natives who could not, in any way that could be trusted, love them back. Blood, poetry, and magic—the coin of the Irish Irish drew them in and yet repelled them. Still they were, deep in their hearts, not English. They belonged nowhere except, passionately, where they were.

As the economics of Ireland turns the great estates into hotels, the old romance cannot survive. Yet it may be impossible to write about Ireland without romance of some sort. The strength of the impulse would seem to be borne out by William Trevor, that highly realistic chronicler of the slow rot of English life, whose reports of England abound in painful details of the corruption and lives shaped by reruns of Kojak and Benny Hill, by Wimpy Bars and office affairs and the artifacts of local sex shops.

He has invented his own romance about Ireland, a different one, to be sure, from the one that pervades the literary imagination: it is not lit by the Celtic twilight. Trevor, although Irish Protestant, is middle class, the son of a bank manager. He focuses on the ordinary Irish, caught up in the necessities of Irish history. Trevor is fascinated, in his stories about Ireland, by a pervasive evil that must intrude upon the innocent. His romance, which is a moral one, suggests that the Irish, or some of them—the victims—combine viciousness and innocence in ways inaccessible to the English.

For the Irish, the present constantly butts up against the past in the form of a political reality that is at once utterly present and archaic. Attempts at ordinary decency collide with a tradition of brutality and hatred; myth, despite the will of the living mortal, or beckoned by him, eventually must intrude.

In his story “The Distant Past,” an elderly, eccentric Anglo-Irish brother and sister have made peace with their neighbors in the southern Irish town they’ve lived in all their lives. The “trouble” in the Twenties—when the butcher held a gun on them, and the shopkeepers imprisoned them in their great house—has been forgotten, has become, for them all, a town joke. But when, in the Seventies, another time of the “trouble,” their town is ruined economically by the resulting decline in the tourist trade, its citizens turn ugly. Friendships of fifty years erode and the two old people know that the best they can look forward to is a lonely, isolated death. The story which begins with the hopeful “In the town and beyond it they were regarded as harmlessly peculiar” ends: “It was worse than being murdered in their beds.”

In “Beyond the Pale,” an unhappy English tourist meets a young man revisiting the place—now a fancy hotel—where he used to meet his childhood sweetheart. The girl has grown up to become a terrorist, and the young man, appalled by the deaths she has caused, kills her, then returns to the place of their childhood happiness to kill himself. Yet, in another time, in another place—in England, perhaps—the two might have married, brought children of their own back to the hotel. Distraught, the English tourist asks what causes this perverse necessity: “Has it to do with the streets they came from?” she asks, “Or the history they learnt, he from his Christian Brothers, she from her nuns? History is unfinished in this island; long since it has come to a stop in Surrey.”

“The Troubles”—the term itself has a mixture of domesticity and drama—is an irresistible subject for the Irish writer: the relation of past to present, the sickening sense of historical repetition, the unsure conjunction between individual will and national fate—its very attractiveness contains its literary dangers. The mistake that is usually made—as in, for example, Thomas Flanagan’s sprawling The Year of the French or Julia O’Faolain’s admirable but convoluted No Country for Old Men—is for the author to be too inclusive, to trace pattern with too heavy a hand, to fall himself for the romance of violence. These dangers Trevor has avoided both in his stories and now in his new novel by his spare, elliptical treatment of political and family history. The temptation for the writer about Ireland is to go epical; Trevor’s novel instead has a condensed lyrical tone.

Advertisement

It is a daring technical move because his plot is full of complications and action. Massacre, suicide, madness, revenge, illegitimate birth are all contained in a narrative of 240 pages, a narrative written largely in the form of conversations between a husband and wife who have been forcibly separated for fifty years. The novel’s action begins in 1918, when Willie Quinton is a boy, although the past is felt always as a living presence: we no sooner learn about the situation of the current Quintons than we hear about their nineteenth-century ancestor Anna.

She is the first of a series of three English brides who make the journey from Dorset in the course of a hundred years, cutting themselves off from the decent life of the English provincial rectory for the romantic soil of Ireland. With Anna Quinton, who dies of famine fever contracted when she tries to help her miserable neighbors, the family tradition of active concern for the Irish Irish is begun.

Nineteen-eighteen is a time of peace and prosperity in Ireland for the Quintons. Kilneagh, the Quinton estate, is presided over by Anna Quinton’s grandson, Willie’s father. The household has a reputation for taking in strays; in one wing of the house live Aunt Pansy and Aunt Fitzeustace—middle-aged maiden ladies—Philomena, their maid, employed out of charity when the priest she worked for died, and Father Kilgarriff, Willie’s tutor, a Roman Catholic priest unjustly defrocked for his kindness to a young girl.

“I wish that somehow you might have shared my childhood,” writes Willie to his wife, sixty years later. For up to 1918, Willie’s childhood is that rare thing: happy, and Trevor succeeds in that even rarer thing, portraying a happy childhood convincingly. The details of Willie’s life are rendered lightly, offhandedly: ” ‘Agricola,’ Father Kilgarriff said on the day I began to learn Latin. ‘Now there’s a word for you.”‘ The Quintons live a good and happy life; we read of it with a pleasure that allows for no apprehension of what is to come.

The tragedy begins with the burning of Kilneagh house by the Black and Tans, led by a Sergeant Rudkin, who is seeking revenge because an employee of the Quinton Mill has been hung on the estate by Irish revolutionaries. The murdered man was hired by the decent Quintons, who couldn’t refuse employment to a returning soldier. Kilneagh is turned into a ruin; Willie’s father and two sisters are killed, and Willie’s mother becomes a reclusive alcoholic. She leaves Kilneagh for lodgings in the town of Fermoy, where she is nursed by a devoted Kilneagh servant while Willie miserably attends the town school.

Trevor’s rendering of the slippage of this elegant, passionate woman is wonderfully done. Occasionally, for her son’s sake, she rallies: for a visit to the lawyer, tea at the local hotel, but the attempts are disastrous, and an embarrassment to Willie. She retreats to her bed where she cryptically admonishes him to avenge his family’s history upon Sergeant Rudkin, who is now a greengrocer in Liverpool.

Despite all the horrors he has witnessed, Willie seems to possess the potential for a normal future. Trevor’s account of his days in his boarding schools is a skillful comic interlude that, like the accounts of Willie’s childhood, make the shock of what follows far more intense. His mother kills herself on the one day in years that her servant has gone home to visit her family. At her funeral, he sees again his cousin Marianne, who becomes the last Englishwoman to be pulled into the Irish fate. In a combination of sympathy and frustration, she offers herself to Willie, and conceives a child. She runs away from finishing school in Switzerland, writing her parents in Dorset only the short heartless message “Willie will take care of me,” and returns to Kilneagh to find Willie gone, and the rest of the household and town mysteriously silent about his whereabouts. Marianne’s desperate search for him, her confusion, her adolescent sense of being the only uninitiate in a world where all the adults know the code, are excruciating. Only gradually does she learn that Willie has murdered Sergeant Rudkin in Liverpool, and must spend the rest of his life a fugitive to escape punishment.

Marianne returns with her child, Imelda, to Kilneagh. The fate intended for both of them seems at first benign: the old aunts take them in; Father Kilgarriff presides over the house. But of course, the Quintons are “fools of fortune”; ordinary life will always escape them. “There’s not much left in anyone’s life after murder has been committed,” Father Kilgarriff tells Marianne. But Marianne refuses to see Willie’s act as murder: for her, it is an affair of honor, and of ancient justice. She writes in her diary:

Advertisement

I had never even heard of the Battle of the Yellow Ford until Father Kilgarriff told me. And now he wishes he hadn’t. The furious Elizabeth cleverly transformed the defeat of Sir Henry Bagenal into victory, ensuring that her Irish battlefield might continue for as long as it was profitable: Father Kilgarriff had told you too, in the scarlet drawing-room with the school-books laid out between you. Just another Irish story it had seemed to you and perhaps, if ever you think of it, it still does. But the battlefield continuing is part of the pattern I see everywhere around me, as your exile is also. How could we in the end have pretended? How could we have rebuilt Kilneagh and watched our children playing among the shadows of destruction? The battlefield has never quietened.

Marianne, as well as everyone the child Imelda meets, insists on turning Willie into a hero. “Often Imelda tried to imagine him, wondering if he was like the Earls of Tyrone and Tyrconnell. The nuns at the convent spoke of him as a hero, even as somebody from a legend, Finn MacCool or the warrior Cuchulainn.”

But when Imelda reads the details of how her father murdered Sergeant Rudkin, she finds it neither beautiful nor heroic. The newspaper account allows for no glamorization: “The head was partially hacked from the neck, the body stabbed in seventeen places.” Finding it impossible to reconcile the bloody reality of her father’s act with the myth created for it, Imelda becomes insane.

After fifty years of wandering, Willie returns home to Kilneagh, to his mad, middle-aged daughter, and his seventy-year-old bride, never fully known. Willie and Marianne begin a peculiar old age in which they can live peacefully with their history of horror. Together they return to their land, and they watch their daughter. “They are aware that there is a miracle in this end… They are grateful for what they have been allowed, and for the mercy of their daughter’s quiet world, in which there is no ugliness.” Imelda seems, although destroyed, a vessel of beauty and health for others.

Imelda is gifted, so the local people say, and bring the afflicted to her. A woman has been rid of dementia, a man cured of a cataract. Her happiness is like a shroud miraculously about her, its source mysterious except to her. No one but Imelda knows that in the scarlet drawing-room wood blazes in the fireplace while the man of the brass log-box reaches behind him for the hand of the serving girl. Within globes like onions, lights dimly gleam, and carved on the marble of the mantelpiece the clustered leaves are as delicate as the flicker of the flames. No one knows that she is happiest of all when she stands in the centre of the Chinese carpet, able to see in the same moment the garden and the furniture of the room, and to sense that yet another evening is full of the linnet’s wings.

In inventing Imelda’s fate Trevor himself seems to have succumbed to the pull of Irish myth. She embodies the Irish genius: visionary, magical, poetic. The Irish have no talent for action; the triumphs of the active life elude them. When they try to act, they are doomed usually to tragic failures easily avoidable by any other race.

At the end of the novel, the Quintons are at peace, not only with old age but even with insanity. It sounds, almost, like the stuff of melodrama, brimming with high sentiment. Yet Trevor has avoided the melodramatic and the sentimental by a combination of formal rigor and moral tact. Melodrama requires a heavy ladling of suspense; we see, at the beginning, the speed of the train, the innocence of the heroine, the villain’s leer. We know from the beginning that all will come together: the train, the heroine, the villain, in a way that cannot admit of other possibilities. We need only wait. But in Fools of Fortune Trevor creates characters who are doomed not by their natures, but by the nature of Irish history. Willie is a well-intentioned, ordinary boy. He might have had a good life. He might almost not have avenged his family. Only the suicide of his mother pushes him to an act he really wishes to avoid, an act that both his nature and most of his background make him unwilling and unsuited for.

Marianne might not have become obsessed with the honor of the ancient Irish; Imelda might have grown up, profiting by the kindness of those around her; she might never have had to know the details of the stabbing. And Willie might never have come back to Kilneagh. In a subtle plot maneuver, Willie returns to Ireland, ten years before his final homecoming, to attend the funeral of Josephine, his mother’s servant. But, although he is assured that it is safe for him to return, he prefers the consolations of his roses and his villa in Tuscany. He doesn’t come home as the conquering hero who would have had to have some of the vigor of youth for his return to be a triumph. The end of Fools of Fortune is written in the quiet tone that follows shattering violence; nothing can be rebuilt; no life, really, can go on; it can only be lived out.

Trevor the realist turns his tough moral gaze on the romantic situation he has created. Willie is a good boy, but he is a murderer. He has hacked a head from a body he has stabbed in seventeen places. Marianne takes a kind of lustful joy in the vengeance of Irish history; in demanding to be a part of it, she sacrifices her daughter. Yet in the end, something is salvaged. Revenge is over; the cycle of violence will not go on, at least for these people. The cost of the peace they have won, however, is enormous: theirs is the peace of the futureless.

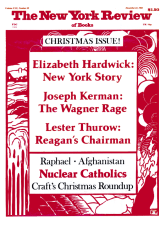

This Issue

December 22, 1983