George Grosz’s autobiography is now appearing in English for the third time—a sign of the continuing interest in his life and work. When the book was first published in 1946, the German text was edited down somewhat and translated by Nola Sachs Dorin. It was decked out with a somewhat random selection of his drawings and paintings (including some in deplorable color), and put out under the title A Little Yes and a Big No. In 1955 Rowohlt of Hamburg published the original German, translating the title and restoring cuts (notably the very funny and none too flattering account of Grosz’s trip to Russia in 1922), reshuffling the drawings and doing without the color. This caused little stir at the time, apart from a long and enthusiastic article in the Times Literary Supplement. The wide recognition of Grosz’s genius as an artist came only in the mid-Sixties (with major exhibitions and the republication of Ecce Homo) and the Seventies (with books on his work by Hans Hess and Beth Irwin Lewis).1 Last year, however, Allison and Busby, subsidized by the Arts Council of Great Britain, published a fresh translation of the autobiography made by Arnold J. Pomerans from the German edition of 1955, shuffling the pictures yet again to make a cramped and meanly laid-out book. And now we have yet another translation, with another title, and another mix of the pictures, with some fresh ones added and slightly more space.

These pictures are something of a distraction, which may be all right if you want to be distracted; and for anyone entirely unfamiliar with Grosz they may well be a revelation. But in none of the book’s four versions are they either aptly chosen or well reproduced. Grosz himself quite early on got into a sloppy habit of using old drawings in contexts they were never meant for, so the chronology and relevance to the text are often confusing; one marvelous drawing of a Nordic sub-Wotan figure smoking a cigar (with the band on) is brutally chopped off at navel-height so that you cannot see the hairy balls which are half its point; moreover, the relations of scale are crazy. In addition, the pictures conflict rather puzzlingly with the author’s frequent protestations that he hates and renounces the work he did before he came to America. It is much better, then, to concentrate on Grosz the witness of his time and treat his memoirs primarily as one of several such accounts by German anti-Nazis of his generation, starting with Ernst Toller’s I Was a German. For these tell us not of the Golden Twenties but of the terrible anxieties, uncertainties, and disappointments that really helped to produce the art of that period; their vivid if still partly unconscious awareness of the cruel and stupid things to come.

It was above all because of this sense of the precariousness of a seemingly advanced civilization that the book made so strong an impression on those who read it just after the Second World War. More recently this has if anything been intensified by the increasing evidence concerning the post-Weimar phase: the rootless and hazardous life which these same people led in exile during the twelve years of Hitler’s Reich. Not only has the Exilliteratur of the writers become an object of academic study, but we have had two very valuable East German series, the one on German theater in exile, the other (in some seven volumes from Reclam) on Kunst und Literatur in antifaschistischen Exil, most interestingly and fully on the exiles in the USSR. There are David Pike’s pioneering account of German Writers in Soviet Exile, James Lyon’s invaluable Bertolt Brecht in America, John Russell Taylor’s more lightweight work on the Hollywood exiles in general, and now the German Historical Institute’s symposium on Exil in Grossbritannien edited by Gerhard Hirschfeld and published by Klett-Cotta. All this makes a new and revealing setting for Grosz’s work and life in the United States and his relationship with exiles elsewhere. For the German cultural diaspora can now start to be seen as a whole: a worldwide network of discouraging choices, which only the toughest artists could productively survive.

Of the remarkable band of mid-European writers, artists, musicians, and theater people who underwent such experiences George Ehrenfried Grosz is perhaps the strangest. Outwardly a copybook example of the large blond German male, brought up in a small Pomeranian garrison town, he was a loyal if sometimes quarrelsome friend, a good family man who could write the most slaveringly erotic letters when separated from his Rubenesque wife, a believer in the traditional virtues of discipline and hard work. Yet when it came to the First World War he twice cracked up from what appears to have been sheer rebellious loathing. “I don’t like talking about it,” he wrote of the first occasion (apparently early in 1915).

Advertisement

I hated being a mere number; and would have done so even if I had been a big number. I was bellowed at till I finally found the courage to bellow back. I defended myself against stinking brutality and stupidity, but I was always in a minority of one. It was literally war to the knife….2

From his letters (which have as yet been published only in German) it appears that the army soon discharged him “for subversive talk against the authority of the State,” only to call him up again at the beginning of 1917. By then, he says, “we already knew that this war was going to end badly,” “we” being the nucleus of what soon became the Berlin Dada movement. Immediately after reporting back he was found semiconscious with his head stuck in the latrine, and was removed to a succession of hospitals. In one of these he attacked a medical sergeant, and was overpowered by half a dozen of his fellow patients.

They did indeed calm me down. But this episode went on burning inside me and could not be extinguished: the way those harmless citizens beat me up, and what splendid fun it was for them. Personally I meant nothing to them. It was just an unconscious principle: we don’t fight back, so why should you?—“Let him have it, stamp on his legs, Karl, on his legs!” After which, no doubt, we peacefully resumed our card-playing, beer-drinking, smoking and swapping of dirty stories.

It was Count Harry Kessler, allegedly, who got Grosz out of the psychiatric hospital at Görden and saved him from being shot as a deserter. And from then on there was an extraordinary split in his life and work. On the one hand there was the out-and-out enemy of German militarism and all its supporters, ranging from the aristocracy and the new industrialists to the social-democratic leaders and the great mass of “harmless citizens” who ultimately would vote for Hitler; here he seemed to be the enemy of German society itself. On the other hand, however, there was the genial companion who asked nothing better than to play cards, drink beer, smoke his pipe, and hear a good story. It was the first of these two Groszes who produced the marvelous pictures of the years 1917–1922, when his eye was penetrating, his draftsmanship exact, his relationship to the modern movement close and constructive, and his social and political criticisms ruthless. It was the first of the two who joined the German Communist party along with other key Dadaists and helped write Die Kunst ist in Gefahr, which remains the most succinct and unvarnished statement of the implications of political art. But it was the second who had in effect to provide for the family and run the shop; and from the moment when he returned from his disillusioning trip to Russia and signed up with Alfred Flechtheim, perhaps the most chic of the new Berlin dealers, it became increasingly difficult for his two personae to work smoothly as a pair.

“I soon got tired of always having to grimace,” he wrote. Hence from about 1923 on his line becomes more and more indecisive as he applies himself to the École de Paris themes and more relaxedly satirical Berlin watercolors which the art market could best absorb. To some extent the second Grosz was still riding on the back of the first, to whose earlier, so much sharper, work his reputation was due. At the same time, while he may by then have lost his positive faith in communism, he was still practically involved in the “Red group” of artists, and went on working for communist publications and theater productions for at least five years more. Morally and artistically this was a somewhat equivocal position, and the ensuing strain is reflected both in the work itself and in the more and more cynical attitudes that he came to adopt. As a result the invitation to go to New York to teach in the summer of 1932 was rather more than the fulfillment of his long-standing obsession with the American legend and the minor trappings of Anglo-Saxon life: of the dreams of that Grosz who in the aftermath of war could try to make a Dadaist of Ben Hecht, and once signed himself to a German patron in improvised (if not improved) English “Herzlichst shake hands with kind regards your old fellow George.” The invitation was not only a lifeline for the anti-Nazi who would have been a sure candidate for arrest in 1933 but also a welcome chance for the desperately self-contradictory artist who needed a change of scene to sort himself out.

Though his wife was at first more hesitant, Grosz in the early 1930s embraced everything about his new country from the Statue of Liberty to the Saturday Evening Post. And by his own account in the autobiography the sorting-out process was so drastic, both politically and artistically, that it sent him lurching back from the extreme left far, far beyond any balanced central position. For the burden of his book is that progressive politics and modern art alike are worthless, a grotesque mistake. Better far then, and financially more rewarding (which in this new philosophy is the same thing), is the spurious naturalistic happiness of the magazine illustrators and the advertising men: the “Have a nice day” approach with its meaningless smile. “Not too German, Mr. Grosz. Not too bitter. You know what we mean, don’t you?” his new patrons are supposed to have said. And indeed he did know just what they meant, and approved of it; it was völlig in Ordnung, or, in other words, okay by him. So he mocks the artist who, Pollock-like, drips paint direct from tin to canvas; and welcomes Hans Sedlmayr’s reactionary book Art in Crisis, which put the cat among the modernist pigeons before Tom Wolfe was ever heard of.

Advertisement

Often these things are amusingly said; the reader may choose to dismiss them as just another aspect of Grosz’s self-protective cynicism. But they can also come distressingly close to what other cultural pessimists were saying between 1933 and the death of Stalin; nor can they always be dismissed as a public pose. For instance there is a letter of May 28, 1945, to his old colleague Erwin Piscator in which he discusses the incompatibility of their views, saying that for his part he hates the masses, hates art and literature, and condemns his own earlier drawings. All he asks of the future is to be able to sunbathe someday on a Mediterranean beach:

But if somebody turns up there and starts gassing away about progress or liberation or culture I shall undo the safety catch on my revolver and promptly shoot.

This remark, whose echoing of words often misattributed to Goering is surely conscious, is not that of a serenely contented man. But does it represent anything remotely like Grosz’s real views, and if not how can we believe any of those which he expresses in his book? No doubt, even in a letter he often gets the bit between his teeth when writing, and lets the momentum of the words and the ideas drive him where it will. He also says at one point that the book is “written American-style,” in other words to be read by people who, he thinks, believe in putting everything in the shop window.

It is in fact anecdotal, with the narrator himself appearing as a slightly fictitious character, rather like the Oldest Member in P.G. Wodehouse’s golfing stories. Some of the anecdotes are vivid and illuminating, like the splendid account of a visit to Villa Shatterhand, the Saxon home of Karl May, a kind of German Zane Grey, who lived in an utterly bourgeois pre-1914 setting. Some show the narrator’s startling political foresight, as when he rudely shouts down Thomas Mann soon after getting to the US and insists that Hitler has come to stay—a prediction incidentally confirmed by his letters and not shared by the German Communist party. Some, like the purely fictional chapter called “A Fairy Story,” are drawn-out and too archly told. Some, on the other hand, like the encounter with Carl Laemmle, the Hollywood tycoon, seem all too credible. But as a statement of what Grosz truly and finally thought about art and life they conceal so many ambiguities as to be largely misleading.

You can see this most immediately from his pictures, whose development does not at all follow the “happy face,” “have a nice day” style he affects to admire. Though we (at any rate I) still need to know more about his American work, it seems on its face to have begun with weak echoes of the Berlin drawings (which were what editors knew and expected), varied by old-masterly pencil studies such as he had already been making in the later 1920s; he then went off in the direction of Alfred Kubin, John Marin, and a depressing, sometimes warravaged type of oil landscape that recalls the First World War pictures of Meidner and Otto Dix. There is a late crop of mildly Dada collages which have often been reproduced, along with many other signs of a wish to pick up threads from the artist’s own past, though generally in a more muddied and indecisive technique and with symbolism in lieu of the old aggressive realism.

Of course creative artists don’t always work in accordance with their own principles and preferences—i.e., paint (or compose, or write) the sort of works that they themselves best admire and enjoy. The creative handwriting is apt willy-nilly to go its own way. But there are also many signs, particularly in Grosz’s correspondence, that he remained extremely fond of such earlier paintings as Deutschland, ein Wintermärchen and the one dedicated to Oskar Panizza, and was not exactly ashamed of his drawings’ place in twentieth-century history. He was certainly anxious that those drawings—and of course his few years as a faithful communist—should not be a hazard to his family, first when leaving Germany, then in applying for US citizenship, and later in the eyes of the various anticommunist investigators. But at no stage did he, or perhaps could he, draw in the style of Norman Rockwell and the Saturday Evening Post.

Nor for that matter did he make a clean cut where his 1920s friendships were concerned. Here too his letters are most interesting, showing him as almost unforgivably quarrelsome and insulting when drunk, and quick to resent any sign of condescension by those better off than himself; then perhaps revising his attitude after another encounter and deciding to resume his old relationship after all. “Perhaps what I liked in him was a piece of shared past rather than a piece of the future,” he wrote in 1949 of his old communist friend and former publisher Wieland Herzfelde, with whom he never broke.

Brecht, again, he continued to like for his company and his sense of humor, though there were some hiccups in their friendship and Grosz could write contemptuously of the poet’s didactic attitude and pro-Russian views. Where he did make a break, as with the ex-Dadaist Walter Mehring, it seems to have been for personal rather than political motives. But there were not many such instances, and more often we find the characteristic ambiguity: sour mockery when discussing the man on paper, warm affection when meeting him face to face. Even his old teacher at the Dresden Academy—that Professor Richard Mueller whom the autobiography depicts as tormenting the models and brushing aside Nolde and Van Gogh as “shit-artists”—was sent food parcels after the Second World War, at a time when the Groszes themselves were finding it none too easy to manage. Like Brecht, Grosz was as capable of damning remarks as of generous acts; the one never precluded the other.

Whatever tensions such contradictory attitudes built up in him, they were quite clearly not resolved by becoming an American. “Pessimism and the most horrible depressions plagued me from an early age,” he once told Herzfelde, and to one of his first patrons he wrote in 1949 that even in the relative peace of Cape Cod he was almost always “ein gehaunteter Mensch.”

One answer was to assume the attitude of complete self-abnegating cynicism that so permeates his book: for instance the tongue-in-cheek account of the private lessons that he gave to the Baltimore hostess Mrs. Garrett, where he “adopted the manners and courtesy of a tutor at court.” But clearly such cynicism was not enough, and in fact it may very well have made the internal stresses still more unbearable. The other answer, then, only hinted at in the autobiography with its reference to “a few planter’s punches,” was to drink. The problem that this came to represent emerges at various points in the letters, most tellingly perhaps in one of 1953 to his brother-in-law where Grosz says that he has become a total abstainer, not least because his work was suffering from such escapist boozing. For unlike Pascin and Toulouse-Lautrec, “I could never work when drunk or half-drunk”—something that would certainly explain his hand’s increasing lack of sureness. His good resolution evidently was not kept, and in 1957 he could admit some truth in Richard Huelsenbeck’s diagnosis that he was slowly drinking himself to death. But perhaps nothing is quite so devastating as a letter of 1947 to a fellow drinker where he claimed to be drinking to kill the “moralist” in himself, along with his humanism and sense of justice. The wonder is that he could still hold up as well as he did.

It is a great pity that Grosz’s deeply self-destructive style of writing, with its drive toward catastrophe—the collapse of himself, of his art, of the civilized world—so easily translates into the merely cute. This is not peculiar to Nora Hodges’s generally readable version, for the same trouble affected its two predecessors and surely reflects basic differences in the inbuilt “humor” of the English and German languages; it is bad when our vaunted sense of humor interferes with our ability to sense the tragic. Nonetheless Ms. Hodges could have done a good deal more to get the flavor of Grosz’s remarks. Too many of his key phrases come out of the mangle a bit crumpled: “Wie denke ich morgen?” for instance, meaning literally and ambiguously “How shall I think tomorrow?” is simplified as “What will I believe tomorrow?” which is not at all the same thing. “Dada über Alles,” another early slogan, emerges as “Dada above all,” thus missing the intent to parody the German national anthem. The same with other characteristic dicta.3

In the end there is not all that much to choose between the three English-language versions. None of them is particularly well translated or produced, and all three contain many impossibly minuscule reproductions. The old Dial Press edition of 1946 has a well-designed binding, large pages, good-sized type, and ample leading between the lines, but omits an essential chapter. Last year’s version published by Allison and Busby is the worst designed and reproduced, but the fullest and most accurately translated; it is also the only one with an index. The current republication reads more easily because the leading and margins are more generous; moreover, it includes a number of previously unpublished drawings and reproduces them better, though often on too small a scale. However, it unexplainedly omits the passages concerning Edward James and Garnet Lake from the penultimate chapter, and its translation is, as we have seen, not all that reliable.

None of the three is likely to satisfy the reader seriously interested in Grosz, who is still waiting not only for a worthy rendering of this extraordinary book but for an English edition of the letters, a translation of the early poems (which deserve to be much more widely known), and a selection from Die Kunst ist in Gefahr and other miscellaneous writings. Above all we need a well-reproduced, chronologically arranged representative selection of the graphic work, which will long be seen as Grosz’s great achievement. Ten years ago Herbert Knust and the Busch-Reisinger Museum showed the way with their informative, economical catalog Theatrical Drawings and Water-colors by George Grosz. No publication in English has come up to this since.

This Issue

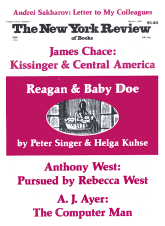

March 1, 1984

-

1

Hans Hess, George Grosz (Macmillan, 1974); Beth Irwin Lewis, George Grosz: Art and Politics in the Weimar Republic (University of Wisconsin Press, 1971).

↩ -

2

Translations in the text are by the reviewer.

↩ -

3

There are also instances of mere bad translation—the kind one notices not by deliberate nit-picking but by being puzzled about what the translator means. So Schwitter’s Merzkunst becomes unintelligible when rendered as “art of the rejected”; Brecht’s Lehrdrama as “teaching dramatics”; Seeckt’s Schwarze Reichswehr as “the Black National Defense.” There are common howlers—”genial” for “genial” (meaning “brilliant”), “character” for “Charakter” (meaning “moral fiber”). There are incomprehensible changes: where Grosz has Brecht arrive with a “proletarian” who betrays his Berlin slum origin by giving Grosz a KPD prospectus, Ms. Hodges makes this (unknown) man a “hoodlum” and has Brecht giving the prospectus.

↩