The rising that took place in St. Petersburg on December 14, 1825, is one of history’s prime examples of how not to make a revolution. The aristocratic army officers who predominated among the conspirators could not agree on their political aims. The leaders included monarchists, republicans, and a noted Romantic poet whose political concepts were vague in the extreme. Nor, over the decade of their society’s existence, had the Decembrists (as they subsequently came to be known) given much thought to tactics, strategy, or the choice of leaders. The short space between the decision to act and the rising itself (precipitated by the sudden death of Alexander I and the confusion surrounding the succession) did not serve to concentrate their minds. The plan was that the troops under their command, assembled on Senate Square to take the oath of loyalty to the new czar, would refuse, sparking off a general revolt. But on the day, confusion reigned. The officer selected as leader of the revolt and future dictator of Russia wandered aimlessly around the city and finally sought refuge with a cousin in the Austrian embassy, and none of his comrades proved any more decisive. The bewildered troops stood patiently on the square until they were mown down by a battalion loyal to the czar, while most of the conspirators returned home to await arrest.

The tragicomedy on Senate Square may affect the historian’s assessment of the Decembrists, but it did nothing to diminish the veneration in which they were held by future generations of the Russian intelligentsia. For them, the Decembrists’ precise political aims were of minor significance; what mattered was their moral opposition to autocracy and serfdom. As their depositions, recorded during the long official investigation, revealed, they had formed from a variety of sources (including classical authors, the French Encyclopédistes, European Romanticism, and their own experience of Europe during the Napoleonic campaigns after 1812) an ideal of freedom and dignity incompatible with the status quo in their country.

By his vindictive response (five of the leaders were hanged, and 121 men sentenced to exile with hard labor in Siberia) Nicolas I intended to obliterate the memory of the Decembrists. He succeeded only in creating martyrs and fostering a legend which grew over the next three decades with each new report of the exiles’ activities: their mutual self-help organization, in which goods and funds were distributed according to individual need, their researches into agriculture and ethnography, and their work in education and medicine, all applied for the benefit of the local population. The Decembrists’ considerable achievements in the practical application of their liberal and humanist ideals, recorded in the memoirs that many of them published after they were amnestied in 1856, have generated a vast and still growing academic industry. In nineteenth-century Russia they served a more practical function: they provided the nascent revolutionary tradition with models of moral nobility and selflessness.

These models were of both sexes. Describing in his memoirs the panic that took hold of Russian society after the uncovering of the Decembrist plot, Alexander Herzen remarked that only one section of society displayed courage and dignity: ‘except women, no one dared to show sympathy or to utter a word about relations or friends whose hands they had shaken only the day before the police had carried them off by night.” In a society where the values of religion, patriotism, and obedience to the sovereign formed one indissoluble whole, the moral independence of such women was remarkable. Even more so was the courage of those wives who resisted the pressure exerted on them by their families, the bureaucracy, and the czar himself to cut themselves adrift from their convicted husbands. (In the case of the Decembrist wives, the Orthodox Church was accommodatingly prepared to lift its opposition to divorce.) Nicholas decreed that any wife who insisted on joining her husband in exile would, as the wife of a “state criminal,” be permanently deprived of her noble status and her property, and separated from her existing children. All children born to her in exile would be classified as serfs, the property of the state. If, undeterred by these sanctions, any woman attempted the extremely hazardous journey across the Urals to the Siberian prisons, officials along the way were instructed to use all means that bureacratic imagination could devise to prevent them from completing their journey.

The dozen or so wives and fiancées who overcame these obstacles to join their men in Siberia were not political radicals. No woman took part in the Decembrist conspiracy, and there is no evidence that any of the conspirators’ wives knew of it before it was uncovered. Most were the daughters of families who owed their noble status and fortunes to centuries of state service. Their sacrifice was motivated to a large extent by the submissive loyalty that state and church regarded as the supreme virtue of wives; but equally important was their desire to emulate the generosity of motive that the husbands revealed during the investigation of the conspiracy.

Advertisement

In their capacity for sustained self-abnegation in the name of instinctively held moral imperatives, the Decembrist wives were the acknowledged precursors of generations of women of the Russian intelligentsia, whose prominence in the Russian revolutionary movement (a phenomenon without parallel elsewhere in Europe) has been the subject of a number of studies in recent years.1 Stimulated by the feminist movement, these studies have increasingly concentrated on the social forces and value systems that prompted such women to challenge conventional social roles. Christine Sutherland’s biography of Maria Volkonsky, who was arguably the most remarkable of the Decembrist wives, can be seen as a contribution to a fascinating part of Russian social history which is only beginning to be explored.

Maria Volkonsky was the exceptionally attractive and talented child of a wealthy aristocratic family close to the Imperial court (her father, General Raevsky, was a famous military hero). She was well educated at home in music, languages, and literature and combined an allegiance to traditional family and religious values with an unfocused idealism fostered by the Romantic writers. She was addicted to literature and poetry from an early age, and when she was fourteen the young poet Pushkin became her devoted friend. In January 1825, at the age of nineteen, She made a brilliant marriage to Prince Sergei Volkonsky, heir to one of Russia’s oldest aristocratic families and, as was revealed at the end of that year, a leading Decembrist.

At first Maria saw her husband’s actions as treason, but an imagination fed on Schiller, Byron, and Walter Scott could not fail to be roused by the details that subsequently leaked out of the Decembrists’ sacrifice for the cause of liberty. To a great extent, it was Romantic exaltation that sustained her in her year-long battle for permission to follow Sergei to Siberia and that reconciled her to the prospect of parting with a baby son.

In January 1827, two carriages set out on the dangerous month-long journey across the Urals and over the frozen Lake Baikal to the ore mines of Nerchinsk. The first contained Maria and her maid, the second her luggage, which included a piano. Her first act, on being led into her husband’s cell, was to kneel and kiss his chains.

Intoxication with the role of romantic heroine helped to carry Maria through the greatest crisis in her life, but much more solid qualities of endurance and initiative sustained her through the thirty monotonous years that followed. When the Decembrists were brought together in a single prison, she emerged as a leader among the wives. Writing quantities of letters each week, she served as a channel of communication for the prisoners, who were forbidden to correspond with their relatives in Russia. Over the years, with dogged persistence and a fair measure of success, she threatened, bribed, and cajoled the authorities to secure greater humanity and, whenever possible, a bending of the rules, in their treatment of the prisoners. When in the mid-1830s the Decembrists began to disperse to their places of exile, she maintained contact with those whose relatives had forgotten them, and channeled funds to them.

Her philanthropic energies found a wider field for expression when Nikolai Muraviev-Amursky, an open admirer of the Decembrists, became governor of eastern Siberia. In its capital, Irkutsk, where the Volkonskys were permitted to reside in 1844, Maria, supported by the governor’s personal patronage and friendship, set to work transforming the city’s foundling hospital into a model for the region, improving the level of public education, raising funds for the building of a theater and concert hall, and supervising their construction. She was affectionately known as “our Princess” by the local population and when after the amnesty she left Irkutsk to spend the last seven years of her life in Russia, the street where she had lived was given her name.

As Christine Sutherland remarks in her conclusion, the achievement of Maria Volkonsky and her companions was a triumph of love, courage, and humanity over the Russian bureaucratic system. They were not impelled by political motives and were not conscious rebels. Their first loyalty was to their husbands; nevertheless, later generations of Russian women who felt that their duty extended to all the victims of autocracy—revolutionaries such as Vera Figner, Vera Zasulich, and Sofya Perovsky, who were to become legendary for their moral fervor and self-denial—were to see the Decembrist wives as models.

But those who look in Sutherland’s book for clues about the complex psychology of these later heroines will be disappointed. The book is best on anecdote and visual detail: Maria’s childhood in the Ukraine, her journey to Siberia, and the life of the exiles there are skillfully collated from the many published memoir sources. All the scenes of the movie that begs to be made are here: unfortunately, so are the central characters. Variously labeled as charming, distinguished, glamorous, dashing, and dazzling, they are the aristocratic stereotypes of the screenwriter rather than individuals with inner lives of any complexity. Ms. Sutherland’s emphasis on the idealized façades of aristocracy does, however, serve the function of reminding us that the Decembrists and their wives, even in the isolation of the Nerchinsk mines, were never helpless outcasts. Their existence was considerably lightened by the material and moral support of the privileged society they had left behind.

Advertisement

In theory, they were stripped of all the privileges of their caste. In practice they remained part of a network of patronage whose influence extended into the bosom of the Imperial family, and which helped to ensure that the punishment devised by Nicholas was never carried out in its full harshness. The hard labor to which the men were sentenced was for the most part no more taxing than strenuous physical exercise. To the common criminals who lived alongside but not with them, they were “their Excellencies,” and their wives received the respect accorded to the ranks of which they had been deprived. The rules notwithstanding, books, periodicals, money, and luxuries flowed to the prisoners from their wealthy families. Nicholas’s edict on the status of children born in exile was not carried out to the letter. The son born to Maria in Siberia was launched on a career in the civil service under Muraviev’s patronage; her daughter settled in Moscow after marrying one of Muraviev’s protégés. The Petersburg authorities were sent regular reports about the prisoners’ health, and when Maria petitioned the chief of police (an old schoolmate of Sergei’s) to allow windows to be built in the Decembrists’ cells, they were built. His successor granted Maria’s request for permission to settle in Irkutsk in order to secure the best available education for her children.

Even more important for the exiles’ morale was the sympathy and admiration they encountered from people at all levels of society. Before 1855 instances of this increased in proportion to the distance from St. Petersburg, but after the accession of a Tsar who promised to end serfdom and institute an era of reforms, liberal ideas became fashionable even in the bureaucracy, and those who had suffered for them were treated as heroes when they returned to Russia. Thirty years after Maria Volkonsky had brought shame on her family by following her disgraced husband, “Decembrist bracelets,” modeled on those the exiles had had made for their wives from their chains, were the rage among society women. To marry the descendant of a Decembrist was said to be a greater distinction than to marry a Romanov.

Maria Volkonsky could die in the knowledge that her sacrifice had helped to awaken the conscience of Russian society and contributed to an epoch of profound change. The same was true of the women revolutionaries of the second half of the century, whose behavior during their trials earned them the admiration and sympathy of many who did not support their political goals. The fact that they had this consolation does not diminish their sacrifice; but it should be remembered that even more heroic qualities of love and endurance were demanded of later generations. The tradition begun by the Decembrist women did not end with the legendary women whose names appear in every study of the Russian revolutionary movement; it continued with the anonymous outcasts to whom Anna Akhmatova dedicated her Requiem, the women who, at the height of Stalin’s terror, stood with her in an endless queue, month after month, before the closed gates of a Leningrad prison, hoping to hand in a parcel or to hear news of a vanished husband or son.

I should like to call you all by name,

But they have lost the lists.2

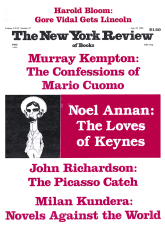

This Issue

July 19, 1984